Team:Hawaii/Project/Part A

From 2008.igem.org

Normanwang (Talk | contribs) |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Broad Host Range Mobilizable BioBrick Vector== | ==Broad Host Range Mobilizable BioBrick Vector== | ||

| - | === | + | === Objective === |

| - | + | ||

| - | RSF1010 derived | + | To compartmentalize an RSF1010 derived plasmid, pRL1383a, into biobricks. The resulting biobricks, when inserted into a biobrick base vector are capable of transferring genetic elements through conjugation. The ''aadA'' gene, from the omega interposon inferring Spectinomycin and Streptomycin resistance, will be converted to biobrick format and used for selection purposes in this construct. |

| - | + | The bulky mobilization genes which are 2612 base pairs in length will be replaced with the origin of transfer region of RP4, a segment of DNA which is only 99 base pairs, leaving the construct more compact. | |

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | === Introduction === | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | RSF1010 is a broad-host-range plasmid first described in 1974 (Guerry 1974), with its entire sequence and gene organization subsequently described in 1989 (Scholz 1989). It is a naturally occurring 8.6kb broad-host-range plasmid in the ''E. coli'' incompatibility group Q. The conjugative transfer and stable replication of this plasmid are possible due to the mob genes with the associated origin of transfer (oriT) and the rep genes with the associated origin of vegetative replication (oriV), respectively. | |

| + | RSF1010 derived plasmids which include the oriV and associated Rep proteins are stably maintained in ''Pseudomonas'' (Bagdasarian 1981), ''Caulobacter'' (Umelo-Njaka et al. 2001), ''Erwinia'', and ''Serratia'' (Leemans 1987). In addition, RSF1010 derived plasmids including the oriV, oriT and its associated ''rep'' and ''mob'' genes are transferred by conjugation to at least four cyanobacteria strains (Mermet-Bouvier 1993). These cyanobacteria strains include ''Synechocystis'' PCC6803 and PCC6714 and ''Synechococcus'' PCC7942 and PCC6301. | ||

| + | A number of RSF1010 derived plasmids have been constructed due to the utility of this broad-host-range plasmid. For example, pSB2A, containing a 5.6kb RSF1010 derived region including the necessary mobilization and replication regions, can be transferred through conjugation to and stably maintained in ''Synechocystis'' PCC6803, PCC6714, and ''Synechococcus'' PCC7942 and PCC6301 (Marraccini 1993). | ||

