Team:Caltech/Project/Phage Pathogen Defense

From 2008.igem.org

(→rcsA Induction) |

(→rcsA Induction) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

{{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

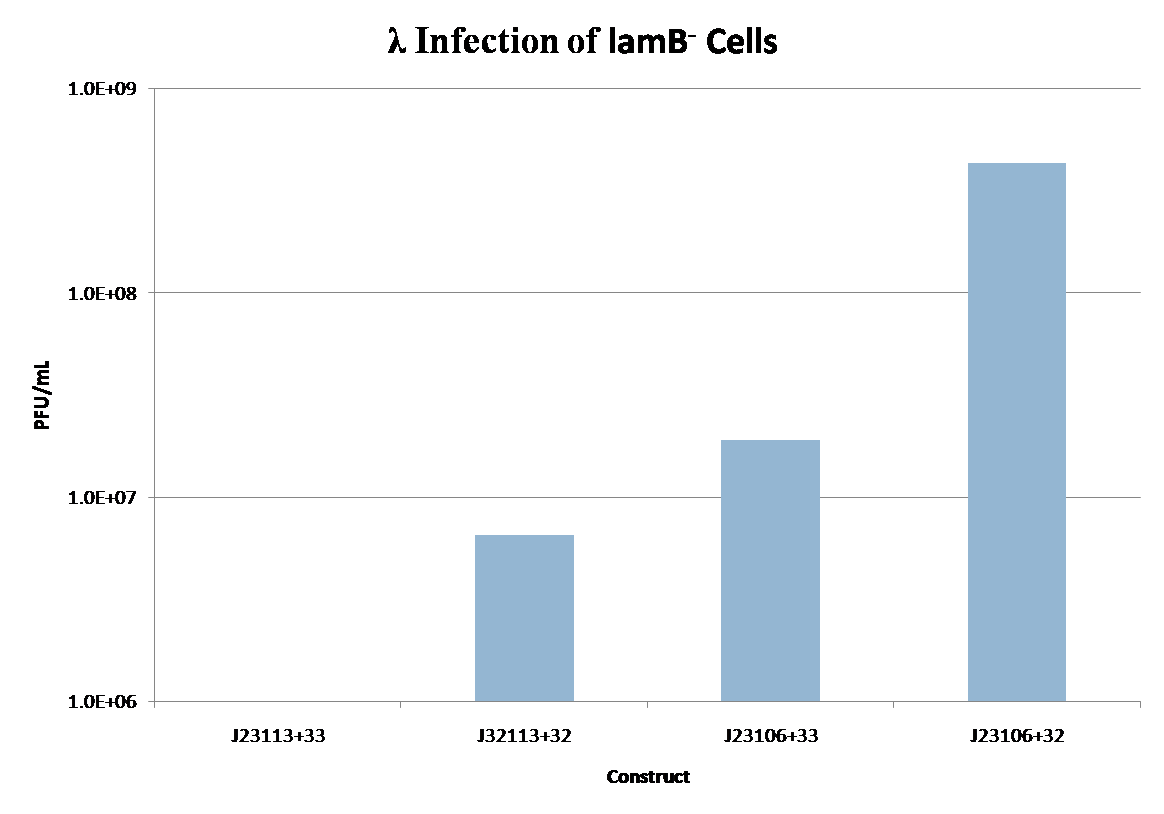

| - | [[Image:Rcsainduction.png|600px|thumb|center|Figure | + | [[Image:Rcsainduction.png|600px|thumb|center|Figure 5 - ''rscA'' induction of phage production. In this figure, each construct was infected with λ phage and lysogens were selected. Lysogens were grown to OD600=0.1 and rcsA was induced with 10 nM of AHL. 1.5 hours after induction, the supernatant was used to titer wildtype stock of ''E. coli''. Plaques were counted to calculate the phage concentration inside the supernatant after induction. For more information see [[Team:Caltech/Protocols/rcsA_Lysogen_Induction|<font style="color:#BB4400">induction protocol.</font>]]]] |

