Team:Valencia/Project/Modeling

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Oxidative phosphorylation model coupled with thermogenine expression

Our project consists of implementing a controlled heating system inside Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In order to obtain this we are going to use a mitocondrial membrane protein known as thermogenin used by mamalians cells to increase their temperature.

The working principle of thermogenin is based on the respiratory chain. The way in which thermogenin increases the temperature of the system can be described approximately as follows: It produces a hole on the mitocondrial membrane which makes difficult the production of a proton gradient in the membrane. The release of the mitocondrial proton gradient increases the temperature.

In order to describe the system three complementary models have been developed :

- Black box model of the temperature increase by the thermogenin.

- Detailed model of the respiratory electron transport chain.

- Regulatory model of the thermogenin expresion.

Theoretical evaluation of the idea

To evaluate the reliability of the idea we are going to estimate the maximal attainable temperature (obviously, the minimal temperature value is the corresponding to the culture conditions). This means to estimate the maximum heat production. The maximal temperature can be determined by supposing that the proton motive force is used solely in heat production mediated by thermogenine. The following calculations were made taking into account this assumption.

In order to estimate the potential temperature increase produced by this organism we argue in the following way:

- Glucose consume of a culture of our yeast is in the order of 1 g/h (Gonçalvez et al.) .

- Considering that each molecule of glucose could give us in the order of 30 ATP molecules in the respiratory transport chain.

- Taking into account that each molecule of ATP generated throught ATPase requires about 4 protons.

- Assuming that the free energy associated to a single proton being dissipated through the ATPase is 20 Kj/mol.

From all these hypothesis we have a net energy production of the system of 5 J/s.

If we apply this energy to our culture and we assume that our growth media is equivalent to water. We obtain that this energy will produce a temperature increase of 0.01 K/s. Therefore the increase of the tempeature in one hour can be of 30 degrees!!!

Nevertheless, in this process several assumptions have been made that should be considered:

- There is no heat losses to the ambient.

- Glucose is metabolized only through the respiratory transport. (this is not true in fact other pathway like fermentation can be important).

- Atpase is completely inactive and all the dissipated protons produce heat. (We did not block this enzyme and the system requires to produce atp to live).

- If we increase the temperature too much probably the glucose uptake data and other estimations performed here will be not applicable and the heat production of the system will stop.

Even all these drawback in the heat production, as the system has a great potential of producing heat, we hope to be able to detect an effect of the UCP in the temperature of the system :-)

