Team:Heidelberg/Project/Killing II

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Colicins - Project Description

Introduction

Pathogenous bacteria or even cancer cells are often hard do kill or even to sense. Therefore the iGEM team Heidelberg decided this year to work on a production of a bacterial machine that will be able to sense, swim towards and kill pathogens or even cancer cells.

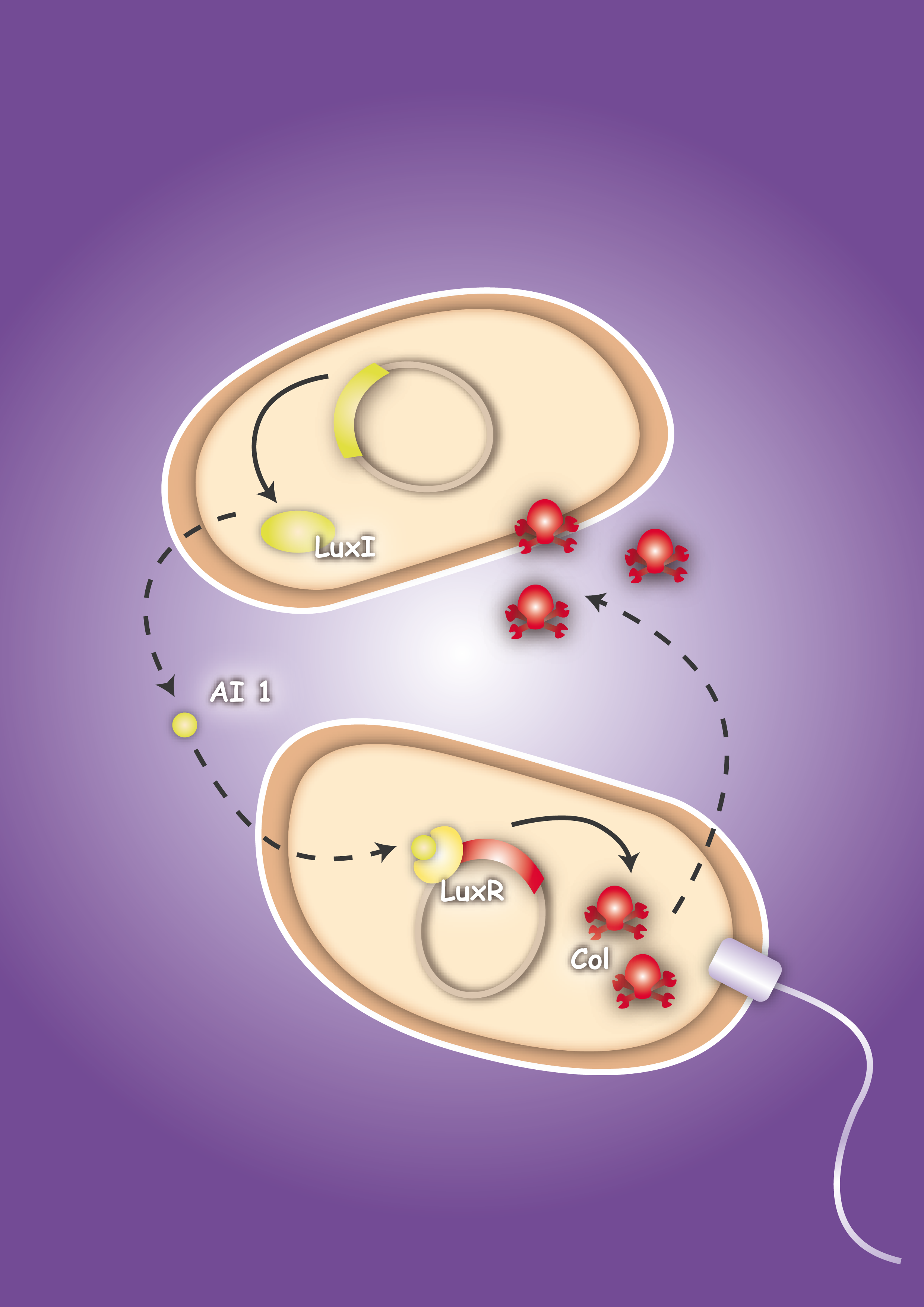

To proof in principle the feasibility of this system two E. coli strains were created, one prey strain and one killer strain. The prey strain emblematizing the pathogen produces certain, for this pathogen typical, molecules. For testing the system molecules of the quorum sensing system of Vibrio fischeri, Autoinducer-1 (AI-1 or AHL) and Autoinducer-2 (AI-2), were used. The killer strain is able to sense the secreted molecules and act as follows: by sensing the Autoinducer-2 the killer strain swims toward the pathogen. The AI-1 is responsible for the activation of the killing mechanism of the prey strain by inducing the production of a bacterial toxin, termed colicin.

Colicins are toxins produced by Escherichia coli bacteria, acting against related strains or spices. The toxin is encoded on plasmids, termed pCol, and contains in general three genes which are related to their function. The colicin gene encodes for the toxin itself. Colicins have different mode of actions. Most colicins are either pore-forming colicins (e.g. colicin E1) or have enzymatic activity, as nucleases (e.g. colicin E9). Their toxicity can be inhibited by a protein-protein interaction with the immunity protein, produced by the immunity gene in order to protect the host cell against cell death. The lysis protein, produced by the lysis gene is finally responsible for the release of colicins.