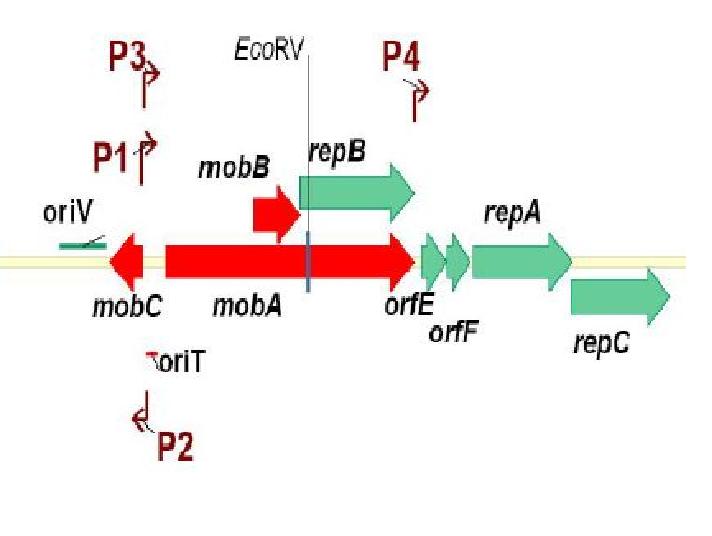

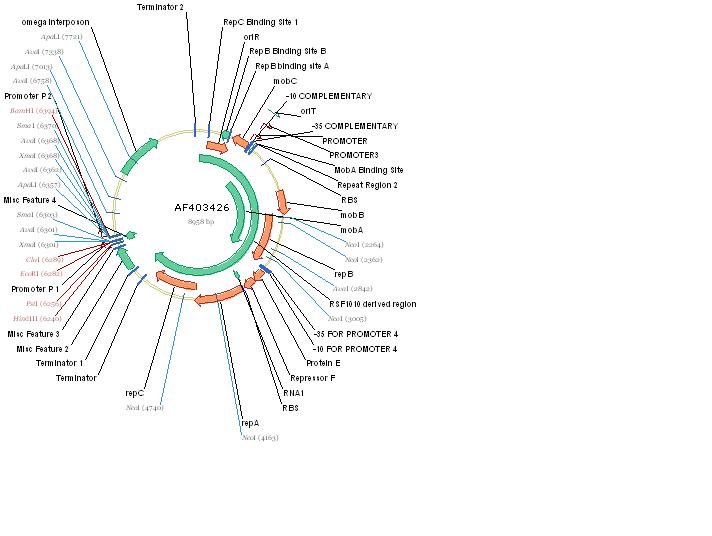

| + | The RSF1010 plasmid used in this study, pRL1383a (Figure 1) was constructed for use in genomic studies of the diazotrophic, multicellular cyanobacterium ''Anabaena'' PCC 7120. This plasmid contains the ''mob'' and ''rep'' regions necessary for conjugation and autonomous replication, respectively. Additionally this vector is made resistant to Streptomycin and Spectinomycin due to the presence of the ''aadA'' gene (Wolk 2007). | ||

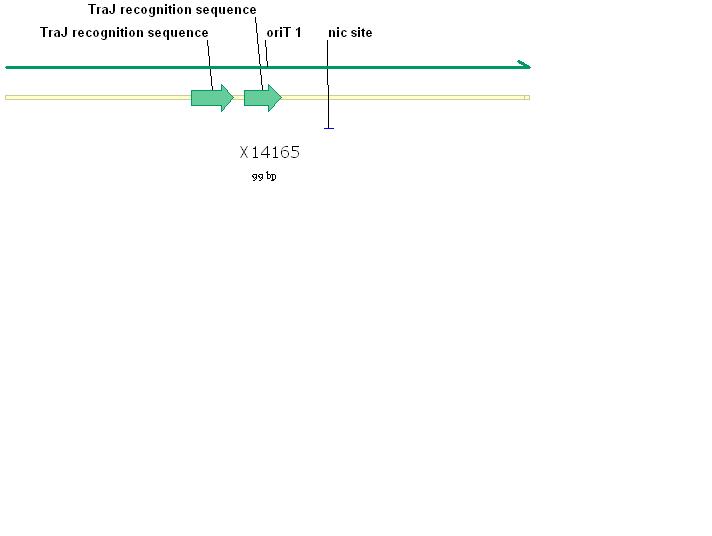

| + | This plasmid can be mobilized by the ''E. coli'' derived self-transmissible plasmid RP4. Mobilization genes are not necessary for transfer of a mobilizable plasmid if the self-transmissible plasmid and the mobilizable plasmid share a common origin of transfer (Snyder and Champness 2007). The origin of transfer for RP4 is 99 base pairs and contains binding sites for transfer proteins encoded by RP4 (Figure 2). | ||

| - | + | [[Image:pRL1383a.jpg|thumb|Figure 1: pRL1383a is a mobilizable, broad-host-range vector derived from RSF1010. Included in this plasmid are the genes required for autonomous replication (repA/B/C), their promoters and the origin of vegetative replication, which is the site of protein binding, and relaxation of the DNA. Also included are the genes required for mobilization (mobA/B/C) as well as their associated promoters and the origin of transfer. A selectable marker is also included: the omega interposon.]] | |

| + | |||

| - | + | [[Image:RP4_relaxation_region.jpg|thumb|left|Figure 2: Plasmid RP4 oriT relaxation region. This region features the TraJ recognition sequence which is a nick site.]] | |

| - | + | [[Image:mob_region_pRL1383a.jpg|thumb|right| Figure 3: The mobilization region of pRL1383a.]] | |

