Team:University of Ottawa/Modeling

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Modeling

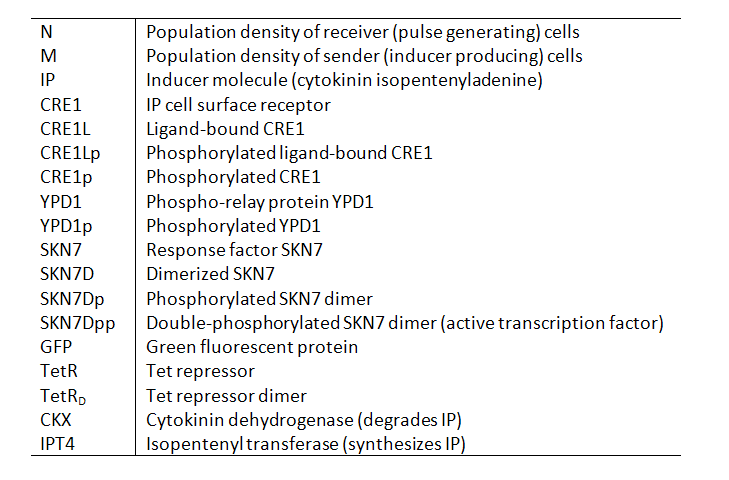

Variables

Our models contain the following variables and species:

Parameters

The values for the parameters governing expression of the core signaling components (IP, CRE1, YPD1, SKN7) were taken from the model of Chen and Weiss [ 1 ]. The parameters specific to our system were either gleaned from other sources if available, or were varied within reasonable ranges to explore their effect on the dynamics of the system.

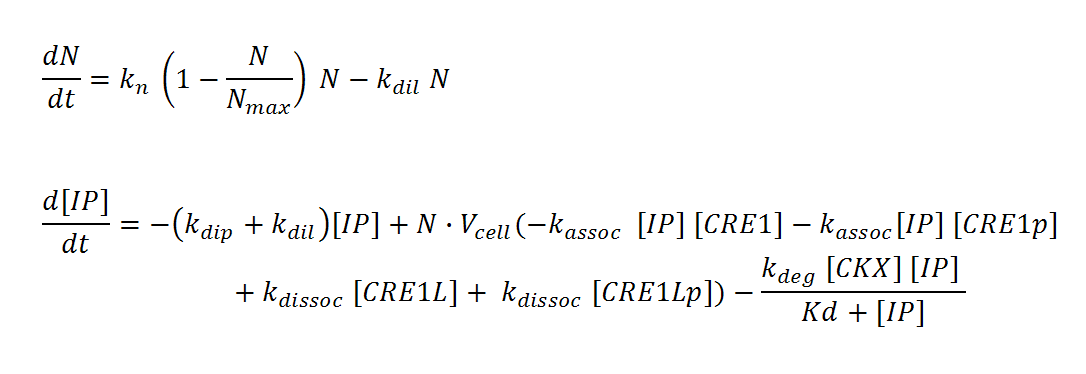

Receiver cells

N, M and IP are total culture variables. Cell density (N, M) is modeled as logistic growth, with carrying capacity Nmax, Mmax. Continuous culture dilution may be chosen rather than batch culture by setting a nonzero dilution rate (kdil). Inducer concentration (IP) in the reactor is affected by an overall degradation rate (kdip), the culture dilution rate (kdil), and binding/releasing of the molecule to the receptor in both its phosphorylated (CRE1p) and non-phosphorylated (CRE1) state. IP is assumed to diffuse rapidly across the cell membrane so that intracellular and total culture IP concentrations are the same at all times. The effective “receptor concentration” in the total reactor volume (mol receptors/culture volume) is estimated by multiplying the cellular concentration of receptors (mol receptors per cell/cell volume) by the cell density times cell volume. Simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics is used to model enzyme-mediated degradation of IP by CKX. With these assumptions, we derive the differential equations below (adapted from Chen and Weis [ 1 ]).