Black box model of temperature increase produced by thermogenin

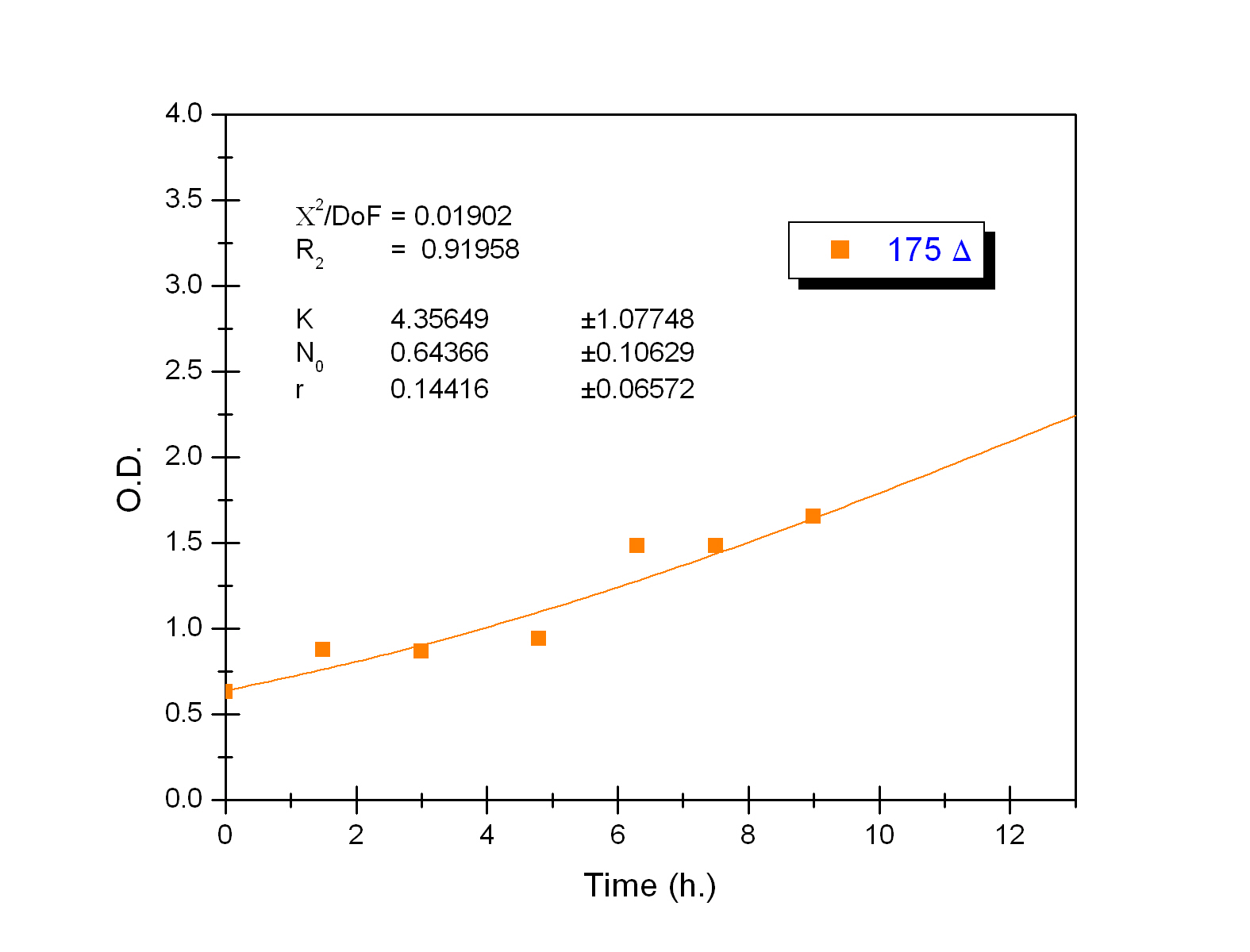

The black box model simulates the temperature evolution of the system as a function of the growth rate, galactose concentration and thermogenin expresion. We assume that our system can be reproduced by the following system of equations:

where:

- first equation: Growth of the culture: logistic growth of the different mutants used in our experiments.

- second equation: Galactose evolution: Galactose is the metabolite which induces the thermogenin expresion.

- third equation: Thermogenin concentration level.

- Fourth equation: Temperature evolution. the first term of the equation represents the losses to the ambient of the calorimeter and the second one the temperature increase as a consequence of the thermogenin expresion.

