Team:ETH Zurich/Wetlab/Switch Circuit

From 2008.igem.org

|

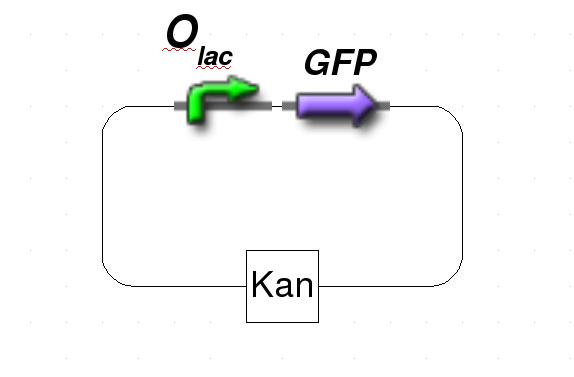

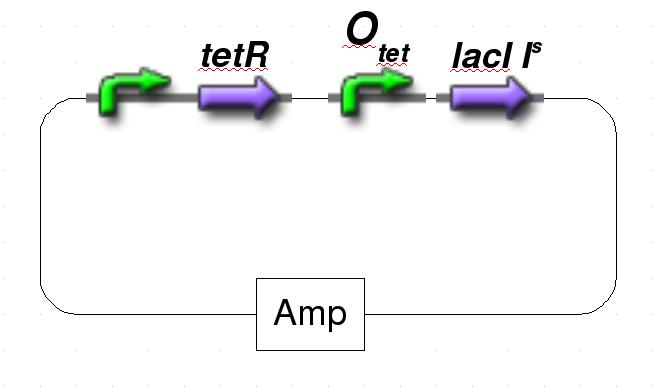

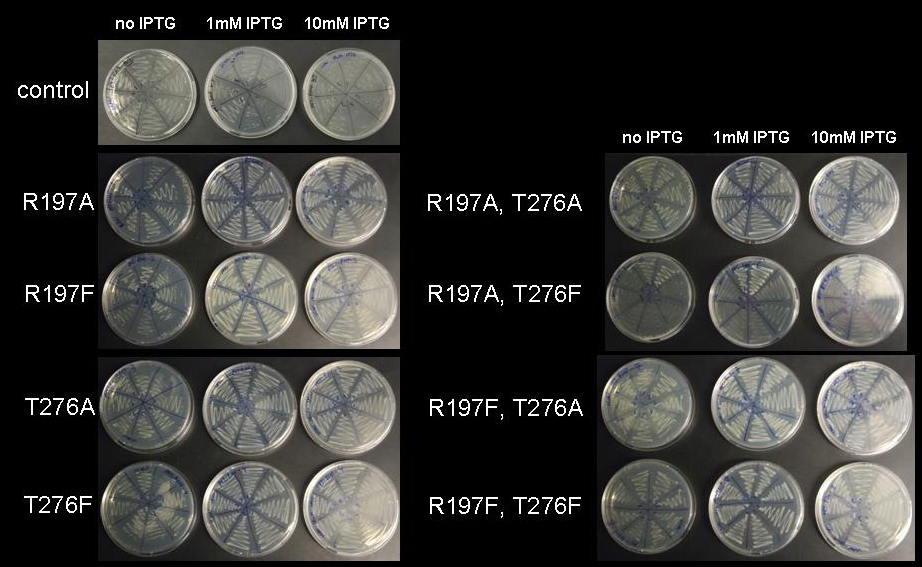

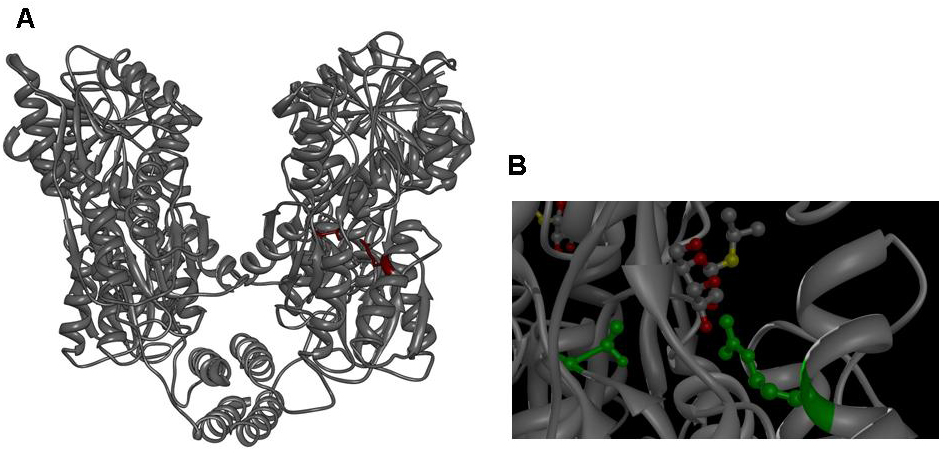

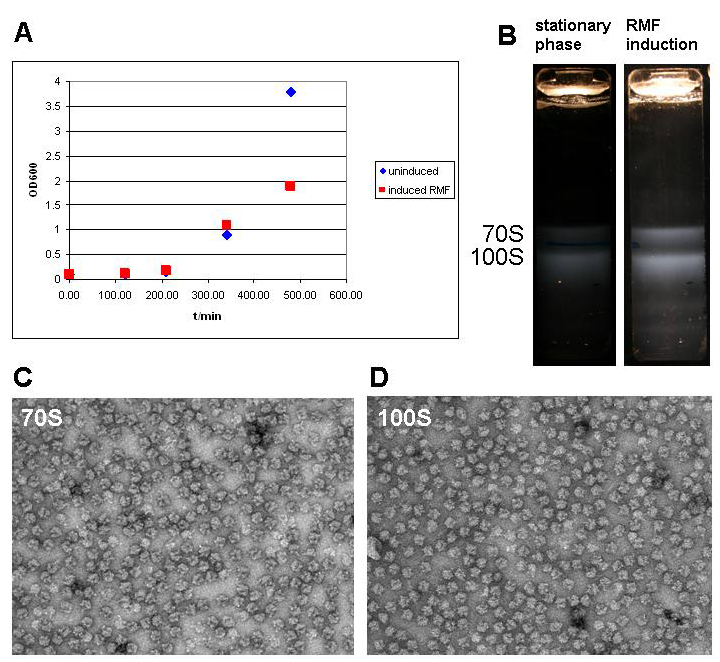

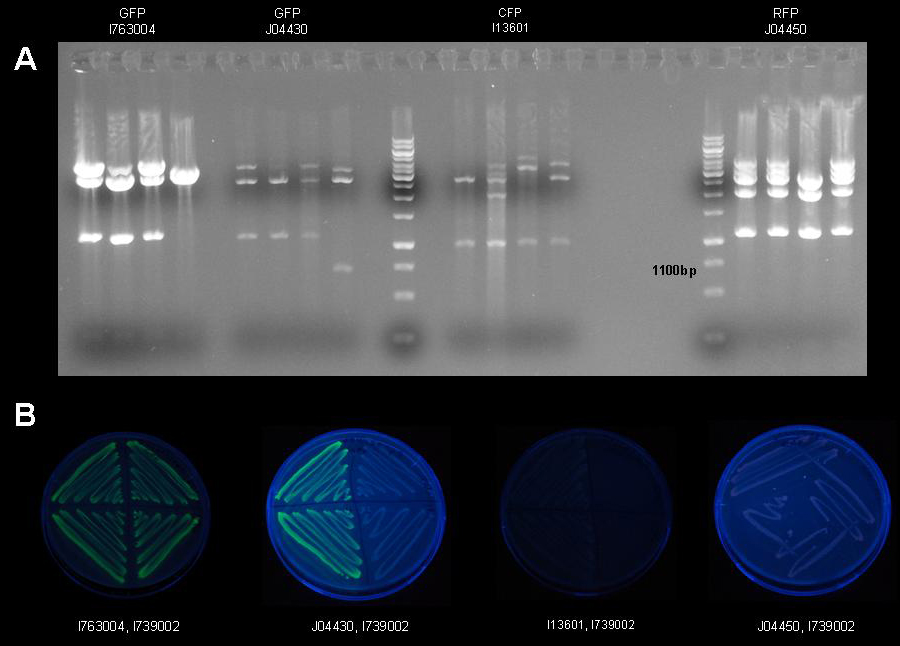

Switch CircuitOverviewIntroductionMany biological applications require a pulse mechanism that enables on the one hand a fast production and high accumulation of specific protein at one time and on the other hand a fast elimination of this protein after a period of time has passed. Pulse generators that turn on and off protein production are essential parts of engineered genetic circuits and allow the synthetic biologist to control timed expression of the protein of interest. It is obvious that a robust pulse generator is essential for our approach to the minimal genome, since we are planning to express a restriction enzyme in a brief pulse that is short enough to cause sublethal damage to the cells’ genome but on the other hand long enough to allow the restriction enzyme to leave a lasting impression on the genome. It is obvious that the ideal duration of restriction enzyme expression pulse has to be determined empirically by inducing expression of the restriction enzyme for different durations and at the same time monitoring the survival rate of the cells. Pulse generators based on a feed-forward motif have been described previously and are considered superior since they require only one inducer and automatically terminate expression of the protein after a certain time has passed, however, they are parameter-sensitive and difficult to construct. For our approach this type of pulse generator is of little use, since change of the duration of the pulse requires extensive modification to the constructs holding the pulse generator. We have therefore devised a very simple, but effective pulse generator, which turns on protein expression upon induction with IPTG or lactose and turns off protein expression by addition of tetracycline. This pulse generator functions as a switch and allows the synthetic biologist to turn expression of a gene on and off at will for durations specified by the experimenter rather that by parameters of the construct. Our pulse generator acts on promoters, which contain the lac repressor binding motif. Those promoters are used almost universally for recombinant protein expression such as in the [http://www.merckbiosciences.com/g.asp?f=NVG/pETtable.html pET vectors] of the T7 expression system (1-3) and can be subjected to control by our pulse generator without further modification. General layout of the pulse generatorThe basic idea for the pulse generator was to use the lac repressor to control the start of expression and then use a second protein under control of a different promoter, which in turn would shut down expression by binding tightly to a motif contained inside the lac repressor binding site after induction of it’s promoter with a second inducer. While there are numerous proteins, which bind tightly to specific DNA sequences and while it is even possible to engineer these proteins to bind to a DNA sequence of choice (4-7), we decided to use the IS lac repressor mutant, which binds to the lac repressor binding site like the wild type but does not lose affinity for the binding site in the presence of IPTG or lactose (8). Since expression of the mutant lacI has to be tightly controlled to avoid repression of lac-controlled gene expression despite presence of inducer, it was decided to put it under control of the tet repressor (9, 10). The pulse generator consists of two parts, a constitutively active TetR generator (unlike in the case of the lac repressor, which is expressed under control of its own promoter, E. coli does not produce tet repressor) and a lacI IS mutant gene under the control of the tet repressor. The constitutively active TetR generator supplies the TetR repressor, which binds to the repressor binding site in front of the lacI IS gene and releases the binding site upon induction with tetracycline. Induction with tetracycline leads to expression of the lacI IS mutant and this protein binds to the lac repressor binding site in front of the activated gene of interest despite presence of lactose or IPTG activator. With this system, IPTG induction initiates expression of the protein of interest while tetracycline induction rapidly terminates the expression of the protein. Design of the lacI IS mutantsSince the discovery of the lac repressor over 40 years ago (11), it has been subjected to extensive genetic studies, which have identified numerous mutants with different defects in activity (8, 12-25). The determination of the atomic structure of the lac repressor by itself (26) and in complex with IPTG (27) by x-ray crystallography furthered the understanding of repressor activity on the molecular level and allowed to assign mutations to different functional regions of the molecule. Mutations in several regions of the lac repressor can lead to the lacI IS phenotype: Mutations at the N-terminal domain of the core, mutations of the dimerization interface and mutations of the residues, which establish the IPTG contact. We decided to create lacI IS mutants by mutation of two residues, which form part of the IPTG binding site: R197 and T276.  