Team:Edinburgh/Modelling

From 2008.igem.org

| (7 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div id="header">{{Template:Team:Edinburgh/Templates/Header}}</div> | <div id="header">{{Template:Team:Edinburgh/Templates/Header}}</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Modelling = | ||

| + | |||

| + | Computational simulations save time and money in biological research as well as in preparation of large-scale industrial processes. In view of the pragmatic nature of our project, we sought to apply both. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [https://2008.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Team:Edinburgh/Modelling/Kinetic '''''1. Kinetic modelling''''']<br/> | ||

| + | '''''2. Process modelling''''' | ||

==Process Considerations== | ==Process Considerations== | ||

| Line 6: | Line 13: | ||

In developing a commercial version of the 'Edinburgh Process' for conversion of cellulose to starch, the following points must be considered: | In developing a commercial version of the 'Edinburgh Process' for conversion of cellulose to starch, the following points must be considered: | ||

| - | * Some of the glucose released by cellulose hydrolysis will be used by the 'Micromaize' organisms for growth and enzyme synthesis. We therefore envisage use of an 'aerobic' process (rather than an anaerobic process, as envisaged by most developers of cellulose bioconversion processes) to minimise the amount of glucose which is used in this way, leaving the maximum amount of glucose available for conversion to starch. | + | * Some of the glucose released by cellulose hydrolysis will be used by the 'Micromaize' organisms for growth and enzyme synthesis. We therefore envisage use of an '''aerobic''' process (rather than an anaerobic process, as envisaged by most developers of cellulose bioconversion processes) to minimise the amount of glucose which is used in this way, as more energy is available from aerobic degradation of glucose, leaving the maximum amount of glucose available for conversion to starch. |

| - | * Aerobic processes are more expensive to operate than anaerobic processes due to the greater cost of aeration, mixing, and cooling. However, cellulose degradation is intrinsically slower than use of soluble substrates, so the power requirements for aeration and mixing are expected to be much lower than for a typical aerobic process, and it may be possible to use a non-traditional bioreactor such as a rotating drum device, rather than a more usual (and more expensive) aerated stirred tank reactor. | + | * Aerobic processes are more expensive to operate than anaerobic processes due to the greater cost of aeration, mixing, and cooling. However, cellulose degradation is intrinsically slower than use of soluble substrates, so the power requirements for aeration and mixing are expected to be much lower than for a typical aerobic process, and it may be possible to use a non-traditional bioreactor such as a continuous tower reactor (airlift or pressure cycle reactor)or a rotating drum device, rather than a more usual (and more expensive) aerated stirred tank reactor. |

| + | * Since starch is an insoluble product (unlike glucose, the more usual target product of cellulose bioconversion processes), it can be recovered simply by harvesting and drying the cells. Further processing requirements will be dictated by the size of starch grain that can be achieved in bacterial cells. Starch granules are generally much larger than glycogen granules, but since bacteria do not naturally produce starch, we cannot accurately estimate this until some experimental evidence is available. | ||

| + | * Since starch is insoluble, it does not exert osmotic pressure and should not cause product inhibition, unlike glucose. We therefore hope that it will accumulate to much higher levels than glucose, decreasing downstream processing costs. | ||

| - | == | + | ==Process Model== |

===Equation of fermentation reaction=== | ===Equation of fermentation reaction=== | ||

| + | 1.8 '''CH''' 0.5'''O''' 0.2'''N''' + 0.41915'''O2''' = 0.62'''CH''' 1.77'''O''' 0.49'''N''' 0.24 + 0.0512'''NH3''' + 0.2745 '''H2O''' + 0.38'''CO2''' | ||

| - | |||

| - | === | + | ===Production Process Model=== |

| + | |||

| + | Below we show an outline of a possible process for large scale production of 'Micromaize' from cellulosic waste material. | ||

| + | |||

| - | |||

[[Image:Produce model.jpg]] | [[Image:Produce model.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == References == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some useful sources for information on large scale microbial processes in general, and processes for polysaccharide/food production specifically, include: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * H.-J. Rehm and G. Reed. Biotechnology, Vol.4: Measuring, Modelling and Control. | ||

| + | * Glazer, A.N. and Nikaido, H. 1995. Microbial Biotechnology: Fundamntals of applied microbiology. W.H. Freeman Co., NY. | ||

| + | * Angold, R., Beech, G., and Taggart, G. 1989. Food Biotechnology. Cambridge University Press, UK. | ||

| + | * Crueger, W., and Crueger, A. 1990. Biotechnology: a textbook of industrial microbiology. Sinauer Associates Inc, Sunderland, MA. | ||

| + | * Ratledge, C., and Kristiansen, B. (eds). 2006. Basic Biotechnology, 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK. | ||

Latest revision as of 03:53, 30 October 2008

Contents |

Modelling

Computational simulations save time and money in biological research as well as in preparation of large-scale industrial processes. In view of the pragmatic nature of our project, we sought to apply both.

