Team:Caltech/Project/Vitamins

From 2008.igem.org

|

People

|

In vivo Folate Production

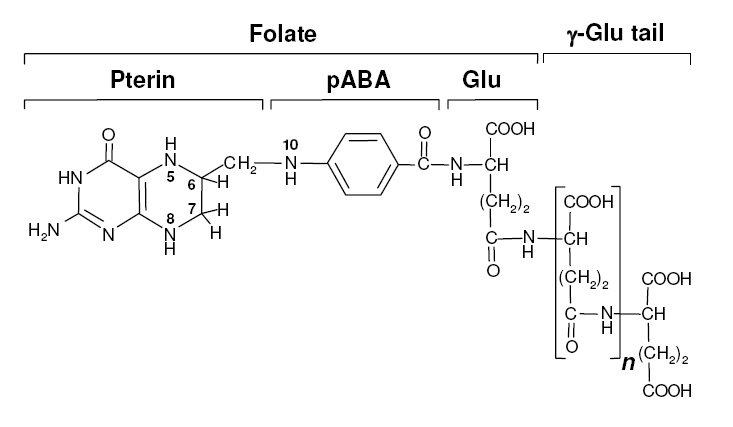

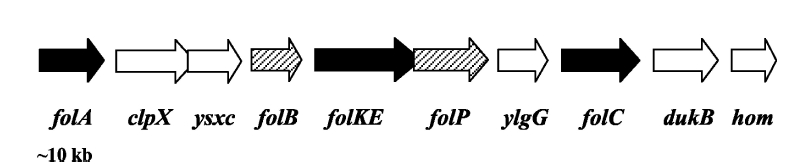

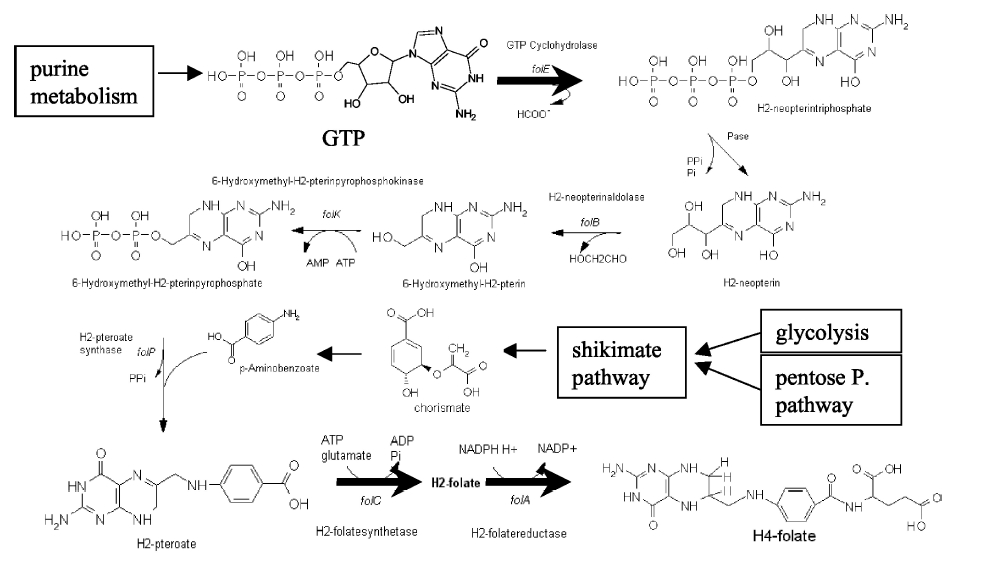

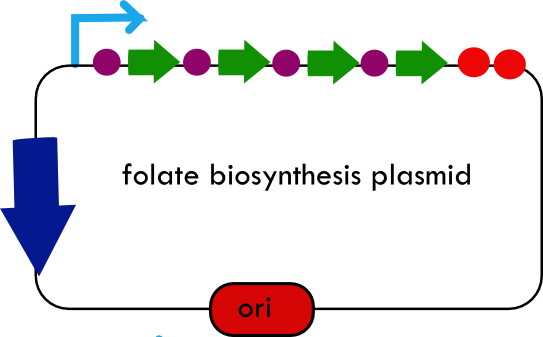

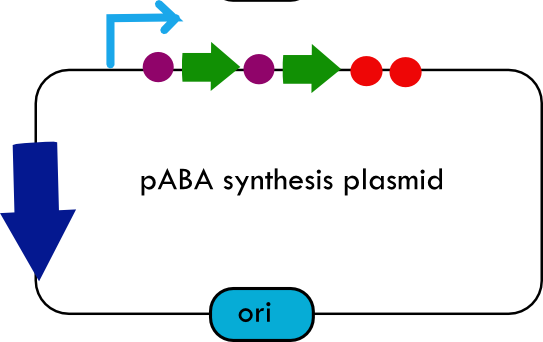

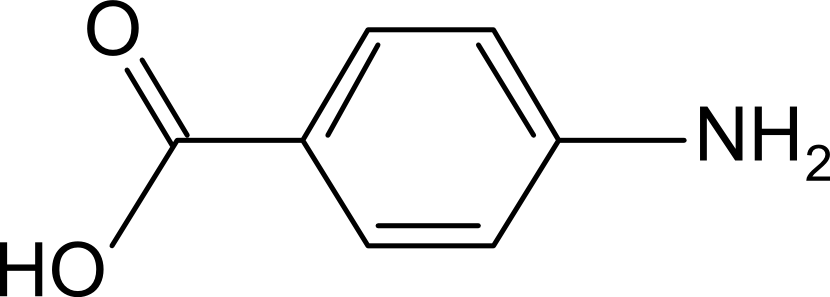

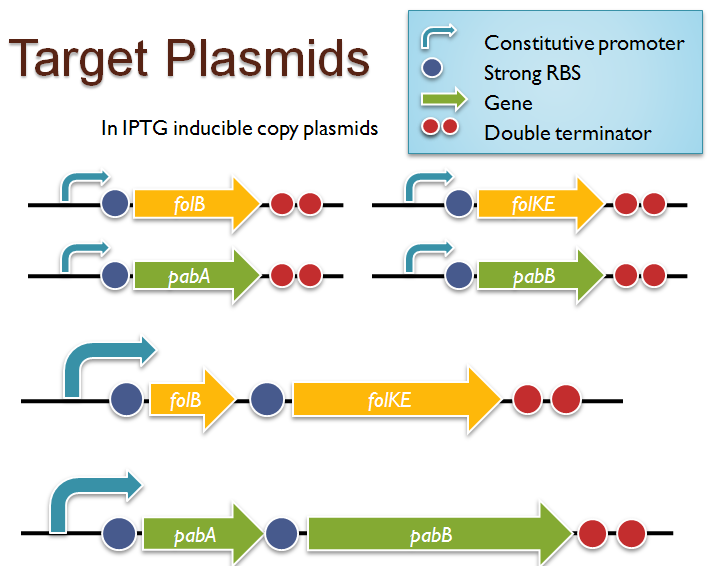

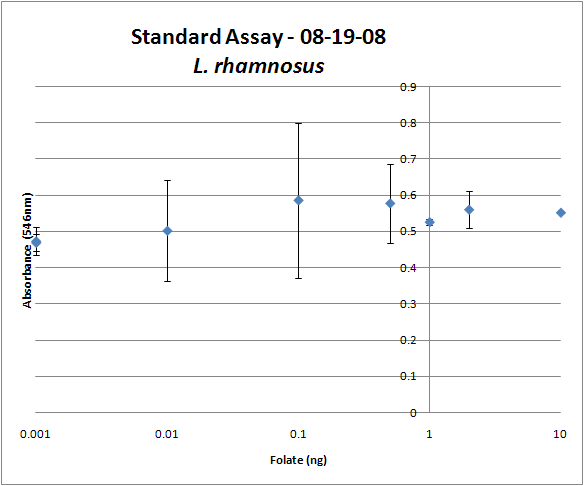

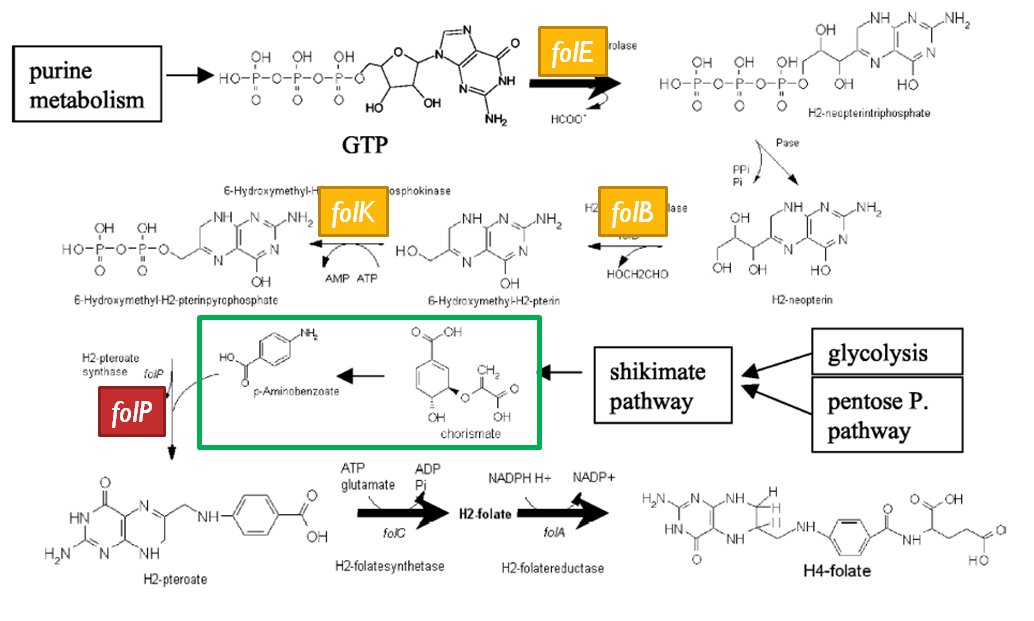

Background Information on FolateFolate, the generic term for the various forms of Vitamin B9, is an essential vitamin involved in single-carbon transfer reactions, which are important for many pathways including amino acid synthesis. Folate deficiencies in women can result in birth defects such as neural tube defects and other spinal cord malformations. As important as folate is, humans are unable to produce folate, and so must obtain it from eating foods such as green leafy vegetables or folate-fortified cereals. An engineered strain of bacteria that would constantly release folate into the gut would reduce the need to fortify breads and cereals with folate, as well as reduce folate-related birth defects in regions with little access to folate-containing foods. In addition to all the reasons stated above, folate is an ideal vitamin to be produced in the gut because, unlike many other vitamins, it has been shown to be absorbed in physiologically relevant quantities in the large intestine. Structurally, folate consists of three main parts: pteridine (derived from GTP), p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA, derived from chorismate), and a poly-glutamyl tail (derived from linking glutamate). Folate Biosynthesis PathwayAlthough folate is naturally produced in E. coli, the folate biosynthesis pathway in the bacteria Lactococcus lactis has been more heavily characterized and studied. In previous studies, this folate gene cluster has been successfully transformed into the folate-consuming bacteria L. gasseri, turning the bacteria into folate-producers. Using