Team:Newcastle University/Bacillus subtilis

From 2008.igem.org

Newcastle University

GOLD MEDAL WINNER 2008

| Home | Team | Original Aims | Software | Modelling | Proof of Concept Brick | Wet Lab | Conclusions |

|---|

Home >> Original Aims >> Bacillus subtilis

Advantages of using B. subtilis

There are several reasons why we chose to use B. subtilis, as opposed to E. coli as our chassis.

Pathogenesis

B. subtilis is categorised under Biohazard Level 1- i.e it is a minimum risk bacteria. As a result of not being considered a human pathogen, the only necessary precautions to be implicated include using gloves, hand-washing, and autoclaving equipment. This saves time and money.

Gram-Positive

The Gram stain technique is based on the ability of a bacterial cell wall to retain a crystal violet dye- allowing us to differentiate between two major cell wall types:

- Gram negative cell walls have a lower percentage of peptidoglycan. Gram-negative bacteria also have an additional outer membrane containing lipids, separated from the cell wall by the periplasmic space.

- Gram positive cell walls contain a relatively large amount of peptidoglycan (up to 90%) but lower lipid content. This stains purple upon addition of crystal violet dye, whereas the wall of a gram negative bacteria will only stain pink.

After decolorisation, Gram-positive cells remain purple and Gram-negative cells lose their purple colour. When counterstain is applied, Gram-negative bacteria turn red.

For a tutorial on Gram staining see: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/dental/oralbiol/oralenv/tutorials/gramstain.htm

B. subtilis is a gram-positive bacterium and therefore contains only a single membrane. Consequently, they absorb substances better than E.coli, and this is ideal for our project.

Transformation

B. subtilis has the ability to take up exogenous DNA from the surrounding medium and integrate it in their genome. This natural competency can be tightly regulated and induced in the lab by nutritional shortages using starvation medium.

This makes transformation easier, as competence comes naturally to B.subtilis.

Sporulation

During times of nutritional stress, B.subtilis cells produce an endospore which enables it to withstand extreme conditions such as high temperatures and salt concentrations. The purpose of this is to allow the bacterium to survive in the unfavourable environment until conditions return back to normal. Prior to the decision to produce the spore the bacterium may take up DNA from the surrounding medium.

This means that B.subtilis can be easily stored and transported without damaging the cells and their ability to differentiate.

Using a B. subtilis chassis is different to using an E. coli chassis

Although B. subtilis has many clear benefits in its usage, Gram-positive bacteria are generally relatively poorly characterised and consequently can be unpredictable to work with. Nevertheless, B. subtilis is one of the best known Gram-positives. This page intends to cover some issues about working with this bacterium.

In this project, we used B. subtilis 168 (Bs168). This is a strain which is mutated in the trp operon and subsequently must have tryptophan present in its growth medium as it cannot synthesise this essential amino acid. The inability to synthesise tryptophan means that Bs168 is nutrient-inducible (a factor that can be exploited when introducing exogenous DNA).

Genetic Transformation

The transformation procedures in E. coli and B. subtilis are very different. The E. coli strains we were working with (TOP10 and DH5α) were already competent to take up exogenous DNA, or made competent chemically, and therefore require only basic preparation before transformation. This briefly consists of adding the DNA to the cells and incubating them on ice, then heat shocking and adding LB before incubating again at 37°C.

In contrast, B. subtilis cells must be induced to take up foreign DNA. Research has shown that when B. subtilis “encounters nutrient limitations and enters the stationary growth phase, it can engage in multiple adaptation strategies such as…uptake of exogenous DNA (competence)” 1. It is therefore important to carefully control the growth phase and nutrient availability in the B. subtilis culture prior to transformation. We used the protocol below to achieve this.

One of the main advantages of using B. subtilis is that it is naturally competent for transformation. When bacteria are in the stationary growth phase and are nutrient-starved, the cells begin to transcribe high levels of a tetramic protein called ComK, a transcription factor that activates over 100 genes (“including those essential for DNA binding and uptake” 2. The competency of the cells to take up exogenous DNA is transient, and therefore observing correct timings in the transformation protocol is very important in increasing the population of competent cells.