{{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===''cI'' reduces ''rcsA'' induction=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The high level of background phage induction in the strongest AHL inducible rcsA switch was not optimal. If the high basal phage levels could be reduced, then the dynamic range of the inducible switch can be greatly increased. cI, the λ repressor, has been shown to directly inhibit UV induction of lysogens [13], and rcsA seems competitively interact with cI in λ induction [7]. Both of these reasons suggest that increased concentration of the λ repressor should lead to lower phage induction levels. cI was constitutively expressed downstream of the strongest AHL inducible switch. As expected, expression of cI reduces the phage release and rcsA induction in both the off-state as well as the induced state. Phage concentration was reduced by more than 1.5x106 pfu/mL in both control and induced states. In Figure 5, for the construct expressing cI, there is an 8 fold increase in phage concentration between induced and un-induced states, more than double the dynamic range of the construct without cI expression. | ||

| + | |||

---- | ---- | ||

Revision as of 08:13, 23 October 2008

{{Caltech_iGEM_08| Content=

Introduction

There are 1014 bacterial cells that naturally reside in the human gut, an order of magnitude greater than all the cells in the body. Humans enjoy a mutualistic relationship with intestinal microbiota, wherein the microorganisms perform a host of useful functions, such as processing unused energy substrates, training the immune system, and inhibiting growth of harmful bacterial species [1]. However, not all bacteria populations within the human intestine are benign. There are many pathogenic bacteria which cause a wide variety of diseases when present in the human gut. As one example, cholera is one of the most widespread and damaging of such infectious microorganisms, with the World Health Organization reporting 132,000 cases in 2006 [2]. But cholera is just one of many examples. In the United States alone, there were more than 325,000 hospitalizations from food-borne illnesses in the year of 2006 [3]

There are many medical treatments for food-borne illnesses, the most commonly prescribed being antibiotics. Unfortunately, antibiotics are indiscriminant and lead to rapid depletion of benign bacterial populations within the intestine. Due to this fact, dietary supplements have been popularized which aim to introduce beneficial bacteria back into the gut after antibiotic treatment; these substances have been termed ‘probiotics’. Natural probiotics have two main advantages: they provide useful functions for the host and they competitively inhibit growth of pathogenic bacteria. Natural probiotics do not convey any more advantages than bacteria in a healthy human intestine. Modern synthetic biology techniques should allow us to create an engineered probiotic that goes beyond the limitations of natural probiotics. The viability of such engineered probiotics within humans has already been established [4]. As part of a collaborative effort by the Caltech iGEM team to create a novel probiotic with improved medical applications, this project focuses on engineering a pathogen defense system within E. coli..

System Design

The engineered probiotic acts as a delivery vehicle for phage into the large intestine. There are four important design goals for such as system: (1) the system releases phage into the large intestine, (2) the production of phage is regulated with a high dynamic range between a distinct on and off state, (3) the system can target a wide range of pathogenic bacteria, and (4) the system integrates well within the existing iGEM probiotic.

An obvious delivery mechanism would be the adaptation of natural lysogens, a phase of the phage life cycle in which the phage integrates its DNA with the host organism. Lysogens lie dormant until disturbed by some external stimuli, but can be stimulated to enter the lytic cycle and release phage. There is one major limitation to this method: phage released will be specific to the lysogenic hosts, E. coli. We can avoid this limitation by incorporating as a lysogen a phage which is not normally infectious to E. coli. This phage could potentially target pathogenic bacteria besides E. coli. To demonstrate the feasibility of this approach, a simple model system was developed using λ phage and JW3996-1, a strain of E. coli immune to λ infection due to lamB deletion[5]. In this model, the host is immune to infection unless lamB is expressed on a plasmid. After infection and selection for lysogens, the lamB plasmid is counterselected against to regain immunity. Extending this model to a more realistic situation, we envision using a phage which targets a pathogenic bacterial species, constitutively expressing the phage receptor within E. coli to create lysogens, and inducing the lysogens to infect non-E. coli pathogenic bacteria.

The second plasmid which must be designed controls the induction of the lysogens to release phage into the environment. Control of this aspect of the system is vital for integration with the overall iGEM project. The induction of λ phage lysogens has been explored since 1950 [6], and serves as a model system for the study of other temperate phages. The most famous induction mechanism is ultraviolet radiation (UV). In UV induction of λ lysogens, UV induced DNA damage activates the cellular SOS mechanism, which activates the expression of RecA, a protein involved in SOS response. RecA, in turn, cleaves the λ repressor and leads to phage activation. In this study, activation of the recA pathway was not readily feasible, so an alternative effector was used to elicit induction. A secondary plasmid expressing the E. coli regulatory gene, rcsA, is used as the trigger for λ phage induction. rcsA is one of several regulatory genes which provide a recA independent pathway for λ induction[7]. Overexpression of rcsA leads to λ induction, and, furthermore, rcsA appears to directly compete with the λ suppression gene cI. [6] In this project, rcsA is used to trigger phage production. The effectiveness and dynamic range of rcsA induction is explored.