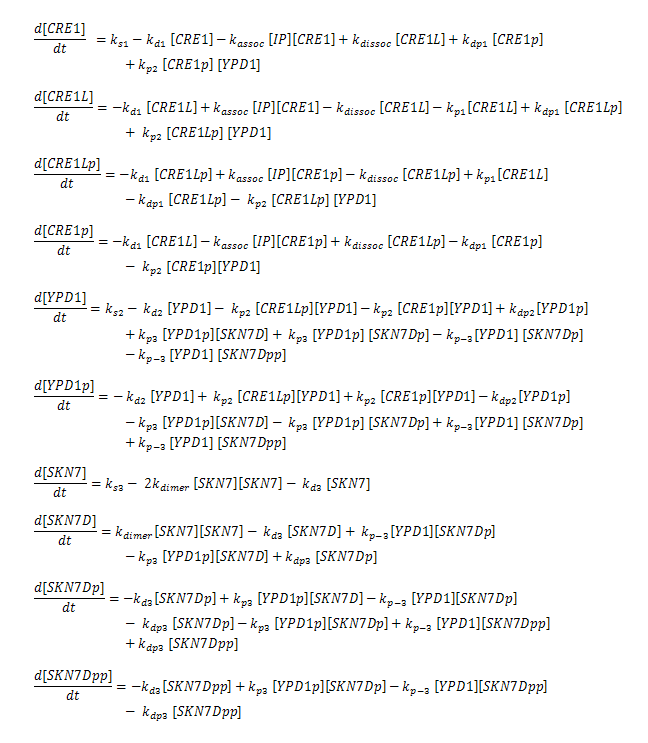

For the SKN7 signal transduction pathway, we use the model described by Chen and Weiss [ 1 ]. The corresponding differential equations are shown below. It is assumed that IP binds CRE1 with 1:1 stoichiometry. Ligand-bound CRE1 autophosphorylates and transfers its phosphate to the second messenger YPD1. The response protein SKN7 forms a dimer SKN7D. SKN7D is phosphorylated twice via reversible phosphor-transfer by YPD1. The double phosphorylated SKN7Dpp is the active transcription factor. The kinetics for the reactions are approximated using elementary mass action kinetics. These equations represent the changes in a single cell of the population. More precisely, they represent the single cell dynamics averaged over the whole population.

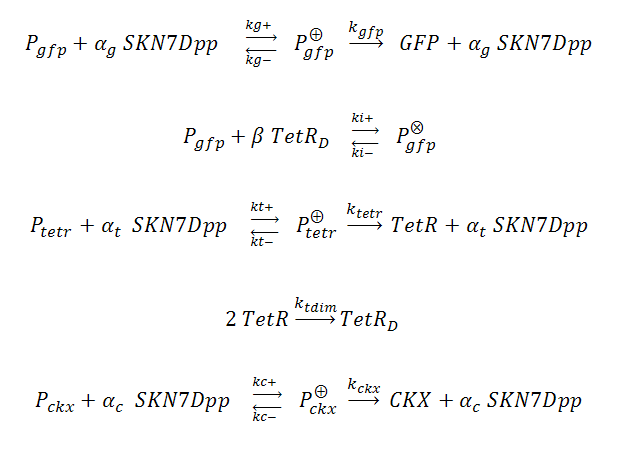

In our system, three genes are under the control of SKN7Dpp: the gene of interest (GFP) is expressed fastest, followed by expression of the TetR repressor, which dimerizes and binds to tet operator (tetO) elements upstream of the GFP cassette, inhibiting its expression and thus creating a “pulse” of GFP. Meanwhile, the product of the third SKN7-induced gene, cytokinin dehydrogenase (CKX), accumulates and degrades IP in the culture, allowing the system to reset itself for another pulse. The GFP, TetR and CKX genes are regulated by different promoters each possessing synthetic SKN7 response elements (SSRE).

