Team:UCSF/Modeling

From 2008.igem.org

| (35 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | As we mentioned before, our team is interested in cellular memory, when the cell state established after a transient stimuli can be "remembered" for longer times. One way to establish memory is using two repressor proteins that | + | <html> |

| + | <p align="left"><a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:UCSF/Synthetic_Chromatin_Properties">Synthetic Chromatin Properties (previous)</a></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == MODELING == | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | As we mentioned before, our team is interested in cellular memory, when the cell state established after a transient stimuli can be "remembered" for longer times. One way to establish memory is by using two repressor proteins that inhibit each other's synthesis, i.e. a "toggle" switch. For the modeling portion of our iGEM project, we decided to focus on devising an intuitive model for a heterochromatin-based toggle switch to investigate some of the advantages of using heterochromatin in building such synthetic circuits. | ||

'''Starting Simple: Using the Gardner-Collins Toggle Switch Model''' | '''Starting Simple: Using the Gardner-Collins Toggle Switch Model''' | ||

| - | Previous work by the Collins group (Gardner, et al. Nature 2000) has shown that in a transcription-based circuit, at least one of the repressors needs to '''cooperatively''' repress transcription to achieve the bistability | + | Previous work by the Collins group (Gardner, et al. Nature 2000) has shown that in a transcription-based "toggle switch" circuit, at least one of the repressors needs to '''cooperatively''' repress the transcription of the other protein to achieve the necessary bistability. This cooperativity needs to be much greater than 1 for a robust bistability, where a wide bistable region in the parameter space exists for different values of the two promoter strengths. Since heterochromatin formation, by nature, is a highly cooperative phenomenon, we planned to exploit this property as a tool for building our toggle switch. |

Because only one "leg" of our toggle switch would be regulated by heterochromatin and be highly cooperative, we first wanted to check how the system would behave with only one high cooperativity constant (and with the other constant set to 1). For this, we simply implemented the Gardner model in Matlab and plotted the resulting bistable regions: | Because only one "leg" of our toggle switch would be regulated by heterochromatin and be highly cooperative, we first wanted to check how the system would behave with only one high cooperativity constant (and with the other constant set to 1). For this, we simply implemented the Gardner model in Matlab and plotted the resulting bistable regions: | ||

| Line 12: | Line 20: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| - | |width=550 align=center|Figure 1: Bistable region (shaded) expands as gamma changes, with beta | + | |width=550 align=center|Figure 1: Bistable region (shaded) expands as gamma changes, with beta set to 1. |

|} | |} | ||

| - | As | + | As illustrated in Figure 1, as the cooperativity in one leg increases, '''the area of parameter space where bistable or toggling behavior exists increases'''. |

'''Toggle Switch 2.0: Extending the Gardner Model''' | '''Toggle Switch 2.0: Extending the Gardner Model''' | ||

| - | The model by Gardner, et al was a | + | The model by Gardner, et al was a good starting point for modeling a toggle switch. However, our switch is built using heterochromatin. Accordingly, we decided to modify the model to incorporate the additional step of heterochromatin formation. To do this, we first derived equations very similar to those in the Gardner model: |

[[Image:UCSFmodel_equations2.png|center|400px]] | [[Image:UCSFmodel_equations2.png|center|400px]] | ||

| - | Equation (1) describes the transcriptional repression side of the toggle switch, e.g. Gal80 represses the expression of LexA-Sir2. Equation (2) describes the effective repression due to the presence of heterochromatin, e.g. the silencing of Gal80 expression. Equation (3) describes the formation of heterochromatin when the nucleator (LexA-Sir2) is present. Note that in this | + | Equation (1) describes the transcriptional repression side of the toggle switch, e.g. Gal80 represses the expression of LexA-Sir2. Equation (2) describes the effective repression due to the presence of heterochromatin, e.g. the silencing of Gal80 expression. Equation (3) describes the formation of heterochromatin when the nucleator (LexA-Sir2) is present. Note that in this model, we assume no cooperativity in equations (1) and (2). |

| - | We then implemented this model in Matlab and analyzed it by solving for the | + | We then implemented this model in Matlab and analyzed it by solving for the nullclines of the system: |