Growth equation

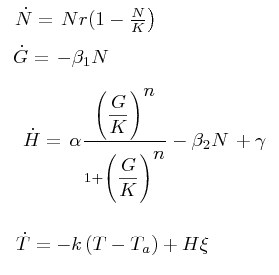

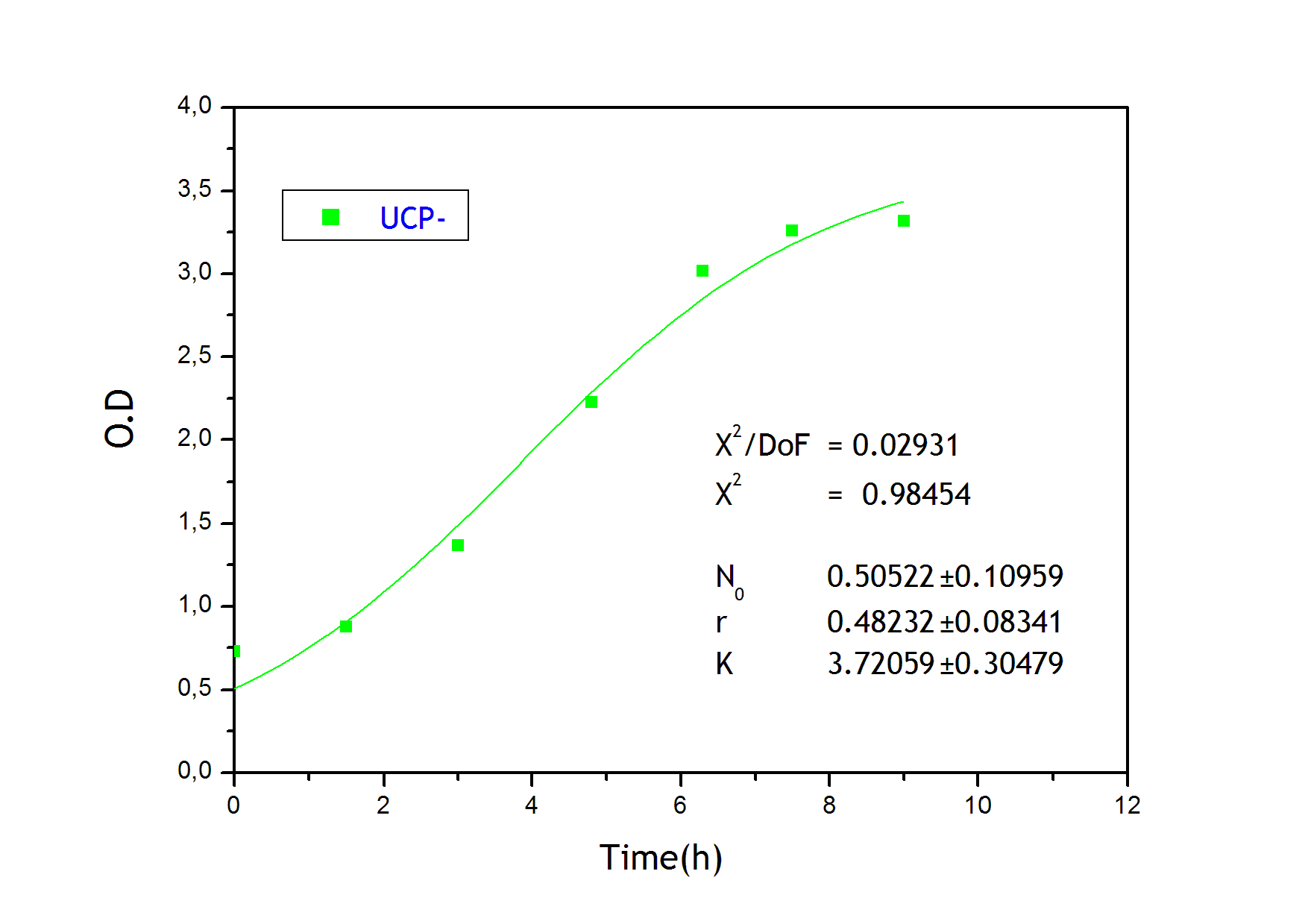

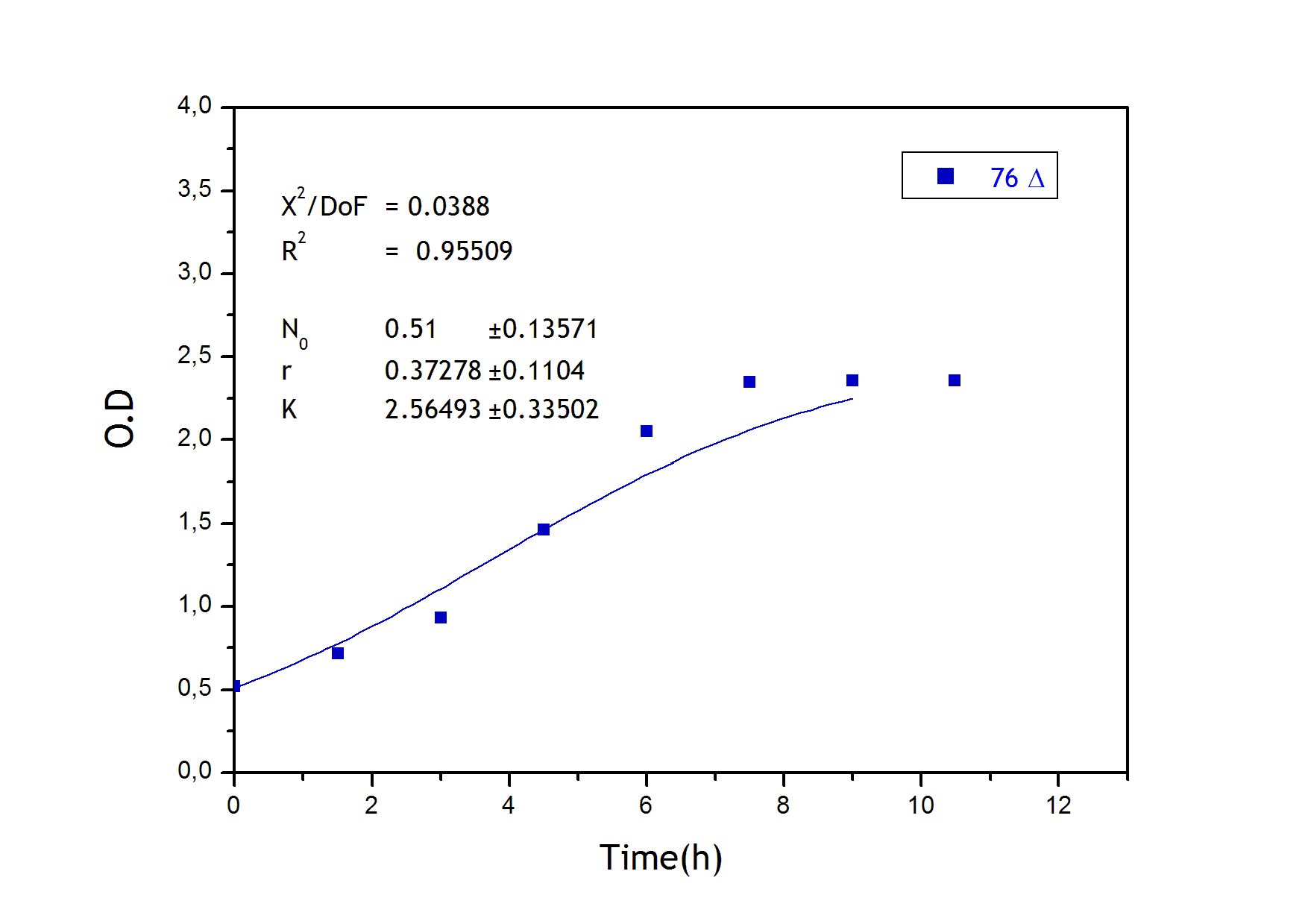

To obtain the following data we grew all our strains inside the LCC at 270 r.p.m in S.P medium with galactose induction. We fitted the curves to the logistic growth equation using the non-linear curve fitting tool from OriginPro program.

Where K stands for the carrying capacity and r for the grow rate.

The fitting is statistically significant at the 5% level, with good R2 , thus the logistic curve explains well the data. The expression of non functional UCP in the positive control affect slightly its growth in comparison with the negative control. On the other hand, both mutants were affected by the expression of functional UCP reducing their carrying capacity regarding the controls. More specifically, 175 \delta growth rate is slowed down, coherent with the glycine mutation that enhances UCP function. We conclude that th functional UCP is possitively expressed in the mutants.