Figure 3: A Lac repressor tetramer, residues R197 and T276 are shown in red. B IPTG bound to the inducer binding site of the lac repressor, residues R197 and T276 are shown in green. Molecular graphics was generated from coordinate set [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore.do?structureId=1LBH 1lbh] (27) using [http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ UCSF Chimera]. We are not aware of quantitative studies that detail the strength of repression with respect to different mutations (in one genetic study (8) a repressor strength of >200 has been determined for numerous IS mutants including mutations of R197 and T276) or with respect to the combination between different mutations and we therefore set out to replace either residue with alanine or phenylalanine and in addition we constructed double mutants with all combinations of the two mutations. Our set of lacI IS mutations therefore comprises eight different mutants: R197A; R197F; T276A; T276F; R197A T276A; R197A T276F; R197F T276A; R197F T276F. In order to get an impression of the efficiency of repression by the LacI IS mutants generated, we performed a genetic experiment linking the viability of cells to the repressor strength of the LacI IS mutants in question. Estimate of LacI IS repressor strengthIn order to characterize the lacI IS mutants generated – especially with respect to the double mutants – we performed a series of simple genetic experiments, which would allow us to identify promising mutations and reject mutations that allow significant induction at IPTG concentrations regularly used for induction (usually between 0.1mM and 1mM). Ideally, the experiment would link repression of a lac inducible gene to a marked change in cell growth or morphology. We decided to use ribosome modulation factor (RMF) in one series of experiments and fluorescent proteins in another series as an indicator of lac repressor activity. Ribosome modulation factor (RMF) experimentsRibosome modulation factor (RMF, Uniprot [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P0AFW2 P0AFW2]) is a small protein, which is found in many bacteria. RMF is expressed when bacterial cultures reach the stationary phase (28, 29) and terminates protein synthesis efficiently by binding to ribosomes. Biochemical studies have shown that expression of RMF leads to dimerization of ribosomes (the bacterial 70S ribosomes form a complex with a sedimentation velocity of 100S) and chemical crosslinking studies elucidated that RMF binds to the peptidyl transferase center (30, 31). Since expression of RMF reversibly terminates protein expression and thereby stops bacterial growth we used RMF to determine the extent of lac repression by mutant lacI repressors. File:Jr rmf 4 Figure : A Schematic representation of vector pET28a. Not that the vector has a constitutive LacI expression cassette. B BL21 DE3 cells holding the empty pET28a vector at 10mM IPTG. The vector is obviously nontoxic to cells even at high concentrations of inducer. C Decreased viability of BL21 DE3 cells harboring vector pET28a-RMF wild type at 1mM IPTG and 10mM IPTG. For our genetic experiment, we took advantage of two properties of the pET expression system. The pET expression system shows an extremely low degree of leaky expression and is therefore ideal for expression of toxic genes. In order to increase repression of lac-controlled expression in absence of inducer, the pET vector series contains a constitutive LacI expression cassette encoding a lacI gene that is identical to the lacI gene provided by the registry as part [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] and can therefore be converted by simple site-directed mutagenesis into the LacI IS mutants we set out to study. In order to find out whether the LacI IS mutants were able to rescue a BL21 DE3 cell harboring the mutated pET28a-RMF plasmid at even elevated concentrations of inducer, we subcloned RMF into the expression vector and subjected the expression vector to site-directed mutagenesis. In addition, we tested the impact of empty plasmid and pET28a-RMF with wild-type lacI on the viability of cells at elevated IPTG concentrations. In order to perform this genetic experiment, we amplified RMF from E. coli strain DH5-alpha DNA using forward primer 5’-cgcggatccgaaaacctgtattttcagggcaagagac aaaaacgagatcgcctg and reverse primer 5’-ccgctcgagttattaggccattactaccctgtcc (reaction setup was 35ul water, 10ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion HF buffer, 1ul 10mM dNTPs, 1ul 25uM forward primer, 1ul 25uM reverse primer, 0.5ul DH5-alpha genomic DNA, 0.5ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion Hot-start polymerase; thermocycler program was 98C for 3min, cycle start: 98C for 10s, 55C for 30s, 72C for 10s, cycle end, 35 repeats, 72C for 30min, 4C hold). We subsequently digested the PCR product with XhoI and BamHI and subcloned it into the pET28a vector ([http://www.merckbiosciences.com/g.asp?f=NVG/pETtable.html Novagen]) multiple cloning site. The sequence of the RMF insert was verified by sequencing. In order to determine whether the construct is expressed correctly and in order to verify the physiological reaction of E. coli cells to expression of RMF, we electroporated pET28a-RMF into BL21 DE3 cells (which hold a T7 polymerase gene on