Protocol for Genetic Transformation into B. subtilis

- Prepare two conical shake flasks of the following medium:

- 10mL SMM ('Spizizen salts')

- 125 µl sol E (40% glucose)

- 100 µl tryptophan

- 60 µl sol F (1M MgSO4)

- 10 µl casamino acid (CAA)

- 5µl ammonium iron

- To one flask add 2mL liquid culture cells.

- Incubate both flasks at 37°C overnight. (It is important that the flask without cells in is kept at 37°C also as this is the dilution medium and must be pre-warmed at the same temperature as the culture to avoid temperature stress of the cells.)

- Add 500 µl overnight culture to the pre-warmed dilution medium and leave to incubate at 37 °C for 3 hours. (This allows the cells to enter the stationary growth phase.)

- Add 10mL SMM, 125 µl sol E and 60 µl sol F to the dilute culture and leave to incubate at 37°C for a further 2 hours. (This starves the cells of amino acids such as tryptophan and CAA.)

Transfer 10µl plasmid to be transformed into a 2mL tube. Add 400µl nutrient-starved cell culture and mix by inverting the tube five times.

- Incubate at 37°C whilst shaking for 1 hour. (The tubes must be laid on their side to properly aerate the medium. To do this, tape the tubes to the rack and lay it on its side to prevent the tubes falling out whilst shaking.)

- Plate cells on nutrient agar.

Temperature Sensitivity

Unlike E. coli, B. subtilis is very temperature sensitive and sudden changes in temperature can be detrimental to it. When culturing, the cells should be kept at their 37°C optimum. We cultured all our colonies in a 37°C culture room. This way we could perform all pipetting and diluting of cells without changing their temperature.

Oxygen Requirements

B. subtilis is a strict aerobe and also requires much more oxygen than E. coli. If they become anoxic they will quickly die. Therefore it is important for culture media to always be kept shaking whilst the cells are growing to constantly provide them with oxygen. Allowing the broth to rest even for short periods of time can result in a lower transformation efficiency. All pipetting should be performed as quickly as possible to reduce the amount of time when the culture media are still.

When making overnight cultures, conical shake flasks should preferably be used. The foam plug in the neck of the flasks allows exchange of air between the interior and exterior of the flask. Capped glass tubes can also be used as the caps are loose fitting and also allow air passage. Screw-cap plastic tubes should never be used as these are airtight. This is important for all overnight bacterial cultures but particularly for B. subtilis as it cannot survive anoxic conditions.

Problems Encountered when Working with B. subtilis

When we began work on B.subtilis we knew very little about the organism and therefore made some basic errors. For one transformation we used screw-cap plastic tubes, which significantly reduced both the number and size of the colonies on agar. Leaving them to grow for a further 6 hours allowed them to grow large enough for colony stabs to be taken.

Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS) for B. subtilis

'Perfect' Bacillus RBS' + atg3, 4:

TAAGGAGGAACTACTATG

Promoters

All promoters below contain an RBS but the promoter sequence is not known for all of these.

Inducible promoters in B. subtilis:

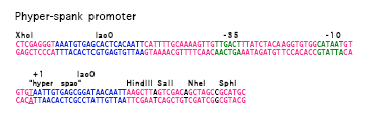

Phyper_spank:

Image from David Rudner, unpublished.

Hy_spank

- IPTG inducible if LacI is present, otherwise very strong constitutive

- range between 0 and 1 mM IPTG5:

GACTCTCTAGCTTGAGGCATCAAATAAAACGAAAGGCTCAGTCGAAAGACTGGGCCTTTC GTTTTATCTGTTGTTTGTCGGTGAACGCTCTCCTGAGTAGGACAAATCCGCCGCTCTAGC TAAGCAGAAGGCCATCCTGACGGATGGCCTTTTTGCGTTTCTACAAACTCTTGTTAACTC TAGAGCTGCCTGCCGCGTTTCGGTGATGAAGATCTTCCCGATGATTAATTAATTCAGAAC GCTCGGTTGCCGCCGGGCGTTTTTTATGCAGCAATGGCAAGAACGTTGCTCGAGGGTAAA TGTGAGCACTCACAATTCATTTTGCAAAAGTTGTTGACTTTATCTACAAGGTGTGGCATA ATGTGTGTAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTAAGGAGGAACTACTATG

Pxyl

- xylose inducible

- range between 0 and 2 % xylose

- depends on relief from XylR repressor6:

TCGGATCTTCATGAAAAACTAAAAAAAATATTGAAAATACTGATGAGGTTATTTAAGATT AAAATAAGTTAGTTTGTTTGGGCAACAAACTAATGTGCAACTTACTTACAATATGACATA AAATGCATCTAGAAAGGAGATTCCTAGGATGGGTACTAAGGAGGAACTACTATG

PspaS

- subtilin inducible

- range between 0 and 10%

- supernatant of a subtilin producing strain

- requires the SpaRK 2-component system7:

GATCTTAAAAAAAGGAAAAAATTGATAAAATCTTGATATTTGTCTGTTACTATTTAGGTA TTGAAAGGAGGTGACCACCATG

Constitutive promoters in B. subtilis:

Low level: PzapA:

CAGCAGGCTGTACGGAATGGTTTTAATCAGGTTTCGGGCAATCTCGATGATTTGCGGATC TTTTAAATCTTTAGAATCCTTAACACCGAGTTCCTTCATTAAAGGAAGCATGGTTTTGTC GACGTACGCGCATACAACCGTCATTGGGCCAAAGTAATCTCCGGTTCCGACTTCGTCAGA ACCGATAACAGACATTCCGGCGATATCTGCCGGAGGGGCATAGCGGGGATCAGCCGGCTT TTTGGCCGTTTTCTTCTTTTCCTGAGGCTCTGCTGTTCCCCAGCGCGCGGATTCTGCCGC AGCGTTTTTTCCTTGAAACAAGACCTTACCTGATTGATATGCTGTAATGGTACAGCCGGG CGGTTTTGCCTGAAAAACGGCTCCCTGCGGAACAGAGGCTGTAAGTGAACCGCTGTACGT CATTTTCATTTGGTCAATAGCAGACAACGATACTTTTATCACTGAATGGGACACGTAATA ATCTCCTTTTTTTACACTTTTCGCTGTATATACCAGTGTATCATAACAGCGGGAGGCTCG TCTTTCCATTCATTTAATAAACGTGTTATGATAAGAACTAGGATTCTCGCGGTAAGGAGG AACTACTATG

Medium level: PftsW:

CTGCGAAAAGCGGCGTATCCGGCGGGATAATGGGCATTTCGCCTTACGATTTCGGGATCG GCATATTCGGCCCCGCATTAGACGAAAAAGGGAACAGCATTGCAGGTGTAAAGCTTTTGG AAATAATGTCTGAGATGTACAGGCTGAGTATTTTTTAATTTATGTCATATGCTTAAATCC TCTTGCATTTTCTGTTGATACCCTTTATGATAAATAGAAGAATTAGGTACTCGCCTGGGG AACGGAGGGATACTTTTGGCTTCAGAGATGATAGTTGACCATCGGCAAAAAGCTTTTGAA CTCTTAAAAGTGGACGCTGAGAAGATTTTGAAGCTGATCCGAGTACAAATGGATAACTTA ACGATGCCTCAATGTCCTCTATATGAAGAGGTTTTAGATACTCAAATGTTCGGGCTTTCG AGGGAAATCGATTTTGCTGTCCGCCTGGGATTGGTTGATGAAAAAGACGGTAAAGACCTT TTATACACATTGGAGCGCGAATTGTCTGCTTTGCATGACGCGTTTACAGCTAAATAAATG ATAAAACTCAAACTTATTAACAGTTTGGGTTTTTTTATAACCGCTATTTTTCTCTCATCT CATAAAAGACGGTCTTTTTTTACACATTCCTTCCGAATCGTATAGAGATTCTTCGTCTCG TTTGATAAATTGTAGTAAAATAAAAAAGATAAATACATAAAAACCATAGATAATGGAAGT TAGAAGCTAAGGAGGAACTACTATG