{| align=center | {| align=center | ||

|width=850 align=center|[[Image:UCSFmodel_nullclines.png|center|800px]] | |width=850 align=center|[[Image:UCSFmodel_nullclines.png|center|800px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| - | |width=850 align=center|Figure 2: | + | |width=850 align=center|Figure 2: Nullclines of the toggle-switch system as gamma increases. The red arrows indicate stable steady states. The black arrow indicates an unstable steady state. Note that bistability can be achieved with a high gamma even if such behavior is not observed at low gamma values, for the same set of parameter values. |

|} | |} | ||

| - | As | + | As can be seen from the above figure, for low cooperativity (gamma), the system has a single steady state (i.e. it cannot behave as a toggle switch). As gamma is increased to a high value, the nullclines begin changing so that multiple steady states exist and the system can then become bistable. This result reconfirmed that high effective cooperativity (e.g. in heterochromatin formation) can result in bistable behavior in a larger region of parameter space. |

| - | Although | + | Although this set of equations was a simplified model that captured some of the properties of a heterochromatin-based toggle, we realized that it had various problems. The fact that we are modeling heterochromatin as a concentration and using a transcriptional activation equation to describe the formation of heterochromatin was not ideal. In the next iteration, we devised a more mechanistic model of heterochromatin formation, one that could account for the high cooperativity necessary for the toggle behavior. |

| - | '''Heterochromatin Formation | + | '''Polymerization-like Heterochromatin Formation?''' |

| - | + | Traditionally, it is thought that the high cooperativity in heterochromatin formation is due to the spreading of heterochromatin from an initiation site. The spreading of heterochromatin is conceptually similar to the process of nucleation and polymerization. Accordingly, we established a model for heterochromatin formation based on a simple polymerization model. (This work was inspired by a derivation of cytoskeletal polymers in "Physical Biology of the Cell" by Phillips, Kondev, and Theriot, which is not yet published.) | |

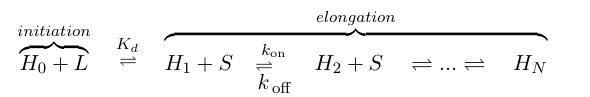

If we think of formation of heterochromatin as similar to the assembly of a protein polymer, we can write a set of reactions starting from empty DNA (H0) and LexA-Sir2 (L) initially binding to form an initiation complex. Then addition of S molecules increases the length of the heterochromatin "polymer": | If we think of formation of heterochromatin as similar to the assembly of a protein polymer, we can write a set of reactions starting from empty DNA (H0) and LexA-Sir2 (L) initially binding to form an initiation complex. Then addition of S molecules increases the length of the heterochromatin "polymer": | ||

| - | [[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer1.png|center| | + | [[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer1.png|center|500px]] |

| - | where S denotes the components involved in heterochromatin elongation (the pool of LexA-Sir2 plus endogenous Sir2). | + | where S denotes the components involved in heterochromatin elongation (the pool of LexA-Sir2 plus endogenous Sir2). |

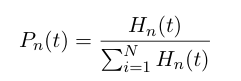

| - | At time t, | + | At any time ''t'', the probability of having a heterochromatin domain of length n is given by |

| + | [[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer2.png|center|200px]] | ||

| + | These probabilities vary with time, so we can write a set of differential equations describing the mass action kinetics of formation/loss of polymers of a specific length: | ||

| - | + | [[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer3.png|center|400px]] | |

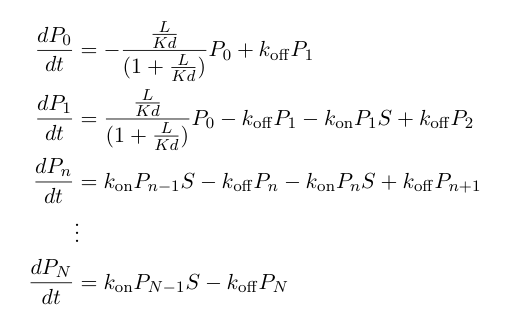

| + | Now, we can add in the equations describing the rest of the synthetic heterochromatin-based toggle circuit and implement the model in Matlab to observe its behavior: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer4.png|center|350px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first equation above describes the transcriptional repression leg of the switch, e.g. Gal80 represses the expression of LexA-Sir2. We have added an additional point of control here by including galactose as a possible input to "flip" the switch through repressing the transcriptional repression. The second equation describes the silencing by heterochromatin, where we are making the assumption that once the expected length of heterochromatin (as calculated from the probability equations above) is greater than a certain threshold length, the Gal80 gene is completely silenced and is no longer being expressed. | ||

| + | |||

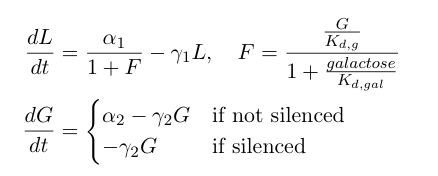

| + | These differential equations can be solved in Matlab. Below, we plot the concentrations of L and G (the two genes involved in the toggle switch) as a function of time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| align=center | ||

| + | |width=550 align=center|[[Image:UCSFmodel_polymer5.png|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