For the experimental approach the nuclease colicin E9 and the pore-forming colicin E1 were used. The functionality was only shown for colicin E1 which is also known to inhibit the growth of bacteria and eukaryotic cell lines.

Theoretical Background

The main idea of the project was to create a system to kill pathogens or even harmful eukaryotic cells such as tumour cells. Therefore, secreted molecules of these pathogens are sensed by a generated bacterial killing strain and will be killed with the help of a secreted toxin. Bacteriocins are toxins, more precisely ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides [1], produced by certain bacteria. These toxins are active against other bacteria of the same species or against bacteria of other species. [1] The host bacterium is immune to the toxin due to production of immunity proteins. [1] To establish the project it was decided to test the system with Escherichia coli bacteria and their bacteriocins, so called colicins. Colicins are proteins produced by certain strains of E. coli that are lethal for related E. coli strains. Colicin was first identified by Gratia in 1925 who also established the name „colicin“, coming from its producing bacteria (E. coli). [2] Most of the colicins act as nucleases or form pores in cell membranes. All colicins kill due to the presence of a receptor in the outer membrane of the target cell where the colicin binds to. [3] To enter the cell colicins use either the tol or the tonB system, which allows to classify colicins into two groups: group A and B [4], [5]. Group A colicins are translocated by the tol system such as Colicin A, E1-E9, K, L, N, S4, U and Y. For colicin E1, only TolA and TolQ are required whereas TolABQR and OmpF are essential for colicin E9. [6] Group B colicins comprise colicins that are translocated by the tonB system as Colicin B, D, H, Ia,Ib, M, 5 and 10. Another difference is that colicins of group B usually are not secreted, whereas colicins of group A are released into the media.[4], [5] Both, the Tol- and TonB- dependant colicins are encoded on colicinogenic plasmids, termed pCol. Colicins are organized in three domains: a reception-, a translocation- and a killing domain. These three domains are related to their steps of action, which will be described below. In nature colicinogenic strains are widespread and can be found for example in the guts of animals. However there are two classes of pCols. The type I pCol plasmids are small multicopy plasmids (6-10 kb, ~20 copies/cell) and are usually encoded by the Group A colicins. The type II pCol plasmids are large monocopy plasmids of approximately 40 kb which encode mainly for colicins of group B.

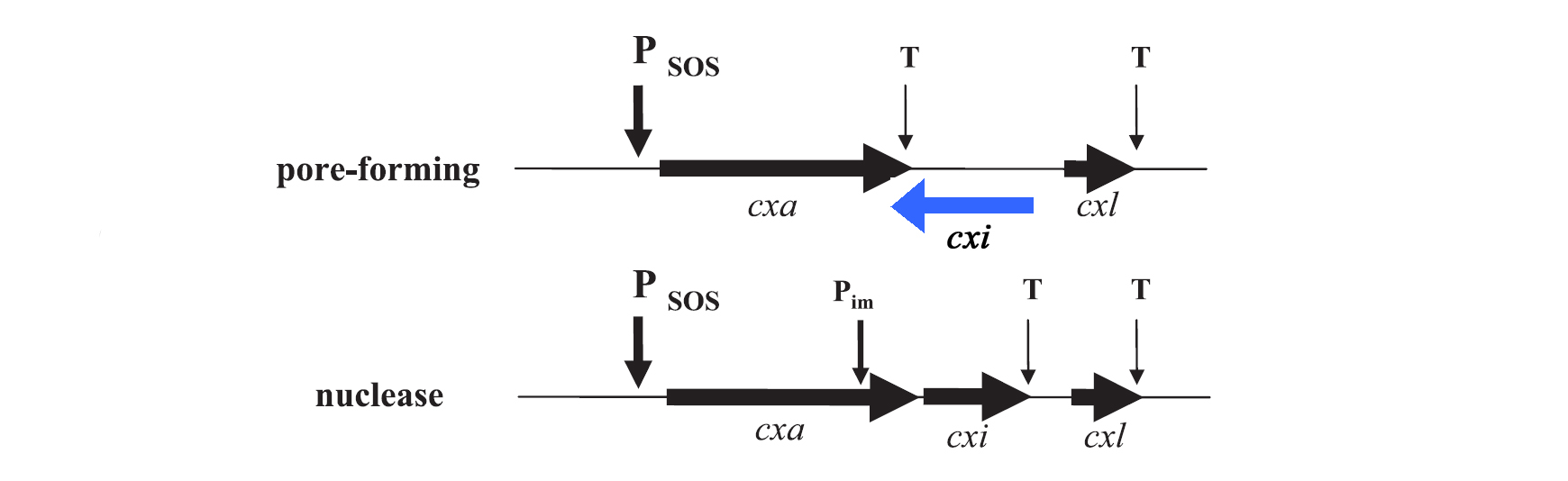

For the project the decision was to work with colicins of group A only. Their genetic organization was described by Riley et al. in 1993. [7], [8] In general plasmids of group A colicins contain three genes: a colicin gene encoding for the toxin, an immunity gene and a lysis gene (see figure 1). The colicin gene is under the control of a SOS promoter (PSOS). The promoter responds to a variety of agents such as UV-light, physical agents and stress. [9] The immunity gene is under the regulation of two promoters, the PSOS of the colicin operon and its own constitutive promoter that allows a constitutive production of the immunity protein. This ensures that there is no free colicin inside the cytoplasm, which would kill the host cell. The separated constitutive promoter is located within the structural gene of nuclease colicins. There is no immunity gene in operons encoding pore-forming (ionophoric) colicins: It is located on the opposite DNA strand of the intergenetic space between the colicin and the lysis structural gene and is transcribed from its own promoter under constitutive regulation. The last gene of the colicin operon encodes for the lysis protein, which is controlled by the same promoter as the colicin production. Due to the terminator localized downstream of the colicin gene, the lysis protein is expressed in lower amounts than the colicins. After reaching a certain threshold of lysis protein the host cell is lysed which leads to the release of colicins into the medium. [3]