their genome and are therefore able to express genes under the T7 promoter) and plated the cells on LB-agar plates supplemented with kanamycin and found growth strongly diminished upon plating cells on IPTG containing plates. In order to verify the termination of growth after induction of RMF expression in liquid culture, we grew cells holding the plasmid in shake flasks and found that growth terminates rapidly upon induction. We prepared ribosomes from induced cells and measured their sedimentation velocity. Induced cells contain two poulations of ribosomes, one with a sedimentation velocity of 70S (suggesting monomeric ribosomes) and the other with a sedimentation velocity of 100S (suggesting dimers). Analysis of the different fractions by negative-stain transmission electron microscopy confirmed that both fractions consist of ribosomes although both of them appear monomeric in the electron microscope (probably the interaction is very weak and breaks up upon adsorption onto the carbon grid; an image of dimeric ribosomes seen in the electron microscope after the sample was treated with substantial amounts of glutaraldehyde has been published previously (31)). The two populations of ribosomes are equally found in uninduced cells, which have progressed into the stationary phase of growth, while the 100S fraction is diminished in cells during log phase and absent in RMF-knockouts (31).  Figure 5: A Growth curve of BL21 DE3 cells holding the pET28a-RMF plasmid without induction (uninduced) and after induction after 5 hours. Cells were grown in 1l of medium in 5l baffled flasks (37C, 95rpm) and induced once they had reached the exponential phase. B Ribosome profile of cells in the stationary phase and after RMF induction. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (Sorvall SLC-6000 rotor, 7200rpm, 10min, 4C) and disrupted in a cell disruptor (Constant systems). The lysate was cleared at 13000 rpm in a SLA-1500 rotor in a Sorvall refrigerated centrifuge. Supernatant was collected and layered on top of a 30% sucrose solution (50mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6; 100mM KCl; 10mM MgCl2; 1mM DTT). After centrifugation at 50000rpm for 20 hours at 4C in the preparative ultracentrifuge using a Ti70 rotor ([http://www.beckmancoulter.com Beckman Coulter]) the supernatant was decanted and the pellet resuspended in ribosome buffer (50mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6; 100mM KCl; 10mM MgCl2; 1mM DTT). The resuspended ribosomes were layered on top of a 10 to 40% (w/w) sucrose gradient, which was centrifuged in the SW32 swing rotor ([http://www.beckmancoulter.com Beckman Coulter]) at 28000 rpm for 7 hours. Ribosome bands were visualized by ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyndall_effect light scattering]) and photographed with a Nikon D80 SLR. C and D Electron micrographs of the 70S and 100S fraction show monomeric ribosomes in both fractions as the only macromolecular constituent. Ribosome samples were diluted to OD260 = 1. 7ul of ribosome solution was added to a glow discharged carbon grid ([http://www.quantifoil.com Quantifoil]) and stained with uranyl acetate according to standard protocol (1min sample adsorption, three times washing with 1% uranyl acetate solution by floatation). Samples were imaged with a [http://www.fei.com FEI] Morgagni 268 transmission electron microscope with tungsten emitter at an acceleration voltage of 100kV; 30000x magnification and recorded with a post column Gatan CCD camera. We took advantage of the constitutive lac expression cassette in the pET28a vector and used PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis to introduce lacI IS muations into the lacI generator of the pET28a-RMF vector. In order to perform this mutagenesis, we used forward primers R197F forward 5’-CGGCGCGTCTGTTTCTGGCTGGCTG R197A forward 5’-CGGCGCGTCTGGCGCTGGCTGGCTG T276F forward 5’-GGATACGACGATTTTGAAGACAGCTC T276A forward 5’-GGATACGACGATGCGGAAGACAGCTC and reverse primers R197F reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGAAACAGACGCGCCG R197A reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGCGCCAGACGCGCCG T276F reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCAAAATCGTCGTATCC T276A reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCCGCATCGTCGTATCC to introduce either a single mutation or double mutations. PCR was performed using vector pET28a-RMF as template according to the following protocol: Each reaction setup contained 35ul water, 10ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion polymerase HF buffer, 1ul 10mM dNTPs, 5ul primer mix (primers at 100ng/ul), 1ul of diluted DNA template (approximate concentration after dilution 10ng/ul), 0.5ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion Hot Start polymerase. The reaction was run with the following thermocycler program: 95C for 30sec, cycle start, 95C 30 sec, 55C 1min, 72C 3min, cycle end, 18 repeats, 72C for 30min, 4C hold. After the PCR reaction had gone to completion, 10ul of 50mM MgCl2 were added to each reaction tube to adjust the magnesium concentration for DpnI restriction digest and the contents were thoroughly mixed. 