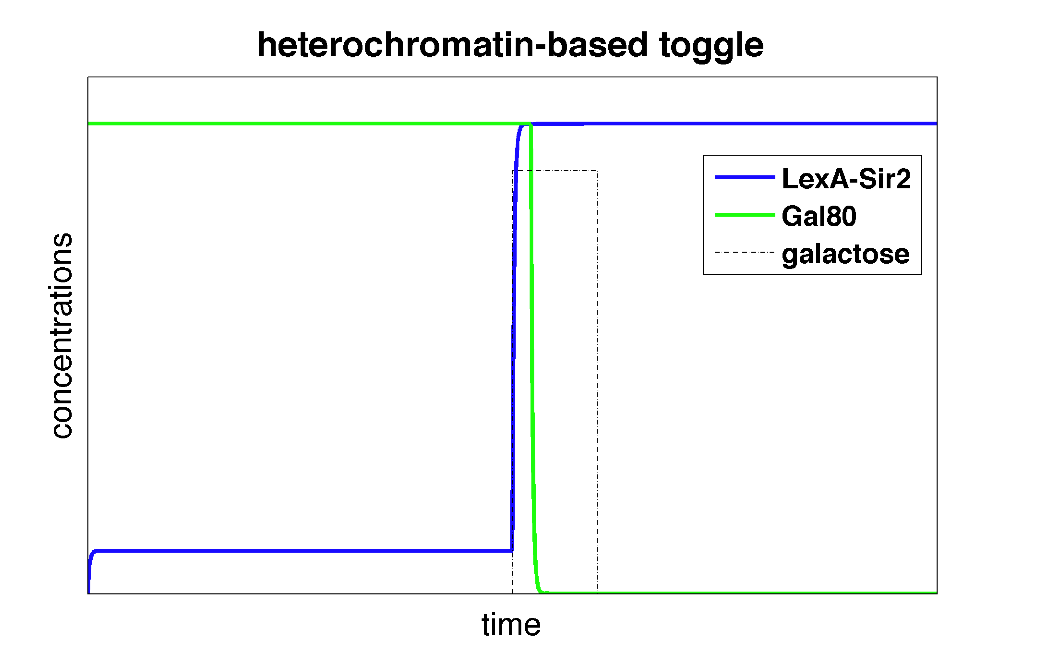

| + | |width=550 align=center|Figure 3: Time behavior of toggle switch circuit using heterochromatin polymerization model. The system starts in a high Gal80/low LexA state. Upon addition of galactose, the toggle switch is flipped to a high LexA/low Gal80 state. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the plot above, we can see that initially, the system is set to a high Gal80/low LexA state. When we add the input galactose which represses the repression of Gal80 on LexA-Sir2, the system starts expressing LexA-Sir2 and eventually, the toggle switch is flipped to and remains in a state with high LexA/low Gal80. So, we've made a toggle switch ''in silico''! | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, we wanted to investigate whether we can observe a higher robustness with respect to parameter values in the heterochromatin-based toggle versus a transcription-based toggle. Remember that the heterochromatin-based toggle has an inherently high cooperativity and our earlier results (Figure 1) suggested that such a system should be able to achieve bistability over a larger region of parameter space than a transcription-based toggle, which typically has a much lower cooperativity. | ||

