Team:Michigan/Project

From 2008.igem.org

(→Our Project: The Sequestillator) |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

{|class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 1px; background-color:dodgerblue; border: 1px solid mediumblue; text-align:center" | {|class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 1px; background-color:dodgerblue; border: 1px solid mediumblue; text-align:center" | ||

!width="10%" align="left" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| | !width="10%" align="left" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| | ||

| + | |||

<font color=navy> | <font color=navy> | ||

| - | = '''<font color= | + | = '''<font color=royalblue size=6>Project Description</font>''' = |

| - | == <font color= | + | == <font color=royalblue size=4>Circadian Clocks</font> == |

| + | {| class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 5px; background-color:transparent; border: 1px solid transparent;text-align:center" | ||

| + | !width="70%" align="justify" valign="top" style="background:transparent; color:black"| | ||

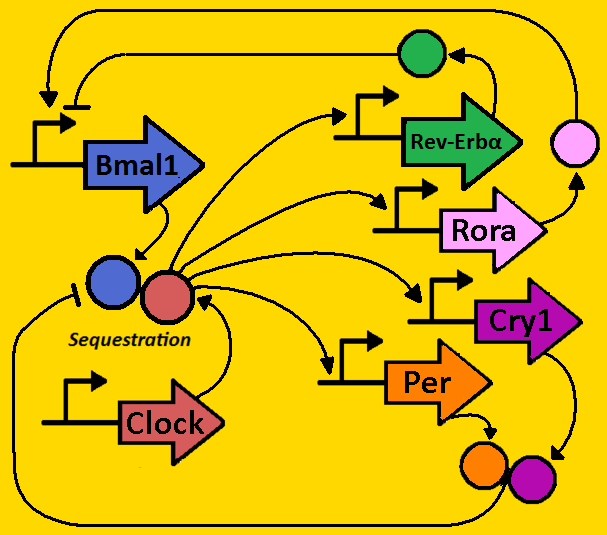

| - | + | The human body’s circadian rhythm or “clock” regulates the daily cycles of many physiological and metabolic processes such as the sleep wake cycle and feeding rhythms. The biological processes and temporal coordination are crucial to the health and survival of organisms. The processes occur with the capacity to oscillate with a wide variety of periods that are controlled by the interplay of numerous molecular factors that orchestrate complex feedback loops and processes that are fundamentally mediated by gene expression and the events that follow. | |

| - | + | In humans, circadian rhythm arises from circadian complexity and involves the activity of several components, most importantly the negative elements period homologues PER1 PER2 and the CRY1 and CRY2 crytpochrome elements along with the positive acting proteins of CLOCKA and BMAL1. | |

| + | The figure to the right depicts the molecular interactions in mammalian circadian feedback loops. The oscillator is composed of interlocking feedback loops that regulate the abundance and activity of transcription factors. These transcription factors control the expression of genes in the output pathways from the oscillator, resulting in behavioral and physiological rhythms. | ||

| - | + | The CLOCK and BMAL1 form heterodimers and activate transcription of the Per and Cry genes that form the period. The critical mechanism in the pathway occurs when PER and CRY proteins bind as heterodimers and inhibit CLOCK and BMAL1 transcription via sequestration. | |

| - | We can subdivide our clock into | + | !width="10%" align="justify" valign="top" style="background:transparent; color:black"| |

| - | + | ||

| + | [[Image:Circadian clock.PNG|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == <font color=royalblue size=4>Our Project: The Sequestillator</font> == | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 5px; background-color:transparent; border: 1px solid transparent;text-align:center" | ||

| + | !width="70%" align="justify" valign="top" style="background:transparent; color:black"| | ||

| + | |||

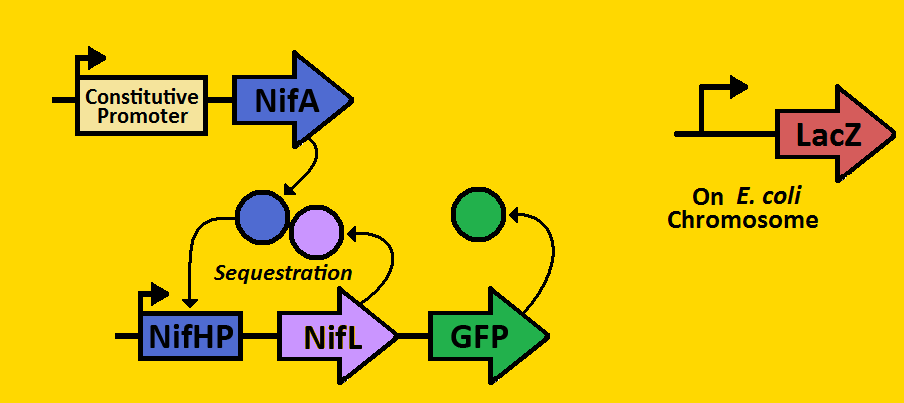

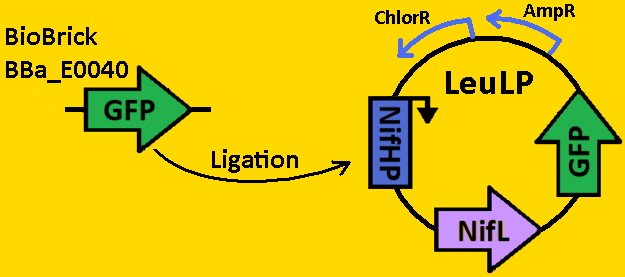

| + | We can subdivide our clock into two parts: the activator module and the repressor module. The activator module consists of the constitutive promoter driving the NifA gene, thereby producing a constant amount of NifA. We will be using three different BioBrick promoters - corresponding to low, medium, and high outputs of NifA respectively. The NifA protein binds to the nifHp promoter of the repressor module, activating transcription of the NifL gene. Once NifL dimerizes, it can bind to the NifA hexamer, hence preventing NifA from binding to NifHp. This sequestration effect provides the clock's negative feedback loop that is essential for oscillations. | ||