Lysis proteins are small lipoproteins with a size of 27 to 35 amino acids. As the sequences of the lyses proteins from different colicins are very similar, it is supposed that they have got a common origin. The main function of the lysis protein is to trigger the release of colicin. The amount of lyses protein that is produced varies among the same environmental factors as the colicin production. The mechanism of the colicin release due to the lysis protein is not elucidated so far. Clear is that most of the colicin is released in the media, but only in a late state of release small amounts of lysis proteins were detected. This indicates an adjusted release of the colicins rather than a lysis of the whole cell.

Due to the release of the colicin into the media group A colicins are able to diffuse towards other cells. After binding to an adequate receptor on the target cell, colicin translocation starts. BtuB is the receptor for all nine colicins E and was the first that was purified. The binding domain of the colicin is located in the center of the protein. [11], [12], [13] Colicin binding to its adequate receptor is the first step of the colicin action. [12]

The essential step for the translocation is to pass the outer membrane. Therefore, a second outer membrane protein is required (mainly OmpF, but TolC for the colicin E1) which enables a correct initial binding of the colicin at the cell surface.

The toxic activity of the colicins is given due to its C-terminal domain. It either carries a pore-forming (as colicin E1) or nuclease (like colicin E9) activity. [13], [14], [15] To protect the bacteria against their own toxic product, an immunity protein is synthesized. This immunity protein binds to the C-terminal domain of the enzymatic colicins in order to prevent the death of the host cell. The immunity protein of pore-forming colicins is located in the cytoplasmic membrane. The protein-protein interaction between this immunity protein and the colicin proteins inhibits the formation of channels during the process of colicin association of the membrane. [16]

For realization of the project two different colicins were used. Colicin E9 (ColE9-J plasmid – pCK67), a colicin with nuclease activity, was received from the Kleanthous Laboratory at the University of York and the colicin E1 (pJC411), a pore forming colicin, from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ).