Constructs

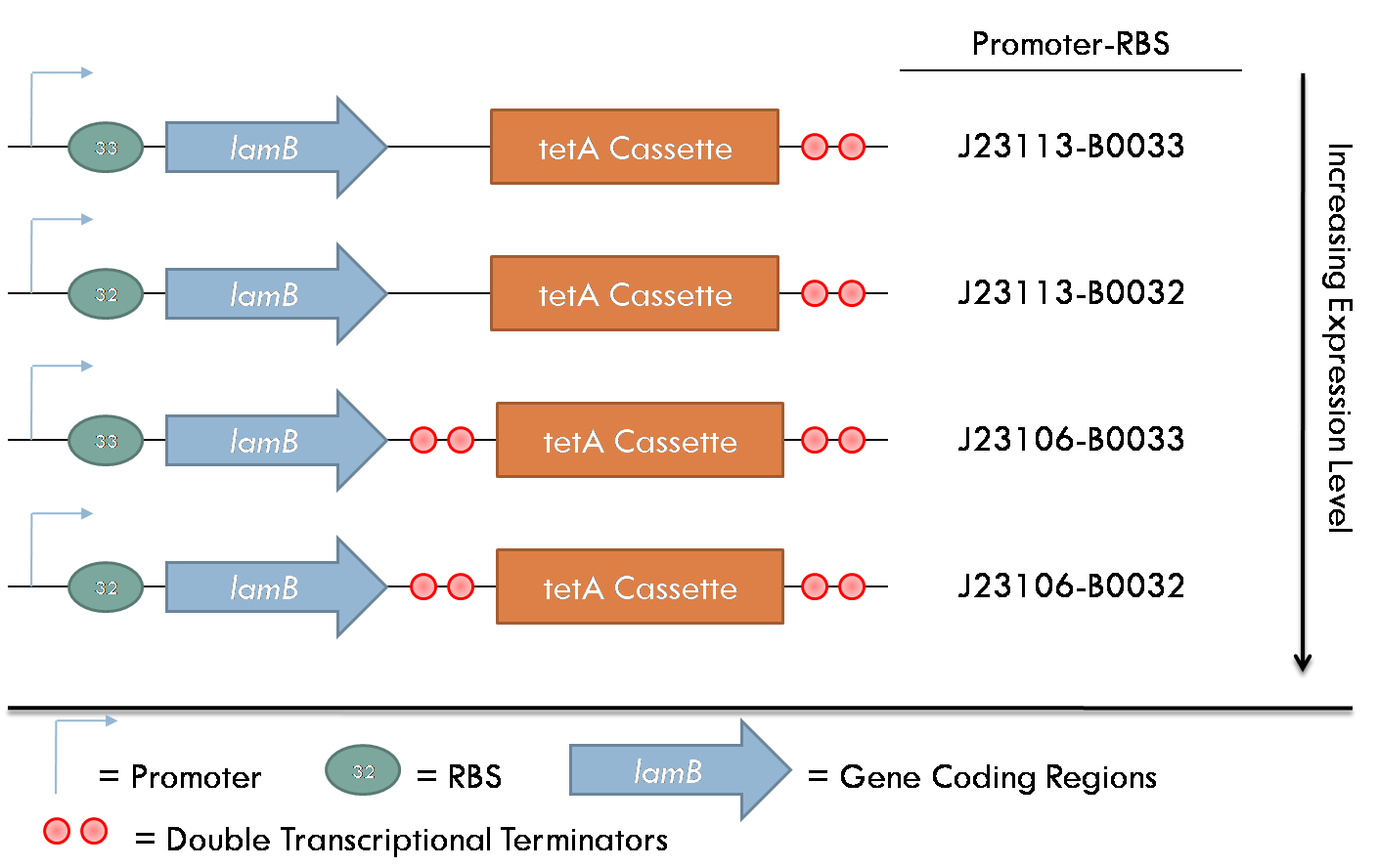

All constructs were made with standard assembly methods. "lamB" and "rcsA" were cloned out of DH10B genomic DNA. Two families of plasmids were created for this project. The first consists of plasmids which express the lamB receptor and the tetracycline resistance cassette. The level of lamB expression required for λ phage infection as unknown, thus, strength of the promoter/RBS combination upstream of lamB was varied between the four constructs of this family.