High level: Pveg

GCGTACAGACATTCTAAGCACTTTGTTGAAACAGTTCAAACAGCCCGAAAAAAGATCCCT CACTTAGATCAGCTTGTTATTTTTGCGGGGGCCTGCCAATCCCATTTTGAATCACTCATC AGAGCGGGTGCGAATTTTGCAAGTTCACCGTCAAGAGTCAATATTCATGCGCTTGATCCG GTATATATCGTCGCGAAGATCAGCTTTACGCCGTTTATGGAACGGATTAATGTATGGGAA GTGCTCCGTAATACGCTGACAAGAGAGAAAGGGCTTGGAGGTATTGAAACAAGAGGAGTT CTGAGAATTGGTATGCCTTATAAGTCCAATTAACAGTTGAAAACCTGCATAGGAGAGCTA TGCGGGTTTTTTATTTTACATAATGATACATAATTTACCGAAACTTGCGGAACATAATTG AGGAATCATAGAATTTTGTCAAAATAATTTTATTGACAACGTCTTATTAACGTTGATATA ATTTAAATTTTATTTGACAAAAATGGGCTCGTGTTGTACAATAAATGTTAAGAGGAGGAA CTACTATG

Bacillus Terminators

rrnO:

TAGGACGCCGCCAAGCCAGCTTAAACCCAGCTCAATGAGCTGGGTTTTTTGTTTGTTAAA AATGAAGAAGAAACTGTGAAGCGTATTTA

rrnA:

TAAAATCTAAGACATATCATGATTTATAAAAACAAAAAAACCTTGCAGGATATGCAAGGC TTCTGGATGACCCGTACGGGATTCGAAC

The Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology

Newcastle is lucky enough to have The Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology (CBCB), part of the Institute for Cell and Molecular Biosciences (ICaMB) at Newcastle University, on its doorstep. CBCB host the largest group of scientists in Europe working on the physiology and molecular biology of Bacillus. As a result, we can make use of the expertise of the researchers based at the centre, which includes some of our advisors

Acknowledgements

The Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology

The Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/ The Institute for Cell and Molecular Biosciences at Newcastle University]

[http://www.cs.ncl.ac.uk/ Newcastle University School of Computing Science]

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/staff/profile/colin.harwood Colin Harwood]

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/staff/profile/l.hamoen Leendert Hamoen]

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/staff/profile/j.w.veening Jan-Willem Veening]

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/staff/profile/jeff.errington Jeff Errington]

[http://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/j.s.hallinan/ Jennifer Hallinan]

[http://www.ncl.ac.uk/camb/staff/profile/anil.wipat Anil Wipat]

[http://www.cs.ncl.ac.uk/people/matthew.pocock Matthew Pocock]

References

- Veening, J.-W., Igoshin, O. A., Eijlander, R. T., Nijland, R., Hamoen, L. W., Kuipers, O. P. (Apr 2008) “Transient Heterogeneity in Extracellular Protease Production by Bacillus subtilis” Molecular Systems Biology 4: 184

- Smits, W. K., Kuipers, O. P., Veening, J.-W. (2006) “Phenotypic Variation in Bacteria: the Role of Feedback Regulation” Nature 4: 259-271

- Vellanoweth and Rabinowitz (Mol Micro., 1992, 6 1105-1114)

- Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, van Oudenaarden A. Nat. Genet 2002 May;31(1):69-73

- Quisel, J., Burkholder, W.F., and Grossman, A.D. J Bacteriol. 2001 183 6573-8.

- Hastrup, S. (1988) Analysis of the Bacillus subtilis xylose region. In Genetics and Biotechnology of Bacilli. Ganesan, A.T., and Hoch, J.A. (eds). New York: Academic Press, pp. 79–83

- Bongers et al, 2005 Applied and Environmental Microbiology

"

"