Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm

From 2008.igem.org

(New page: {{:Team:Newcastle University/Header}} ==Evolutionary Algorithm== ===Aim:=== Develop a system that will evolve genetic circuits represented as networks that meet the functional requireme...) |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:Newcastle University/Header}} | {{:Team:Newcastle University/Header}} | ||

| - | + | {{:Team:Newcastle University/Template:UnderTheSoftware|page-title=[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm|Evolutionary Algorithm]]}} | |

| + | <div id="maincol"> | ||

==Evolutionary Algorithm== | ==Evolutionary Algorithm== | ||

| + | <html><a name="aims"></html> | ||

| + | ===Aims and Objectives:=== | ||

| - | + | To develop a system that will evolve genetic circuits represented as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)which meet the functional requirements specified by the team's target application. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

Traditional genetic engineering techniques have built small biological circuits by hand. However, this approach will not scale to whole-organism engineering. For synthetic biology at this scale computational design will be essential. “Soft” computing techniques such as evolutionary computation and computational intelligence were developed to handle exactly this sort of large, complex, hard-to-define problem. | Traditional genetic engineering techniques have built small biological circuits by hand. However, this approach will not scale to whole-organism engineering. For synthetic biology at this scale computational design will be essential. “Soft” computing techniques such as evolutionary computation and computational intelligence were developed to handle exactly this sort of large, complex, hard-to-define problem. | ||

| - | + | The EA should: | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | * Read parts list from [[Team:Newcastle University/Parts Repository|parts repository]] | ||

| + | * Read constraints on parts assembly (from [[Team:Newcastle University/Constraints Repository|Constraints Repository]]) | ||

| + | * Assemble part models into a larger model | ||

| + | * Simulate the behaviour of the composite model | ||

| + | * Read desired 'input' behaviour from [[Team:Newcastle University/Workbench|Workbench]] | ||

| + | * Read desired 'output' behaviour from workbench | ||

| + | * Assess fitness | ||

| + | * Mutate the model | ||

| + | * Repeat the last two steps until a stopping criterion is encountered | ||

| + | * Output the fittest model as CellML (to workbench) | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <html><a name="interaction-diagrams"></html> | ||

| + | ===Interaction Diagrams=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Ea-architecture-wb.jpg|400px]][[Image:Ea-architecture-wb2.jpg|400px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above is a schematic that shows the communication required between the workbench and the EA. The workbench requests a new EAID which is created and provided by the EA. The workbench then provides the EA with all the initial data from the user including initial parts, wiring (constraints) and population size. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The user interacting with the workbench then requests the EA to run.. The EA returns information to the user on request. The current generation number the EA is working from can be requested by the user at any time. The fitness value can be returned at a generation number specified by the user. When the EA finishes evolving, or when the user at the workbench requests the EA to stop, the final composite model and fitness value are returned by the EA to the Workbench. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <html><a name="outcomes"></html> | ||

| + | ===Outcomes=== | ||

| + | The work for the EA was concluded on 1 Sept 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our aim was to develop a strain of ''B. subtilis'' which detects quorum-sensing peptides from other pathogenic gram-positive species and determines their presence by glowing a range of different colours. Our ''B. subtilis'' has a range of genes inserted that enable detection of these peptides. The issue that we had to overcome is the fact that we have more quorum-sensing peptides to detect than there are fluorescent proteins to show their presence. This makes planning the construct by hand much more difficult. Whilst there are at present only four different peptides to be detected, in the future this number could increase vastly and the ''B. subtilis'' should still be able to cope with an output of only three fluorescent proteins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is justification for the usage of artificial neural networks (ANNs) and evolutionary algorithms. Planning the construct by hand would be difficult, if not impossible. We had three layers of complexity that fit into the neural network structure, and we also wanted the potential user to be able to enter both the inputs and outputs to the network. The mapping between the ANN and the genetic circuit can be summed up as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * The input layer to the neural network is represented by the two-component genes, activated by the peptides from the four gram-positive pathogens. Each receptor represents a node. | ||

| + | * The output layer is represented by the three fluorescent proteins; GFP, YFP and mCherry. | ||

| + | * The hidden layer is an assortment of different transcription factors. | ||

