Team:Utah State/Project

From 2008.igem.org

|

| Home | The Team | The Project | Parts | Notebook | Protocols | Links |

|---|

Contents |

Abstract

The Utah State University iGEM team project is focused on creating an efficient system for producing and monitoring PHA production in microorganisms. One goal of our research is to develop and optimize a method, using fluorescent proteins, for the detection of maximum product yield of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB, a bioplastic) in recombinant E. coli and in Cupriavidus necator. In order to develop an optimal PHB detection system, we worked to identify the most efficient reporter genes, and the best promoter sequences that would allow the GFP reporter to indicate maximum PHB production.

Project Objectives

DESIGN: PHB reporter constructs (promoter region, reporter region, and PhaCAB cassette)

BUILD: PHB reporter constructs

TEST: functionality of constructs

Introduction

Polyhydroxybutyrate

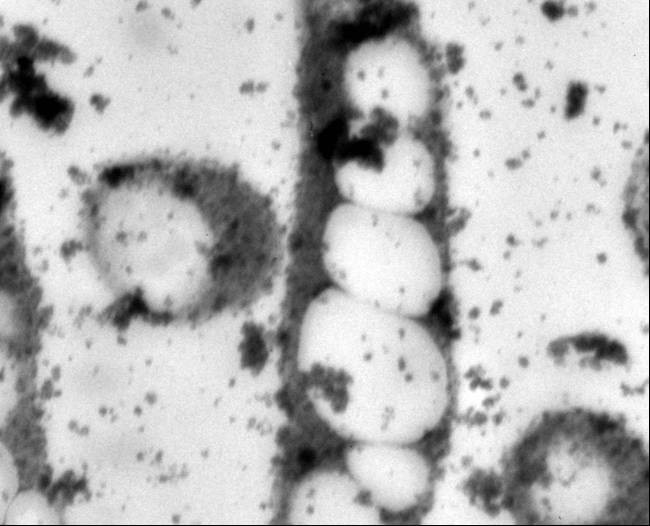

Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) is a low impact and naturally occurring biodegradable thermoplastic. It is intracellulary accumulated by a wide range of microorganisms as a carbon and energy reserve material in response to an environmental stress, such as nutrient limitation. PHB belongs to and is the most prevalent member of a broader class of polyesters called polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). Over 80 different PHAs have been classified, and each varies in mechanical properties. The difference within the polymers depends on the R side chain. Specifically, PHB possesses material properties comparable to petrochemically-derived plastics (Lee, 1999; Lee, 1996). In addition to physical and mechanical similarities with conventional plastics like polypropylene and polyethylene, its biophotonic properties and biocompatibility with human tissues make it appealing for use in biomedical applications. Concerns related to limited oil supply, associated political issues, and public anxiety with landfills saturated with nonbiodegradable materials fuel the need for economical industrial PHB production (Lee, 1996; Poirier, 1999; Coats, 2005).

The Problem with PHB

PHA research has increased in an effort to understand its potential, as well as to counteract some of the issues preventing its widespread use. Because of its high cost, PHB has been used mostly for specialized medical applications, including bone fixation, drug delivery systems and degradable sutures (Knowles, 1993: Kose, 2004; Holmes, 1985: Chen, 2005), and less for commercial packaging.

High expense is the primary factor preventing industrial scale PHB production and commercialization. A low estimate for the cost of PHB production is $3-5/kg PHB versus $1/kg petroleum-based plastics (Choi, 1997). Some of the factors that contribute to this cost difference are reactor operation, substrate costs, and the extraction and downstream processing procedures (Coats 2005). There are many techniques that have been researched, or are currently being researched, to eliminate some of these major costs. Production methods for PHB involve the use of recombinant microorganisms, crops of transgenic PHB producing plants, and fermentation with naturally occurring strains of PHB accumulating organisms (Poirier, 1999).

For this project, we attempted to minimize PHB production cost by considering the PHB yield, as this can drastically affect the polymer expense. In one example, a study showed that a PHB yield reduction from 88.3% CDW to 50% CDW contributed to a cost discrepancy of $1.6/kg (Lee SY, 1998). Recombinant E. coli cells harboring PHB production genes from C. necator were used in this project because it has been shown that these cells are capable of accumulating PHB in excess of 90% CDW. The goal of this study was to reduce the cost of industrial PHB production by creating a rapid biosensor system for determining the point when PHB accumulation is at its maximum, thereby optimizing polymer extraction.