the folate gene cluster from L. lactis also offers the additional benefit of removing the operon from its natural regulatory context. There are six major enzymatic activities involved in folate synthesis, which, in L. lactis, are contained in five genes: folB, folKE, folP, folC, and folA. The first four, which we have chosen to focus on, are located in a gene cluster approximately 4.4kb long. We have chosen not to test overexpression of folA because it encodes for an enzyme which turns one form of folate (dihydrofolate) into another form of folate (tetrahydrofolate). Since our assay would detect both types of folate as part of the total folate production, folA was not a prime target for overexpression of folate. Our strategy is to clone the entire folate operon from the L.lactis genome and to transform the entire operon into E.coli. However, because we are unsure of whether or not the ribosomal binding sites (RBS) within the L.lactis operon would work in E.coli, we are also going to unpack the operon by cloning each of the four genes individually, placing them behind E.coli RBSs, and then recombine them into a single empty BioBricks™ plasmid. In addition to the main folate operon, we will also be experimenting with overexpression of the para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) synthesis pathway from chorismate. Wegkamp et al. have shown that in order to increase overall total levels of folate, both the pABA synthesis genes and certain folate production genes need to be overexpressed. The pABA pathway involves three enzymatic activities, pabA, pabB, and pabC – though in L.lactis, pabB is actually a bifunctional enzyme containing the activities for both pabB and pabC. System DesignThe overall system design for testing folate production in E. coli is to construct several plasmids: one for each individual gene, one for the folate biosynthesis pathway, and one for the PABA synthesis pathway. Each gene, or gene cluster, would be cloned in an inducible-copy plasmid, which would be low copy by default, but