| - | + | <strong>Genetic Elements Required for Conjugation:</strong> | |

| + | <strong>Genetic Elements Required for Autonomous Replication:</strong> | ||

| + | pRL1383a is equipped with an origin of replication and the corresponding replication proteins which facilitate autonomous replication. There are three replication proteins. Two of these proteins, RepA, a helicase, and RepC, an oriV binding protein are found on the same operon (''E/F/repA/repC'') which also includes a hypothetical protein, and an auto-regulatory protein: repressor F. Regulation at the level of translation is also found in this operon in that a functional RepC requires the upstream translation of RepA (Scholtz 1988). A G+C rich region with dyad-symmetry followed by an A+T rich region is located at the end of the operon (''E/F/repA/repC'') which may be a rho-independent transcription terminator (Scholtz 1988). When pRL1383a was designed, an additional terminator was placed downstream of the (''E/F/repA/repC'') operon (Wolk 2007). | ||

| + | RepB’, a functional subunit of the MobA/RepB dimer (Katashkina 2007, Scholtz 1988) acts as a primase during vegetative replication. RepB’ is under the same promoter as MobA and the product is a dimer in which the N-terminal domain is active in mobilization and the C-terminal domain (RepB’) is functional in primer synthesis at the origin of replication. In the past, the isolation of RepB’, in an attempt to make a non-mobilizable mutant of RSF1010, required that ''repB’'' be put under another promoter, P<sub>lacUV5</sub>lacI, for successful replicative capability (Katashkina 2007). The choice of promoters is important because plasmid copy number is largely determined by the auto-regulatory function of mobilization proteins MobC and MobA, so the promoter chosen must also have some regulatory capabilities (Katashkina 2007). To emphasize the regulatory function of this promoter, when ''lacI'' was removed from the promoter, the copy number of the plasmid tripled (Katashkina 2007). | ||

| + | <strong>Antibiotic Selection:</strong> | ||

| + | The omega interposon is an insertional mutagenesis tool containing the ''aadA'' gene from R1001.1 which infers Spectinomycin and Streptomycin resistance. Flanking ''aadA'' are transcriptional termination sites of the T4 gene 32 so that transcription cannot be achieved through the omega interposon from either side. To avoid polypeptide synthesis at the position of the omega interposon, synthetic translational stop codons were also included. Flanking this feature are two polylinkers (Prentki 1983). | ||

| + | pRL1383a was constructed not for insertional mutagenesis but for expression of genes on an autonomously replicating plasmid, therefore the version of the omega interposon included in pRL1383a only includes the ''aadA'' gene, leaving out the tools necessary for insertional mutagenesis (Wolk 2007). The ''aadA'' gene is desirable for this purpose because it infers resistance to two antibiotics, making the chance for spontaneous mutants decrease dramatically. | ||

| + | <strong>The Biobrick Base Vector:</strong> | ||

| + | A biobrick base vector houses several advantageous features (Shetty 2008) including the biobrick insertion site, a positive selection marker, primer verification sites, as well as additional features. The compartmentalization of pRL1383a into biobricks will allow us to clone our units into the biobrick base vector (Bba_I51020) creating a plasmid which combines the broad-host-range features of pRL1383a with the standardized features of the biobrick base vector. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:omega_interposon.jpg|thumb| Figure 4: The omega interposon where a promoter region (-35 and -10) lies upstream of the aadA gene which is flanked by two transcription termination sites (TT) additionally flanked by translation stop codons.]] | ||

| - | + | == Methods == | |

| - | + | Each of the aforementioned segments of pRL1383a will be isolated using PCR methods. These segments are selected based not only on function, but also on proximity. Therefore the arrangement will be in four segments which include the origin of vegetative Replication (oriV) and associated binding sites, the mobilization genes (''mobA/RepB'', ''mobC'', and ''mobB'') and associated promoters, the replication genes (''repB’'', ''repA'', and ''repC'') and associated promoters and regulatory proteins, except for the promoter regulating ''repB’'', which will require the addition of a promoter. The PlacI promoter (BBa_R0010), a constitutive promoter with high rates of transcription, regulated by the ''lacI'' coding region (BBa_C0012) will be used to regulate RepB’. The ''aadA'' region of the omega interposon will become a biobrick as well. Table 1 is a list of primers that will be used to this end. | |

