Team:Caltech/Project/Oxidative Burst

From 2008.igem.org

|

People

|

Pathogen Defense by Oxidative Burst

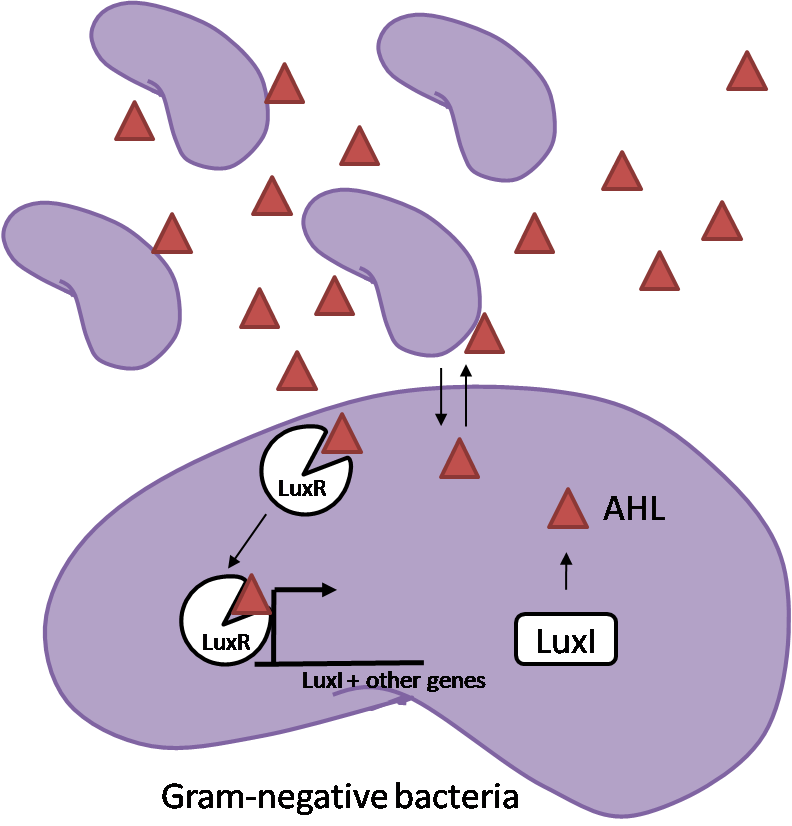

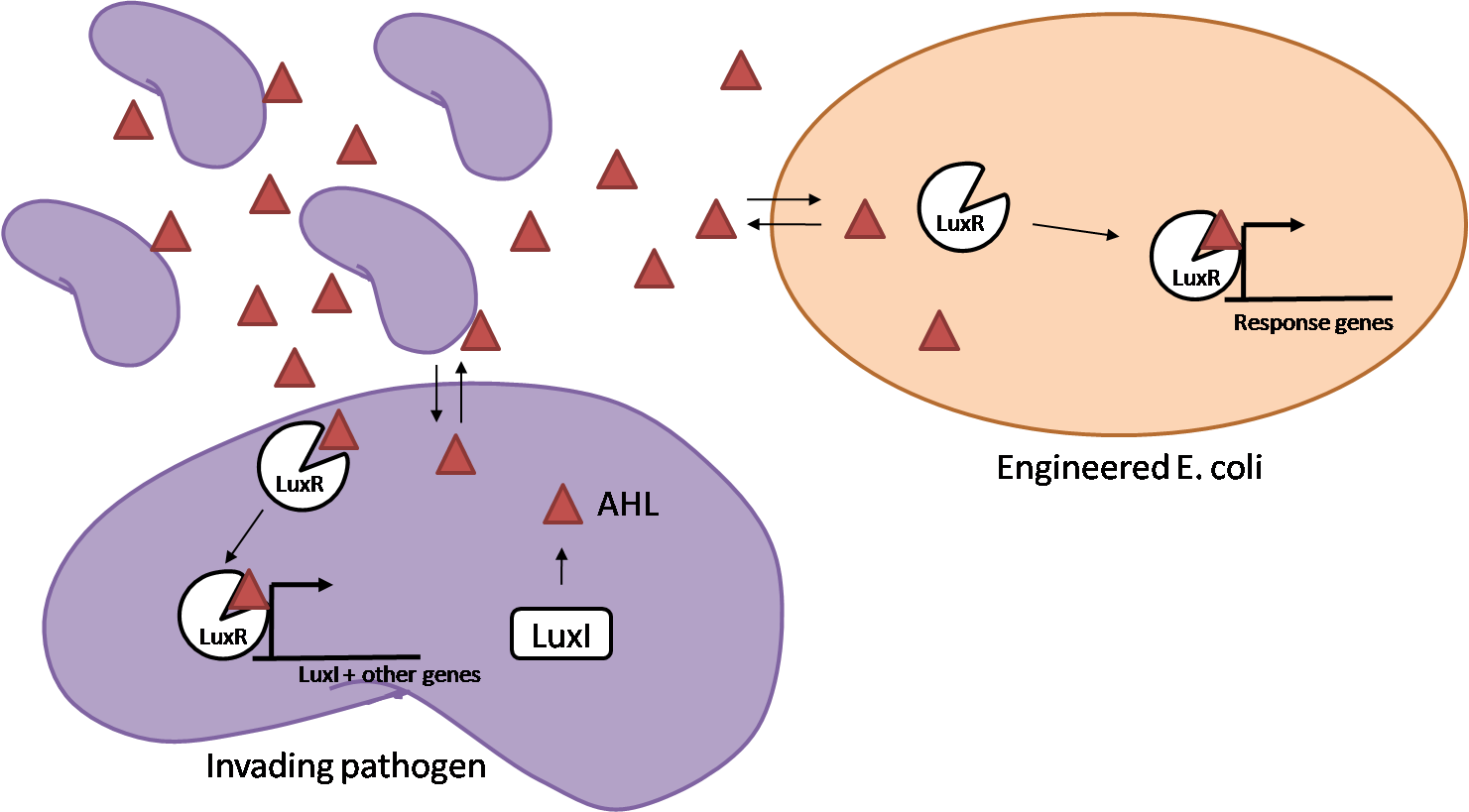

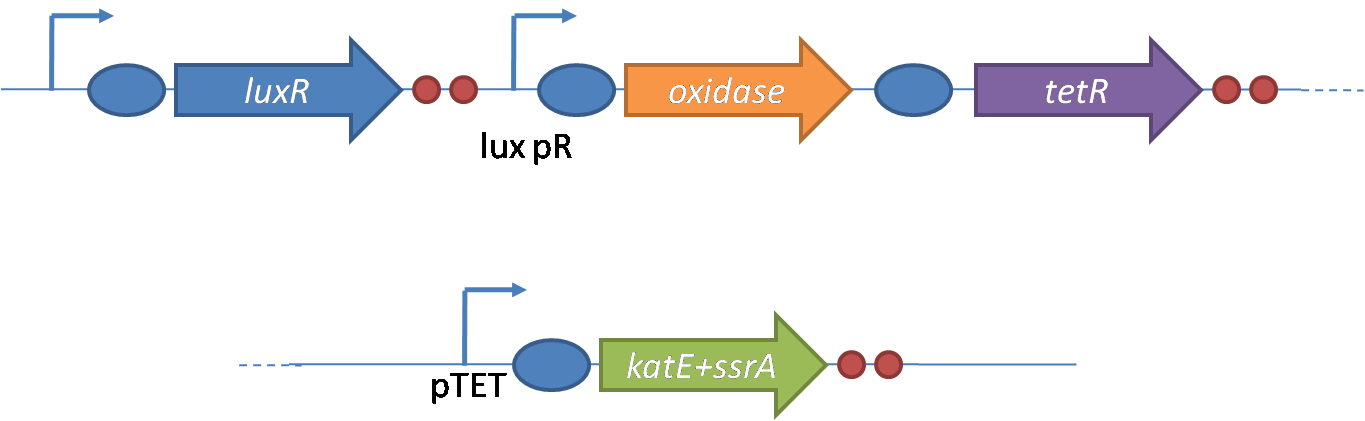

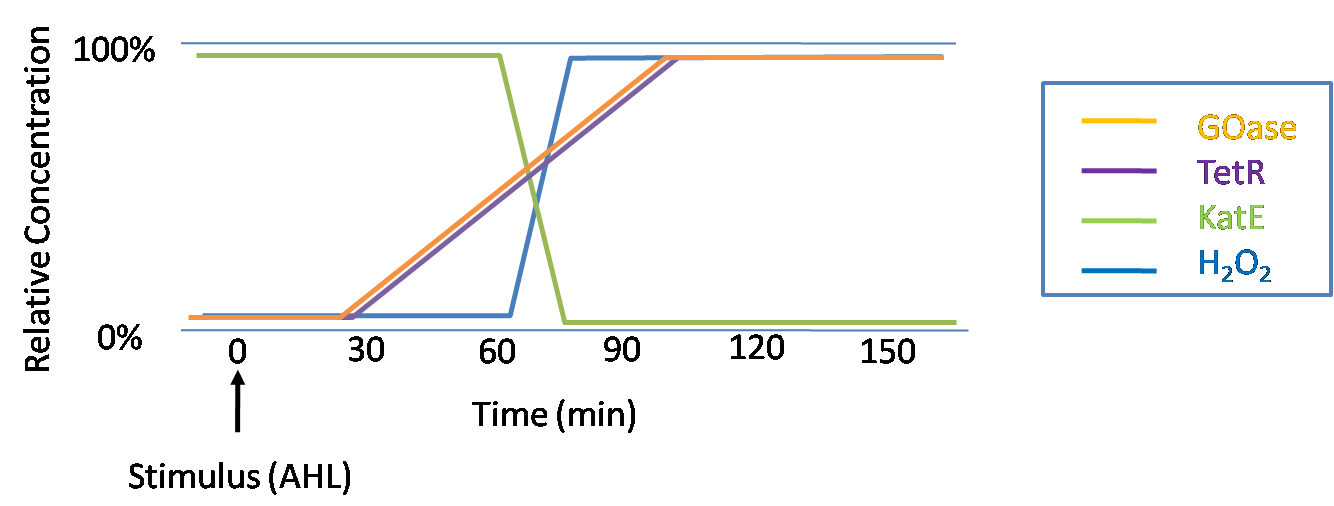

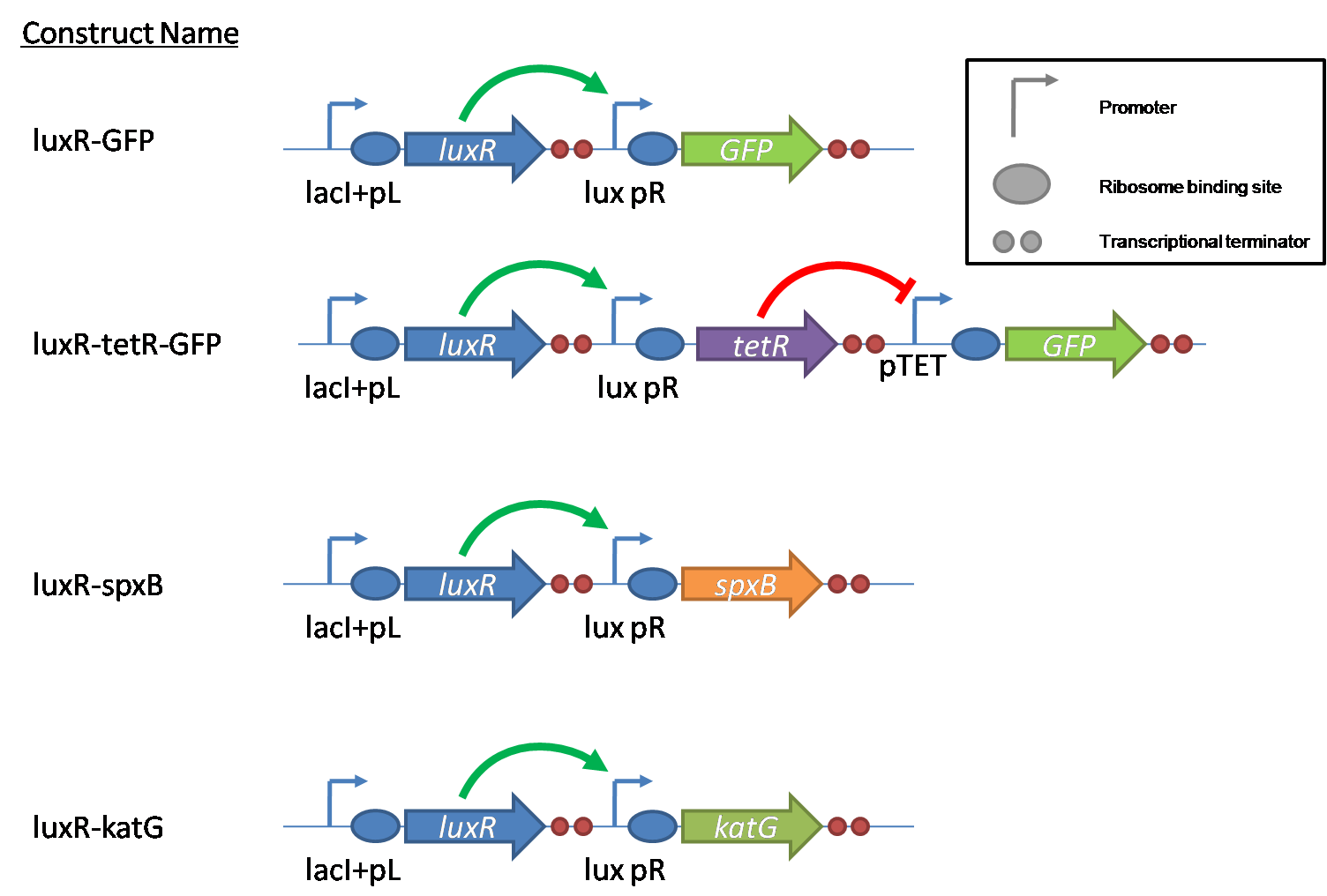

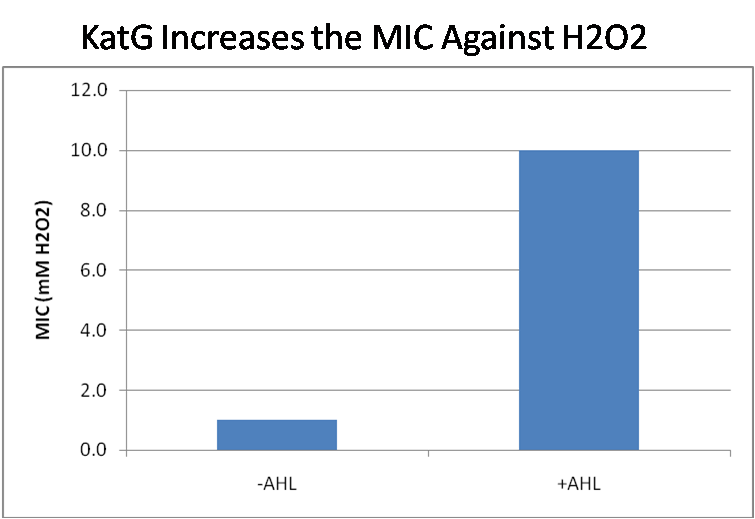

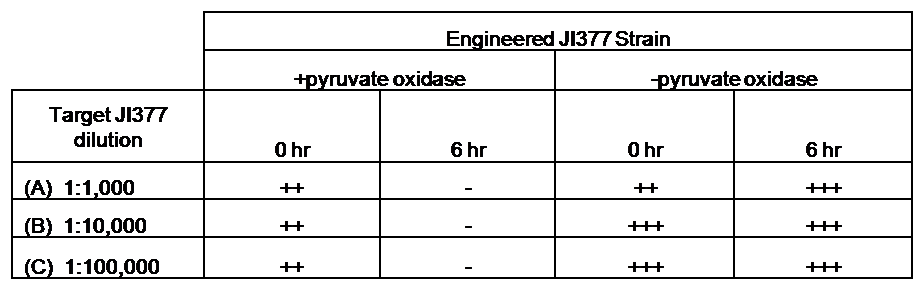

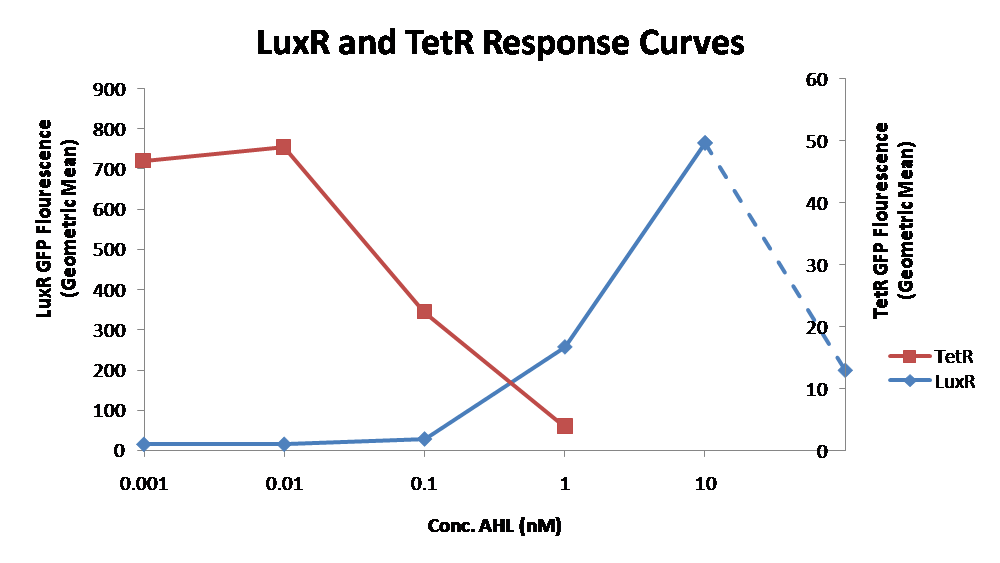

IntroductionIn order to help guard against infections of the gut, we wish to engineer a strain of E. coli capable of killing bacterial pathogens. White blood cells called neutrophils are already very efficient at killing bacteria. Neutrophils kill bacteria by bombardment it with a variety of reactive oxygen species including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydrochlorous acid. The reactive oxygen species kill the bacteria by shredding biological molecules by way of their potent oxidizing properties. However neutrophils do not to migrate to the large intestinal lumen where pathogens can reside. Because bacteria are well adapted to live in the gut, this project’s goal is to engineer a strain of E. coli to detect and kill invading bacterial pathogens by means of a sudden burst of hydrogen peroxide. DetectionBacteria are able to communicate between individuals of the same species by way of quorum sensing. Small molecules serve as the signal between individual cells. Gram negative bacteria use acylhomoserine lactones (AHL), which can freely diffuse across the cell membrane. The quorum sensing machinery relies in two enzymes, LuxI, an AHL producer, and LuxR, an AHL-dependent transcriptional activator. Figure 1 illustrates how the quorum sensing system works. In isolation, each