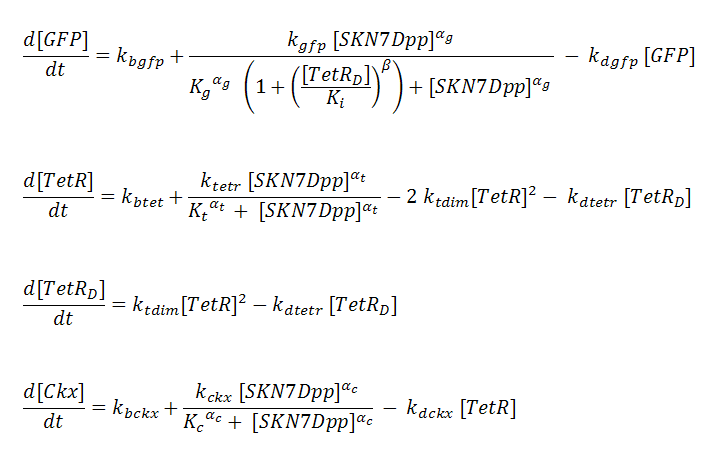

P_^+ represents the activator-bound promoter, while P_^x represents repressor-bound promoter. TetR binding is assumed to block access of SKN7Dpp to the promoter. Transcription is considered to be rate limiting for gene expression and the kinetics for transcription are modeled as Hill-type. Using the pre-equilibrium assumption for binding of the transcriptional activator SKN7Dpp and repressor TetR to their respective sites on the promoters, we derive the following equations from the reactions above:

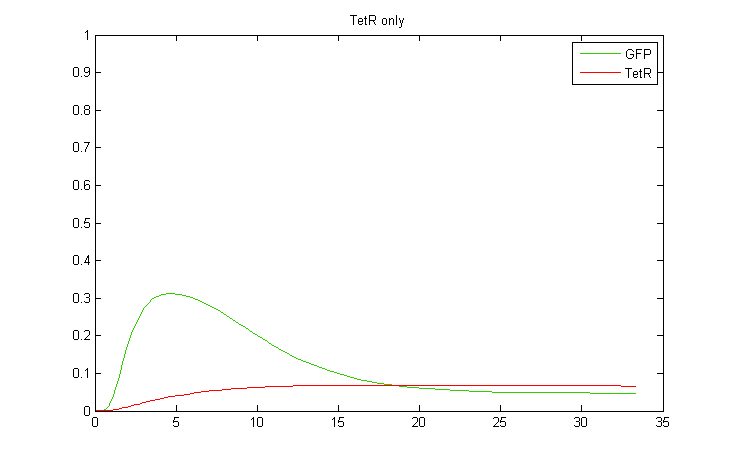

To test the behavior of our pulse generator, simulations were run using MatLab. For example, the diagram below shows the change in concentration of each of the species during a simulation of the pulse generator (receiver) strain responding to an initial spike in inducer (IP) concentration:

Here it is assumed that cells are growing in a continuous culture bioreactor (or, equivalently, a fed-batch reactor in which a fraction of the culture is periodically replaced with fresh media). The dilution rate is set to maintain the cell density at around 1 million/mL. The initial concentration of IP is set at 10uM.

Pulse Characteristics

For the functioning of the core pulse generator motif, important parameters include:

- SKN7 transcription kinetics

- kgfp, ktet, kckx

- max transcriptional output for each of the three genes

- modified by: TATA box mutations

- Kg, Kt, Kc

- The Hill constants for transcriptional activation by SKN7Dpp binding to the SSRE elements (actual dissociation constant for the interaction between SSRE and SKN7Dpp was not known, this value was varied from the uM to nM range in our simulations)

- modified by: using either the single or tandem SSRE configuration in our pSSRE promoters

- αg,, αt, αc

- The Hill coefficients for SKN7Dpp-mediated transcriptional activation

- kgfp, ktet, kckx

- TetR repression kinetics

- Ki

- Hill constant for binding of TetRD to the tet operator of the GFP cassette

- Modified by: using single or multiple tet operator elements

- β

- Hill coefficient for binding of TetRD to the tet operator of the GFP cassette

- Ki

- CKX enzyme kinetics

- Kdeg, Km

- Catalytic constant and Michaelis constant for the CKX enzyme – these values were obtained from the literature

- modified by: the addition of a suitable electron acceptor to the media (see discussion below).