| - | + | Table 1: A list of the primers used in the construction of a biobrick vector. | |

| + | Region Primer Primer Sequence Length G/C Tm Length 2 GC 2 Tm2 | ||

| + | aadA region Forward 5’-cctttctagatgagggaagcggtgatcg-3’ 19 bp 57.9% 59.4C 28 53.6% 65.7C | ||

| + | Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagcggccgctactagtattattatttgccgactaccttgg-3’ 20 bp 45% 55.4C 50 50% 74.8C | ||

| + | Ori R Forward 5’-cctttctagag-gaacccctgcaataactgtc-3’ 20 bp 50% 56.3C 31 48.4% 65.9C | ||

| + | Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtagctgaatgatcgaccgagac-3’ 20 bp 55% 58C 47 57.4% 76.4C | ||

| + | Mob | ||

| + | Proteins Forward 5’-cctttctagag-taa-tcagcccggctcatcc -3’ 16 bp 68.8% 58.5 30 53.3% 67C | ||

| + | Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtattattacatgctgaaatctggcc-3’ 17bp 52.9% 53C 50 50% 75.1C | ||

| + | Rep | ||

| + | Proteins Forward 5’- cctttctagatgaagaacgacaggactttgc-3’ 22 bp 45.5% 58.9 C 21 bp 45.2% 64.9C | ||

| + | Reverse 5’- aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtacctatggagctgtgcggca-3’ 19 bp 63.2% 62.2 C 46 bp 60.9% 78.6 C | ||

| - | + | The origin of transfer derived from RP1, having homologous DNA sequence to RP4 was synthetically constructed using a method developed by the Silver lab. Essentially the origin of transfer region was cut into six overlapping pieces (Table 2). The synthetic constructs will be overlapped in a reaction containing a polynucleotide kinase. The resulting construct will have XbaI overhangs at the 5’ end and NotI and SpeI sites at the 3’ end to facilitate ligation into a biobrick vector. | |

| - | + | Table 2: A list of overlapping oligonucleotides used for the construction of RP4’s origin of transfer. | |

| - | + | Forward: | |

| + | ctagaggaataagggacagtgaagaaggaacacccgctcgcgggtgggcc | ||

| + | tacttcacctatcctgcccggctgacgccgttggatacaccaaggaaagt | ||

| + | ctacatactagtagcggccgctgca | ||

| + | Complement: cttattccctgtcacttcttccttgtgggcgagcgcccacccggatgaag | ||

| + | tggataggacgggccgactgcggcaacctatgtggttcctttcagatgt | ||

| + | Oligo1 ctagaggaataagggacagtgaagaaggaacacccgctcg | ||

| + | Oligo2 cgggtgggcctacttcacctatcctgcccggctgacgccg | ||

| + | Oligo3 ttggatacaccaaggaaagtctacatactagtagcggccgctgca | ||

| + | Oligo4 GCGGCCGCTACTAGTAtgtagactttccttggtg | ||

| + | Oligo5 tatccaacggcgtcagccgggcaggataggtgaagtaggcc | ||

| + | Oligo6 cacccgcgagcgggtgttccttcttcactgtcccttattcCT | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | == Conclusion == | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | == | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | Conclusions: | |

| - | + | This plasmid can be made available in biobrick format and furthermore in a smaller construct rendering it more accessible to manipulation and smaller so that useful elements can be added in greater abundance. | |

| - | + | Literature Sited: | |

| - | + | • Molecular Genetics of Bacteria, 3rd ed., Snyder and Champness (2007) ASM Press | |

| - | + | • Scholtz “Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010,” 1988, Gene 75 (1989) 217-288. | |

| - | + | • Mermet-Bouvier (1993), “Transfer and replication of RSF1010 derived plasmids in several cyanobacteria in the genera of Synechocystis and Synechococcus,” Current Microbiology 27, 323-327. | |