Temperature equation

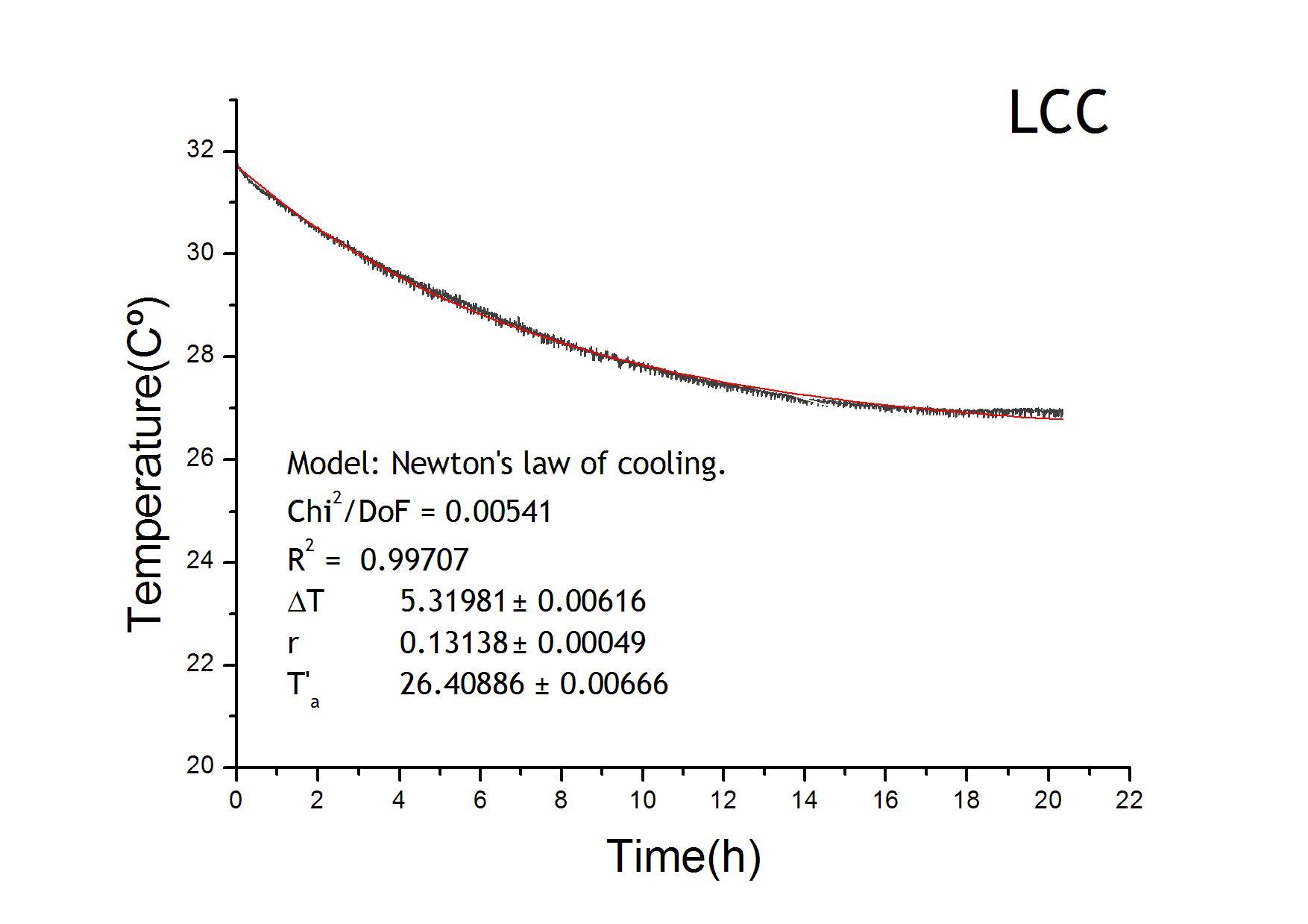

The temperature equation has a heat loss term which follows Newton’s law of cooling. We adjusted the results from the LCC characterization in order to get the parameters for the loss term of the temperature evolution equation. Environment temperature remained constant at 22ºC. From the figure it is also tested that the behaviour of the four calorimeters are equivalent.

From the previous experiments the costants

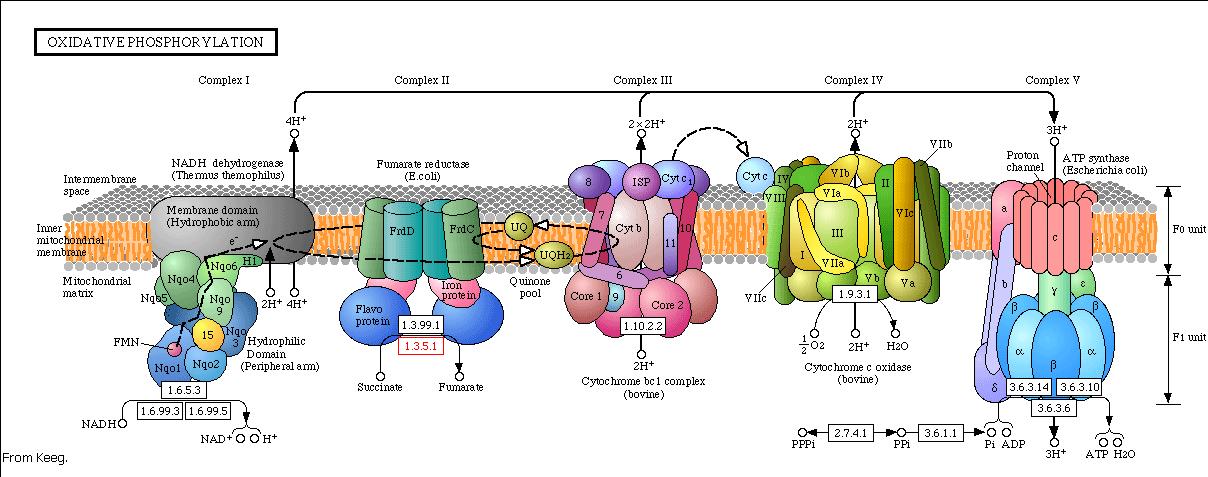

Modeling the oxidative phosphorylation pathway

The energy, in form of ATP, necessary for all the cellular processes, is acquired mainly by the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. This pathway is wide-spread through the tree of life because it is a highly efficient way of releasing energy, compared to alternative fermentation processes such as anaerobic glycolysis. In eukaryotic organisms, the reaction takes place in the mitochondria where the electron transport chain catalyzes the electron flow from NADH and FADH 2 to oxygen (becoming reduced to water). This exergonic reaction is coupled with the proton pumping from the matrix through the inner mitochondrial membrane, which generates an electroosmotic gradient used for ATP synthesis. This mechanism is called chemiosmosis, proposed in 1961 by Peter Mitchell.

|

With this model we want to evaluate the effects of the UCP1 in the ATP synthesis. We will take into account general issues about the electron transport chain as well as the particularities of our yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We will have to consider the fermentative pathways presents for further applicability of the model.