PHB Metabolic Pathways

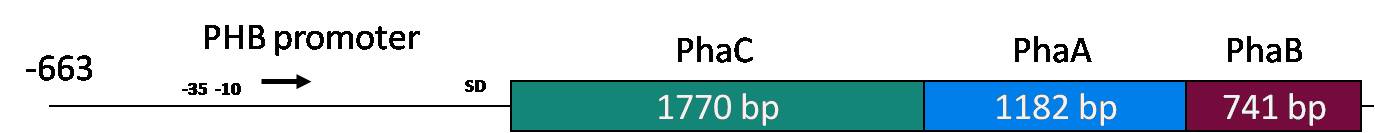

The metabolic pathway for PHB accumulation in C. necator involves three biosynthetic enzymes. The figure below shows the structure of the PHB operon. Transcription of these genes occurs under conditions of noncarbon nutrient limitation.

Metabolic Pathway

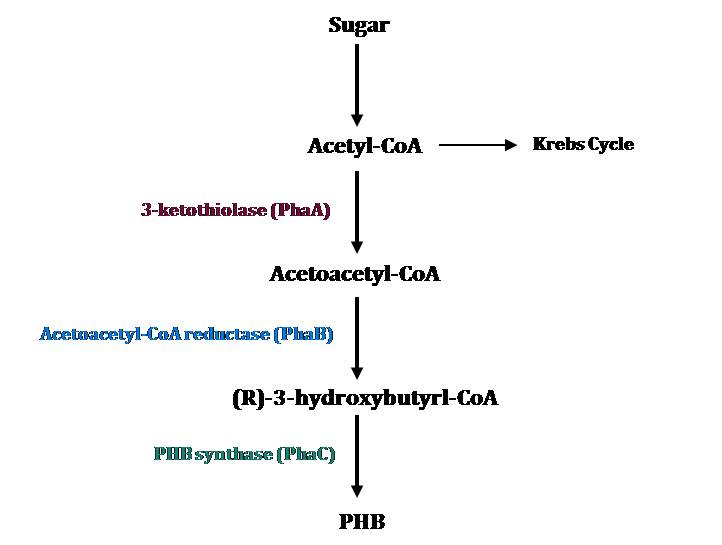

The metabolic pathway for PHB accumulation is depicted in the figure on the left and consists of three major steps (Verlinden, 2007).

1. 3-ketothiolase (PhaA) produces acetoacetyl-CoA by joining two molecules of acetyl-CoA

2. Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB) promotes the reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA by NADH to 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA.

3. 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA is polymerized by PHB synthase (PhaC)

Acetyl-coenzyme-A (acetyl-CoA) is a PHB precursor that is naturally produced by these bacteria.

Green Fluorescent Protein

GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) is a protein originally isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, fluorescing when exposed to ultraviolet light. GFP is used as a tag, attached to proteins as a marker. Only those cells in which the tagged gene is expressed will fluoresce. In such a way GFP acts as a positive marker of tranformation. In our laboratory, GFP is used as an expression reporter of PHB. The GFP gene primarily used in this project was GFP E0240 BioBrick supplied by iGEM.

Methods

Organisms

Two organisms were used as genetic sources for PHB: Cupriavidus necator and an Escherichia coli strain containing the PHB operon in a pBluescript vector. The E. coli strain proved to be easier to use as a PCR template because of the ability to miniprep the plasmid DNA to use as more pure template.

Transformations

A total of 26 transformations were successfully performed to become familiarized with the transformation process and to test different promoters and reporters. Three of these transformations were GPF plasmids with promoters of different strengths, taken from the iGEM promoter-testing kit. Another three of these transformations were BioBrick transformations. Top 10 competent E. coli cells were used for all transformations, excluding one transformation using a toxin-resistant strain.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

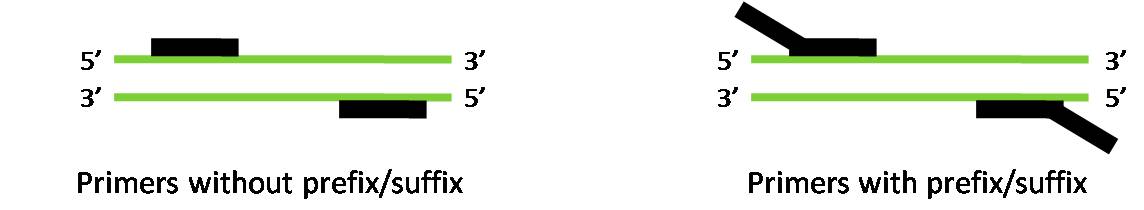

Nine sequences were targeted out of the PHB operon for amplification. Five PCR targets were promoter sequences: 5’phaCproF/ATG R, 5’phaCproF/SD R, 5’phaCproF/TC R, -35F/ATG R, and -35F/TC R. Four PCR targets were from phaCAB gene complex: phaC, phaA, phaB, and phaCAB. A variety of annealing temperatures and Mg++ concentrations were tried, and it was found that 60˚C annealing temperature and 12% (v/v) Mg++ concentration were optimal. Two sets of primers were used: those without the BioBrick prefix and suffix attached and those with them already attached. The use of the PCR conditions just described enabled the use of the latter, saving subsequent ligations from needing to be done. Such PCR reactions were successful with all of the promoter regions and the phaB gene.