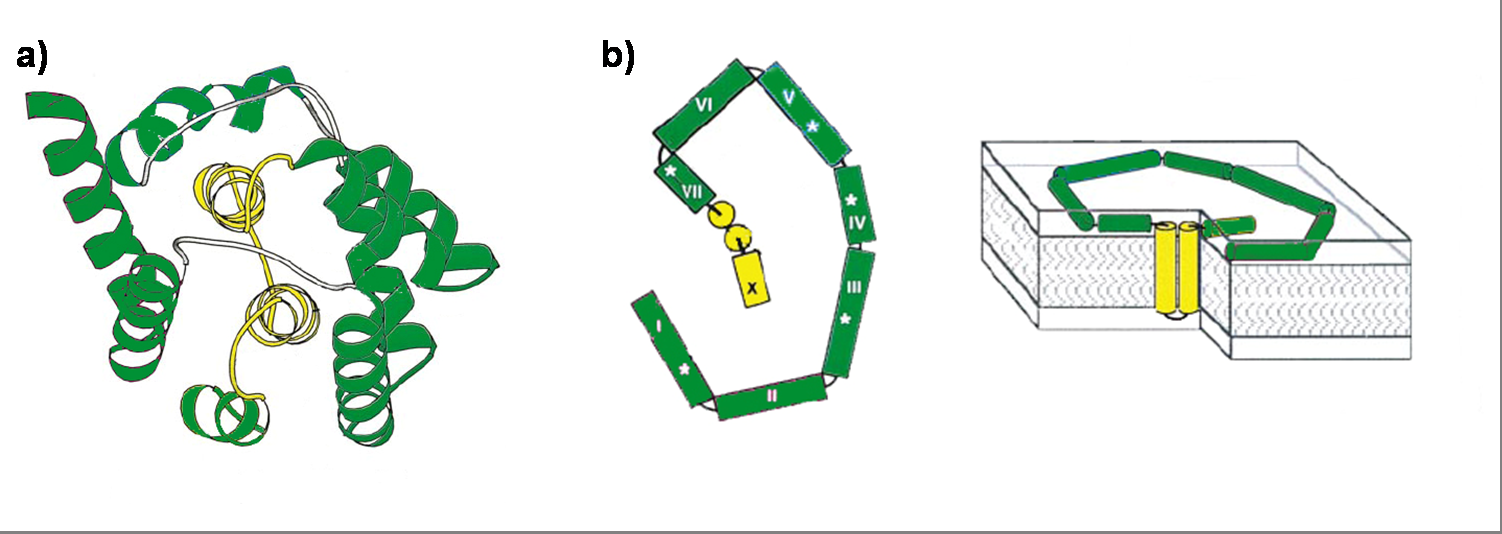

Colicin E1 is a 522 residue containing protein and belongs to the group A colicins. It kills sensitive cells, which harbour no ColE1 plasmid but contain the appropriated receptor BtuB, by forming pores, or more precisely ion channels into the inner membrane. [17] Affected cells can be E. colis or related strains but also some eukaryotic cells have been affected by the toxic activity of colicin. [18] The first step of the lethal action of colicin E1 is binding to the vitamin B12 receptor (BtuB). Colicins are able to kill bacteria by a “one hit” mechanism. This works due to destruction of the target cells cellular energy. The voltage dependant channel in the cytoplasmatic membrane leads to a depolarization of the target cell. The conductance of the channel has been shown to be ~107 ions/channel-sec in 1 M NaCl. [19] Its ability to form pores is given by the C-terminal domain. This domain consists of 10 tightly packed α–helices (see Figure 1). [20], [5] The colicin protein is a water soluble molecule containing mostly amphipathic helices except from two hydrophobic ones. Due to these two hydrophobic helices the protein is able to target the cell membrane and act as a membrane protein.

To proof that the system is functional, one prey strain, representing the pathogen, and one killer strain were generated. The quorum sensing system, which was already described in several papers and reviews [22], [23], [24], was used as cell-cell communication system. The molecules, secreted by the pathogens, were represented by acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL), originally produced by the LuxI from Vibrio fischeri. [22] The prey cell therefore contains a plasmid encoding the LuxI protein which produces AHL molecules. These molecules are able to diffuse through the cell wall and medium where they form a gradient. The killer strain, which is attracted by another molecule, swims toward the prey cell and senses the AHL molecules. The killer bacteria produce the LuxR protein. AHL molecules bind to LuxR [25] and act as transcriptional factor for the regulation of the colicin promoter PluxR. This promoter regulates the colicin production. Another interesting aspect of colicins is their ability to harm and kill tumor cells. [26]

Part Design

Results

Sender

The sender, also termed prey, is composed of a plasmid containing the luxI gene downstream of a constitutive promoter (BBa_J23107) in Escherichia coli TOP10 cells. The prey cell is responsible for continuous production of AHL through the LuxI protein expressed by the luxI gene. To generate this device, the sender part (BBa_F1610) was obtained directly from the plasmid by digestion. The vector (BBa_J61002) which already contains the constitutive promoter, was also digested. Both parts were ligated by the BioBrickTM standard assembly. To verify the right gene product, palsmid DNA of a positive clone was digested and sequenced (see Figure 6).