- Kdeg, Km

First, we wanted to characterize the nature of the “pulses” produced under a constant input signal of IP (10 uM). The pulses are relatively long (usually 6-10hrs), but it must be noted that contrary to this particular case, in the application of recombinant protein expression one would normally have the protein tagged for secretion. Continuous export would accelerate the down phase of the GFP pulse.

The overall shape of the GFP pulse appeared to be very sensitive to the interplay between the kinetics of SKN7-mediated GFP transcription and TetR-mediated GFP repression. The faster TetR accumulates, the faster GFP expression is attenuated, and thus the shorter the pulse. However, there appears to be a trade-off in that faster TetR expression will also diminish the maximum expression level that GFP can attain, thus shorter pulses tend to have smaller amplitudes. To illustrate this effect, we show a simplified case where the binding and repression of GFP expression by the TetR dimer is subject to a threshold concentration of TetR. That is, TetR will only bind to the GFP promoter once it reaches a threshold concentration. This allows a gateway of time for GFP levels to rise to significant levels before being attenuated by TetR.

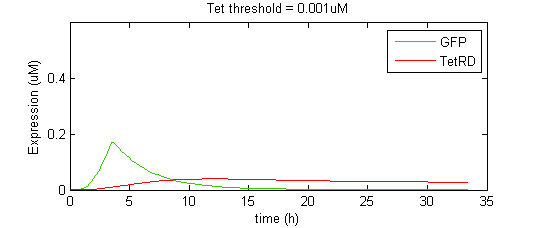

When the threshold concentration is set to 0.001uM, the result is an idealized pulse shape, biexponential-like with a sharp spike. However, if the Tet threshold is set too high, TetR is unable to completely repress GFP expression and instead GFP reaches a new, higher steady state level (although lower than it would be in the absence of TetR). Notice that the threshold level has a significant effect on the amplitude of the pulse.

In the second case, the final state is too high to really describe the effect as a pulse. Alon [ 2,3 ] describes this behavior of the Type I incoherent FFL as “response acceleration”, as opposed to pulse generation, as it represents a more rapid rise to a predetermined steady state level than would be achieved under simple autoregulation (i.e. hyperbolic rise to a max). In a more realistic scenario, the binding of a TF to a promoter in a continuous model is not perfectly step or “switch”-like, but smooth. The saturation profile for Hill-type kinetics is sigmoidal, with the Hill coefficient determining the steepness of the sigmoid (cooperativity). The higher the Hill coefficient, the more step-like is the transition.