1ul of DpnI ([http://www.neb.com NEB] equivalent to 20 units) were added to each tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. The reaction was incubated in the thermocycler: 37C for 120min, 4C hold. Samples were purified with Qiaquick PCR purification kit and electroporated into BL21 DE3 cells. Transformation into BL21 DE3 cells yielded numerous colonies. For each construct eight colonies were streaked out on LB-agar supplemented with kanamycin. In order to test the repressor strength we streaked each of these clones onto plates of progressively higher IPTG concentration and monitored the growth. As a control, the unmodified vector was streaked out on plates without, with 1mM IPTG and with 10mM IPTG and IPTG toxicity was assayed by streaking cells holding an empty pET28a vector onto a 10mM IPTG plate. While empty pET28a vector is not toxic for cells even at 10mM IPTG, pET28a-RMF wild type vector prevents growth even at low concentrations of IPTG as expected. Although single colonies can be seen even at 10mM IPTG, it can be assumed that they originate from point mutations that either mutated the T7 gene, the promoter of T7 or RMF or the RMF gene. It is obvious that the great majority of cells is unviable even at 1mM IPTG and the colonies are expected to arise from single aberrations. With the mutated lacI IS as a major source of repressor we assumed that cells would be viable even at high IPTG concentration, since expression of RMF would be repressed by the mutated, IPTG-insensitive LacI IS. Indeed, cells grew normally up to an IPTG concentration of 10mM, which is 10- to 100-fold the concentration usually used for induction and, as can be seen on the following figure, growth was even more pronounced at IPTG concentrations of 1mM or even 10mM compared to growth without induction. This behavior is difficult to explain. The LacI expression cassette used in the pET vector series (accession number: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?val=EF442785 EF442785) appears to be controlled by the standard promoter TCACTGCCCGCTTTCCAGTCGGGAAACCTGTCGTGCCAGCTGCATTA taken from E. coli. This promoter is a weak, constitutive promoter, which does not appear to be regulated by IPTG, since it does not show sequence motifs reminiscent of the lac repressor binding site. It can be assumed that the population of lac repressors in the cell is dominated by the repressor mutant rather than by the wild type, since the mutant is expressed from hundreds of plasmids, while the wildtype is expressed from a single gene on the E. coli chromosome. While the wild type repressor will dissociate from the repressor binding site upstream of the T7 gene, the LacI IS mutant will not. Since IPTG does not change the ration of repressor to activator, it is difficult to explain why cells grew slightly denser at elevated IPTG concentration. Since all mutants restored viability of cells at 1mM and at 10mM IPTG, which exceeds the usual concentration of IPTG used for induction tenfold, we assume that all mutants we have generated strongly repress expression under lac control. Although we have not been able to obtain sequences of the mutations, we are confident that all described mutants strongly repress lac-controlled expression. Since RMF was deemed useful for several applications in synthetic biology, we decided to provide both, the coding sequence and an arabinose-inductible RMF generator as BioBrick. In order to produce BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142040 K142040] holding the coding sequence of RMF, we amplified RMF from pET28a-RMF using forward primer 5'-cgcggaattcgcggccgcttctagatgaagagacaaaaacgagatcgcctgg and reverse primer 5'-cgcgctgcagcggccgctactagtattattaggccattactaccctgtccgc and subcloned it into pSB1A7 using the BioBrick restriction sites. While the digest showed an insert of the expected size, sequencing unfortunately showed that the insert was not RMF. We were not able to repeat the experiment in time for submission of the BioBrick to the registry. The arabinose-inducible RMF generator [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142041 K142041], which could be used as a sort of “cellular stop switch”, has been ordered from Geneart, but has not been received in time for submission to the registry. Fluorescent protein experimentsWhile the estimation of repressor strength of the lacI IS mutants in the genetic experiment with the pET28a-RMF mutants has yielded some qualitative data suggesting that all mutants repress expression of lac controlled genes even at high IPTG concentrations, we attempted to quantify the repressor strength of different lacI IS mutants. We cloned the constitutive lacI expression cassette, which had been constructed by the iGEM team of ETH Zurich in 2007, (BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739002 BBa_I739002]) behind one of several lac-controlled fluorescent protein generators (BioBricks [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763004 I763004], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04430 J04430], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I13601 I13601], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J5526 J5526] ). The order of the assembly was directed by the intention to minimize readthrough of the RNA polymerase from the constitutive expression cassette into the lac-controlled reporter gene. Placing the lacI generator behind the fluorescent protein generator was assumed to help decreasing the background of leaky reporter protein expression.