| + | |||

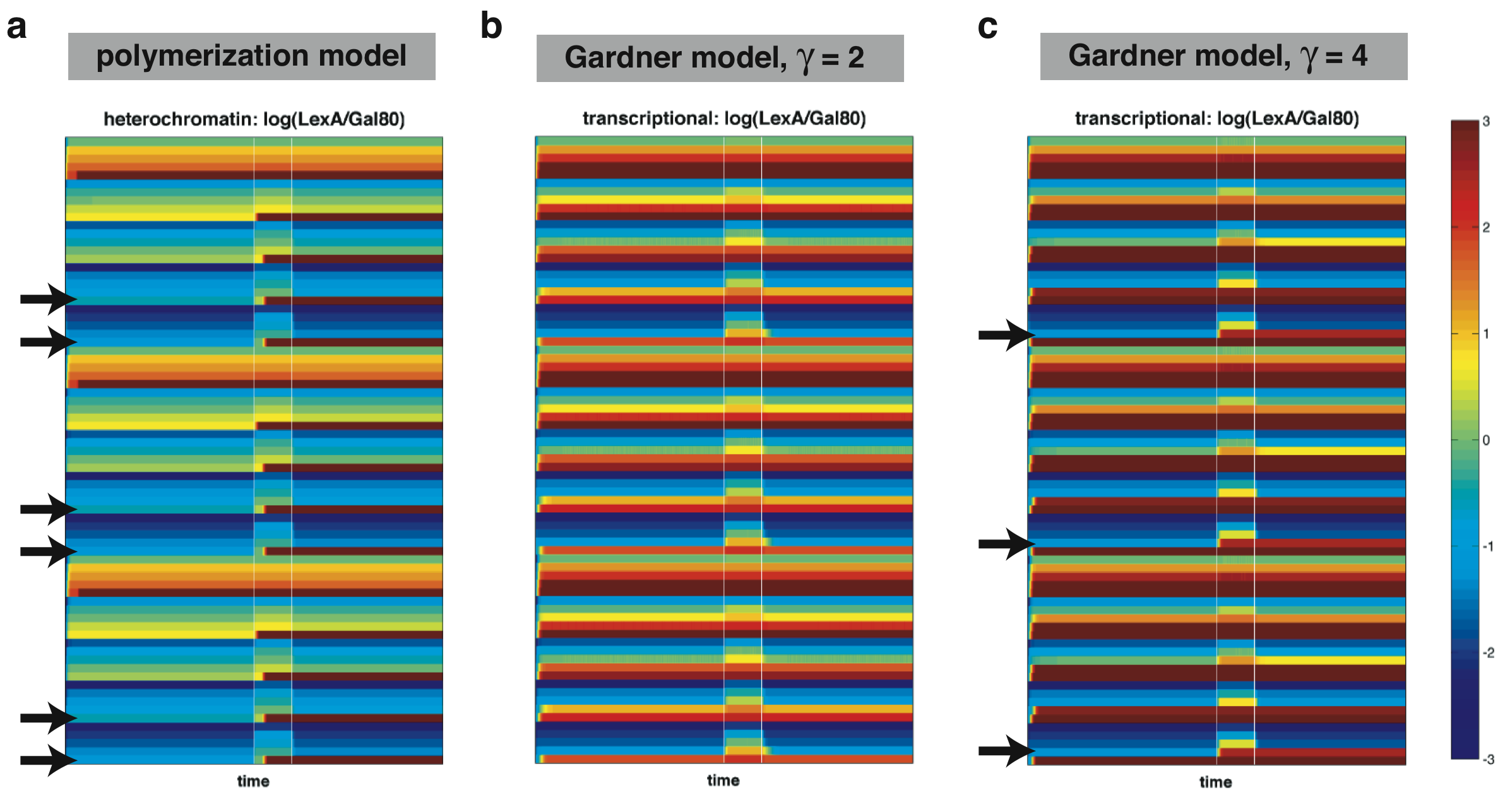

| + | A simple way to test this prediction is to compare the polymerization model and the Gardner-Collins model by varying parameters common to both models, e.g. the promoter strengths and the initial concentration of G. Note that in this comparison and similar to the analysis in Figure 1, we assume cooperativity on only one leg of the toggle switch. For the heterochromatin-based circuit, this is built into the formulation of the polymerization model and we add in no additional cooperativity constants. For the transcription-based circuit of Gardner-Collins, we set beta to 1 and gamma to a value between 2-4. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, for each particular set of parameters, we solve the differential equations to obtain the dynamic behavior of each system. To visualize the results, we take the ratio of the L concentration over the G concentration and draw as a heatmap. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| align=center | ||