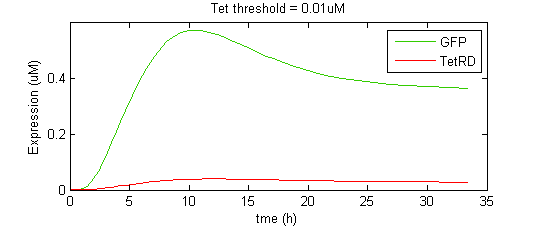

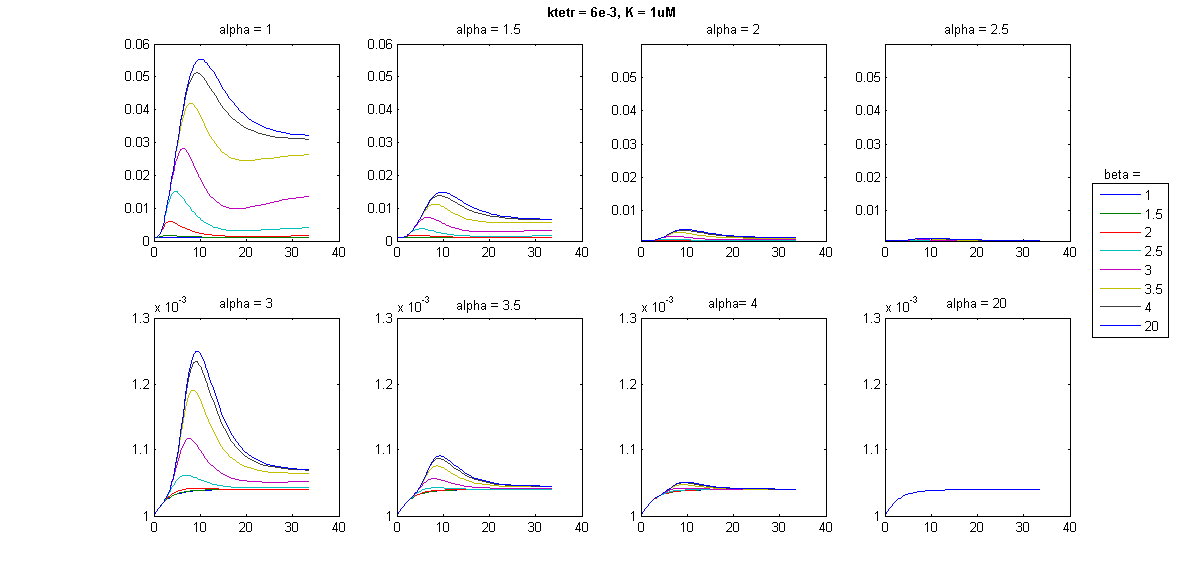

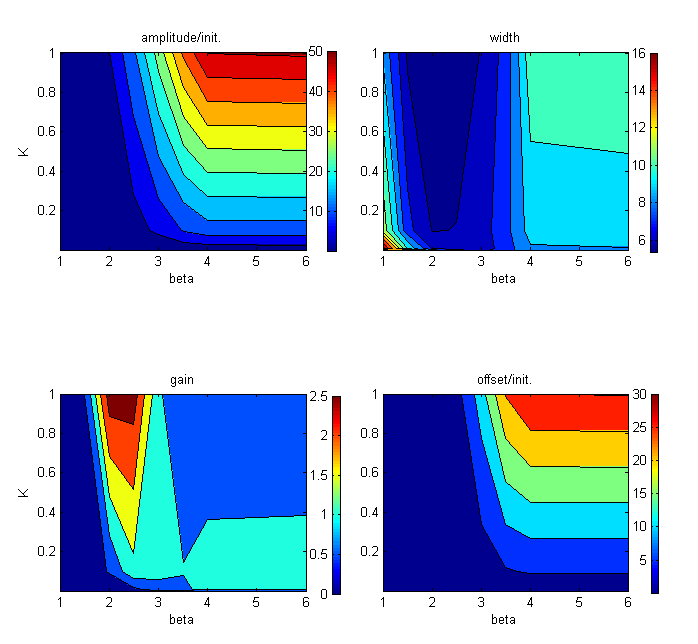

To further explore the effects on pulse characteristics, a barrage of simulations was run, using combinations of different values for the parameters governing TetR synthesis rates, and TetR and SKN7Dpp binding kinetics, including Hill parameters. Below is an example of some of the results:

It appeared that pulse characteristics were sensitive to the Hill coefficient of TetR binding (β) (just like the case of the Tet threshold) as well as the TetR expression rate (ktetr) and the Hill parameters for the expression of each of the three SSRE-regulated genes by SKN7Dpp. In some cases, nice looking pulses were produced, but the magnitude of the signal was negligible; in other cases, large pulses were produced that either were very long lasting or returned to a level much higher than the initial. In some cases, no pulse at all could be produced. The question that hence arises is: what is a “good” pulse for our purposes? To achieve a sustainable protein-expressing population, pulses should not be too low but neither should they be too high, to prevent the full-blown induction of stress responses. For the same reason, pulse duration should be short. The levels should return to one close to the initial state after the pulse, otherwise the cells may not permitted to recuperate effectively.

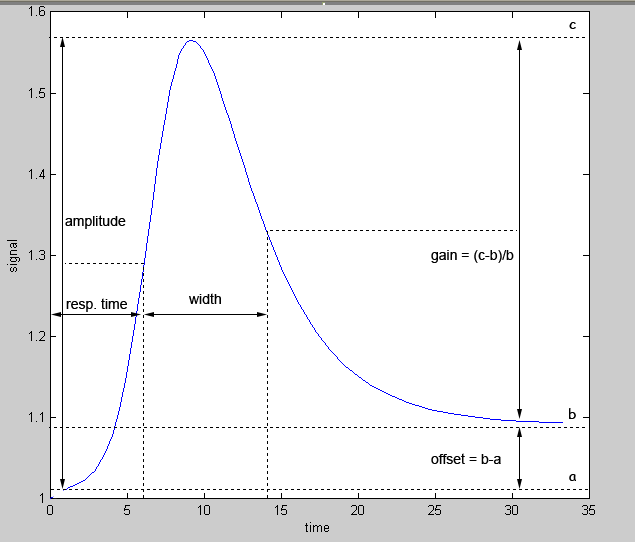

To gain a semi-quantitative notion of the effects of the different kinetic parameters on the overall pulse shape and characteristics, we define a few pulse parameters:

We define pulse amplitude as the distance between the maximum signal and the initial signal. Pulse width is the distance between the median signal of the leading edge and that of the trailing edge. Pulse gain (as defined by Basu, Weiss and colleagues [ 4 ]) is the distance between the final steady state signal and the maximum signal divided by the final steady state signal. We define the offset as the distance between the initial steady state signal before the pulse and the final steady state signal after the pulse.

These heat maps illustrate the trade-off between a high amplitude pulse and a pulse with minimal offset. As can be seen in this case (constant ktet, n = …), the GFP pulses with the highest gain and shortest width tend to have low offset, but only modest amplification from baseline expression.

Many of the parameters explored here can be modified by engineering our system. As part of our design strategy, we decided to produce an array of constructs, combining modifications in the TATA box region of the TetR and CKX promoters (ktetr, kckx) along with different numbers of tetO copies (Ki, β) in the GFP promoter and different copy numbers of SSRE elements in the promoters (Kg/αg, Kt/αt, Kc/αc). Since the effects of these modifications on transcription efficiency and binding efficiency are difficult to predict with accuracy, the best strategy to engineering a pulse with desirable characteristics is to create multiple strains containing these slightly different regulatory modifications and then screen these for the “best” pulse by experiment.

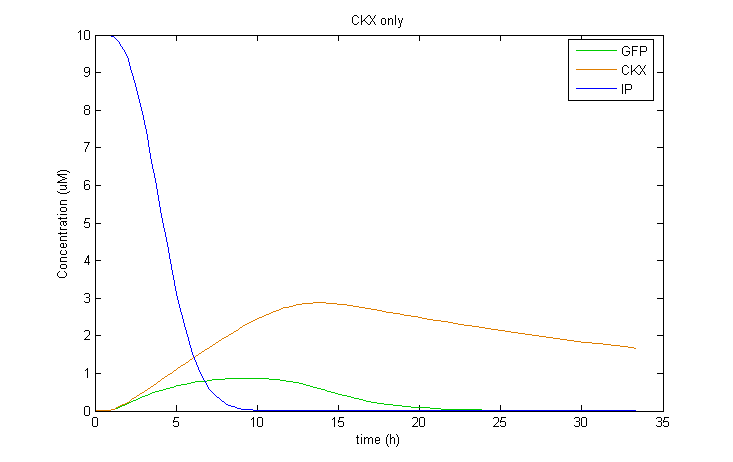

Interestingly, it was observed that when CKX expression was incorporated into the model, large extended pulses of GFP could be produced even when TetR was removed from the model! Although not ideal, this pulse generation is based on a delayed negative feedback loop of CKX onto the inducer IP, as opposed to the feedforward loop considered before. Such a configuration could in fact be sufficient to permit oscillatory dynamics in combination with a sender cell population. We therefore decided to also construct a yeast strain containing only the GFP and CKX constructs, without TetR.

Pulsilation

To continue modeling our system, a set of realistic parameters producing a “nice” pulse were chosen and incorporated into an elaborated dual population model of sender cells and receiver cells. In this case a second population of sender cells (M) constantly produce the inducer molecule IP by expressing the isopentenyl transferase IPT4 from Arabidopsis thaliana, under the regulation of the yeast GAL1 promoter, whose expression can be modulated using glucose/galactose. The receiver cells respond to IP and produce a pulse of GFP mediated by TetR; meanwhile CKX accumulates and degrades IP to yield adenine, which can be recycled by the cell’s purine metabolism pathways. The idea is that following enzymatic degradation of the inducer molecule, expression levels of all three SKN7-induced genes in the receiver cells will decline, IP will accumulate again in the media and trigger a second pulse of GFP expression in the receiver cells, and so on. In a simulation, the expectation would be to see oscillations of not only GFP, but also of TetR, CKX and IP as well.