| + | * The user specifies the inputs and the outputs; i.e. in the presence of said peptide, said fluorescent protein will light up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This was the starting point from which the construct was designed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="anns"></html> | ||

| + | ====Artificial Neural Networks==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are algorithms used for learning and optimisation (Engelbrecht, 1998). As the name suggests, the idea is based on the organization of neurons in the brain. An ANN is made up of three or more layers. One of these layers is the input layer, another is the hidden layer and another is the output layer. Each layer contains a number of nodes, points of contact for information flow mimicking what occurs in the nervous tissue. Each node is normally a representation of some kind of variable object; for example, a promoter(Montana, 1989). The network is usually represented as a directed graph; the links between the nodes make up what is called network topology. Each node has both a weight and a threshold value associated with it(Montana, 1989). The weight of an input to a node is the number which when multiplied with the input gives the weighted input. There is a threshold value present on each of the nodes. When the sum of the weights and inputs leading into that node are added together, if it exceeds the threshold value the node is activated. Otherwise it stays in its inactivated state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This ANN structure can be used as a base for the EA. Each node in the network represents a different genetic part. There are a number of different types of ANN including Radial Basis Function ANNs, feedforward ANNs and stochastic ANNs(Engelbrecht, 1998). This project has been constructed using a feedforward ANN. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A feedforward ANN differs from other ANNs as it has a closed topology. The input layer is connected only to the hidden layer, and the output layer is too only connected to the hidden layer (Montana, 1989). The output layer values are calculated by the propagation of the output values of the nodes in the input and hidden layers. The value of a node in the hidden or output layer is determined by the sum of each of the values of the nodes in the previous layer multiplied by the weights of each of the node connections between previous layer nodes and the current node(Montana, 1989). The ANN learns by adjusting the weights on the connections, which in the case of the network means replacing promoters with other promoters with a different binding affinity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="genetic-algorithm"></html> | ||

| + | ====The Genetic Algorithm==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Genetic algorithm is the most popular and widely used form of evolutionary algorithm. Here a population of individual chromosomes are represented as a type of data structure. This data structure can be characters, strings, bits, integers or any other appropriate type. The genome is often a fixed length binary string. There is a mutation operator, which alters a certain number of the chromosomes, and only those that satisfy the fitness criteria are allowed to recombine(Mitchell, 1996). The population size is kept constant and individuals are evaluated at each generation. Fitness is commonly evaluated as a probability proportional to fitness, or the error is measured between the observed and expected output (Peña-Reyes and Sipper, 2000). There is also a crossover operator between two selected parents, which exchange part of their genomes to form two offspring. The mutation and crossover operators preserve the population size (Peña-Reyes and Sipper, 2000). The user enters the expected output to the algorithm, the population will be evolved, and the process iterated until this solution is found (within a given error boundary)(Mitchell, 1996). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="mutation"></html> | ||

| + | ====Mutation==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The mutate function was carefully planned. There was no point in randomly changing parts, as it would be very computationally expensive. The user sets the order of parts in the workbench, and only parts of a similar type can be swapped into the hidden layer. For example, if a promoter region is mutated, only another promoter region can replace it. Thhere is a repository of parts from which the mutate function can retrieve the new parts. The order of the two-component genes is kept the same, as set by the user and regions such as ribosome-binding sites, promoters, transcription factors and sigma factors were swapped in and out of the hidden layer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Parts Repository is a SQL-accessible database full of these different parts that can be retrieved by the EA. The aim of the Constraints Repository is to enable both the user controlling the workbench and the EA to place parts next to each other and to change parts in a sensible way. Therefore if the user or mutate operator tried to design a construct that contained two unsuitable parts next to each other, it would not be allowed. The mutate operator would not be allowed to replace parts with other unsuitable parts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="pops"></html> | ||

| + | ====Populations and Fitness Functions==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | There were two different possible ways of setting up populations. It was possible to create a large population of individuals each representing a different neural network structure (or construct). It was also possible to take the evolutionary strategies approach and have a population size of just one. It was decided initially to use a population size of one. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The fitness function quantifies how optimal a solution is to a problem. For EAs there are a wide variety of different genes that can be combined and mutated, and a variety of different conditions under which this can occur. An EA often has to search across a ‘fitness landscape,’ involving many different gene combinations and conditions to fins the fittest solution. The fitness function for this EA will have to work with error values. The desired output that the user has input will be compared with the value that has fed through the network. Only when this error reaches a low enough error threshold would the fittest solution have been found. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="implementation"></html> | ||