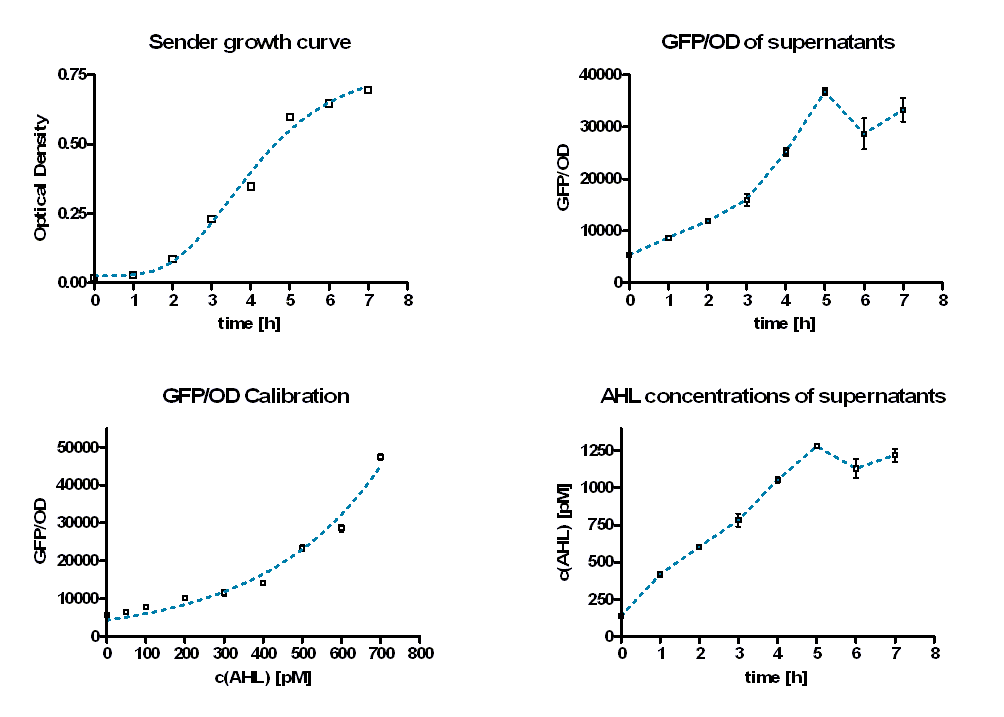

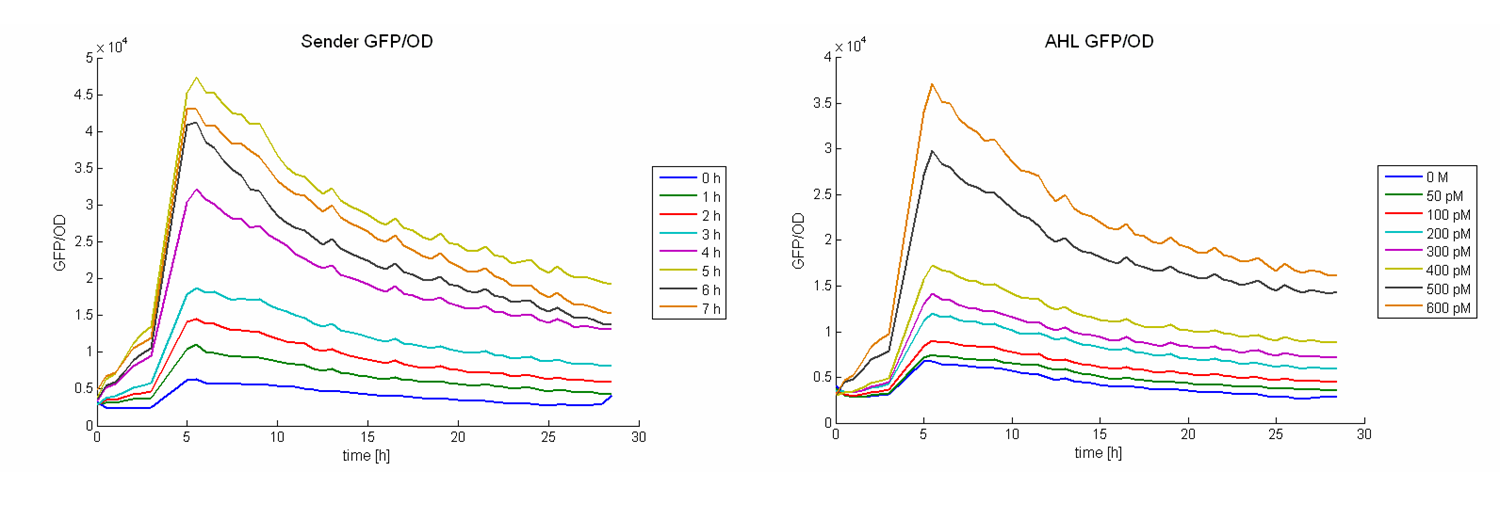

To quantify the rate of AHL production, sender activity tests were performed. Therefore sterile supernatants of liquid E. coli TOP 10 overnight cultures containing the sender part (BBa_K150000) were produced hourly. In addition, the optical density at these time points was measured to estimate the amount of producing cells (see Figure 7, top left). Afterwards the AHL concentrations of the supernatants were determined by the GFP production of E. coli containing a LuxR-GFP producing part (BBa_T9002). Therefore the supernatants were diluted with TB media and inoculated with a constant amount of the GFP producing culture.

As calibration the same measurements were performed with defined AHL concentrations. Figure 8 shows the change in GFP/OD ratio over time depending on the sender supernatants (left panel) and the preassigned AHL concentrations (right panel). The values increase during the first six hours and reach a maximum. Thereafter they decrease slightly.

The GFP/OD values at t = 10 hours were used to calculate the AHL concentrations of the supernatants. For calibration, the GFP/OD values at t = 10 h were plotted against the preassigned AHL concentrations (Figure 7, bottom left). An exponential growth curve was fitted to this data (blue dotted line; y = 4325 * e0.00346*x). The AHL concentrations of the sender supernatants were determined using the GFP/OD values at t = 10 h and the exponential regression. In the course of the time the AHL concentration increases until it reaches a certain maximum before a slight decrease (see Figure 7, bottom right, Table 1). This maximum is reached at the end of the logarithmic phase. Several replications of this test have shown that it occurs between 1100 and 1300 pM.

| time [h] | GFP/OD | GFP/OD STD | c(AHL) [pM] | c(AHL) STD [pM] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5427,847 | 48,01405 | 135,7623515 | 5,310956899 | |

| 1 | 8713,655 | 235,8338 | 418,6964705 | 16,40039009 | |

| 2 | 11849,3 | 296,7075 | 602,4247781 | 15,1577546 | |

| 3 | 15982,94 | 1123,325 | 781,2969295 | 43,55933826 | |

| 4 | 25196,72 | 720,799 | 1053,378175 | 17,34848139 | |

| 5 | 36745,75 | 652,7182 | 1278,906415 | 10,71294138 | |

| 6 | 28636,28 | 2980,17 | 1129,8639 | 65,68601047 | |

| 7 | 33271,21 | 2281,635 | 1219,533962 | 42,46359884 |

Colicin-Receiver

The killing module was created using a LuxR Receiver module (part of BBa_T9002) and different colicin operons: colicin E1 operon, colicin E9 short operon and colicin E9 long operon. All three parts were successfully assembled as described in the cloning strategy and fit the BioBrickTM standard. The following two paragraphs describe the results of the colicin E1 and E9 receivers separately.

Colicin E9

Colicin E9 is an enzymatic toxin with nuclease activity. Before the cloning of the colicin-receiver the natural toxicity of colicin E9 was tested. Therefore supernatant of lysed E. coli MG1655 cells harbouring the pColE9-J plasmid was diluted with media. The growth ability of E. coli TOP 10 cells containing BBa_I20260 was measured in this dilution. As result an efficient killing of these bacteria was observed (see Figure 1). A reference experiment with supernatant of MG1655 cells showed normal growth behaviour.