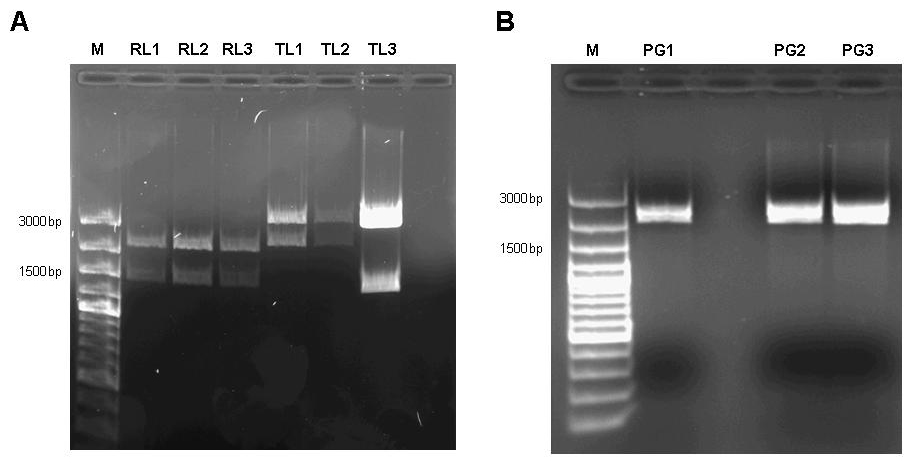

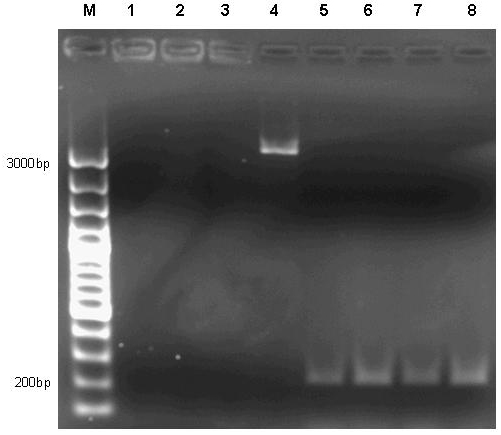

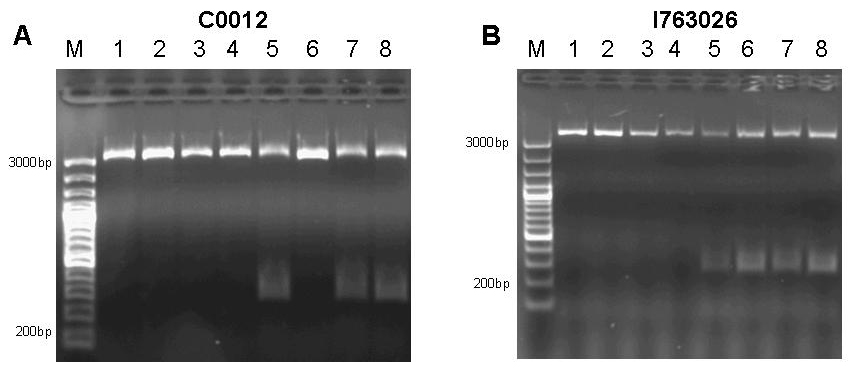

The constructs holding GFP and RFP were selected for site-directed mutagenesis, since they are easily detectable with the filter set of our plate reader and – in the case of RFP – even detectable by eye. Site directed mutagenensis was carried out by PCR using forward primers R197F forward 5’-CGGCGCGTCTGTTTCTGGCTGGCTG R197A forward 5’-CGGCGCGTCTGGCGCTGGCTGGCTG T276F forward 5’-GGATACGACGATTTTGAAGACAGCTC T276A forward 5’-GGATACGACGATGCGGAAGACAGCTC and reverse primers R197F reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGAAACAGACGCGCCG R197A reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGCGCCAGACGCGCCG T276F reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCAAAATCGTCGTATCC T276A reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCCGCATCGTCGTATCC to achieve single mutations R197A; R197F; T276A; T276F and double mutants R197A T276A; R197A T276F; R197F T276A; R197F T276F. DpnI digest was used to dispose of the template. Unfortunately, the PCR reaction has failed and we were unable to repeat it before closing of the Wiki. Assembly of the Pulse generatorWe decided to assemble the pulse generator from the constitutive tetR expression cassette [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739001 I739001] and the tet-controlled lacI generator [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026]. According to the information available at the time we started cloning, we assumed that cloning the tetR generator behind the lacI expression cassette and subsequent site-directed mutagenesis would be sufficient to construct the pulse generator. However, when the Caltech team sequenced BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026], they found that it did not contain a promoter, but rather started with the ribosome binding site. Therefore, we revised our cloning strategy and tried two different approaches. We firstly cloned the lacI generator behind the tet-controlled promoter [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] in order to assemble a part that has the deposited sequence of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026]. In the attempt to try a different approach, we at the same time cloned the tetR-generator behind the promoterless lacI generator. In the next step, we cloned the tetR expression cassette behind the lacI generator with tet-controlled promoter and subjected the assembly to site-directed mutagenesis.  Figure 7: A 1% agarose gel of XbaI/PstI test digests of plasmids holding the lac generator [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] behind the tet-controlled promoter [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] (RL1, RL2, RL3) and of XbaI/PstI test digests of plasmids holding the constitutive tetR expression cassette [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739001 I739001] behind the promoterless lacI generator [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] (TL1, TL2, TL3). The insert size agrees with the expected size in the case of RL1, RL2, RL3, TL1, TL2. TL3 apparently religated despite dephosphorylation treatment with alkaline phosphatase (CIP) and does not contain the aforementioned tetR expression cassette. B 1% agarose gel of XbaI/SpeI test digests of assembled pulse generator precursor containing BioBricks [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739001 I739001]. Insert size conforms with the expected size in all cases. Unfortunately only one of the eight mutagenensis expriments by PCR had worked by end of the Wiki deadline. However, since all mutants had shown considerable repressor strength in the previous genetic experiments, we assumed it safe to continue experimentation on this particular construct.  Figure 8: 1% agarose gel of PCR products of site directed mutagenesis of the final pulse generator assembly consisting of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739001 I739001]. Template DNA of the pulse generator precursor [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I739001 I739001] was amplified by PCR in eight different reactions using primers 276F forward 5’-GGATACGACGATTTTGAAGACAGCTC; T276A forward 5’-GGATACGACGATGCGGAAGACAGCTC; R197F reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGAAACAGACGCGCCG ; R197A reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGCGCCAGACGCGCCG; T276F reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCAAAATCGTCGTATCC ; T276A reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCCGCATCGTCGTATCC in combinations as to produce the desired mutations R197A; R197F; T276A; T276F and double mutants R197A T276A; R197A T276F; R197F T276A; R197F T276F. Each reaction setup contained 35ul water, 10ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion polymerase HF buffer, 1ul 10mM dNTPs, 5ul primer mix (primers at 100ng/ul), 1ul of diluted DNA template (approximate concentration after dilution 10ng/ul), 0.5ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion Hot Start polymerase. The reaction was run with the following thermocycler program: 95C for 30sec, cycle start, 95C 30 sec, 55C 1min, 72C 2min, cycle end, 18 repeats, 72C for 30min, 4C hold. After the PCR reaction had gone to completion, 10ul of 50mM MgCl2 were added to each reaction tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. 