bacterium constitutively produces a small amount of AHL, which quickly diffuses into the surroundings. If other bacteria of the same species are also nearby, the AHL will diffuse across their membrane where it will bind to LuxR. LuxR activates transcription of several genes, including luxI. A positive feedback loop is created, in which more AHL induces more LuxI, which in turn produces more AHL. Each species of gram negative bacteria produces a unique AHL, requiring unique LuxI and LuxR proteins, and so avoids crosstalk between species. A group of bacteria can thus toggle between an “off” state and an “on” state by using quorum sensing. Our engineered strain will not participate directly in quorum sensing, but instead will eavesdrop on the conversation. It will be engineered to constitutively express a LuxR able to detect a species AHL. By taking advantage of the specificity of quorum sensing, our engineered strain will be able to be tuned to specifically respond to a variety of bacterial pathogens. Once the AHL is bound, LuxR will activate a set of genes which will lead to the overproduction of hydrogen peroxide, killing the invading cell. ResponseAfter sensing the presence of an invading pathogen, we want to engineer our E. coli to produce lethal amounts of hydrogen peroxide relatively quickly. We are not concerned with having the engineered E. coli survive either, as it is reasonable to assume that there are “unactivated” cells far away from the pathogen that could sustain the population. Even if all of the oxidative burst cells were wiped out, the population could be regenerated. In combination with the population variation project, the "master cell line" would differentiate into the oxidative burst state, thus reseeding