can be switched to high copy via the addition of Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)to the media. This will allow us to test overexpression of each plasmid separately. In addition, each plasmid contains a constitutive promoter, to ensure the constant production of folate. Folate Detection MethodsWe measured folate production, and thus the relative success of our engineering efforts, via a microbiological assay involving the folate-dependent strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus (ATCC 7469). The assay uses growth of the folate-dependent strain L. rhamnosus as an indicator of folate concentrations in the sample. The assay media specifically lacks folate, so folate becomes the limiting factor in the growth of L. rhamnosus, with the only possible source being the bacterial lysates of the engineered E. coli. In order to quantify the relative growth of the folate-dependent strain L. rhamnosus, a standard growth curve must first be characterized using known quantities of folic acid in assay media. Once the standard curve has been established, then experimental growth levels, as quantified by spectrophotometry, can be interpolated. Protocols are based off of BD Biosciences Folate Assay Medium datasheet {BD}. Growth was measured by taking the OD at 546nm. Further details are available on the folate microbiological assay protocol page. pABA Detection Methodspara-Aminobenzoic Acid (PABA) can be detected using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Using a 14 minute protocol, we were able to detect PABA peaks coming off a C18 column at 4.9 min. A standard curve was made by running a series of 1:3 PABA dilutions starting at a 10μg/ml concentration. The PABA for the standard curve was spiked into wild type E. coli cell lysate, which by itself did not show any detectable PABA peaks. Samples were run using the same HPLC protocol as the standards, and both lysate and supernatant were tested for PABA peaks. Again, details on the PABA detection method can be found on the