1ul of DpnI (equivalent to 20 units) were added to each tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. The reaction was incubated in the thermocycler following the program: 37C for 120min, 4C hold. Samples were purified with Qiaquick PCR purification kit and separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. It is obvious that the PCR reaction failed in all cases except for reaction number 4, where a small amount of product was generated. Interestingly, amplification between the primers – as evidenced by the bands slightly above 200bp in lanes 5 to 8 – nevertheless took place in the double mutant setup. In addition, since all assembly intermediates are potentially useful BioBricks for genetic circuit engineering, we decided to subject both, the lacI gene by itself (as contained in BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_C0012 C0012]) and the, as it later turned out promoterless, Biobrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] to site-directed mutagenesis to produce a set of lacI IS mutants.  Figure 9: A 1% agarose gel of PCR products of site directed mutagenesis of C0012. Template DNA of BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_C0012 C0012] was amplified by PCR in eight different reactions using primers 276F forward 5’-GGATACGACGATTTTGAAGACAGCTC; T276A forward 5’-GGATACGACGATGCGGAAGACAGCTC; R197F reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGAAACAGACGCGCCG ; R197A reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGCGCCAGACGCGCCG; T276F reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCAAAATCGTCGTATCC ; T276A reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCCGCATCGTCGTATCC in combinations as to produce the desired mutations R197A; R197F; T276A; T276F and double mutants R197A T276A; R197A T276F; R197F T276A; R197F T276F. Each reaction setup contained 35ul water, 10ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion polymerase HF buffer, 1ul 10mM dNTPs, 5ul primer mix (primers at 100ng/ul), 1ul of diluted DNA template (approximate concentration after dilution 10ng/ul), 0.5ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion Hot Start polymerase. The reaction was run with the following thermocycler program: 95C for 30sec, cycle start, 95C 30 sec, 55C 1min, 72C 2min, cycle end, 18 repeats, 72C for 30min, 4C hold. After the PCR reaction had gone to completion, 10ul of 50mM MgCl2 were added to each reaction tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. 1ul of DpnI (equivalent to 20 units) were added to each tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. The reaction was incubated in the thermocycler following the program: 37C for 120min, 4C hold. Samples were purified with Qiaquick PCR purification kit and separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The additional bands at ~300bp visible in lanes 5, 7 and 8 are PCR products that span the distance between the two sets of primers of the double mutation. B 1% agarose gel of PCR products of site directed mutagenesis of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026]. Template DNA of BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763026 I763026] was amplified by PCR in eight different reactions using primers 276F forward 5’-GGATACGACGATTTTGAAGACAGCTC; T276A forward 5’-GGATACGACGATGCGGAAGACAGCTC; R197F reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGAAACAGACGCGCCG ; R197A reverse 5’-CAGCCAGCCAGCGCCAGACGCGCCG; T276F reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCAAAATCGTCGTATCC ; T276A reverse 5’-GAGCTGTCTTCCGCATCGTCGTATCC in combinations as to produce the desired mutations R197A; R197F; T276A; T276F and double mutants R197A T276A; R197A T276F; R197F T276A; R197F T276F. Each reaction setup contained 35ul water, 10ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion polymerase HF buffer, 1ul 10mM dNTPs, 5ul primer mix (primers at 100ng/ul), 1ul of diluted DNA template (approximate concentration after dilution 10ng/ul), 0.5ul [http://www.finnzymes.com/highperformancepcr.html Finnzyme] Phusion Hot Start polymerase. The reaction was run with the following thermocycler program: 95C for 30sec, cycle start, 95C 30 sec, 55C 1min, 72C 2min, cycle end, 18 repeats, 72C for 30min, 4C hold. After the PCR reaction had gone to completion, 10ul of 50mM MgCl2 were added to each reaction tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. 1ul of DpnI (equivalent to 20 units) were added to each tube and the contents were thoroughly mixed. The reaction was incubated in the thermocycler following the program: 37C for 120min, 4C hold. Since samples were transformed into chemically competent cells, purification was skipped and samples were separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The additional bands at ~300bp visible in lanes 5, 6, 7 and 8 are PCR products that span the distance between the two sets of primers of the double mutation.