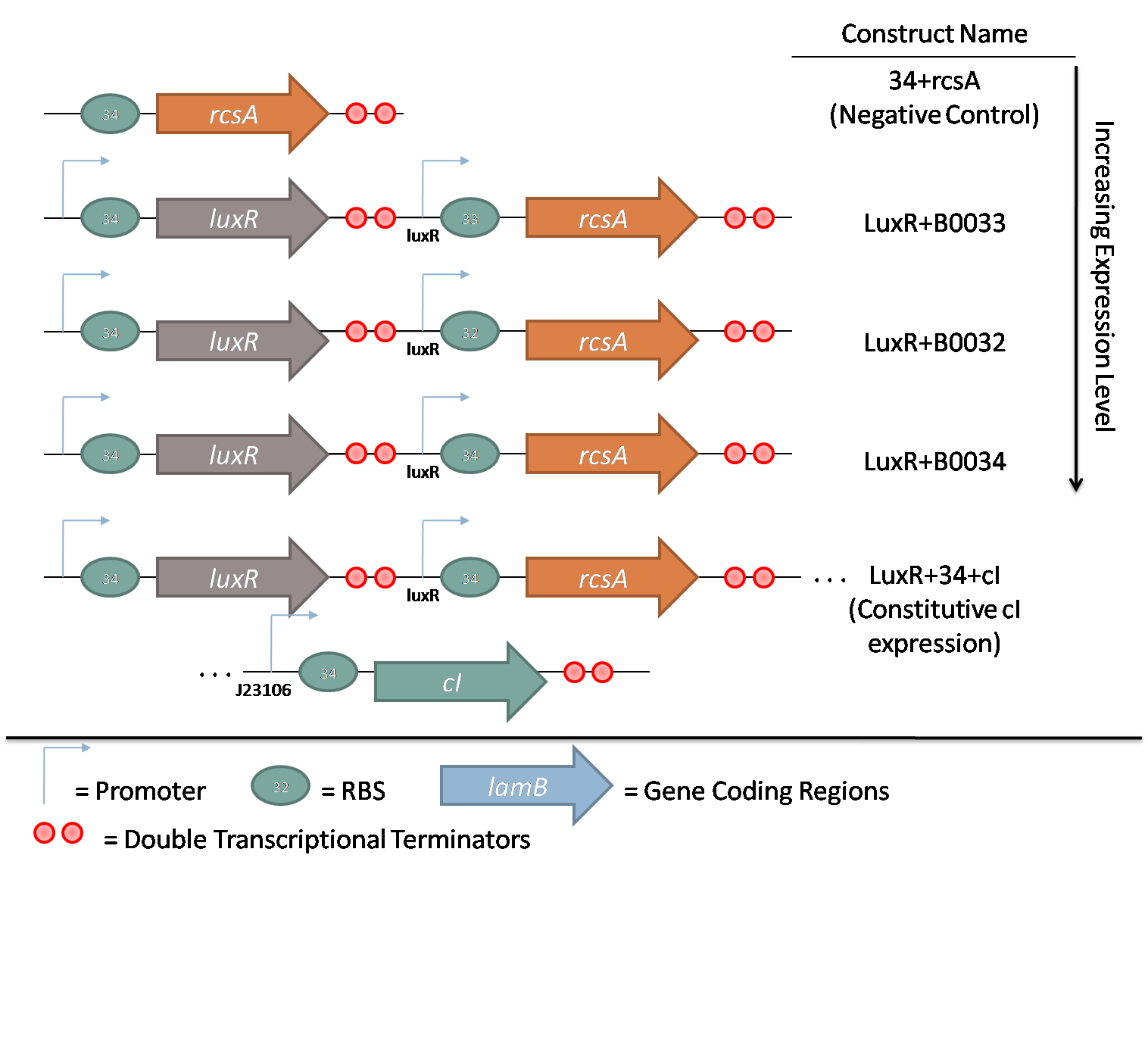

The second family consists of constructs used to characterize rcsA induction of λ phage. rcsA was placed downstream of an acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) inducible promoter, LuxR. This promoter was extensively characterized by Doug for the oxidative burst project. Using flow cytometry data, the peak response for this promoter was determined to be 10 nM AHL. Constructs with 3 different RBSes in front of rcsA were created to characterize the response of induction. Furthermore, a promoterless rcsA construct was created as a negative control, and a construct with constitutively active λ repressor cI driven by J23106 was also assembled.