the population. After LuxR binds AHL, it will activate transcription of pyruvate oxidase, which uses pyruvate to produce hydrogen peroxide in the following reaction: Pyruvate + phosphate + O2 --> H2O2 + CO2 + acetyl phosphate Streptococcus pneumoniae naturally uses pyruvate oxidase to kill off competing bacteria when infecting the lungs. Having already known its activity and antibacterial properties in vivo, pyruvate oxidase was an attract oxidase with which to work. Even though our activated engineered cells will eventually die from their oxidative burst, we want them to survive long enough to produce large amounts of the oxidase so they can produce large amounts of hydrogen peroxide. If the cells were left to produce hydrogen peroxide without any protection, they would produce just enough to be cytotoxic and then fissle, killing only themselves and little else. To avoid this problem, an E. coli catalase will be constitutively expressed, and then turned off shortly after pyruvate oxidase expression is triggered. We’re accomplishing this by putting katG (on of two E. coli catalase genes) behind the tetR sensitive promoter (tetR P) and having tetR co-transciptionally expressed with the oxidase. The time it takes for tetR to accumulate in the cell provides the delay in repressing katG expression. To ensure katG is rapidly cleared from the cells, it has a C-terminal ssrA degradation tag, which should reduce the protein’s half life to the order of minutes. In this way, the cell can be temporarily protected from hydrogen peroxide, but large amounts can accumulate before the substrate is exhausted.The final strain will have deletions of both catalases, ensuring no complementation. System DesignThe entire system will be engineered onto