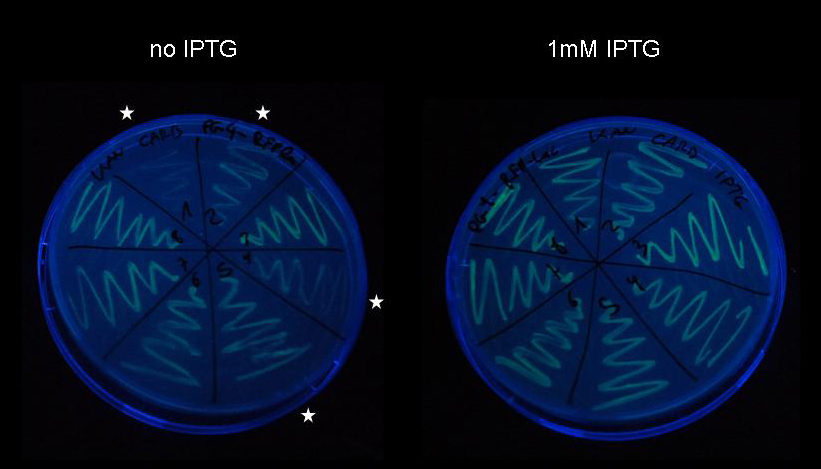

Testing of the pulse generatorA pulse generator that is of use for synthetic biology must fulfill several criteria in order to be functioning. Before activation of protein expression, leaky expression of the target protein should be as low as possible. However, upon induction, protein expression must increase markedly and remain at a high level until expression is terminated by the second signal (tetracycline). Having completed one version of the pulse generator before freezing of the Wiki ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142027 K142027]), we have been able to perform limited tests on the construct. There were two major concerns with respect to pulse generator function. Leaky expression from the target plasmid (we chose lac-controlled fluorescent protein generators) was obvious and we approached the problem by adding a LacI wild-type expression cassette to the target plasmid. (For a more advanced assembly the constitutive LacI wild-type expression cassette could be added to the pulse generator to reduce cloning effort). Another concern was that leaky expression of LacI IS could repress the lac-controlled promoter of the target gene despite absence of tetracycline making the pulse generator unresponsive to IPTG.