| + | Our hope is to put these modules on the E.coli chromosome using a BioBrick compatible Arabinose Landing Pad (our iGEM 2007 project) and a Leucine Landing Pad (a construct of a former Ninfa lab member, Dong Eun Chang). We will use E.coli strain NCM 1971, which has the nifHp driving lacZ on the chromosome. This way, we can test the amounts of NifA via Beta-galactosidase activity and test the amount of NifL via fluorescent microscopy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | !width="10%" align="left" valign="center" style="background:#transparent; color:black"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div align=center>[[Image:New full topology - gold 2 new.png|500px]]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 34: | Line 49: | ||

{|class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 1px; background-color:dodgerblue; border: 1px solid mediumblue; text-align:center" | {|class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 1px; background-color:dodgerblue; border: 1px solid mediumblue; text-align:center" | ||

| - | !width=" | + | !width="10%" align="justify" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| <font color=navy> |

| - | = '''<font color= | + | = '''<font color=royalblue size=6>Sequestillator Modeling</font>''' = |

| - | + | <div align=center>[[Image:Stochastic.png]]</div><br><br> | |

| + | <div align=center>[[Team:Michigan/Project/Modeling]]</div> | ||

| - | + | !width="10%" align="left" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| <font color=navy> | |

| - | !width=" | + | = '''<font color=royalblue size=6>Sequestillator Fabrication</font>''' = |

| + | |||

| + | <br><br><div align=center>[[Image:Fabrication.PNG|400px]]</div><br><br> | ||

| + | <br><div align=center>[[Team:Michigan/Project/Fabrication]]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {|class="wikitable" border="0" cellpadding="10" cellspacing="1" style="padding: 1px; background-color:dodgerblue; border: 1px solid mediumblue; text-align:center" | ||

| + | !width="70%" align="justify" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| | ||

| + | <font color=navy> | ||

| + | = '''<font color=royalblue size=6>Landing Pads</font>''' = | ||

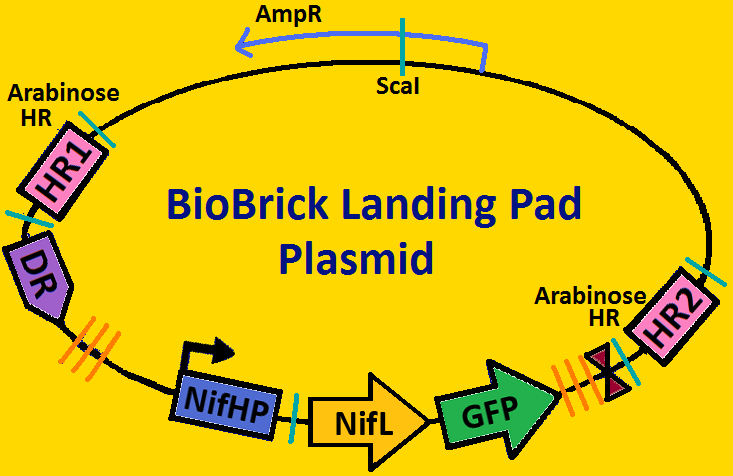

| - | + | A landing pad is tool that can be used by all synthetic biologists to insert synthetic operons onto the chromosome of <i>E. coli</i>. We will be using two landing pads for our project: the arabinose landing pad and leucine landing pad. Both of these landing pads will replace the respective metabolic operons with our desired subcloned genetic elements. The leucine landing pad was constructed by a former member of the Ninfa lab, Dong Eun Chang and the arabinose landing pad was a part of our iGEM 2007 project, and was worked on by Alyssa Delke and Khalid Miri. In using these landing pads, we wish to limit the noise in our system in order to (hopefully) obtain more sustained oscillations than previous synthetic clocks have given. | |

| + | <br> | ||

| - | + | <div align=center>[[Team:Michigan/Project/LandingPads]]</div> | |

| - | [[ | + | !width="10%" align="left" valign="top" style="background:gold; color:black"| <font color=navy> |

| + | [[Image:Landing pad plasmid - gold.png|400px|LP]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

Latest revision as of 02:09, 30 October 2008

|

|---|

|

Project DescriptionCircadian Clocks

Our Project: The Sequestillator

|

|---|

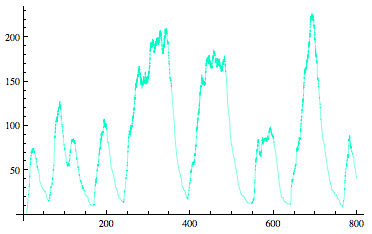

Sequestillator Modeling |

Sequestillator Fabrication |

|---|

|

Landing PadsA landing pad is tool that can be used by all synthetic biologists to insert synthetic operons onto the chromosome of E. coli. We will be using two landing pads for our project: the arabinose landing pad and leucine landing pad. Both of these landing pads will replace the respective metabolic operons with our desired subcloned genetic elements. The leucine landing pad was constructed by a former member of the Ninfa lab, Dong Eun Chang and the arabinose landing pad was a part of our iGEM 2007 project, and was worked on by Alyssa Delke and Khalid Miri. In using these landing pads, we wish to limit the noise in our system in order to (hopefully) obtain more sustained oscillations than previous synthetic clocks have given.

|

|---|

"

"