a high copy plasmid in E. coli as seen in Figure 3. Promoters are shown as bent, thin arrows, genes as thick arrows, ribosome binding sites as blue ovals, and a double transcriptional terminator as two red circles. Initially, the system will function independently, with luxR under a constitutive promoter. Later, luxR will be put under the control of a recombinase system that will only turn on the pathway randomly in a subset of cells. This will be one of three fates the master strain will be able to differenciate into. For more information, visit the population variation page. An ideal system would behave as outlined in Figure 4. It shows the relative abundances of the proteins and molecules used in the system. It is only meant to show if a particular species is relatively high or low, not its absolute concentration. ResultsConstructsThe constructs shown in figure X were made using the standard assembly method. They were made to test the various regulatory elements and the functionality of the oxidase and catalase. Characterization of LuxR Inducer Figure X - Characterization of LuxR inducer and TetR inverter by flow cytometry. The figure shows the fluorescence of GFP in the constructs luxR-GFP and luxR-tetR-GFP. The left axis corresponds to the LuxR data and the right axis corresponds to the TetR data. At 100 nM AHL, cells with the luxR-GFP construct grew very poorly. The luxR inducer was characterized using the luxR-GFP construct. GFP provides a relative gauge of expression levels of SpxB in the final construct. The cultures were grown over a range of AHL concentrations and analyzed by flow cytometery. Figure 4 shows the LuxR inducer behaves as expected. It shows tight repression in the uninduced state, and begins to show