| - | + | • Shetty, Reshma, “Engineering BioBrick vectors from BioBrick parts.” Journal of Biological Engineering 2008, 2:5 | |

| - | + | • Prentki P, Krisch HM, “In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment,”Gene. 1984 Sep;29(3):303-13. | |

| - | + | • Chauvat, “A host-vector system for gene cloning in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803,” Mol. Gen. Genet (1986) 204:185-191. | |

| - | + | • Katashkina JI, “Construction of stably maintained non-mobilizable derivatives of RSF1010 lacking all known elements essential for mobilization.” BMC Biotechnol 2007 Nov 21; 7 80. | |

| - | + | • Phillips, Ira & Pamela Silver, “A New Biobrick Assembly Strategy Designed for Facile Protein Engineering,” http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/32535. | |

| - | + | • Silver Lab (http://openwetware.org/wiki/Silver:_Oligonucleotide_Inserts) | |

| - | + | • Guerry, van Embden, & Falkow 1974 | |

| - | + | • Bagdasarian et al. 1981 | |

| - | + | • Wolk et al. “Paired cloning vectors for complementation of mutations in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120.” Archives of Microbiology 188, 551-563 (2007). | |

| - | + | • Vector NTI | |

Revision as of 19:56, 2 July 2008

Contents |

Broad Host Range Mobilizable BioBrick Vector

Objective

To compartmentalize an RSF1010 derived plasmid, pRL1383a, into biobricks. The resulting biobricks, when inserted into a biobrick base vector are capable of transferring genetic elements through conjugation. The aadA gene, from the omega interposon inferring Spectinomycin and Streptomycin resistance, will be converted to biobrick format and used for selection purposes in this construct.

The bulky mobilization genes which are 2612 base pairs in length will be replaced with the origin of transfer region of RP4, a segment of DNA which is only 99 base pairs, leaving the construct more compact.

Introduction

RSF1010 is a broad-host-range plasmid first described in 1974 (Guerry 1974), with its entire sequence and gene organization subsequently described in 1989 (Scholz 1989). It is a naturally occurring 8.6kb broad-host-range plasmid in the E. coli incompatibility group Q. The conjugative transfer and stable replication of this plasmid are possible due to the mob genes with the associated origin of transfer (oriT) and the rep genes with the associated origin of vegetative replication (oriV), respectively. RSF1010 derived plasmids which include the oriV and associated Rep proteins are stably maintained in Pseudomonas (Bagdasarian 1981), Caulobacter (Umelo-Njaka et al. 2001), Erwinia, and Serratia (Leemans 1987). In addition, RSF1010 derived plasmids including the oriV, oriT and its associated rep and mob genes are transferred by conjugation to at least four cyanobacteria strains (Mermet-Bouvier 1993). These cyanobacteria strains include Synechocystis PCC6803 and PCC6714 and Synechococcus PCC7942 and PCC6301.

A number of RSF1010 derived plasmids have been constructed due to the utility of this broad-host-range plasmid. For example, pSB2A, containing a 5.6kb RSF1010 derived region including the necessary mobilization and replication regions, can be transferred through conjugation to and stably maintained in Synechocystis PCC6803, PCC6714, and Synechococcus PCC7942 and PCC6301 (Marraccini 1993).

The RSF1010 plasmid used in this study, pRL1383a (Figure 1) was constructed for use in genomic studies of the diazotrophic, multicellular cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. This plasmid contains the mob and rep regions necessary for conjugation and autonomous replication, respectively. Additionally this vector is made resistant to Streptomycin and Spectinomycin due to the presence of the aadA gene (Wolk 2007). This plasmid can be mobilized by the E. coli derived self-transmissible plasmid RP4. Mobilization genes are not necessary for transfer of a mobilizable plasmid if the self-transmissible plasmid and the mobilizable plasmid share a common origin of transfer (Snyder and Champness 2007). The origin of transfer for RP4 is 99 base pairs and contains binding sites for transfer proteins encoded by RP4 (Figure 2).