| + | ====Discussion of Evolutionary Algorithm Implementation==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The original aim of the EA was that it would input biological Part models from the Parts Repository and evolve them using a feedforward neural network structure. Unfortunately, did not quite get this far before time ran out on the project. The EA / neural network structure however, is in place. This takes in a variety of double values as inputs and outputs and uses the complete mutate and fitness function operators to evolve these numbers to within an error threshold. The EA also has the capacity to simulate composite CellML models through the run class using the program [http://www.j-sim.org/ JSim]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The original EA was designed to: | ||

| + | * Have a feedforward neural network | ||

| + | * Integrate biological part and constraint models from the parts and constraints repositories | ||

| + | * Create composite models | ||

| + | * Mutate and evaluates fitness these part models based on numerical data held inside the models. | ||

| + | * Carry out hidden layer learning based on the user specifying inputs and outputs | ||

| + | |||

| + | The actual EA carries out the following | ||

| + | * Has a feedforward neural network | ||

| + | * Carries out hidden layer learning based on the user entering numerical inputs and outputs | ||

| + | * Creates composite models – however this step is not incorporated into the neural network part of the EA yet. | ||

| + | * Simulates models – again this is not incorporated into the neural network part of the EA yet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to time constraints and unforeseen problems with software the EA does not do everything it should in the way we would like. The software does however do everything we wanted it to. It has a learning neural network algorithm, it produces composite part models and it simulates CellML models. With some more work and more time spent on the algorithm, in conjunction with the parts and constraints repository the software will work to specifications. All of the principles that were laid out at the start have been fulfilled; they just have not come together yet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="further-reading"></html> | ||

| + | ===Further Reading=== | ||

| + | Adorf, H. (1990) A discrete stochastic neural network algorithm for constraint satisfaction problems, Neural Networks, 1990, 3, 917-924. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Engelbrecht, A.P. (1998) Selectine learning using Sensitivity analysis, Neural Networks Proceedings, 1998, ''IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence.'', '''2''', 1150-1155. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Estrada-Gil, J.K., Fernandez-Lopez, J.C., Hernandez-Lemus, E., Silva-Zolezzi, I., Hidalgo-Miranda, A., Jimenez-Sanchez, G. and Vallejo-Clemente, E.E. (2007) GPDTI: A Genetic Programming Decision Tree Induction method to find epistatic effects in common complex diseases, ''Bioinformatics'', '''23''', i167-174. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Forrest, S. (1993) Genetic algorithms: principles of natural selection applied to computation, ''Science'', '''261''', 872-878. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hallinan, J., Wiles, ''J Evolutionary Algorithms''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Karayiannis, N.B. and Mi, G.W. (1997) Growing radial basis neural networks: merging supervised and unsupervised learning with network growth techniques, ''Neural Networks, IEEE Transactions on'', '''8''', 1492-1506. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lawrence S, G.L., Tsoi, AC (1997) Lessons in Neural Network Training: Overfitting May be Harder than Expected, ''Proceedings of the Fourteenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence'', 540-545. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mitchell, M. (1996) An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms. MiT Press, 205. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Montana, D., Davis, L (1989) Training feedforward neural networks using genetic algorithms, ''Proceedings of the Eleventh International Joint Conference'', '''6'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Peña-Reyes, C.A. and Sipper, M. (2000) Evolutionary computation in medicine: an overview, ''Artificial Intelligence in Medicine'', '''19''', 1-23. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Searle, W. (1996) Stopped Training and remedies for overfitting, ''Proceedings of the 27th Symposium on the Interface'', 1995. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <html><a name="contributors"></html> | ||