significant expression at 1nM AHL. There is a 50 fold difference between the uninduced and fully induced (10nM AHL) state. The sudden drop at 100nM AHL is explained by the fact that these cells grew very poorly, possibly the result of toxic proteins loads. The LuxR inducer functions well if the concentration of AHL is kept below 10nM. Characterization of TetR InverterThe TetR inverter was characterized by using a luxR-tetR-GFP construct. In this context, GFP provides a relative gauge of expression levels of KatG in the final construct. Figure X shows the tetracycline inverter behaved as expected. At high concentrations of AHL, the TetR inverter shows near full repression, as compared to the lower concentrations of AHL. Similar to the LuxR inducer, the TetR inverter showed a 50 fold difference in expression between the uninduced (low AHL) and induced (high AHL) states. However the absolute maximum level of expression from the TetR inverter was much lower than that from the LuxR inducer (compare the scale of the left TetR axis to the scale of the left LuxR axis). The low expression levels can be explained by the leakiness of the LuxR promoter, resulting in a basal level of repression from the TetR inverter. The low expression level is advantageous for the engineered E. coli because catalase is a very efficient scavenger of hydrogen peroxide. The low expression level ensures there is enough KatG to buffer any leaky pyruvate oxidase expression, yet still clear quickly from the cytoplasm. Additionally, in the uninduced state there should be extremely low levels of KatG. The LAA degradation tag should reduce KatG levels even further. Production of Hydrogen PeroxideJI377 cells expressing pyruvate oxidase behind the LuxR inducer were