PCR Primers

Two sets of primers were created for PCR – those containing the prefix and suffix restriction sites and those without the prefix and suffix. The primers with the prefix and suffix already attached were designed to save subsequent ligations of the prefix and suffix from needing to be done. The primers without the prefix and suffix had greater affinity to the DNA template than those with them because of the absence of non-binding segments.

The figure below illustrates the greater binding affinity for primers without the prefix and suffix.

Vector Selection

Two plasmids were primarily used during the course of the project – pSB1A3 and pSB3K3. pSB1A3 is an ampicillin-resistant plasmid, 2157 base pairs long, that was used as the vector for all submitted BioBricks. pSB3K3 is a Kanamycin-resistant plasmid, 2750 base pairs long, that was used for promoter testing in accordance with the iGEM promoter- testing protocol.

Gel Electrophoresis

DNA gel electrophoresis, 1% w/v agarose, was used for analysis of PCR products, digested plasmid, and ligation constructs. The cross-linked matrix formed by agarose gel separates DNA by size when an electrical field is created across the gel. DNA migrates toward the positive electrical anode by electromotive force because of the natural negative charge of the DNA’s phosphate-sugar backbone. Ethidium bromide and Sybr Green dyes selectively bind DNA and were used in various experiments for band observation. Select PCR, plasmid, and ligation products were excised from agarose gels for purification and further processing.

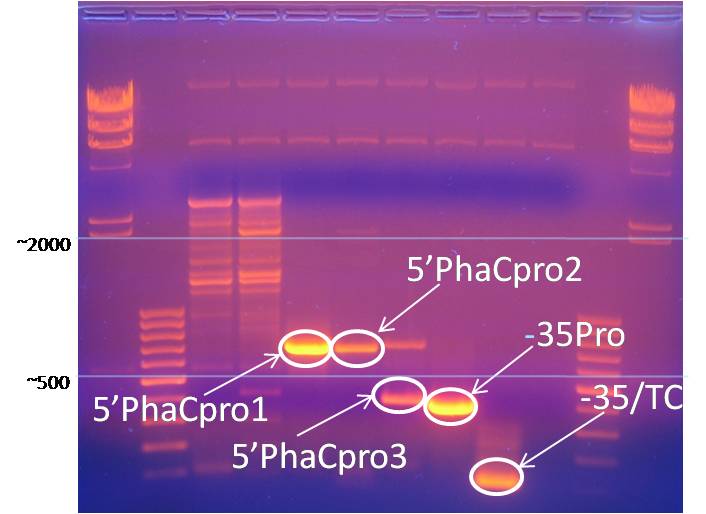

Promoter PCR products were obtained through gel electrophoresis and a DNA purification kit. The image below shows a gels used to isolate these promoter regions.

GFP Correlation

After some deliberation, it was decided to use Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as the PHB marker. Two methods were proposed to carry this through. The first method would involve ligating the GFP gene into the PHB operon, thereby allowing simultaneous transcription of the PHB-biosynthetic and GFP genes, regulated by the PHB-induction machinery. The second method would involve separate PHB-biosynthetic and GFP regions – either by bacteria containing two plasmids, one with the PHB operon and one with the GFP operon, or by using a plasmid containing both operons but in separate locations on the plasmid. In order to test for the most effective regions of the PHB promoter, five regions of the promoter were targeted for PCR (see PCR section). It was decided to then test these promoters using the iGEM promoter testing kit, testing for GFP expression in the pSB3K3 plasmid. A spectrofluorometer was used for fluorescence measurement.

PHB Promoter Testing

PHB promoter testing was planned according to the iGEM promoter testing kit instructions. Briefly, this kit contains three identical GFP-containing plasmids which only differ in their promoter strength (dubbed "weak," "medium," or "strong"). The kit outlined a method of preparing a promoterless GFP gene in a Kanamycin-resistant plasmid (pSB3K3). Our objective was to ligate our BioBrick promoter regions into this plasmid and compare them to the weak, medium, and strong promoter standards using a spectrofluorometer.