1. Kinetic modelling

2. Process modelling

Process Considerations

In developing a commercial version of the 'Edinburgh Process' for conversion of cellulose to starch, the following points must be considered:

- Some of the glucose released by cellulose hydrolysis will be used by the 'Micromaize' organisms for growth and enzyme synthesis. We therefore envisage use of an aerobic process (rather than an anaerobic process, as envisaged by most developers of cellulose bioconversion processes) to minimise the amount of glucose which is used in this way, as more energy is available from aerobic degradation of glucose, leaving the maximum amount of glucose available for conversion to starch.

- Aerobic processes are more expensive to operate than anaerobic processes due to the greater cost of aeration, mixing, and cooling. However, cellulose degradation is intrinsically slower than use of soluble substrates, so the power requirements for aeration and mixing are expected to be much lower than for a typical aerobic process, and it may be possible to use a non-traditional bioreactor such as a continuous tower reactor (airlift or pressure cycle reactor)or a rotating drum device, rather than a more usual (and more expensive) aerated stirred tank reactor.

- Since starch is an insoluble product (unlike glucose, the more usual target product of cellulose bioconversion processes), it can be recovered simply by harvesting and drying the cells. Further processing requirements will be dictated by the size of starch grain that can be achieved in bacterial cells. Starch granules are generally much larger than glycogen granules, but since bacteria do not naturally produce starch, we cannot accurately estimate this until some experimental evidence is available.

- Since starch is insoluble, it does not exert osmotic pressure and should not cause product inhibition, unlike glucose. We therefore hope that it will accumulate to much higher levels than glucose, decreasing downstream processing costs.

Process Model

Equation of fermentation reaction

1.8 CH 0.5O 0.2N + 0.41915O2 = 0.62CH 1.77O 0.49N 0.24 + 0.0512NH3 + 0.2745 H2O + 0.38CO2

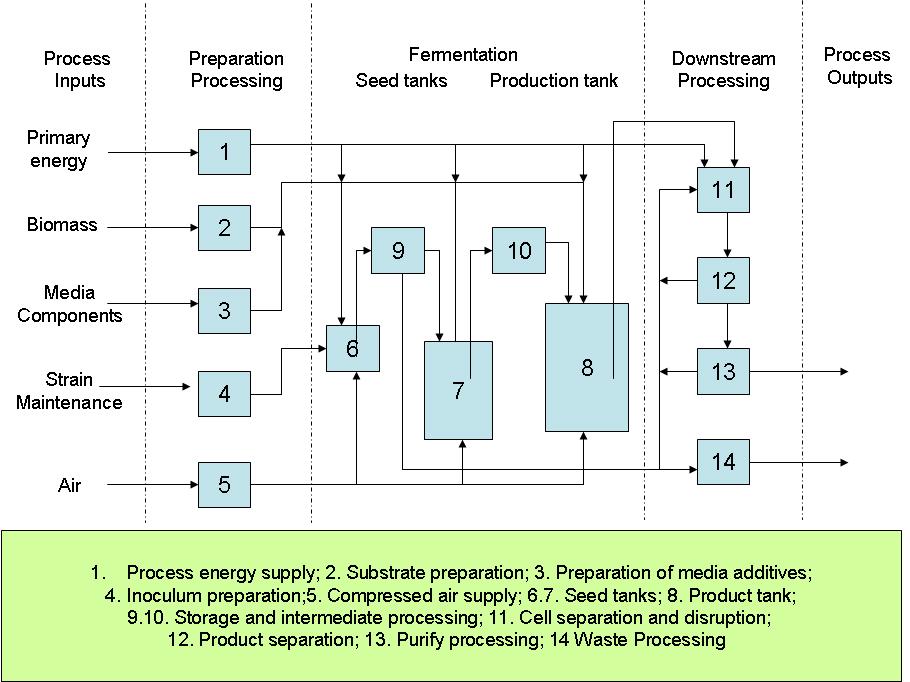

Production Process Model

Below we show an outline of a possible process for large scale production of 'Micromaize' from cellulosic waste material.

References

Some useful sources for information on large scale microbial processes in general, and processes for polysaccharide/food production specifically, include:

- H.-J. Rehm and G. Reed. Biotechnology, Vol.4: Measuring, Modelling and Control.

- Glazer, A.N. and Nikaido, H. 1995. Microbial Biotechnology: Fundamntals of applied microbiology. W.H. Freeman Co., NY.

- Angold, R., Beech, G., and Taggart, G. 1989. Food Biotechnology. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Crueger, W., and Crueger, A. 1990. Biotechnology: a textbook of industrial microbiology. Sinauer Associates Inc, Sunderland, MA.

- Ratledge, C., and Kristiansen, B. (eds). 2006. Basic Biotechnology, 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

"

"