| + | |width=750 align=center|[[Image:UCSFmodel_robust.png|center|730px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |width=750 align=center|Figure 4: Robustness comparison between a heterochromatin-based toggle switch using the polymerization model (a), a transcription-based toggle switch using the Gardner-Collins model with gamma=2 (b), and one with gamma=4 (c). Colors are determined by taking the ratio between the concentration of L versus the concentration of G. Black arrows indicate sets of parameters resulting in toggling behavior. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the above two figures, each row corresponds to the time behavior of the system for a particular set of parameters with the color determined by the ratio of L over G. Thus, a system which can function as a toggle switch should start off and maintain a blue state (corresponding to G > L) until the addition of galactose (first white line). After the withdrawal of galactose (second white line), the system should be able to maintain a red state (L > G). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The initial comparison performed above uses a limited number of parameter values and thus, represents a very coarse sampling of parameter space. Nonetheless, we are beginning to see that the heterochromatin-based circuit is able to achieve bistability over a larger region of parameter space compared to the transcription-based one. Future work should map out the parameter space in more detail. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Summary''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the modeling portion of our iGEM project, we investigated different ways to model a synthetic toggle switch circuit based on heterochromatin. Using a well-established model of a transcription-based toggle circuit and modifying it to account for heterochromatin formation, we first showed that bistability can be more easily achieved in circuits with very high effective cooperativity. Next, we constructed a more mechanistic model of heterochromatin formation using the idea of nucleation and polymerization and showed that such a system can display the high effective cooperativity required for bistable behavior. This model performs as a toggle switch and does so over a larger range of parameter values, as compared to a transcription-based circuit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our modeling results, in combination with those from experiments, have shown that heterochromatin formation and the resulting silencing of DNA is able to achieve much higher effective cooperativity than traditional transcriptional regulation. This feature of heterochromatin allows us to implement 'memory' in a synthetic circuit and will no doubt prove useful to synthetic biologists as we begin to think about the construction of other complex systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p align="right"><a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:UCSF/Higher_order_systems">Higher-Order Systems (next)</a></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:22, 30 October 2008

Synthetic Chromatin Properties (previous)

MODELING

As we mentioned before, our team is interested in cellular memory, when the cell state established after a transient stimuli can be "remembered" for longer times. One way to establish memory is by using two repressor proteins that inhibit each other's synthesis, i.e. a "toggle" switch. For the modeling portion of our iGEM project, we decided to focus on devising an intuitive model for a heterochromatin-based toggle switch to investigate some of the advantages of using heterochromatin in building such synthetic circuits.

Starting Simple: Using the Gardner-Collins Toggle Switch Model

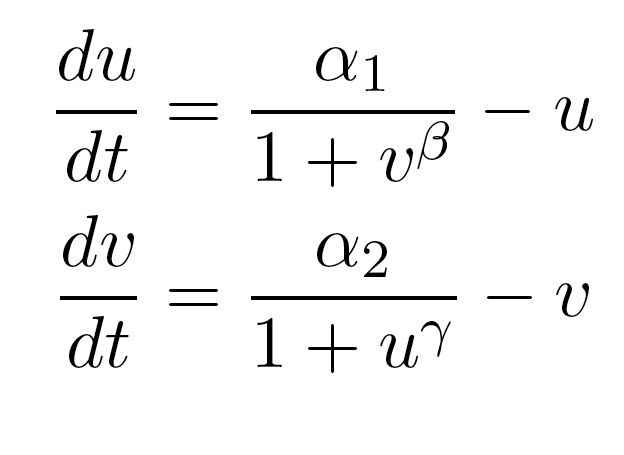

Previous work by the Collins group (Gardner, et al. Nature 2000) has shown that in a transcription-based "toggle switch" circuit, at least one of the repressors needs to cooperatively repress the transcription of the other protein to achieve the necessary bistability. This cooperativity needs to be much greater than 1 for a robust bistability, where a wide bistable region in the parameter space exists for different values of the two promoter strengths. Since heterochromatin formation, by nature, is a highly cooperative phenomenon, we planned to exploit this property as a tool for building our toggle switch.

Because only one "leg" of our toggle switch would be regulated by heterochromatin and be highly cooperative, we first wanted to check how the system would behave with only one high cooperativity constant (and with the other constant set to 1). For this, we simply implemented the Gardner model in Matlab and plotted the resulting bistable regions:

| Figure 1: Bistable region (shaded) expands as gamma changes, with beta set to 1. |

As illustrated in Figure 1, as the cooperativity in one leg increases, the area of parameter space where bistable or toggling behavior exists increases.