After verifying the activity of the colicin E9 protein the plasmid was extracted. Two different length of parts were amplified by PCR (see figure XX) and extracted from the gel.

In parallel the receiver part (BBa_T9002) was amplified by PCR. The product, containing a Ptet promoter, the luxR gene followed by the PluxR promoter and a ribosome binding site was also extracted from the gel (see figure XX). The pSB1A2 plasmid containing the receiver insert (BBa_T9002) was used to construct the vector (see figure XX).

The vector and the amplified receiver part were digested and ligated. Using colony PCR screening positive clones were selected. Plasmids of these colonies were digested and send for sequencing to confirm the results. To receive a functional colicin producing cell the short and long fragment of colicin E9 and the produced pSB1A2-receiver were digested and ligated. The final product, containing the receiver part and the colicin E9 genes was confirmed by sequencing.

After the successful combination of the LuxR-receiver with the colicin E9 operons the short colicin E9 receiver was finished. For the long fragment an EcoRI site was mutated (silent mutation) to fit BioBrickTM standard. To test the production and release of the toxin, several tests were performed but showed no proper activity so far. Further test will be necessary to study the killing ability of both colicin E9 receivers.

Colicin E1

Colicin E1 is, in contrast to the enzymatic colicin E9, a pore-forming toxin. Its natural toxicity was tested as described for colicin E9. The prey cells were not able to grow in colicin E1 supernatants which prove their toxicity (see Figure 9).

After the activity tests of the colicin E1 protein the plasmid was extracted and the colicin E1 operon amplified by PCR (see Figure 11). The gel extraction of the colicin E1 was digested and stored for the second cloning step. In addition a part of the receiver (BBa_T9002), allocated by the registry, was partly amplified by PCR. The product, containing a Ptet promoter, the luxR gene followed by the PluxR promoter and a ribosome binding site was also extracted from the gel (see Figure 11). The pSB1A2 plasmid containing the receiver insert (BBa_T9002) was used to gain the vector (see Figure 11).

The vector and the amplified receiver part were digested and ligated. Via colony PCR screening positive clones were selected. The plasmids of these clones were digested and send for sequencing to confirm the results. To receive a functional colicin producing cell the colicin E1 operon and the produced pSB1A2-receiver were digested and ligated. The final product, containing the receiver part and the colicin E1 genes, was confirmed by sequencing and digestion (see Figure 12).

To fit BioBrickTM standard, four restriction sites (one EcoRI, three PstI) of the colicin E1 – LuxPRwere mutated via mutagenesis PCR.