para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) HPLC protocol page. ResultsModifications to System DesignWe were able to successfully extract and clone the following four genes: folB, folKE, pabA, and pabB. We aimed to create individual constructs of each gene in the IPTG inducible-copy plasmid pSB2K3, as well as constructs with the two folate genes combined and with the two PABA synthesis genes combined. However, we had issues cloning our genes into the pSB2K3 + B0015 terminator construct, and so switched to completing the constructs in the high copy plasmid pSB1AK3 + B0015 terminator. Our final constructs, shown on the right, are folB in pSB2K3, and folKE and pabA in pSB1AK3. We were unable to sequence confirm our folBKE and pabB constructs, and so unfortunately could not include their data. Previous studies on folate overexpression have shown that both folate synthesis and PABA synthesis genes need to be overexpressed simultaneously in order to increase total folate levels. Therefore, tests on folB and folKE were done with and without the addition of PABA during the E. coli inoculation; detection of higher folate levels on addition of PABA would indicate PABA as a limiting factor for folate production. We were unable to use PCR to extract several of the target genes: the entire folate gene cluster, folP, and folC. After analyzing the sequencing results of our other folate biosynthesis genes, we realized that the genetic sequences had several point mutations which were not `stop' codons. This indicated that we had a homologous, but not identical, genomic DNA than the one that we has used for PCR primer design. We believe that this homologous sequence could have resulted in too many differences between the primer and the genomic DNA, resulting in little to no binding. This may explain why we were unable to successfully extract folP, folC, and subsequently, the entire folate gene cluster (since folP and folC are the last two genes in the cluster) from the genomic DNA of L. lactis. The revised target constructs are shown .