Genetic Elements Required for Conjugation: Genetic Elements Required for Autonomous Replication: pRL1383a is equipped with an origin of replication and the corresponding replication proteins which facilitate autonomous replication. There are three replication proteins. Two of these proteins, RepA, a helicase, and RepC, an oriV binding protein are found on the same operon (E/F/repA/repC) which also includes a hypothetical protein, and an auto-regulatory protein: repressor F. Regulation at the level of translation is also found in this operon in that a functional RepC requires the upstream translation of RepA (Scholtz 1988). A G+C rich region with dyad-symmetry followed by an A+T rich region is located at the end of the operon (E/F/repA/repC) which may be a rho-independent transcription terminator (Scholtz 1988). When pRL1383a was designed, an additional terminator was placed downstream of the (E/F/repA/repC) operon (Wolk 2007).

RepB’, a functional subunit of the MobA/RepB dimer (Katashkina 2007, Scholtz 1988) acts as a primase during vegetative replication. RepB’ is under the same promoter as MobA and the product is a dimer in which the N-terminal domain is active in mobilization and the C-terminal domain (RepB’) is functional in primer synthesis at the origin of replication. In the past, the isolation of RepB’, in an attempt to make a non-mobilizable mutant of RSF1010, required that repB’ be put under another promoter, PlacUV5lacI, for successful replicative capability (Katashkina 2007). The choice of promoters is important because plasmid copy number is largely determined by the auto-regulatory function of mobilization proteins MobC and MobA, so the promoter chosen must also have some regulatory capabilities (Katashkina 2007). To emphasize the regulatory function of this promoter, when lacI was removed from the promoter, the copy number of the plasmid tripled (Katashkina 2007).

Antibiotic Selection: The omega interposon is an insertional mutagenesis tool containing the aadA gene from R1001.1 which infers Spectinomycin and Streptomycin resistance. Flanking aadA are transcriptional termination sites of the T4 gene 32 so that transcription cannot be achieved through the omega interposon from either side. To avoid polypeptide synthesis at the position of the omega interposon, synthetic translational stop codons were also included. Flanking this feature are two polylinkers (Prentki 1983). pRL1383a was constructed not for insertional mutagenesis but for expression of genes on an autonomously replicating plasmid, therefore the version of the omega interposon included in pRL1383a only includes the aadA gene, leaving out the tools necessary for insertional mutagenesis (Wolk 2007). The aadA gene is desirable for this purpose because it infers resistance to two antibiotics, making the chance for spontaneous mutants decrease dramatically. The Biobrick Base Vector:

A biobrick base vector houses several advantageous features (Shetty 2008) including the biobrick insertion site, a positive selection marker, primer verification sites, as well as additional features. The compartmentalization of pRL1383a into biobricks will allow us to clone our units into the biobrick base vector (Bba_I51020) creating a plasmid which combines the broad-host-range features of pRL1383a with the standardized features of the biobrick base vector.

Methods

Each of the aforementioned segments of pRL1383a will be isolated using PCR methods. These segments are selected based not only on function, but also on proximity. Therefore the arrangement will be in four segments which include the origin of vegetative Replication (oriV) and associated binding sites, the mobilization genes (mobA/RepB, mobC, and mobB) and associated promoters, the replication genes (repB’, repA, and repC) and associated promoters and regulatory proteins, except for the promoter regulating repB’, which will require the addition of a promoter. The PlacI promoter (BBa_R0010), a constitutive promoter with high rates of transcription, regulated by the lacI coding region (BBa_C0012) will be used to regulate RepB’. The aadA region of the omega interposon will become a biobrick as well. Table 1 is a list of primers that will be used to this end.