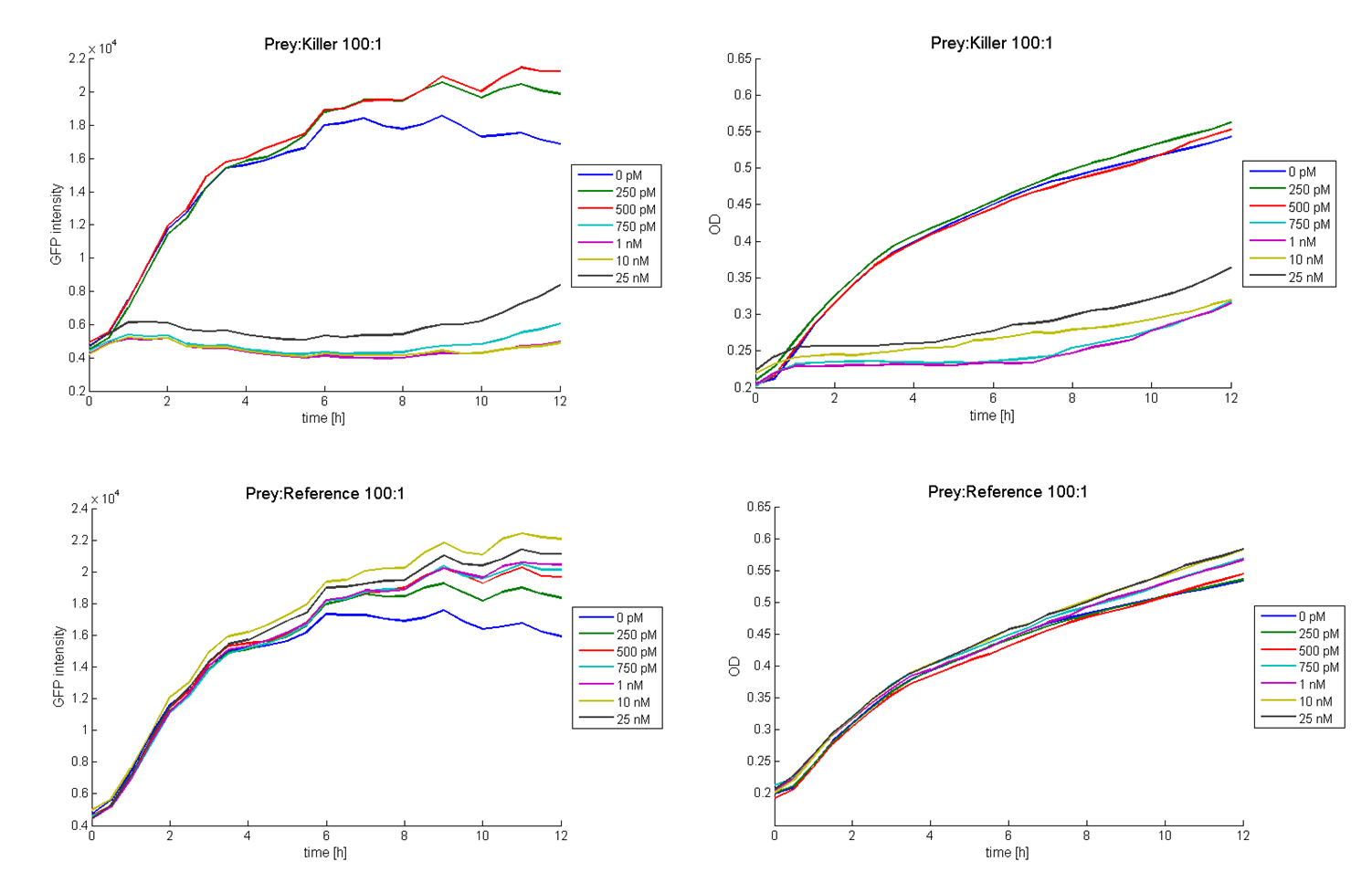

The functionality of this receiver was first tested with supernatant assays. After the confirmation of its functionality, further studies were performed. Therefore cells (E. coli TOP 10 containing the BBa_I20260; plasmid for GFP-labelling) working as prey cells were directly added to killer cells which were induced using AHL. Several experiments with different “prey”-killer ratios as well as certain AHL concentrations were performed to describe the characteristics and limitations of the killing part. Figure 13 shows results of tests with a prey-killer ratio of 100:1. It is visible that the GFP intensity correlates with the optical density. For this reason the GFP intensity was used as marker for the living prey cells in the following experiments.

In experiments where killer cells were used and the amount of AHL in the medium was sufficient, all prey cells were killed. In reference experiments (see Figure 13, bottom) using E. coli TOP 10 cells harbouring a LuxR receiver without colicin operon (comparable to part BBa_T9002 without GFP), the prey cells were able to grow for all AHL concentrations. These results suggest the lethal action of the killing part.

In addition we observed that the killing efficiency is related to the AHL concentration in the medium. Figure 14 shows a dose-response curve of GFP intensity after 12 hours dependent on different AHL concentrations. The PLuxR promoter has to be activated with an AHL concentration above 500 pM. Thus enough colicin E1 is produced and released to kill the prey cells (Figure 14).

Regarding the prey survival, dependent on the prey killer ratio, several effects can be observed (see Figure 15). Having a prey-killer ratio of 1:1, or even a higher killer fraction, all prey cells were already killed when no AHL is present. This effect is caused by the leakiness of the PLuxR promoter. For prey-killer ratios between 5:1 and 100:1 the killing efficiency can be regulated by the AHL concentration. In experiments having prey-killer ratios higher than 100:1 the growth of the prey strain was not influenced.

Besides the killing efficiency the lysis of the killer strain was analyzed. Therefore growth curves of killer cells (E. coli TOP10) induced with different AHL concentrations were measured (see Figure 16). No effect can be observed during the first hour. Afterwards cell lysis dependent on AHL concentrations can be observed. For AHL concentrations between 0 M and 1 nM only few cells were lysed. Thus growth of the population is hardly influenced. Concentrations from 5 nM up to 25 nM show a strong effect. For 5 nM and 10 nM the growth curves flattens out. After reaching a maximum during the third and fourth hour the population size decreases and converges to a constant value. For higher AHL concentrations, e.g. 25 nM, the same effect can be observed, but it is much stronger. The population only shows a weak growing tendency but then converges directly to a constant size. In addition to these growth measurements lysis of the killer cells was observed under the microscope. Figure 17 shows a killer cell which is induced by AHL (left panel, t = 0 min). After 30 minutes the cell is lysed (right panel).

Further tests on other bacteria strains as well as comparisons to effects caused by purified colicins are planed to elucidate possible applications.

Final Prey-Killer System

To proof the functionality of the system a prey strain containing a GFP producing part (BBa_I20260) as well as the luxI sender part (BBa_K150000) and a killer strain containing the LuxR-colicinE1-receiver (BBa_K150009) were designed (both E. coli TOP 10). Therefore the prey cells were able to produce and release AHL which activates the PluxR promoter and subsequently colicin production in killer cells. The system was tested for different prey-killer ratios with GFP measurements over 12 hours. Figure 18 shows that the prey cells were killed for prey-killer ratios from 1:1 up to 25:1. Therefore it is proven that our system works as expected.

Eukaryotic killing Assay (Preliminary Results)

The toxicity of colicin E1 on eukaryotic cells was tested by using breast cancer cells (MCF-7) and inoculating them in vitro with killer and reference cells for several hours.

Mcf-7 cell death was evaluated by % of cells stained with PI over time, having cells without E. coli or with non-producing Colicin strains as control (Figure 1). E. coli-mCherry was also quantified (data not shown). The PI measurements (filter FL3-620nm) were gated only to Mcf-7 cell population (see Histogram 1).

