Team:Princeton/Project

From 2008.igem.org

(→Why Neurons?) |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!--- The Mission, Experiments ---> | <!--- The Mission, Experiments ---> | ||

{{PrincetonHeader}} | {{PrincetonHeader}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| + | {|align="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:design_Princeton.jpg|600px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| - | |||

| + | ==Why Neurons?== | ||

| - | + | Neurons present a novel form of cell to cell communication, through the use of neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical compounds which relay messages between neurons and other cells through the stimulation of an action potential. They are first released in vesicle formations from the presynaptic side of the synapse, only to be received by the receptor of the neighboring cell. Once the neurotransmitter activates the receptor, an action potential based on chemical and electrical gradients is triggered. When it reaches the synapse, the same neurotransmitter is usually released and the message is carried along the pathway. | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Working with neurotransmitters also gives us the advantage of getting both inhibitory and excitatory responses after transmission. The actual effect of being excitatory or inhibitory comes from the receptors, as certain ones increase the probability that an action potential will stimulate the cell. Conversely, others have an inhibitory effect on the cell by preventing such excitatory behavior. Common inhibitory neurotransmitters include GABA and glycine, while a common excitatory neurotransmitter is glutamate. Other neurotransmitters have the potential to affect cells either way, depending on the present receptor, such as dopamine and acetylcholine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Neurons are also useful for medical applications involving neurodegeneration or other disorders of the nervous system, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Learning about the function and interaction of neurons can help to create useful tools in finding cures to these common illnesses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Description== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The goal of the Princeton iGEM team is to utilize the considerable capabilities of neurons and in particular of neuronal networks – in terms of speed of transmission of information, physical and programmable versatility – by designing neural networks using gene-regulatory circuits and microfabrication of surfaces. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Gardner et al. showed in 2003 the construction of a [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v403/n6767/pdf/403339a0.pdf toggle switch] using gene-regulatory circuits. Our project is to design a similar toggle switch with neurons. Highly differentiated neurons can be made to produce and/or respond to specific neurotransmitters; and have receptors for these neurotransmitters also. The genetic regulation determines what kinds of neurons embryonic stem cells differentiate into. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The toggle switch is constructed as follows: a cluster of pacemaker neurons constantly excites two clusters of neurons that are designed to cross-repress each other. With an external inhibitory input, either of these neural clusters can be repressed, immediately following which it ceases to repress the other cluster of neurons. This in turn represses the first cluster of neurons, which remains repressed even if the external repression is taken away. Thus, it can be held in a steady state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Since different neurotransmitters can be excitatory or inhibitory depending on the receptors, we have chosen to build our toggle switch with different 'connections' made with different neurotransmitters. The schematic below shows what the neurotransmitter connections look like. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {|align="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:toggle_Princeton.jpg|center]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | However, the toggle switch also needs to be physically laid out in such a manner as to ensure the connections needed. [https://2008.igem.org/Image:AssafRotemReasearch_Description.pdf It has been shown] that plating neurons in a specific pattern gives the emerging networks special properties determined by those patterns. Also, the directional growth of these networks is strongly influenced. Therefore, by patterning the surfaces that neurons grow on, we can direct specific network connections. This is at the heart of the architecture of the toggle switch. Since neurons grown in triangles on a microfabricated gold surface pass signals unidirectionally like diodes, they can be used to physically implement the toggle switch network described above. An image, taken from L-Edit (used to design the mask for such gold patterns) shows what the toggle switch should eventually 'look' like. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {|align="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:Pattern_Princeton.jpg|center]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 00:42, 30 October 2008

PRINCETON IGEM 2008

| Home | Project Overview | Project Details | Experiments | Results | Notebook |

|---|

| Parts Submitted to the Registry | Modeling | The Team | Gallery |

|---|

|

Why Neurons?

Neurons present a novel form of cell to cell communication, through the use of neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical compounds which relay messages between neurons and other cells through the stimulation of an action potential. They are first released in vesicle formations from the presynaptic side of the synapse, only to be received by the receptor of the neighboring cell. Once the neurotransmitter activates the receptor, an action potential based on chemical and electrical gradients is triggered. When it reaches the synapse, the same neurotransmitter is usually released and the message is carried along the pathway.

Working with neurotransmitters also gives us the advantage of getting both inhibitory and excitatory responses after transmission. The actual effect of being excitatory or inhibitory comes from the receptors, as certain ones increase the probability that an action potential will stimulate the cell. Conversely, others have an inhibitory effect on the cell by preventing such excitatory behavior. Common inhibitory neurotransmitters include GABA and glycine, while a common excitatory neurotransmitter is glutamate. Other neurotransmitters have the potential to affect cells either way, depending on the present receptor, such as dopamine and acetylcholine.

Neurons are also useful for medical applications involving neurodegeneration or other disorders of the nervous system, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Learning about the function and interaction of neurons can help to create useful tools in finding cures to these common illnesses.

Description

The goal of the Princeton iGEM team is to utilize the considerable capabilities of neurons and in particular of neuronal networks – in terms of speed of transmission of information, physical and programmable versatility – by designing neural networks using gene-regulatory circuits and microfabrication of surfaces.

Gardner et al. showed in 2003 the construction of a [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v403/n6767/pdf/403339a0.pdf toggle switch] using gene-regulatory circuits. Our project is to design a similar toggle switch with neurons. Highly differentiated neurons can be made to produce and/or respond to specific neurotransmitters; and have receptors for these neurotransmitters also. The genetic regulation determines what kinds of neurons embryonic stem cells differentiate into.

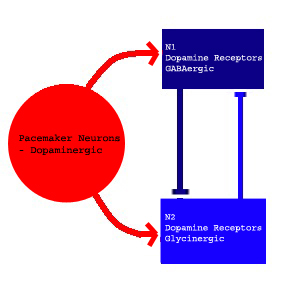

The toggle switch is constructed as follows: a cluster of pacemaker neurons constantly excites two clusters of neurons that are designed to cross-repress each other. With an external inhibitory input, either of these neural clusters can be repressed, immediately following which it ceases to repress the other cluster of neurons. This in turn represses the first cluster of neurons, which remains repressed even if the external repression is taken away. Thus, it can be held in a steady state.

Since different neurotransmitters can be excitatory or inhibitory depending on the receptors, we have chosen to build our toggle switch with different 'connections' made with different neurotransmitters. The schematic below shows what the neurotransmitter connections look like.

However, the toggle switch also needs to be physically laid out in such a manner as to ensure the connections needed. It has been shown that plating neurons in a specific pattern gives the emerging networks special properties determined by those patterns. Also, the directional growth of these networks is strongly influenced. Therefore, by patterning the surfaces that neurons grow on, we can direct specific network connections. This is at the heart of the architecture of the toggle switch. Since neurons grown in triangles on a microfabricated gold surface pass signals unidirectionally like diodes, they can be used to physically implement the toggle switch network described above. An image, taken from L-Edit (used to design the mask for such gold patterns) shows what the toggle switch should eventually 'look' like.

"

"