Toggle Switch 2.0: Extending the Gardner Model

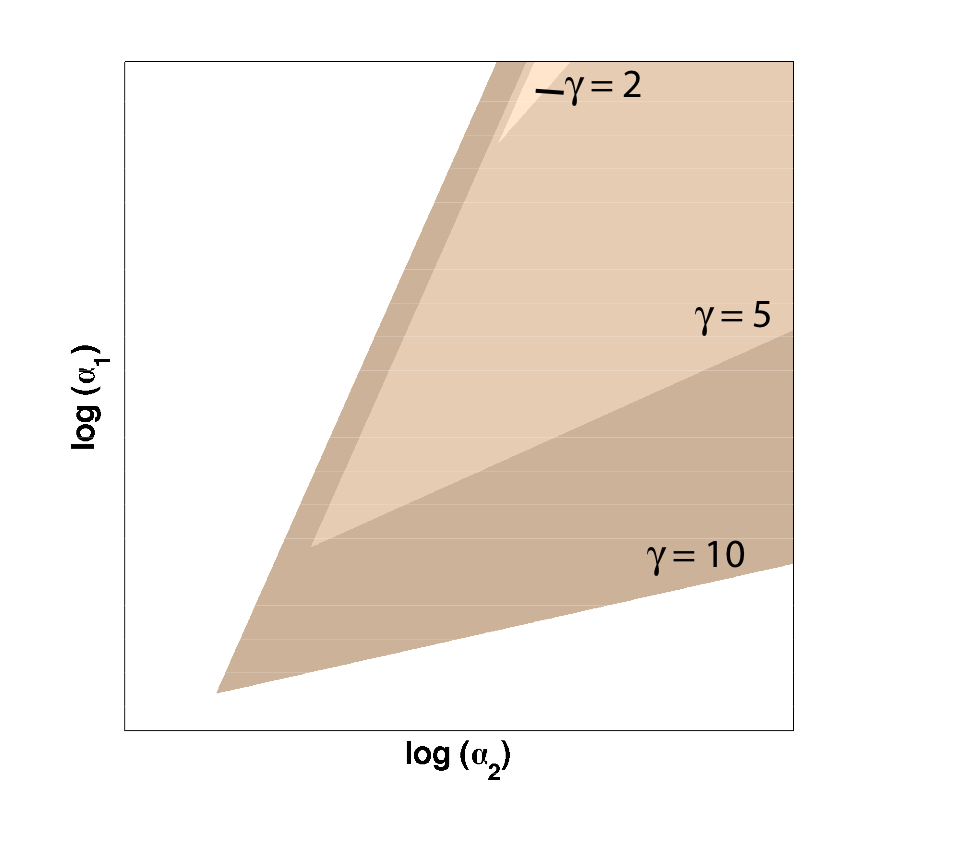

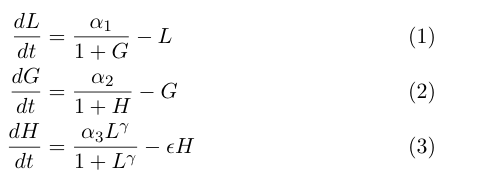

The model by Gardner, et al was a good starting point for modeling a toggle switch. However, our switch is built using heterochromatin. Accordingly, we decided to modify the model to incorporate the additional step of heterochromatin formation. To do this, we first derived equations very similar to those in the Gardner model:

Equation (1) describes the transcriptional repression side of the toggle switch, e.g. Gal80 represses the expression of LexA-Sir2. Equation (2) describes the effective repression due to the presence of heterochromatin, e.g. the silencing of Gal80 expression. Equation (3) describes the formation of heterochromatin when the nucleator (LexA-Sir2) is present. Note that in this model, we assume no cooperativity in equations (1) and (2).