===Contributors:=== | ===Contributors:=== | ||

| - | Lead: [[Mark Wappett]] | + | Lead: [[Team:Newcastle University/Mark Wappett|Mark Wappett]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="sidebar"> | ||

| + | {{:Team:Newcastle University/Template:PostItBox | ||

| + | |boxtype=bluebox | ||

| + | |title=Evolutionary Algorithm | ||

| + | |detail-text=<ul> | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#aims|Aims and Objectives]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#interaction-diagrams|Interaction Diagrams]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#outcomes|Outcomes]] | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#anns|Artificial Neural Networks]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#genetic-algorithm|Genetic Algorithm]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#mutation|Mutation]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#pops|Populations and Fitness Functions]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#implementation|Implementation]] | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#further-reading|Further Reading]] | ||

| + | <li>[[Team:Newcastle University/Evolutionary Algorithm#contributors|Contributors]] | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |link=}} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:38, 29 October 2008

Newcastle University

GOLD MEDAL WINNER 2008

| Home | Team | Original Aims | Software | Modelling | Proof of Concept Brick | Wet Lab | Conclusions |

|---|

Home >> Software >> Evolutionary Algorithm

Evolutionary Algorithm

Aims and Objectives:

To develop a system that will evolve genetic circuits represented as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)which meet the functional requirements specified by the team's target application.

Traditional genetic engineering techniques have built small biological circuits by hand. However, this approach will not scale to whole-organism engineering. For synthetic biology at this scale computational design will be essential. “Soft” computing techniques such as evolutionary computation and computational intelligence were developed to handle exactly this sort of large, complex, hard-to-define problem.

The EA should:

- Read parts list from parts repository

- Read constraints on parts assembly (from Constraints Repository)

- Assemble part models into a larger model

- Simulate the behaviour of the composite model

- Read desired 'input' behaviour from Workbench

- Read desired 'output' behaviour from workbench

- Assess fitness

- Mutate the model

- Repeat the last two steps until a stopping criterion is encountered

- Output the fittest model as CellML (to workbench)

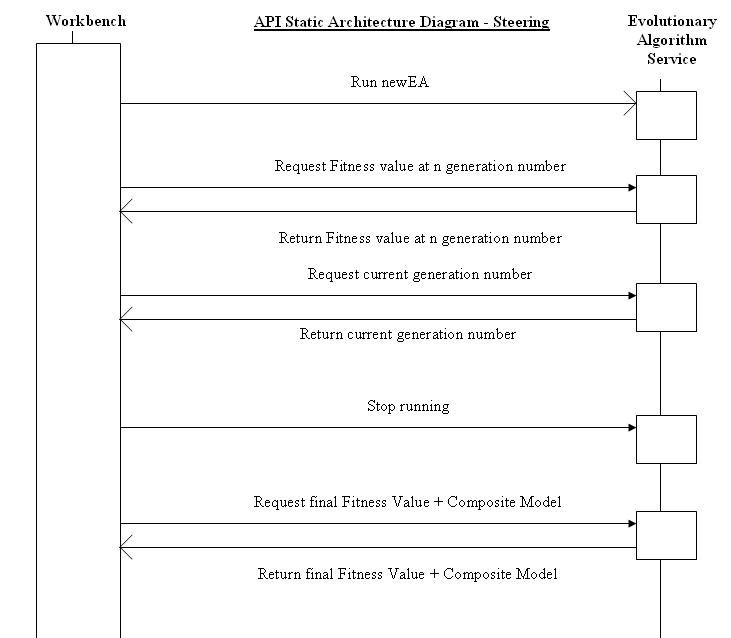

Interaction Diagrams

The above is a schematic that shows the communication required between the workbench and the EA. The workbench requests a new EAID which is created and provided by the EA. The workbench then provides the EA with all the initial data from the user including initial parts, wiring (constraints) and population size.

The user interacting with the workbench then requests the EA to run.. The EA returns information to the user on request. The current generation number the EA is working from can be requested by the user at any time. The fitness value can be returned at a generation number specified by the user. When the EA finishes evolving, or when the user at the workbench requests the EA to stop, the final composite model and fitness value are returned by the EA to the Workbench.

Outcomes

The work for the EA was concluded on 1 Sept 2008.

Our aim was to develop a strain of B. subtilis which detects quorum-sensing peptides from other pathogenic gram-positive species and determines their presence by glowing a range of different colours. Our B. subtilis has a range of genes inserted that enable detection of these peptides. The issue that we had to overcome is the fact that we have more quorum-sensing peptides to detect than there are fluorescent proteins to show their presence. This makes planning the construct by hand much more difficult. Whilst there are at present only four different peptides to be detected, in the future this number could increase vastly and the B. subtilis should still be able to cope with an output of only three fluorescent proteins.