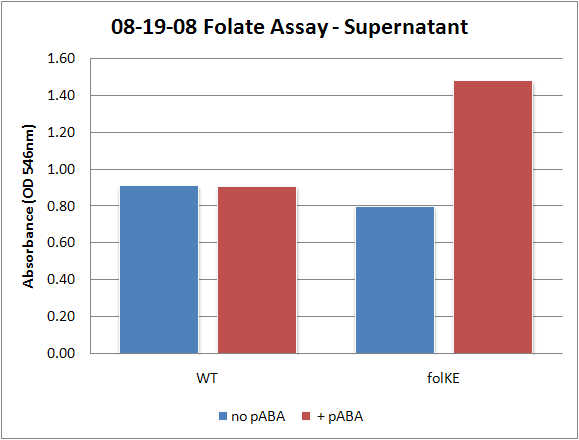

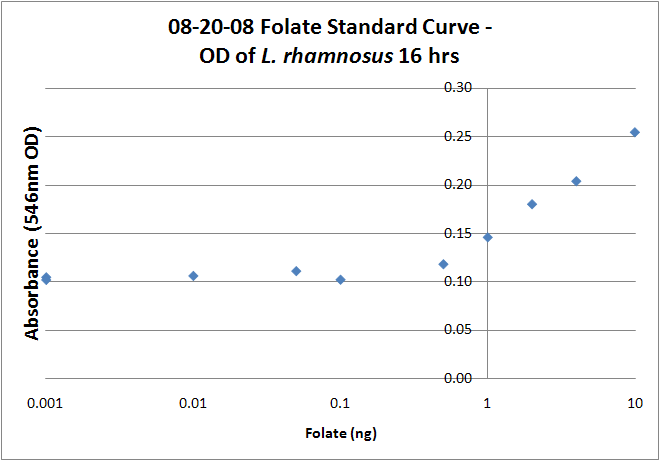

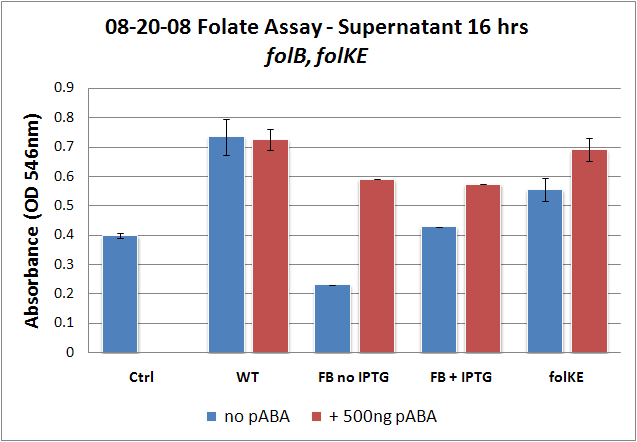

Folate Assay Results for folB AND folKEThe experimental setup included running a standard curve with known amounts of folic acid (0-10ng) simultaneously with the samples, in order to have the same basis for comparison. The hope was that the standard curve growth OD values would correspond with known concentrations, and so sample concentrations could be interpolated based upon the standard. folKE, which was cloned into a constitutive high-copy plasmid, was tested with and without the addition of 500 ng of PABA during inoculation. folB, which is in an inducible copy plasmid, it was tested induced to high-copy as well as uninduced low-copy, with and without 500 ng of PABA during inoculation. We assayed both the supernatant and the cell lysate, though only the supernatant had measurable results. The standard curve is linear in the expected range from .1 to 1ng folate, though the actual absorbance values do not correspond to sample values. Although the reasons for this were unclear, the growth data for the samples are very encouraging since the relative folate levels match what we would expect. We see that the addition of 500 ng of PABA during inoculation dramatically increases overall folate levels for folKE relative to the samples without PABA. Furthermore, adding PABA to the wild type controls did not affect growth at all, suggesting that the assay bacteria L.rhamnosus was not metabolizing the extra PABA. The extremely high OD values for all the samples were possibly the result of not completely washing out all of the culture media prior to adding the L.rhamnosus to the assay samples. When we repeated the assay in duplicate, this time on folB as well, we were able to observe the same trends in growth with and without the addition of PABA. Again, we see that for folKE, the addition of PABA does increase total folate levels, though not as dramatically as before. The rampant growth of the wild type control is disconcerting, but wild type folate production again appears to be unaffected by the addition of PABA. Furthermore, folate levels for folKE are still higher than the control where L.rhamnosus was added to only media without supernatant. And what of folB? Recall that folB was the only gene to be successfully cloned into an inducible-copy plasmid, and so it was tested both induced and uninduced. The folate levels in the induced sample (high-copy) are higher than in the uninduced (low-copy) sample, which is consistent with what we would expect. The addition of PABA to both induced and uninduced increases relative levels of folate, which is also consistent. However, it is interesting to note that folate levels for the +PABA samples are the same for induced and uninduced. Of course, given the small sample size, this could just be due to variability, but it could also suggest that folate production reached an upper limit. This explanation seems even more likely if we reconsider the folate biosynthesis pathway, and we see that folB and folKE are both located upstream of actual integration of PABA into the molecule, accomplished by folP. It is very possible that we are increasing the flux of both pathways going into the folP junction, but as we were unable to overexpress folP as well, we may have created a bottleneck.