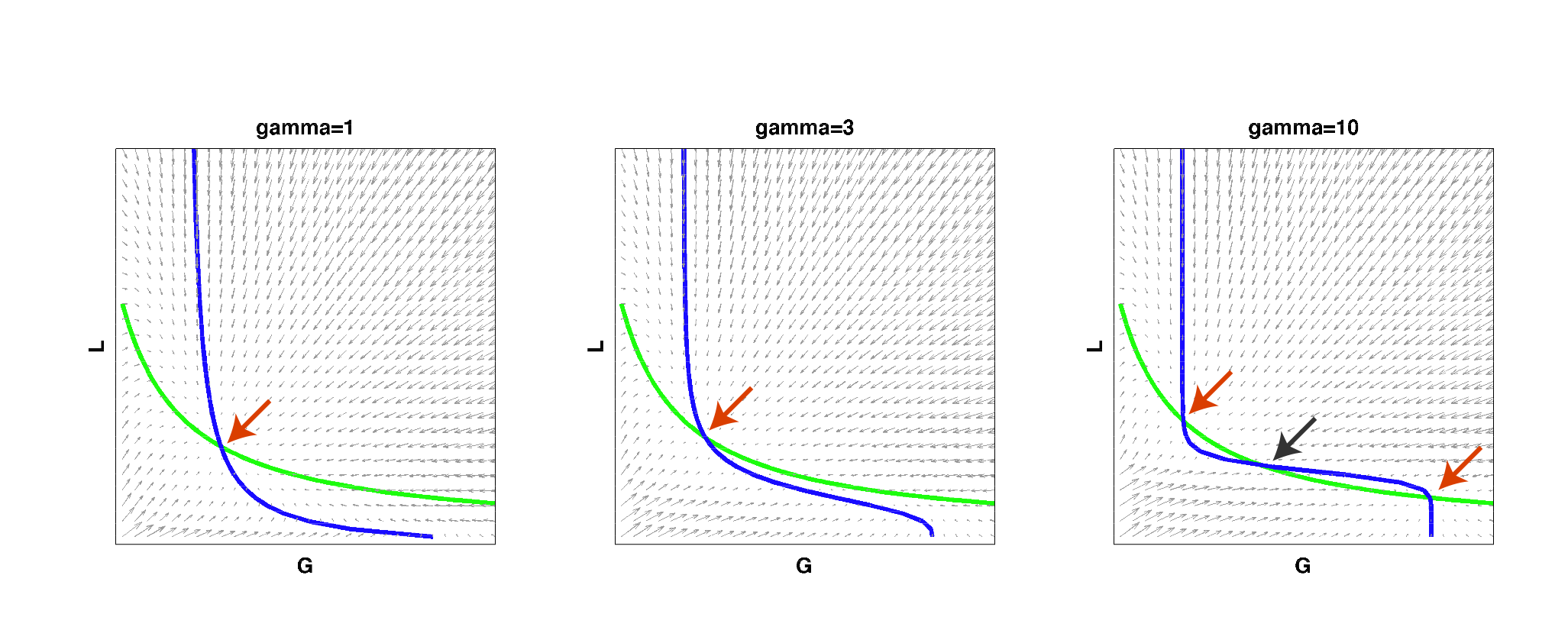

We then implemented this model in Matlab and analyzed it by solving for the nullclines of the system:

| Figure 2: Nullclines of the toggle-switch system as gamma increases. The red arrows indicate stable steady states. The black arrow indicates an unstable steady state. Note that bistability can be achieved with a high gamma even if such behavior is not observed at low gamma values, for the same set of parameter values. |

As can be seen from the above figure, for low cooperativity (gamma), the system has a single steady state (i.e. it cannot behave as a toggle switch). As gamma is increased to a high value, the nullclines begin changing so that multiple steady states exist and the system can then become bistable. This result reconfirmed that high effective cooperativity (e.g. in heterochromatin formation) can result in bistable behavior in a larger region of parameter space.

Although this set of equations was a simplified model that captured some of the properties of a heterochromatin-based toggle, we realized that it had various problems. The fact that we are modeling heterochromatin as a concentration and using a transcriptional activation equation to describe the formation of heterochromatin was not ideal. In the next iteration, we devised a more mechanistic model of heterochromatin formation, one that could account for the high cooperativity necessary for the toggle behavior.

Polymerization-like Heterochromatin Formation?

Traditionally, it is thought that the high cooperativity in heterochromatin formation is due to the spreading of heterochromatin from an initiation site. The spreading of heterochromatin is conceptually similar to the process of nucleation and polymerization. Accordingly, we established a model for heterochromatin formation based on a simple polymerization model. (This work was inspired by a derivation of cytoskeletal polymers in "Physical Biology of the Cell" by Phillips, Kondev, and Theriot, which is not yet published.)

If we think of formation of heterochromatin as similar to the assembly of a protein polymer, we can write a set of reactions starting from empty DNA (H0) and LexA-Sir2 (L) initially binding to form an initiation complex. Then addition of S molecules increases the length of the heterochromatin "polymer":

where S denotes the components involved in heterochromatin elongation (the pool of LexA-Sir2 plus endogenous Sir2).