This is justification for the usage of artificial neural networks (ANNs) and evolutionary algorithms. Planning the construct by hand would be difficult, if not impossible. We had three layers of complexity that fit into the neural network structure, and we also wanted the potential user to be able to enter both the inputs and outputs to the network. The mapping between the ANN and the genetic circuit can be summed up as follows:

- The input layer to the neural network is represented by the two-component genes, activated by the peptides from the four gram-positive pathogens. Each receptor represents a node.

- The output layer is represented by the three fluorescent proteins; GFP, YFP and mCherry.

- The hidden layer is an assortment of different transcription factors.

- The user specifies the inputs and the outputs; i.e. in the presence of said peptide, said fluorescent protein will light up.

This was the starting point from which the construct was designed.

Artificial Neural Networks

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are algorithms used for learning and optimisation (Engelbrecht, 1998). As the name suggests, the idea is based on the organization of neurons in the brain. An ANN is made up of three or more layers. One of these layers is the input layer, another is the hidden layer and another is the output layer. Each layer contains a number of nodes, points of contact for information flow mimicking what occurs in the nervous tissue. Each node is normally a representation of some kind of variable object; for example, a promoter(Montana, 1989). The network is usually represented as a directed graph; the links between the nodes make up what is called network topology. Each node has both a weight and a threshold value associated with it(Montana, 1989). The weight of an input to a node is the number which when multiplied with the input gives the weighted input. There is a threshold value present on each of the nodes. When the sum of the weights and inputs leading into that node are added together, if it exceeds the threshold value the node is activated. Otherwise it stays in its inactivated state.

This ANN structure can be used as a base for the EA. Each node in the network represents a different genetic part. There are a number of different types of ANN including Radial Basis Function ANNs, feedforward ANNs and stochastic ANNs(Engelbrecht, 1998). This project has been constructed using a feedforward ANN.

A feedforward ANN differs from other ANNs as it has a closed topology. The input layer is connected only to the hidden layer, and the output layer is too only connected to the hidden layer (Montana, 1989). The output layer values are calculated by the propagation of the output values of the nodes in the input and hidden layers. The value of a node in the hidden or output layer is determined by the sum of each of the values of the nodes in the previous layer multiplied by the weights of each of the node connections between previous layer nodes and the current node(Montana, 1989). The ANN learns by adjusting the weights on the connections, which in the case of the network means replacing promoters with other promoters with a different binding affinity.

The Genetic Algorithm

The Genetic algorithm is the most popular and widely used form of evolutionary algorithm. Here a population of individual chromosomes are represented as a type of data structure. This data structure can be characters, strings, bits, integers or any other appropriate type. The genome is often a fixed length binary string. There is a mutation operator, which alters a certain number of the chromosomes, and only those that satisfy the fitness criteria are allowed to recombine(Mitchell, 1996). The population size is kept constant and individuals are evaluated at each generation. Fitness is commonly evaluated as a probability proportional to fitness, or the error is measured between the observed and expected output (Peña-Reyes and Sipper, 2000). There is also a crossover operator between two selected parents, which exchange part of their genomes to form two offspring. The mutation and crossover operators preserve the population size (Peña-Reyes and Sipper, 2000). The user enters the expected output to the algorithm, the population will be evolved, and the process iterated until this solution is found (within a given error boundary)(Mitchell, 1996).

Mutation

The mutate function was carefully planned. There was no point in randomly changing parts, as it would be very computationally expensive. The user sets the order of parts in the workbench, and only parts of a similar type can be swapped into the hidden layer. For example, if a promoter region is mutated, only another promoter region can replace it. Thhere is a repository of parts from which the mutate function can retrieve the new parts. The order of the two-component genes is kept the same, as set by the user and regions such as ribosome-binding sites, promoters, transcription factors and sigma factors were swapped in and out of the hidden layer.

