Team:Caltech

From 2008.igem.org

Caltechigem (Talk | contribs) |

Caltechigem (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

===Probiotic bacteria and other natural examples=== | ===Probiotic bacteria and other natural examples=== | ||

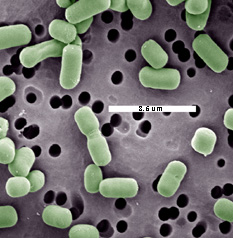

[[Image:Lacbr.jpg|thumb|left|Electron micrograph of ''Lactobacillus brevis'', a probiotic lactic acid bacterium]] | [[Image:Lacbr.jpg|thumb|left|Electron micrograph of ''Lactobacillus brevis'', a probiotic lactic acid bacterium]] | ||

| - | Most of the bacteria in our gut have yet to be characterized because they are difficult to culture, owing to their sensitivity to oxygen. However, several species are known. Many bacterial laboratory strains are derived from the well-known ''Escherichia coli'' (a non-pathogenic type), which is normally present in the large intestine. Because of its use in research, ''E. coli'' is the most well characterized bacteria to date. Another bacteria, ''Bacteroides fragilis'', plays an important role in proper development of the immune system and in controlling intestinal inflammation. Specifically, ''B. fragilis'' produces a starch called polysacharride A. In mice that had been raised in a sterile environment since birth (the intestinal track is initially sterile at birth and requires outside sources of bacteria to populate it), the immune system had less than normal levels of CD4+ killer T cells, a necessary white blood cell to battle infections. However the CD4+ levels returned to normal when the mice were raised again in a sterile environment, except for the presence of ''B. fragilis''. Polysaccharide A alone, not the mere presence of Bacteroides fragilis, was responsible for the improvement, since mice raised with ''B. fragilis'' that could not produce polysaccharide A showed the same levels of CD4+ cell as the sterile mice<sup>2</sup>. | + | Most of the bacteria in our gut have yet to be characterized because they are difficult to culture, owing to their sensitivity to oxygen. However, several species are known. Many bacterial laboratory strains are derived from the well-known ''Escherichia coli'' (a non-pathogenic type), which is normally present in the large intestine. Because of its use in research, ''E. coli'' is the most well characterized bacteria to date. Another bacteria, ''Bacteroides fragilis'', plays an important role in proper development of the immune system and in controlling intestinal inflammation. Specifically, ''B. fragilis'' produces a starch called polysacharride A. In mice that had been raised in a sterile environment since birth (the intestinal track is initially sterile at birth and requires outside sources of bacteria to populate it), the immune system had less than normal levels of CD4+ killer T cells, a necessary white blood cell to battle infections. However, the CD4+ levels returned to normal when the mice were raised again in a sterile environment, except for the presence of ''B. fragilis''. Polysaccharide A alone, not the mere presence of Bacteroides fragilis, was responsible for the improvement, since mice raised with ''B. fragilis'' that could not produce polysaccharide A showed the same levels of CD4+ cell as the sterile mice<sup>2</sup>. |

{{clear}} | {{clear}} | ||

Several bacterial species can cause disease in humans by infecting the gut. ''E. coli'' is commonly associated with food poisoning. ''Salmonela enterica'' is responsible for typhoid fever. ''Campylobacter jejuni'' and ''Shigella'' can cause bowl inflammation, diarrhea and dysentery. Cholera is caused by ''Vibrio cholerae'', which infected around 230,000 people and caused 6,300 deaths in 2006, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)[http://www.who.int/wer/2007/wer8231.pdf]. These pathogens typically cause illness in otherwise healthy people. There are other, more opportunistic bacteria, which infect people in hospital setting who are otherwise sick or undergoing treatment that puts them at greater risk for infection of their intestinal track. Paradoxically, the treatment of one pathogen with antibiotics can make that same patient more susceptible to infection of their gut by opportunistic pathogens. It is thought that the right balance of natural gut flora prevent these opportunistic pathogens from colonizing the colon<sup>3</sup>. | Several bacterial species can cause disease in humans by infecting the gut. ''E. coli'' is commonly associated with food poisoning. ''Salmonela enterica'' is responsible for typhoid fever. ''Campylobacter jejuni'' and ''Shigella'' can cause bowl inflammation, diarrhea and dysentery. Cholera is caused by ''Vibrio cholerae'', which infected around 230,000 people and caused 6,300 deaths in 2006, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)[http://www.who.int/wer/2007/wer8231.pdf]. These pathogens typically cause illness in otherwise healthy people. There are other, more opportunistic bacteria, which infect people in hospital setting who are otherwise sick or undergoing treatment that puts them at greater risk for infection of their intestinal track. Paradoxically, the treatment of one pathogen with antibiotics can make that same patient more susceptible to infection of their gut by opportunistic pathogens. It is thought that the right balance of natural gut flora prevent these opportunistic pathogens from colonizing the colon<sup>3</sup>. | ||