able to produce significant amounts of hydrogen peroxide when cultured in rich media, reaching a maximum of 800 µM H2O2 in 2 hours (see figure 4).This is significant because the engineered cells can produce more than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for hydrogen peroxide of some human pathogens (4). The decline in hydrogen peroxide concentration after the peak is explained by the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with the SOC media, since H2O2 has a half life of about 3.5 hours in SOC (data not shown). The most surprising finding was that the cells began expressing hydrogen peroxide a full hour before they were induced with AHL. The current hypothesis is that some component of the rich SOC media mimicked AHL and activated LuxR. Uninduced expression from LuxR was also observed when culturing cell transformed with the luxR-GFP construct in LB media, as cell pellets were visibly green. However, no such autoinduction occurred in the defined minimal media M9. It would be interesting to see if LuxR spontaneously activates expression in a rich defined media, such as Neidhardt. However, the significant finding is that pyruvate oxidase is capable of producing significant amounts of hydrogen peroxide in a short amount of time in vivo. Functionality of KatGFunctional expression of KatG from the luxR-katG construct protects cells from hydrogen peroxide. Figure 5 shows that expression of the KatG +LAA degradation tag in catalase deficient cells (JI377) increases their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by an order of magnitude. It is significant in that the MIC range of 3.0 - 10.0 mM H2O2 is well above to the MIC value of wild type E. coli (MIC = 0.8 uM). Even with a degradation tag, KatG