The Parts Repository is a SQL-accessible database full of these different parts that can be retrieved by the EA. The aim of the Constraints Repository is to enable both the user controlling the workbench and the EA to place parts next to each other and to change parts in a sensible way. Therefore if the user or mutate operator tried to design a construct that contained two unsuitable parts next to each other, it would not be allowed. The mutate operator would not be allowed to replace parts with other unsuitable parts.

Populations and Fitness Functions

There were two different possible ways of setting up populations. It was possible to create a large population of individuals each representing a different neural network structure (or construct). It was also possible to take the evolutionary strategies approach and have a population size of just one. It was decided initially to use a population size of one.

The fitness function quantifies how optimal a solution is to a problem. For EAs there are a wide variety of different genes that can be combined and mutated, and a variety of different conditions under which this can occur. An EA often has to search across a ‘fitness landscape,’ involving many different gene combinations and conditions to fins the fittest solution. The fitness function for this EA will have to work with error values. The desired output that the user has input will be compared with the value that has fed through the network. Only when this error reaches a low enough error threshold would the fittest solution have been found.

Discussion of Evolutionary Algorithm Implementation

The original aim of the EA was that it would input biological Part models from the Parts Repository and evolve them using a feedforward neural network structure. Unfortunately, did not quite get this far before time ran out on the project. The EA / neural network structure however, is in place. This takes in a variety of double values as inputs and outputs and uses the complete mutate and fitness function operators to evolve these numbers to within an error threshold. The EA also has the capacity to simulate composite CellML models through the run class using the program [http://www.j-sim.org/ JSim].

The original EA was designed to:

- Have a feedforward neural network

- Integrate biological part and constraint models from the parts and constraints repositories

- Create composite models

- Mutate and evaluates fitness these part models based on numerical data held inside the models.

- Carry out hidden layer learning based on the user specifying inputs and outputs

The actual EA carries out the following

- Has a feedforward neural network

- Carries out hidden layer learning based on the user entering numerical inputs and outputs

- Creates composite models – however this step is not incorporated into the neural network part of the EA yet.

- Simulates models – again this is not incorporated into the neural network part of the EA yet.

Due to time constraints and unforeseen problems with software the EA does not do everything it should in the way we would like. The software does however do everything we wanted it to. It has a learning neural network algorithm, it produces composite part models and it simulates CellML models. With some more work and more time spent on the algorithm, in conjunction with the parts and constraints repository the software will work to specifications. All of the principles that were laid out at the start have been fulfilled; they just have not come together yet.

Further Reading

Adorf, H. (1990) A discrete stochastic neural network algorithm for constraint satisfaction problems, Neural Networks, 1990, 3, 917-924.

Engelbrecht, A.P. (1998) Selectine learning using Sensitivity analysis, Neural Networks Proceedings, 1998, IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence., 2, 1150-1155.

Estrada-Gil, J.K., Fernandez-Lopez, J.C., Hernandez-Lemus, E., Silva-Zolezzi, I., Hidalgo-Miranda, A., Jimenez-Sanchez, G. and Vallejo-Clemente, E.E. (2007) GPDTI: A Genetic Programming Decision Tree Induction method to find epistatic effects in common complex diseases, Bioinformatics, 23, i167-174.

Forrest, S. (1993) Genetic algorithms: principles of natural selection applied to computation, Science, 261, 872-878.

Hallinan, J., Wiles, J Evolutionary Algorithms.

Karayiannis, N.B. and Mi, G.W. (1997) Growing radial basis neural networks: merging supervised and unsupervised learning with network growth techniques, Neural Networks, IEEE Transactions on, 8, 1492-1506.

Lawrence S, G.L., Tsoi, AC (1997) Lessons in Neural Network Training: Overfitting May be Harder than Expected, Proceedings of the Fourteenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 540-545.

Mitchell, M. (1996) An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms. MiT Press, 205.

Montana, D., Davis, L (1989) Training feedforward neural networks using genetic algorithms, Proceedings of the Eleventh International Joint Conference, 6.

Peña-Reyes, C.A. and Sipper, M. (2000) Evolutionary computation in medicine: an overview, Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 19, 1-23.

Searle, W. (1996) Stopped Training and remedies for overfitting, Proceedings of the 27th Symposium on the Interface, 1995.

Contributors:

Lead: Mark Wappett

"

"