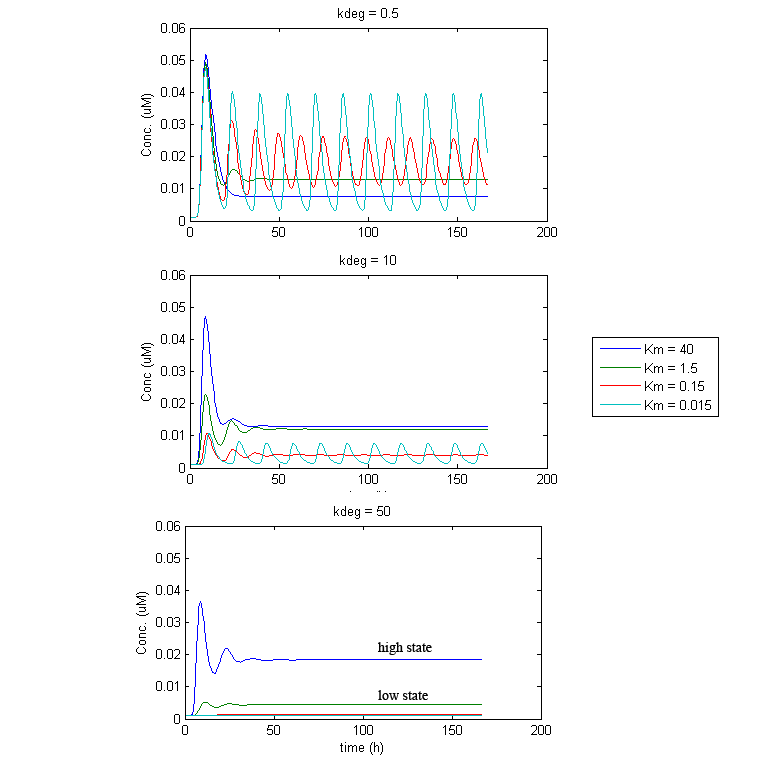

Under such a configuration, stable oscillations turned out to be difficult to obtain. Under most parameter settings, reporter levels would eventually settle to a constant steady state, sometimes undergoing damped oscillations. This appears to be the result of an eventual balance between IP-synthesis and CKX-mediated IP-degradation that quickly gets established. Thus, the dynamics are intimately related to the balance of IP and CKX levels. What is often seen is that GFP/TetR/CKX levels either settle at a “low state”, when this balance favors CKX, or they will settle at a “high state”, when the balance favours IP. However, under some conditions, stable oscillation was achievable. Although not very robust, attaining oscillations appears highly dependent on the enzymatic activity of CKX. Fortunately, it was discovered that the kinetics of CKX can be accelerated up to 4000-fold, in the presence of certain electron acceptor compounds (e.g. 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCPIP)[5] and quinones [6]). Thus it may be possible to achieve oscillations in the dual population system by adding or restricting such electron acceptor compounds in the culture media to appropriate amounts.