Prevention of leaky expressionWhile we had originally intended to use fluorescent proteins under lac-controlled promotors by themselves as target vectors, we were concerned that even the relatively low copy number (10-12 per cell) plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB3K3 pSB3K3] would offer enough binding sites for LacI to titrate away the wild-type lac repressor. Indeed, leaky expression is rather noticeable in parts [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763004 I763004], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04430 J04430], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I13601 I13601] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J5526 J5526], in some of them even with bare eyes. Therefore, we increased the number of wild-type LacI generators in the cell by including constitutive LacI expression cassettes in our target vectors. This effort resulted in devices [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142074 K142074], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142075 K142075] and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142076 K142076], which can still be induced with IPTG to yield rather strong fluorescence (except for part [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142075 K142075], which showed extremely weak fluorescence).  Figure 10: A 1% agarose gel of XbaI/PstI test restriction digests of plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB3K3 pSB3K3] holding fluorescent protein generators [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763004 I763004], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04430 J04430], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I13601 I13601] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04450 J04450]. After ligation four colonies were picked per construct and a test restriction digest was carried out to identify the plasmids holding the correct inserts. B Having subcloned [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I763004 I763004], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04430 J04430], [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I13601 I13601] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04450 J04450], respectively, into plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB3K3 pSB3K3], the resulting plasmid was linearized by SpeI/PstI restriction digest and the constitutive LacI expression cassette [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I739002 I739002] was cloned behind the fluorescent protein generators to build devices [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142074 K142074], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142075 K142075] and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142076 K142076]. After transformation, devices [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142074 K142074], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142075 K142075] and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142076 K142076] were streaked onto LB-agar plates containing 1mM IPTG and imaged under UV light with a Nikon D80 SLR As shown in the next chapter, induction of cells co-transformed with pulse generator [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142027 K142027] and target plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073] yielded a strong increase in fluorescence. Expression level upon inductionDue to the remarkable strength of the LacI IS repressor evidenced in our genetic experiment, we were concerned that if LacI IS was transcribed in small amounts despite tet-repressor regulation, which is supposed to be extremely tight, it might repress expression of the target protein despite induction and result in a pulse generator that is unable to induce expression of the target protein upon induction. In order to test induction of a lac-controlled gene in presence of the pulse generator, we co-transformed pulse generator [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142027 K142027] and target plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073] into DH5-alpha cells. We plated the cells harboring the pulse generator as well as the target plasmid on LB-agar with and without IPTG and compared the fluorescence of the colonies.  Figure : Pulse generator construct [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142027 K142027] was produced from device [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142047 K142047] using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis as described previously. After transformation by electroporation of purified PCR product into DH5-alpha cells, eight colonies were selected and plasmids were purified using Qiagen Miniprep kit. The eight plasmids have been co-transformed together with target plasmid [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K142073 K142073] into electrocompetent DH5-alpha cells and were plated on LB-agar supplemented with carbenicillin and kanamycin. Upon incubation overnight at 37C, numerous colonies appeared and one colony from each plate was streaked onto a LB-agar plate supplemented with carbenicillin and kanamycin and on a LB-agar plate supplemented with carbenicillin, kanamycin and 1mM IPTG. Cells were incubated overnight at 37C for the same duration and imaged with a Nikon D80 SLR on the UV lamp of a Kodak Gel Logic 200 imaging system. While induction is not successful in all eight strains, we see a considerable increase of fluorescence in four of them. Obviously, leaky expression of the LacI IS uninducible repressor has not occurred to the extent that would make induction impossible. Since we have not been able to get the construct sequenced yet, we have no definite proof of the functionality of the pulse generator, however we can exclude any complications arising from premature expression of LacI IS. Termination of expression upon addition of tetracyclineUnfortunately we have not been able to conduct experiments on termination of expression by induction of repressor with tetracycline before freeze of the Wiki. However, we are optimistic about conducting the experiments before the Jamboree and we might be able to present results during our talk or on our poster. References(1) Rosenberg, A. H., Lade, B. N., Chui, D. S., Lin, S. W., Dunn, J. J., and Studier, F. W. (1987) Vectors for selective expression of cloned DNAs by T7 RNA polymerase. Gene 56, 125-35. (2) Studier, F. W., and Moffatt, B. A. (1986) Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol 189, 113-30. (3) Studier, F. W., Rosenberg, A. H., Dunn, J. J., and Dubendorff, J. W. (1990) Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol 185, 60-89. (4) Beumer, K., Bhattacharyya, G., Bibikova, M., Trautman, J. K., and Carroll, D. (2006) Efficient gene targeting in Drosophila with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics 172, 2391-403. (5) Bibikova, M., Beumer, K., Trautman, J. K., and Carroll, D. (2003) Enhancing gene targeting with designed zinc finger nucleases. Science 300, 764. (6) Carroll, D. (2008) Progress and prospects: Zinc-finger nucleases as gene therapy agents. Gene Ther. (7) Carroll, D., Morton, J. J., Beumer, K. J., and Segal, D. J. (2006) Design, construction and in vitro testing of zinc finger nucleases. Nat Protoc 1, 1329-41. (8) Suckow, J., Markiewicz, P., Kleina, L. G., Miller, J., Kisters-Woike, B., and Muller-Hill, B. (1996) Genetic studies of the Lac repressor. XV: 4000 single amino acid substitutions and analysis of the resulting phenotypes on the basis of the protein structure. J Mol Biol 261, 509-23. (9) Saenger, W., Orth, P., Kisker, C., Hillen, W., and Hinrichs, W. (2000) The Tetracycline Repressor-A Paradigm for a Biological Switch. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 39, 2042-2052. (10) Hinrichs, W., Kisker, C., Duvel, M., Muller, A., Tovar, K., Hillen, W., and Saenger, W. (1994) Structure of the Tet repressor-tetracycline complex and regulation of antibiotic resistance. Science 264, 418-20. (11) Gilbert, W., and Muller-Hill, B. (1966) Isolation of the Lac Repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 56, 1891-1898. (12) Calos, M. P., Galas, D., and Miller, J. H. (1978) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. VIII. DNA sequence change resulting from an intragenic duplication. J Mol Biol 126, 865-9. (13) Coulondre, C., and Miller, J. H. (1977) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. III. Additional correlation of mutational sites with specific amino acid residues. J Mol Biol 117, 525-67. (14) Coulondre, C., and Miller, J. H. (1977) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. IV. Mutagenic specificity in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 117, 577-606. (15) Farabaugh, P. J., Schmeissner, U., Hofer, M., and Miller, J. H. (1978) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. VII. On the molecular nature of spontaneous hotspots in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 126, 847-57. (16) Kleina, L. G., and Miller, J. H. (1990) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XIII. Extensive amino acid replacements generated by the use of natural and synthetic nonsense suppressors. J Mol Biol 212, 295-318. (17) Markiewicz, P., Kleina, L. G., Cruz, C., Ehret, S., and Miller, J. H. (1994) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XIV. Analysis of 4000 altered Escherichia coli lac repressors reveals essential and non-essential residues, as well as "spacers" which do not require a specific sequence. J Mol Biol 240, 421-33. (18) Miller, J. H. (1979) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XI. On aspects of lac repressor structure suggested by genetic experiments. J Mol Biol 131, 249-58. (19) Miller, J. H. (1984) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XII. Amino acid replacements in the DNA binding domain of the Escherichia coli lac repressor. J Mol Biol 180, 205-12. (20) Miller, J. H., Coulondre, C., Hofer, M., Schmeissner, U., Sommer, H., Schmitz, A., and Lu, P. (1979) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. IX. Generation of altered proteins by the suppression of nonsence mutations. J Mol Biol 131, 191-222. (21) Miller, J. H., Ganem, D., Lu, P., and Schmitz, A. (1977) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. I. Correlation of mutational sites with specific amino acid residues: construction of a colinear gene-protein map. J Mol Biol 109, 275-98. (22) Miller, J. H., and Schmeissner, U. (1979) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. X. Analysis of missense mutations in the lacI gene. J Mol Biol 131, 223-48. (23) Schmeissner, U., Ganem, D., and Miller, J. H. (1977) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. II. Fine structure deletion map of the lacI gene, and its correlation with the physical map. J Mol Biol 109, 303-26. (24) Schmitz, A., Coulondre, C., and Miller, J. H. (1978) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. V. Repressors which bind operator more tightly generated by suppression and reversion of nonsense mutations. J Mol Biol 123, 431-54. (25) Sommer, H., Schmitz, A., Schmeissner, U., and Miller, J. H. (1978) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. VI. The B116 repressor: an altered lac repressor containing amino acid specified by both the trp and lacI leader regions. J Mol Biol 123, 457-69. (26) Friedman, A. M., Fischmann, T. O., and Steitz, T. A. (1995) Crystal structure of lac repressor core tetramer and its implications for DNA looping. Science 268, 1721-7. (27) Lewis, M., Chang, G., Horton, N. C., Kercher, M. A., Pace, H. C., Schumacher, M. A., Brennan, R. G., and Lu, P. (1996) Crystal structure of the lactose operon repressor and its complexes with DNA and inducer. Science 271, 1247-54. (28) Yamagishi, M., Matsushima, H., Wada, A., Sakagami, M., Fujita, N., and Ishihama, A. (1993) Regulation of the Escherichia coli rmf gene encoding the ribosome modulation factor: growth phase- and growth rate-dependent control. Embo J 12, 625-30. (29) Wada, A., Yamazaki, Y., Fujita, N., and Ishihama, A. (1990) Structure and probable genetic location of a "ribosome modulation factor" associated with 100S ribosomes in stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87, 2657-61. (30) Yoshida, H., Yamamoto, H., Uchiumi, T., and Wada, A. (2004) RMF inactivates ribosomes by covering the peptidyl transferase centre and entrance of peptide exit tunnel. Genes Cells 9, 271-8. (31) Yoshida, H., Maki, Y., Kato, H., Fujisawa, H., Izutsu, K., Wada, C., and Wada, A. (2002) The ribosome modulation factor (RMF) binding site on the 100S ribosome of Escherichia coli. J Biochem 132, 983-9.

|

"

"