The initial results show that killing by E. coli producing colicin E1 is effective on eukaryotic cancer cells (MCF-7). Propidium iodide (or PI) is an intercalating agent and a fluorescent molecule with a molecular mass of 668.4 Da that can be used to stain DNA. It can be used to differentiate, apoptotic and normal cells, since is a membrane impermeant and generally excluded from viable cells. The high percentage of positive PI cells refers to cells that are permeable to it, thus, going into apoptosis. In this assay, after only 2h of incubation with the eukaryotic cells the death rate was close to 40% of the whole cell population. In comparison with the control conditions (Mcf-7 alone + PI), where the dead cells (maximum of 5%) are due to the trypsin treatment the effect is clear. Furthermore, looking at the eukaryotic cell death under incubation with the Reference strain (LuxR-receiver TOP 10), it can be suggested that the simple incubation of these mammalian cells with bacteria is causing cell death over time (maximum of 20% after 5 h). This effect is highly enhanced when the bacteria produce colicin E1 (maximum of 37% at 2 h) and much earlier. After 5h, both bacterial strains produce close results in killing the mammalian cancer cells. After reaching a peak, the killing efficiency goes down, being the peak of E. coli producing colicin E1 significantly higher then the reference strain.

Therefore, our preliminary results suggest that colicin E1 producing E. coli bacteria might be able to kill cancer cells at a high rate. However, more studies are needed to provide the correct insight on these events, as it might be by other pro-apoptotic markers, by repeating this experiment with more detailed conditions (timepoints, autoinducer concentrations, another eukaryotic cell type). Future studies should yield enough information about the colicin target in eukaryotic cells and perhaps an answer about how it can kill cancer cells and spare healthy ones.

References

[1] Cotter P. et al.(2005) Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3: 777–788

[2] Gratia A. (1925) Sur un remarquable example d'antagonisme entre deux souches de colibacille. Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol. 93: 1040–2.

[3] Cascales et al. (2007) Colicin Biology. Microbio. and Mol. Bio. Rev. 71(1): 158-229

[4] Davies J. et al. (1975) Genetics of resistance to colicins in Escherichia coli K12: cross-resistance among resistance of group B. J. Bacteriol. 123:96–101

[5] Davies, J. et al. (1975) Genetics of resistance to colicins in Escherichia coli K12: cross-resistance among resistance of group A. J. Bacteriol. 123:102–117

[6] Lazzaroni, J. (2002) The Tol proteins of Escherichia coli and their involvement in the translocation of group A colicins. Biochimie. 84: 391–397.

[7] Riley M. (1993). Molecular mechanisms of colicin evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10: 1380–1395.

[8] Riley M. (1993). Positive selection for colicin diversity in bacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10: 1048–1059.

[9] Lwoff A. (1952) Induction of bacteriophage production and of a colicin by peroxydes, ethyleneimines and halogenated alkylamines. C. R. Acad. Sci. 234: 2308–2310

[10] Sabet S. et al. (1973) Purification and properties of the colicin E3 receptor of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 248: 1797–1806

[11] Brunden, K. (1984). Purification of a small receptor-binding peptide from the central region of the colicin E1 molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 259: 190–196.

[12] Ohno-Iwashita Y. (1980). Assignment of the functional loci in colicin E2 and E3 molecules by characterization of their proteolytic fragments. Biochemistry 19:652–659.

[13] Ohno-Iwashita Y. (1982). Assignment of the Functional Loci in the Colicin El Molecule by Characterization of Its Proteolytic Fragments J. Biol. Chem. 257: 6446-6451

[14] Bullock J. (1983) Comparison of the macroscopic and single channel conductance properties of colicin E1 and its COOH-terminal tryptic peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 9908–9912.

[15] Pommer A. (1998) Enzymological characterization of the nuclease domain from the bacterial toxin colicin E9 from Escherichia coli Biochem. J. 334: 387-392

[16] Lindeberg M. (2001) Identification of Specific Residues in Colicin E1 Involved in Immunity Protein Recognition. J Bacteriol. 183: 2132–2136

[17] Cramer W. et al. (1990) Structure and dynamics of the colicin E1 channel. Molecular Microbiology 4: 519-526.

[18] Smarda J. et al. (2001) Cytotoxic effects of colicins E1 and E3 on v-myb-transformed chicken monoblasts. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 47: 11–13.

[19] Bullock J. et al. (1983) Comparison of the macroscopic and single channel conductance properties of colicin E1 and its COOH-terminal tryptic peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 9908–9912.

[20] Elkins P. et al. (1997) A mechanism for toxin insertion into membranes is suggested by the crystal structure of the channel-forming domains of Colicin E1. Structure. 5: 443-458.

[21] Lindeberg M. et al. (2000) Unfolding Pathway of the Colicin E1 Channel Protein on a Membrane Surface. J. Mol. Biol. 295: 679-692

[22] Waters C. et al. (2005) Quorum sensing: Cell-to-Cell Communication in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21: 319–46

[23] Joost C et al. (2008) Small Molecules for Interference with Cell-Cell-Communication Systems in Gram-Negative Bacteria, 13: 2144-2156

[24] Lazdunski A. et al. (2004) Regulatory Circuits And Comminication in Gram Negative Bacteria. Natur reviews Microbiology. 2:| 581-592

[25] Engebrecht J. et al. (1984) Identification of genes and gene products necessary for bacterial bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81: 4154–58

[26] Smarda J. et al. (2001) Cytotoxic effects of colicins E1 and E3 on v-myb-transformed chicken monoblasts. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 47: 11–13

[back]

"

"