At any time t, the probability of having a heterochromatin domain of length n is given by

These probabilities vary with time, so we can write a set of differential equations describing the mass action kinetics of formation/loss of polymers of a specific length:

Now, we can add in the equations describing the rest of the synthetic heterochromatin-based toggle circuit and implement the model in Matlab to observe its behavior:

The first equation above describes the transcriptional repression leg of the switch, e.g. Gal80 represses the expression of LexA-Sir2. We have added an additional point of control here by including galactose as a possible input to "flip" the switch through repressing the transcriptional repression. The second equation describes the silencing by heterochromatin, where we are making the assumption that once the expected length of heterochromatin (as calculated from the probability equations above) is greater than a certain threshold length, the Gal80 gene is completely silenced and is no longer being expressed.

These differential equations can be solved in Matlab. Below, we plot the concentrations of L and G (the two genes involved in the toggle switch) as a function of time.

| Figure 3: Time behavior of toggle switch circuit using heterochromatin polymerization model. The system starts in a high Gal80/low LexA state. Upon addition of galactose, the toggle switch is flipped to a high LexA/low Gal80 state. |

In the plot above, we can see that initially, the system is set to a high Gal80/low LexA state. When we add the input galactose which represses the repression of Gal80 on LexA-Sir2, the system starts expressing LexA-Sir2 and eventually, the toggle switch is flipped to and remains in a state with high LexA/low Gal80. So, we've made a toggle switch in silico!

Finally, we wanted to investigate whether we can observe a higher robustness with respect to parameter values in the heterochromatin-based toggle versus a transcription-based toggle. Remember that the heterochromatin-based toggle has an inherently high cooperativity and our earlier results (Figure 1) suggested that such a system should be able to achieve bistability over a larger region of parameter space than a transcription-based toggle, which typically has a much lower cooperativity.

A simple way to test this prediction is to compare the polymerization model and the Gardner-Collins model by varying parameters common to both models, e.g. the promoter strengths and the initial concentration of G. Note that in this comparison and similar to the analysis in Figure 1, we assume cooperativity on only one leg of the toggle switch. For the heterochromatin-based circuit, this is built into the formulation of the polymerization model and we add in no additional cooperativity constants. For the transcription-based circuit of Gardner-Collins, we set beta to 1 and gamma to a value between 2-4.

Then, for each particular set of parameters, we solve the differential equations to obtain the dynamic behavior of each system. To visualize the results, we take the ratio of the L concentration over the G concentration and draw as a heatmap.

| Figure 4: Robustness comparison between a heterochromatin-based toggle switch using the polymerization model (a), a transcription-based toggle switch using the Gardner-Collins model with gamma=2 (b), and one with gamma=4 (c). Colors are determined by taking the ratio between the concentration of L versus the concentration of G. Black arrows indicate sets of parameters resulting in toggling behavior. |

In the above two figures, each row corresponds to the time behavior of the system for a particular set of parameters with the color determined by the ratio of L over G. Thus, a system which can function as a toggle switch should start off and maintain a blue state (corresponding to G > L) until the addition of galactose (first white line). After the withdrawal of galactose (second white line), the system should be able to maintain a red state (L > G).

The initial comparison performed above uses a limited number of parameter values and thus, represents a very coarse sampling of parameter space. Nonetheless, we are beginning to see that the heterochromatin-based circuit is able to achieve bistability over a larger region of parameter space compared to the transcription-based one. Future work should map out the parameter space in more detail.

Summary

In the modeling portion of our iGEM project, we investigated different ways to model a synthetic toggle switch circuit based on heterochromatin. Using a well-established model of a transcription-based toggle circuit and modifying it to account for heterochromatin formation, we first showed that bistability can be more easily achieved in circuits with very high effective cooperativity. Next, we constructed a more mechanistic model of heterochromatin formation using the idea of nucleation and polymerization and showed that such a system can display the high effective cooperativity required for bistable behavior. This model performs as a toggle switch and does so over a larger range of parameter values, as compared to a transcription-based circuit.

Our modeling results, in combination with those from experiments, have shown that heterochromatin formation and the resulting silencing of DNA is able to achieve much higher effective cooperativity than traditional transcriptional regulation. This feature of heterochromatin allows us to implement 'memory' in a synthetic circuit and will no doubt prove useful to synthetic biologists as we begin to think about the construction of other complex systems.

| Home | The Team | The Project | Parts Submitted to the Registry | Modeling | Human Practices | Notebooks |

|---|

"

"