Revision as of 06:19, 25 October 2008

|

People

|

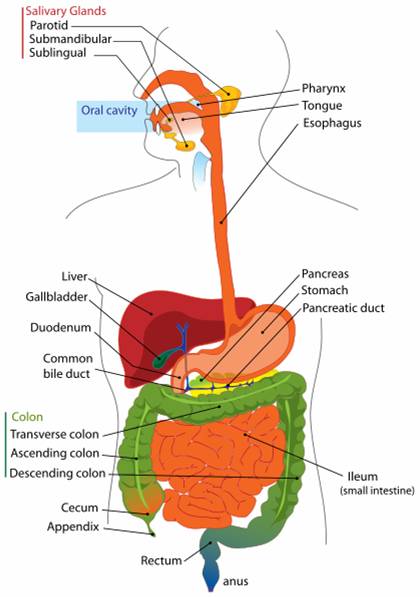

Engineering multi-functional probiotic bacteriaThe human gut houses a diverse collection of microorganisms, with important implications for the health and welfare of the host. We aim to engineer a member of this microbial community to provide innovative medical treatments. Our work focuses on four main areas: (1) pathogen defense either by expression of pathogen-specific bacteriophage or by targeted bursts of reactive oxygen species; (2) prevention of birth defects by folate over-expression and delivery; (3) treatment of lactose intolerance by cleaving lactose to allow absorption in the large intestine; and (4) regulation of these three treatment functions to produce renewable subpopulations specialized for each function. Our research demonstrates that synthetic biology techniques can be used to modify naturally occurring microbial communities for applications in biomedicine and biotechnology. Why engineer gut microbes?The large intestine: an ideal bioreactorThe human intestinal track is a perfect environment for bacteria. It is a 37°C mobile incubator with a constant stream of food. While bacteria are present in all parts of the intestinal track downstream of the stomach, the majority of those bacteria reside in the large intestine. There are approximately 1012 bacterial per mL in the large intestinal lumen, comprised of between 500-1000 different species of bacteria. Of these species, approximately 30 species compose 99% of all bacteria in the large intestine. Estimating there is roughly 100 mL of feces in the large intestine, all the bacteria in our gut outnumber all the cells in the human body 100 to 11. Probiotic bacteria and other natural examplesMost of the bacteria in our gut have yet to be characterized because they are difficult to culture, owing to their sensitivity to oxygen. However, several species are known. Many bacterial laboratory strains are derived from the well-known Escherichia coli (a non-pathogenic type), which is normally present in the large intestine. Because of its use in research, E. coli is the most well characterized bacteria to date. Another bacteria, Bacteroides fragilis, plays an important role in proper development of the immune system and in controlling intestinal inflammation. Specifically, B. fragilis produces a starch called polysacharride A. In mice that had been raised in a sterile environment since birth (the intestinal track is initially sterile at birth and requires outside sources of bacteria to populate it), the immune system had less than normal levels of CD4+ killer T cells, a necessary white blood cell to battle infections. However, the CD4+ levels returned to normal when the mice were raised again in a sterile environment, except for the presence of B. fragilis. Polysaccharide A alone, not the mere presence of Bacteroides fragilis, was responsible for the improvement, since mice raised with B. fragilis that could not produce polysaccharide A showed the same levels of CD4+ cell as the sterile mice2. Several bacterial species can cause disease in humans by infecting the gut. E. coli is commonly associated with food poisoning. Salmonela enterica is responsible for typhoid fever. Campylobacter jejuni and Shigella can cause bowl inflammation, diarrhea and dysentery. Cholera is caused by Vibrio cholerae, which infected around 230,000 people and caused 6,300 deaths in 2006, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)[http://www.who.int/wer/2007/wer8231.pdf]. These pathogens typically cause illness in otherwise healthy people. There are other, more opportunistic bacteria, which infect people in hospital setting who are otherwise sick or undergoing treatment that puts them at greater risk for infection of their intestinal track. Paradoxically, the treatment of one pathogen with antibiotics can make that same patient more susceptible to infection of their gut by opportunistic pathogens. It is thought that the right balance of natural gut flora prevent these opportunistic pathogens from colonizing the colon3. As a further example, humans cannot produce Vitamin K, an important cofactor in blood clotting. Instead, the vitamin is provided by various species of the gut microbiota, which collectively produce more than 30 times the vitamin K recommended daily allowance4.

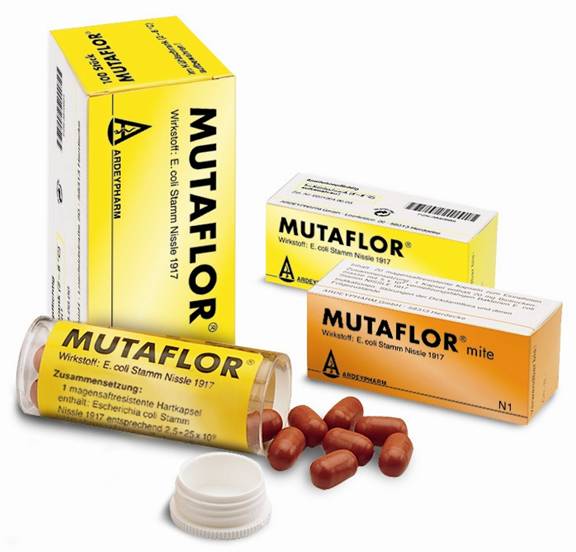

Nissle 1917: Probiotic, commercially available E. coliNissle 1917 is a commercially available[http://www.ardeypharm.de/en/] non-pathogenic, probiotic strain of E. coli. It has been successfully used to treat gastrointestinal disorders including colitis and intestinal bowel disease5 and shows little immunostimulatory activity6. Engineered versions of the Nissle 1917 strain have been developed as anti-HIV7 and anti-cholera8 agents. The ability of Nissle 1917 to efficiently colonize the gut without provoking an inflammatory response makes it an ideal chassis for in situ applications in biomedicine and biotechnology. For more details, please see our project page. References

|

"

"