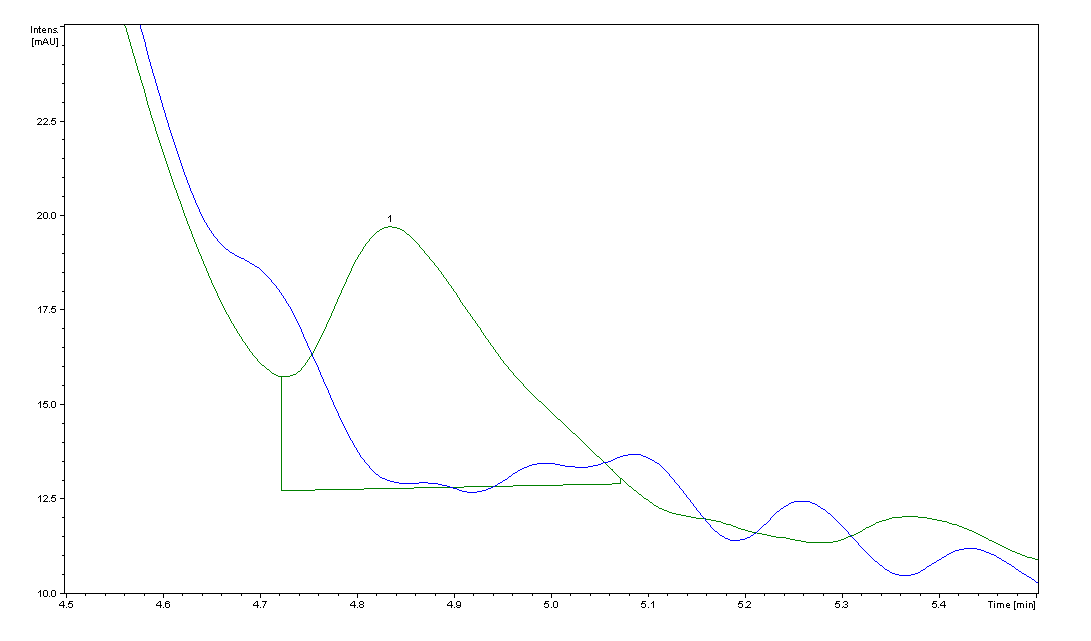

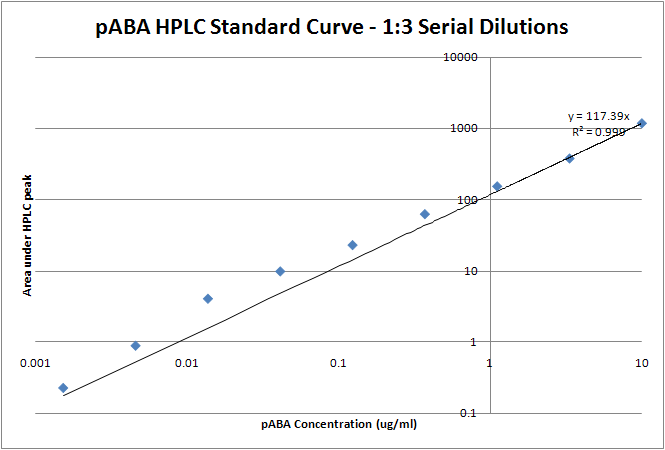

para-Aminobenzoic Acid (pABA) HPLC Assay Results for pabAUsing high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) we were able to detect PABA peaks from overexpression of pabA compared to a control sample of wild type supernatant. Compared to the peak areas of the standard curve, we were able to use a linear approximation to determine the concentration of PABA to be 703.2 ng/mL for pabA overexpression. Conclusions and Future WorkWe have shown, through very preliminary tests, the feasibility of overproduction of folate in E. coli using genes originally derived from L. lactis. Our data have confirmed previous studies in the necessity of overexpressing both folate and PABA synthesis genes, and we have shown that folate appears to be mostly present in the supernatant. Our data also suggest that overexpression of folKE is the most effective, definitely more effective than folB, and possibly more effective than overexpressing folB + folKE. We have also shown that it is possible to overexpress para-aminobenzoic acid production in E. coli and that overexpression of pabA increases total levels of para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA). Further work on this project would include repeating the folate assay to generate more data, perfecting the assay in order to quantify folate levels with the standard curve, making the pabA + pabB and folB + folKE constructs, making a folB + folKE + pabA + pabB construct, and extracting and cloning folP from the L. lactis genome. Relevant PartsBasic Parts