is still functional and is sufficient to protect the cell from exogenous hydrogen peroxide. In an uninduced state, KatG will be able to buffer the engineered cell from leaky hydrogen peroxide production and should be degraded on the order of minutes because of the LAA tag. However in the final engineered JI377, KatG will be expressed from behind the tetracycline inverter, not the LuxR system. Further tests will be necessary to ensure that the reduced expression levels from tetracycline inverter still produce enough KatG to raise the MIC of JI377. The important result is that KatG +LAA is functionally expressed and is able to raise the MIC of JI377. Coculture AssayFinally, we wanted to see if the engineered JI377 cells could directly kill or inhibit the growth of a competing JI377 strain (due to time constraints, only JI377 with a luxR-spxB construct could be tested). We carried out co-culture assays in which varying amounts of the target strain were introduced to a heavy (OD600 of ~0.8) culture of the engineered strain, and incubated the co-culture for 6 hours after induction with AHL. Introducing the target strain to a dense population of our engineered E. coli was meant to mimic the situation in the gut where in invading pathogen will face an already established culture of engineered E. coli. Survival of the target strain was assayed by a colony forming unit (CFU) count both immediately upon introduction and after 6 hours of co-culturing. Table 1 summarizes the results. The CFU data show that the engineered strain was able to kill the target JI377 strain, while the target strain was unaffected or was able to grow in co-cultures with the negative control (JI377 with no pyruvate oxidase). Current Progress

References |

"

"