BioBrick Part Assembly

After performing PCR using suffix/prefix-containing primers, PCR products were digested with EcoR1 and Pst1. The samples were then run out on an electrophoresis gel, and the correctly-sized bands were cut out from the gel. The DNA was extracted using a Qiagen gel-purification kit. These inserts were then ligated into miniprepped pSB1A3 plasmid which had already been EcoR1/Pst1 digested and purified from a gel. These ligations were then transformed into Top 10 competent E. coli cells on Ampicillin-containing agar plates. If the transformations were successful, Amp-containing liquid cultures were made from which glycerol stocks and DNA minipreps were prepared. Portions of the minipreps were digested with restriction enzymes from the prefix and the suffix, and the samples were run out on a gel to test for expected insert and vector lengths. If this test was passed, the sample was submitted as a BioBrick.

Results

Detected intracellular PHB

- 1H-NMR was successfully used to detect PHB accumulation in recombinant E. coli harboring the PHB-biosynthetic genes from C. necator.

Successfully Created BioBricks

- 5’phaCpro1 in pSB1A3

- 5’phaCpro3 in pSB1A3

- -35/TC in psB1A3

BioBricks awaiting ligation

- PhaB in pSB1A3

BioBricks in earlier stages of completion:

- 5’phaCpro2 in pSB1A3

- -35Pro in pSB1A3

- PhaA in pSB1A3

- PhaC in pSB1A3

- PhaCAB in pSB1A3

Conclusions

PHB accumulation needs to be monitored.

Polyhydroxybutyrate has great potential as a renewable, biodegradable plastic. At present, extraction methods of PHB are more costly than production methods for petrochemically-derived plastics, making higher extraction efficiency a necessity. Using a genetic marker to identify optimal extraction time will reduce these costs by providing maximum PHB yields.

GFP could be an effective marker.

Green fluorescent protein has been shown to be an effective genetic marker since its discovery in 1968. Since it's genetic sequence and optical properties have been well studied, the USU iGEM team felt GFP would provide acceptable indication of PHB expression.

The USU iGEM team has constructed some necessary BioBricks.

The effective use of GFP as an expression marker will depend on sufficient understanding of both the PHB promoter and PhaCAB cassette. The USU iGEM team has made progress in both of these areas and has created three BioBricks from the promoter region.

References

1.Chen GQ, Wu Q. 2005. The application of polyhydroxyalkanoates as tissue engineering materials. Biomaterials. 26:6565-6578

2. Doi Y, Kunioka M, Nakamura Y, Soga K. 1986. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies on poly(B-hydroxybutyrate) and a copolyester of B-hydroxybutyrate and B-hydroxyvalerate isolated from Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Macromolecules. 19:2860-2864

3. Endy D. 2005. Foundations for engineering biology. Nature. 438(7067):449-53

4. International Genetically Engineered Machines competition. 15 Jun 2008. 26 Jul 2008. <https://igem.org>

5. Holmes PA. 1985. Applications of PHB – a microbially produced biodegradable thermoplastic. Physics in technology. 16:32-36

6. Kang Z, Wang Q, and H Zhang. 2008. Construction of a stress-induced system in Escherichia coli for efficient polyhydroxyalkanoates production. Biotechnological Products and Process Engineering. 79:203-208

7. Knight TF. 2003. Idempotent Vector Design for Standard Assembly of BioBricks. Tech. rep., MIT Synthetic Biology Working Group Technical Reports

8. Lee SY, Choi J. 1999. Metabolic engineering strategies for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, a family of biodegradable polymers. eds. S. Y. Lee and E. T. Papoutsakis. Marcel Dekker, USA, pp. 113-151

9. Lee SY. 1996. Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 49:1-14

10. Poirier Y. 1999. Green chemistry yields a better plastic. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:960-961

11. Registry of Standard Biological Parts. 17 Oct 2008. 26 Jul 2008 <http://partsregistry.org/Main_Page>

12. Shetty RP, Endy D, and TF Knight Jr. 2008. Engineering BioBrick vectors from BioBrick parts. Journal of Biological Engineering. 2:5

13.Schubert P, Kruger N, and Steinbuchel A. 1991. Molecular analysis of the Alcaligenes eutrophus poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) biosynthetic operon: identification of the N terminus of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) synthase and identification of the promoter. The Journal of Bacteriology. 173(1): 168-175

15. Verlindin RAJ, Hill DJ, Kenward MA, Williams CD, and I Radecka. 2007. Bacterial synthesis of biodegradable Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Journal of Applied Microbiology 102:1437–1449

"

"