Table 1: A list of the primers used in the construction of a biobrick vector. Region Primer Primer Sequence Length G/C Tm Length 2 GC 2 Tm2 aadA region Forward 5’-cctttctagatgagggaagcggtgatcg-3’ 19 bp 57.9% 59.4C 28 53.6% 65.7C Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagcggccgctactagtattattatttgccgactaccttgg-3’ 20 bp 45% 55.4C 50 50% 74.8C Ori R Forward 5’-cctttctagag-gaacccctgcaataactgtc-3’ 20 bp 50% 56.3C 31 48.4% 65.9C Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtagctgaatgatcgaccgagac-3’ 20 bp 55% 58C 47 57.4% 76.4C Mob Proteins Forward 5’-cctttctagag-taa-tcagcccggctcatcc -3’ 16 bp 68.8% 58.5 30 53.3% 67C Reverse 5’-aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtattattacatgctgaaatctggcc-3’ 17bp 52.9% 53C 50 50% 75.1C Rep Proteins Forward 5’- cctttctagatgaagaacgacaggactttgc-3’ 22 bp 45.5% 58.9 C 21 bp 45.2% 64.9C Reverse 5’- aaggctgcagagcggccgctactagtacctatggagctgtgcggca-3’ 19 bp 63.2% 62.2 C 46 bp 60.9% 78.6 C

The origin of transfer derived from RP1, having homologous DNA sequence to RP4 was synthetically constructed using a method developed by the Silver lab. Essentially the origin of transfer region was cut into six overlapping pieces (Table 2). The synthetic constructs will be overlapped in a reaction containing a polynucleotide kinase. The resulting construct will have XbaI overhangs at the 5’ end and NotI and SpeI sites at the 3’ end to facilitate ligation into a biobrick vector.

Table 2: A list of overlapping oligonucleotides used for the construction of RP4’s origin of transfer.

Forward: ctagaggaataagggacagtgaagaaggaacacccgctcgcgggtgggcc tacttcacctatcctgcccggctgacgccgttggatacaccaaggaaagt ctacatactagtagcggccgctgca Complement: cttattccctgtcacttcttccttgtgggcgagcgcccacccggatgaag tggataggacgggccgactgcggcaacctatgtggttcctttcagatgt Oligo1 ctagaggaataagggacagtgaagaaggaacacccgctcg Oligo2 cgggtgggcctacttcacctatcctgcccggctgacgccg Oligo3 ttggatacaccaaggaaagtctacatactagtagcggccgctgca Oligo4 GCGGCCGCTACTAGTAtgtagactttccttggtg Oligo5 tatccaacggcgtcagccgggcaggataggtgaagtaggcc Oligo6 cacccgcgagcgggtgttccttcttcactgtcccttattcCT

Conclusion

Conclusions: This plasmid can be made available in biobrick format and furthermore in a smaller construct rendering it more accessible to manipulation and smaller so that useful elements can be added in greater abundance. Literature Sited: • Molecular Genetics of Bacteria, 3rd ed., Snyder and Champness (2007) ASM Press • Scholtz “Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010,” 1988, Gene 75 (1989) 217-288. • Mermet-Bouvier (1993), “Transfer and replication of RSF1010 derived plasmids in several cyanobacteria in the genera of Synechocystis and Synechococcus,” Current Microbiology 27, 323-327. • Shetty, Reshma, “Engineering BioBrick vectors from BioBrick parts.” Journal of Biological Engineering 2008, 2:5 • Prentki P, Krisch HM, “In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment,”Gene. 1984 Sep;29(3):303-13. • Chauvat, “A host-vector system for gene cloning in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803,” Mol. Gen. Genet (1986) 204:185-191. • Katashkina JI, “Construction of stably maintained non-mobilizable derivatives of RSF1010 lacking all known elements essential for mobilization.” BMC Biotechnol 2007 Nov 21; 7 80. • Phillips, Ira & Pamela Silver, “A New Biobrick Assembly Strategy Designed for Facile Protein Engineering,” http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/32535. • Silver Lab (http://openwetware.org/wiki/Silver:_Oligonucleotide_Inserts) • Guerry, van Embden, & Falkow 1974 • Bagdasarian et al. 1981 • Wolk et al. “Paired cloning vectors for complementation of mutations in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120.” Archives of Microbiology 188, 551-563 (2007). • Vector NTI

"

"