Complex I

The first step of the respiratory chain is the oxidation of NADH through complex I (also known as NADH dehydrogenase). This multimeric complex is constituted by 43 different proteins, including a flavoprotein and six iron-sulfur clusters as prosthetic groups. The reactions catalyzed by this complex are coupled, so the exergonic transfer of electrons to quinone promotes the endergonic proton pumping from the matrix to the intermembrane space.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacks complex I (Vries et al 1988), but oxidizes NADH with the help two NADH dehydrogenases structurally different from complex I. Complex I is unable to use the citosolic pool of NADH (as is faced to the matrix and NADH does not diffuse through the inner membrane), but NADH dehydrogenases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae use both pools. So there are two enzymes: one uses the external NADH while the other the internal. Both enzymes presence depends on culture growth conditions and phase.

From a structural point of view, these enzymes are much simpler than complex I. This feature is related to the fact that these NADH dehydrogenases transfer electrons without any translocation of protons across the membrane. Because of this reason, we will have two pools of NADH in our model as well as two different equation for NADH dehydrogenation.

The internal NADH dehydrogenase is a single subunit enzyme coded by nuclear DNA. It has FAD as prosthetic group, but lacks iron-sulfur clusters. Unlike complex I, which is a one electron reacting enzyme, internal NADH dehydrogenase is a two electron reacting enzyme, preventing the formation of ROS.

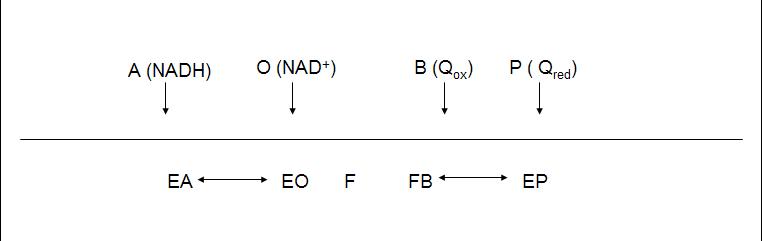

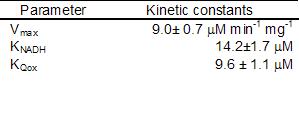

The enzyme follows a bi bi ping pong mechanism.The kinetic data was obtained with the artificial acceptor DCPIP instead of quinone (Velázquez et al 2001), nevertheless we will take its Michaelis constant as a reference for quinone real value.

The diagram shows the reaction, where NADH binds to the enzyme and transfers two electrons to the prosthetic group FAD. After the reduction of the enzyme (F) NAD+ is released and F recovers its redox state by reducing quinone.

The rate equation for the internal NADH dehydrogenase:

The external NADH dehydrogenase must follow the same kinetic scheme. We could not find data for the Michaelis constant for Q as well as for Vmax, so we used the internal dehydrogenase values as an estimation.

Modeling the control system

Our device is able to increase the environment temperature. We would like to control the effect of our system so as to keep the surroundings near a desired temperature. With these features the final biological construction would resemble a heating system with a thermostat. In order to achieve it we will need a way of sensing temperature. We have designed a system based on cold shock proteins. By modifying the strength of the promoter of our constructions we will tune the setpoint temperature to the desired value.

References

Abrams, A.; Smith, J.B. (1974); The Enzymes, 3rd Ed. (Boyer, P.D., ed.) Bacterial membrane ATPase 10, 395-429.

Velázquez I.; Pardo J.P. (2001); Kinetic Characterization of the Rotenon-Insensitive Internal NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase of Mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Archives of Biochemistry and Byophysics.Vol 389 pp 7-14

Vries S.; Grivell L.A: (1988) ; Purification and characterization of a rotenone-insensitive NADH:Q6 oxidoreductase from mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.European Journal of Biochemistry. 176: 377-384.

"

"