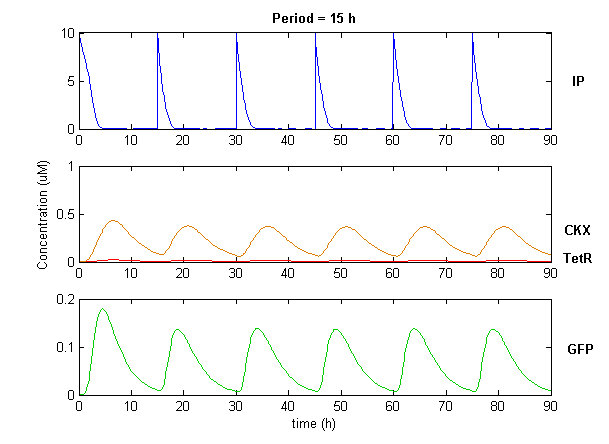

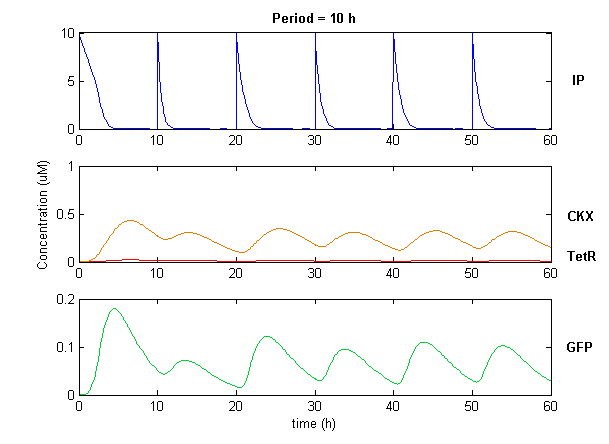

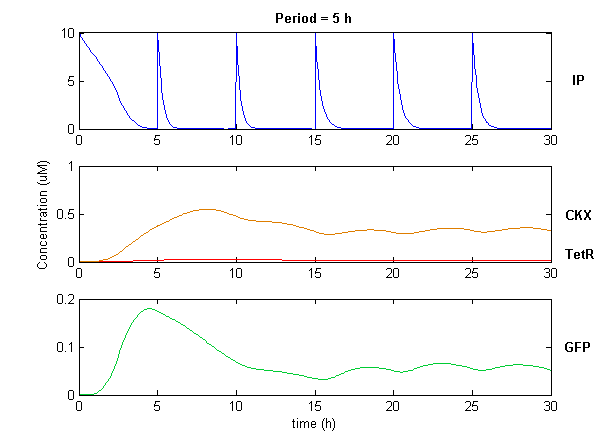

Simulation of the dual population model revealed that it is not a very robust design for the production of oscillations or pulse trains of gene expression; the main difficulty is the fact that IP is independently being synthesized at a constant rate. However, if we simulate the response of the receiver cells to periodic stimulation by IP, it becomes clear that the system can produce trains of pulses in a robust manner. Thus, our pulse generator system is amenable to periodic induction as can be achieved by manually spiking the reaction vessel periodically with IP. Another possibility would be designing a system whereby inducer synthesis in vivo is oscillatory, either in a separate population of sender cells or incorporated into the receiver cells themselves in a quorum sensing configuration. In any case, the most important factor in producing robust pulse trains (“pulsilations”) by periodic induction is to consider the refractory period of the pulses, which is determined by the half-lives of TetR and CKX, as demonstrated in the figures below. Pulse trains are observed until the period of IP addition is becomes too short for the system to reset itself.

References

[1] Weiss, R. and M.-T. Chen (2005). "Artificial cell-cell communication in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae using signaling elements from Arabidopsis thaliana." Nature Biotechnology 23(12): 1551-1555.

[2] Laskey, J.G., P. Patterson, et al. (2003). "Rate enhancement of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase using 2,6-dichloroindophenol as an electron acceptor." Plant Growth Regulation 40: 189–196.

[3] Frebortova, J., M.W. Fraaije, et al. (2004). "Catalytic reaction of cytokinin dehydrogenase: preference for quinones as electron acceptors." Biochem. J. 380: 121–130.

[4] Alon, U. (2007). "Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches." Nature Reviews Genetics 8: 450-461.

[5] Alon, U. and S. Mangan (2003). "Structure and function of the feed-foward loop network motif." PNAS 100(21): 11980-11985.

[6] Basu, S., R. Mehreja, et al. (2004). "Spatiotemporal control of gene expression with pulse-generating networks." PNAS 101(17): 6355-6360.

Blake, W., G. Balazsi, et al. (2006). "Phenotypic consequences of promoter-mediated transcriptional noise." Molecular Cell 24: 853-865.

Hillen, W. and C. Berens (1994). "Mechanisms underlying expression of Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance." Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48: 345-369.

Kleinschmidt, C., K. Tovar, et al. (1987). "Dynamics of repressor-operator recognition:Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance control." Biochemistry 27: 1094-1104.

"

"