Team:Caltech/Project/Lactose intolerance

From 2008.igem.org

|

People

|

Curing Lactose Intolerance

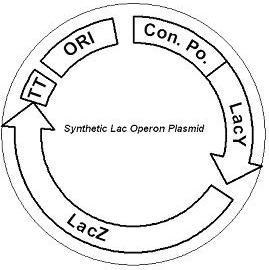

IntroductionThe gut flora of our digestive tract contains microorganisms that perform various useful functions for their hosts. Examples of such functions include growth inhibition of harmful microorganisms1, defense against the causes of many forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease2, and the fermentation of carbohydrates and other molecules the human body cannot normally digest. Some bacterial strains, including the E. coli strain ‘Nissle 1917’, can persist in the gut of mice for months. Engineering these bacteria provide a new platform to treat various human diseases. Lactose intolerance is characterized by the inability to break down lactose in the small intestine. The undigested lactose instead passes to the large intestine, leading to two negative processes: osmotic imbalance and bacterial fermentation. High lactose levels raise the osmolarity of the colon, causing diarrhea. In addition, gut microbes metabolize the lactose into methane gas, causing abdominal pain. Both problems must be addressed in order to fully treat lactose intolerance. If we simply have our strain metabolize lactose, another strain will further ferment the byproducts, resulting in the same side effects. Instead, we have our engineered strain allow the host to uptake lactose, clearing the sugar from the colon. To do this, we have engineered the ‘Nissle 1917’ strain to release ß-galactosidase, an enzyme that cleaves lactose into glucose and galactose. Since protein secretion is difficult in E. coli, our cells were engineered to lyse in order to release ß-galactosidase. However, lysis must occur only when lactose is present in the gut. Therefore, the cells also express a mutant lactose permease, allowing the strain to sense lactose in all conditions. System DesignLactose RegulatorThe first plasmid consists of a synthetic lactose operon under strong constitutive expression (Fig. 1). Our synthetic lactose operon encodes the ß-galactosidase LacZ and a mutant form of the lactose permease LacY. LacY is a membrane protein that actively transports lactose into the cell. Since most membrane proteins are toxic when overexpressed, we optimized our system to express appropriate levels of LacY without killing the cell. In the end, we want to express as much ß-galactosidase as we can to cleave as much lactose present in the large intestine.

The human gut is an unpredictable environment, and we wish our engineered cells to behave reliably despite this variability. E. coli are unable to uptake lactose in the presence of glucose, a phenomenon known as carbon catabolite repression. Catabolite repression is mediated by Enzyme IIA Glucose (IIAGluc), which inhibits the uptake of lactose in the presence of glucose by binding to LacY3. Previous research has identified various LacY mutations that prevent this inhibition and achieve increased uptake of lactose in the presence of glucose4.

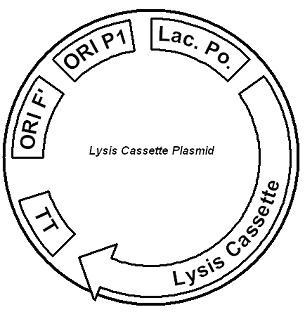

Lactose-Induced Lysis The lysis cassette plasmid acts as a lactose sensor. Intracellular lactose accumulation induces overexpression of the lysis cassette. Lactose inhibits binding of the LacI repressor to the promoter and P1 high copy origin of replication. A mutated holin gene in the lysis cassette allows faster lysis times. The second plasmid contains lactose inducible expression of λ phage lysis genes (Fig. 2). To release ß-galactosidase, the cells will lyse when enough lactose is present in the cell to induce the expression of the lysis genes. Absent any stimulus, the plasmid containing the lysis genes remains at low copy but switches to high copy when induced with lactose. In addition, the lysis genes are placed behind lactose-inducible promoters. It is important that the lactose-inducible promoter be tightly regulated, since leaky expression will cause spontaneous lysis6.

Using wild type λ phage lysis genes, lysis occurs 40-45 minutes after induction by lactose. Decreasing the lag time will reduce the extent of lactose fermentation and therefore produce fewer deleterious effects. Previous research has uncovered mutations that shorten the lysis time to approximately 10-15 minutes5, and these mutations will be incorporated into our final construct.

ResultsLactose RegulatorIn the first plasmid, it was discovered that LacY is toxic when overexpressed. To determine safe expression levels, constructs were built with varying levels of LacY expression. Six plasmids were built from combinations of three different promoters and two different ribosome binding sites (Fig. 3). The cells died when expressing the strongest and medium strength promoters along with the strongest ribosome binding site. We decided to express LacZ by combining the weakest ribosome binding site with the strongest constitutive promoter, preventing LacY toxicity while expressing LacZ in large quantities. As mentioned earlier, our cells had to overcome carbon catabolite repression. Various mutations, including the insertion of two histidyl residues between amino acids S194 and A195 (ref 4) in the LacY gene, prevent the inhibition by IIAGluc. These insertions have been made, but we have not had enough time to test it. ß-galactosidase assays were used to quantify our data from our lactose regulator. The assay was performed twice on the synthetic network containing the lactose operon (Fig. 4). The first assay was performed on a strain containing the plasmid lacking the strong constitutive promoter. This assay was performed to simulate the eventual system regulation. Our completed project will be under the expression of a promoter controlled by the FimE recombinase. The promoter will initially be pointing away from our synthetic lac operon and will be inverted to face the operon when the system is turned on. We saw significant levels of ß-galactosidase, a surprising result since the plasmid lacked a promoter. These levels are likely due to spurious transcription amplified by our strong ribosome binding site and high copy plasmid. We then repeated the assay one more time with the strong constitutive promoter to observe the dynamic range of LacZ expression in this system. |

"

"