Construction Intermediates

Composite Parts

References[1] Asrar FM and O’Connor DL. Bacterially synthesized folate and supplemental folic acid are absorbed across the large intestine of piglets. J Nutr Biochem 2005 Oct; 16(10) 587-93. [2] BD Biosciences. Folic Acid Assay Medium. [http://www.bd.com/ds/technicalCenter/inserts/Folic Acid Assay Medium.pdf] [3] Bermingham A and Derrick JP. The folic acid biosynthesis pathway in bacteria: evaluation of potential for antibacterial drug discovery. Bioessays 2002 Jul; 24(7) 637-48. [4] Bernstein JR, Bulter T, and Liao JC. Transfer of the high-GC cyclohexane carboxylate degradation pathway from Rhodopseudomonas palustris to Escherichia coli for production of biotin. Metab Eng 2008 May-Jul; 10(3-4) 131-40. [5] Camilo E, Zimmerman J, Mason JB, Golner B, Russell R, Selhub J, and Rosenberg IH. Folate synthesized by bacteria in the human upper small intestine is assimilated by the host. Gastroenterology 1996 Apr; 110(4) 991-8. [6] Corcoran BM, Stanton C, Fitzgerald GF, and Ross RP. Growth of probiotic lactobacilli in the presence of oleic acid enhances subsequent survival in gastric juice. Microbiology (2007), 153, 291299. [7] Image of L. rhamnosus <http://www.yaklasansaat.com/resimler/2008haberresimleri/haber subat resim/subat19 lactobacillus rhamnosus.jpg> [8] Gabelli SB, Bianchet MA, Xu W, Dunn CA, Niu ZD, Amzel LM, and Bessman MJ. Structure and function of the E. coli dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatase: a Nudix enzyme involved in folate biosynthesis. Structure 2007 Aug; 15(8) 1014-22. [9] Horne DW and Patterson D. Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay of folic acid derivatives in 96-well microtiter plates. Clin Chem 1988 Nov; 34(11) 2357-9. [10] Morita M, Asami K, Tanji Y, and Unno H. Programmed Escherichia coli cell lysis by expression of cloned T4 phage lysis genes. Biotechnol Prog 2001 May-Jun; 17(3) 573-6. [11] Sheng H, Knecht HJ, Kudva IT, and Hovde CJ. Application of bacteriophages to control intestinal Escherichia coli O157:H7 levels in ruminants. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006 Aug; 72(8)5359-66. [12] ArdeyPharm. Mutaphor, the probiotic drug for life![http://www.ardeypharm.de/pdfs/en/mutaflor drugforlife e.pdf] [13] Sybesma W, Burgess C, Starrenburg M, van Sinderen D, and Hugenholtz J. Multivitamin production in Lactococcus lactis using metabolic engineering. Metab Eng 2004 Apr; 6(2) 109-15. [14] Sybesma W, Starrenburg M, Kleerebezem M, Mierau I, de Vos WM, and Hugenholtz J. Increased production of folate by metabolic engineering of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003 Jun; 69(6) 3069-76. [15] Wegkamp A, Starrenburg M, de Vos WM, Hugenholtz J, and Sybesma W. Transformation of folate-consuming Lactobacillus gasseri into a folate producer. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004 May;70(5) 3146-8. [16] Wegkamp A, van Oorschot W, de Vos WM, and Smid EJ. Characterization of the role of para-aminobenzoic acid biosynthesis in folate production by Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007 Apr; 73(8) 2673-81. [17] Yun J, Park J, Park N, Kang S, and Ryu S. Development of a novel vector system for programmed cell lysis in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2007 Jul; 17(7) 1162-8. [18] Zhang GF, Mortier KA, Storozhenko S, Steene JVD, Straeten DVD, Lambert WE. Free and total para-aminobenzoic acid analysis in plants with high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry: Volume 19, Issue 8 , Pages 963 - 969, 2005. [19] Zhu T, Pan Z, Domagalski N, Koepsel R, Ataai MM, and Domach MM. Engineering of Bacillus subtilis for enhanced total synthesis of folic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005 Nov; 71(11)7122-9. |

"

"