Results

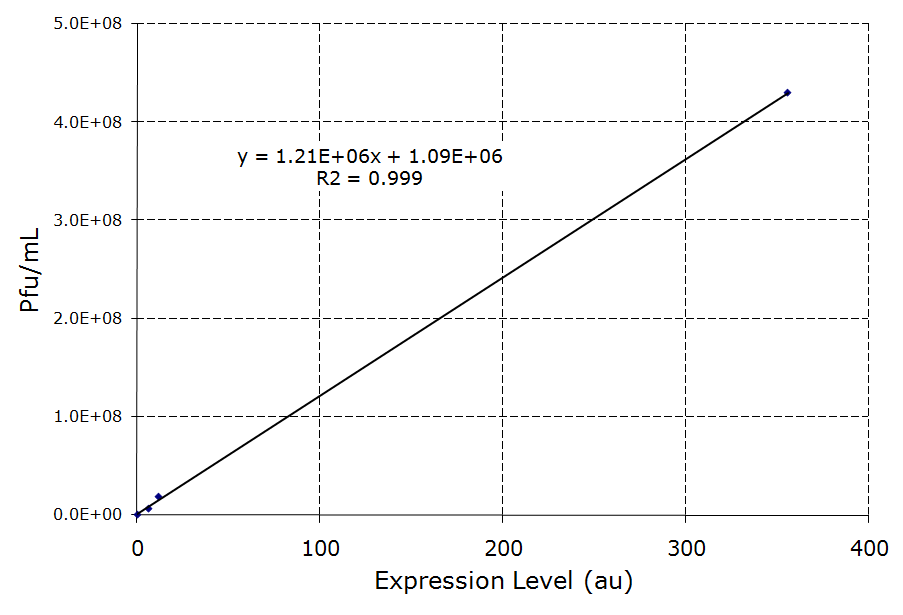

lamB Infection

lamB- cells were successfully infected by λ phage while constitutively expressing the lamB receptor. Furthermore, the level of infection directly correlated with the level of lamB expression , suggesting that phage infection was limited by the presence of lamB receptors. Next, lysogens were selected using chloramphenicol resistance. The presence of the lamB/tetA construct within the lysogens was confirmed with colony PCR. This plasmid was successfully removed via tetracycline counterselection. This procedure successfully established a lysogenic strain lacking the lamB receptor and thus immune to phage infection.

rcsA Induction

Overexpression of rcsA led to induction of λ lysogens. rcsA was placed downstream of an AHL inducible promoter and overexpressed through induction with 10 nM AHL. Following induction, phage concentration in the supernatant was recorded through titering. This concentration was compared to the phage concentration in the supernatant without rcsA overexpression, given by a construct where rcsA is not driven by a promoter. The data show a 40 fold increase in phage concentration between the promoter-less rcsA construct and the strongest AHL induced rcsA construct (Figure 5, columns 1 and 4). The promoter-less rcsA construct should accurately represent background phage levels for the lysogen absent of any rcsA expression. Further work was done to characterize the response of the AHL inducible switch under three different ribosome binding sites (RBSs). The data show induction efficiency is directly correlated with strength of rcsA overexpression (Figure 5, columns 2-4). In each of the constructs, there is a 3 to 5 fold increase in phage levels after induction with 10nm AHL. This increase does not accurately reflect the dynamic range of the AHL inducible promoter, because it does not take into account the background phage levels without the promoter. In the weaker RBSs (B0032 and B0033), the phage concentration from the uninduced supernatant is comparable to the background level from the promoter-less construct (Figure 5, columns 1-3). Thus, in these inducible promoter systems, there is high dynamic range and negligible background compared to basal phage concentrations.. However, in the strongest RBS (B0034), the uninduced phage level is an order of magnitude higher than the promoter-less background level. This high basal level expression suggests that the higher expression levels due to the strong RBS is leading to leaky rcsA activation of the phage lytic cycle.

cI reduces rcsA induction

The high level of background phage induction in the strongest AHL inducible rcsA switch was not optimal. If the high basal phage levels could be reduced, then the dynamic range of the inducible switch can be greatly increased. cI, the λ repressor, has been shown to directly inhibit UV induction of lysogens [13], and rcsA seems competitively interact with cI in λ induction [7]. Both of these reasons suggest that increased concentration of the λ repressor should lead to lower phage induction levels. cI was constitutively expressed downstream of the strongest AHL inducible switch. As expected, expression of cI reduces the phage release and rcsA induction in both the off-state as well as the induced state. Phage concentration was reduced by more than 1.5x106 pfu/mL in both control and induced states. In Figure 5, for the construct expressing cI, there is an 8 fold increase in phage concentration between induced and un-induced states, more than double the dynamic range of the construct without cI expression.

Conclusion

"

"