Team:ETH Zurich/Project/Motivation

From 2008.igem.org

(→Current approaches) |

(→Goal – self-optimizing E. coli) |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | + | {|style="background:#FFFFFF ; border:3.5px solid #60AFFE; padding: 1em; margin: auto ; width:98.5% " | |

| - | {|style="background:# | + | |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<!-- PUT THE PAGE CONTENT AFTER THIS LINE. THANKS :) --> | <!-- PUT THE PAGE CONTENT AFTER THIS LINE. THANKS :) --> | ||

| - | + | __TOC__ | |

== Why in this case simpler is better ... == | == Why in this case simpler is better ... == | ||

| - | Building new functions into cells is the goal of synthetic biology. To achieve this, circuits encoding | + | Building new functions into cells is the goal of synthetic biology. To achieve this, circuits encoding the desired behavior have to be inserted into an existing network of already considerable complexity where many of the interactions are not completely understood. By reducing the complexity of the target organism, these interdependencies can be reduced and more predictable results can be obtained. |

| + | |||

| + | One of the main engineering goals in this field is to make the design of new circuits more deterministic, allowing for predictive mathematical models and for simulations of new functions before these are implemented in vivo. Cross-talk between the different pathways in the organism and the additionally implemented circuits can lead to interferences, making the behavior difficult to predict. In such cases "debugging" of the inserted circuit can be circuit can be extremely cumbersome. A minimal cell would arguably provide a more predictable chassis when used as an engineering fundament. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Engineering chassis == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our main motivation is to develop a method to reduce the complexity of the target organism dramatically. This will allow to characterize the biochemical reactions that are necessary to sustain life, eliminating all the "ballast" that may interfere with the inserted functions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The result of this work work would be a "cell factory" with more predictable and controllable behavior, allowing for a more deterministic approach to metabolic engineering. Many groups have been working on this field [1]. Using organisms as varied as obligate parasites like Mycoplasma genitalium (580 kbp), Escherichia coli (4.6 Mbp) to Sacharomices cerevisiae (6Mbp). In all cases, the goal is to obtain a laboratory strain that can be used as a platform in synthetic biology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the genomic sequence of E. coli has been determined (2, 3) and single-knockout libraries exist (4), we still are just beginning to understand E. coli as a whole system. Therefore, it is very difficult to decide based on genetic and biochemical information which genes should be deleted. In addition, it can be expected that disrupted biosynthetic pathways reroute and form novel pathways that can not be predicted based on the data available to date. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By reducing the complexity of the organism, we are trying to move from a network with a large number of (unknown) interactions like this: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:network1.png|center|frame|Fig 1: Metabolic network of e.coli (Nature Reviews)]] | ||

| + | |||

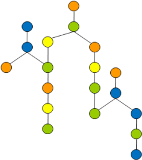

| + | to a well characterized system, in which a complete characterization of possible interactions can be obtained. The result of this effort should provide us with something more in line with this: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:network2.png|center|frame|Fig 2: Schematic representation of a simpler metabolic network]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In this way we are trying to get rid of "annoying" effects like redundancy, unused genes, complex regulation and cross-talk. Our engineering chassis should provide a basis with known functions and a nice platform for the implementation of orthogonal circuits. Recently, a cleaned-up version of E. coli containing a 15% smaller genome in which cryptic sequences, biosynthetic pathways that are not needed under standard culture conditions and other genes had been deleted by targeted large- scale gene disruption has been presented (5). Despite having fewer genes than the standard E. coli, the cells with reduced genome grew slightly denser in certain media, tolerated a greater variety of plasmids and had higher electroporation efficiency. These results can be seen as evidence, that reducing the complexity of the network will provide a neutral environment, where biochemical reactions can take place in a more predictable way. | ||

| - | + | == Goal – self-optimizing E. coli== | |

| - | + | We postulate that random disruption of genes combined with an evolutionary approach in which growth speed determines fitness and survival would be a viable approach to obtain a cell that is perfectly adapted to laboratory growth conditions and has jettisoned all genes that are not contributing towards growth and reproduction under the specified growth conditions. Furthermore, the cell could be adapted rapidly to different conditions and – with appropriate experimental design - it could be rapidly optimized for recombinant expression of proteins. | |

| - | + | In order to prove the viability of the concept, we intend to demonstrate that .. | |

| - | + | a) .. excision of genomic sequences by restriction enzymes can be performed within the living cell; | |

| - | + | b) .. fragmented genomic DNA can be ligated inside the living cell by simultaneous expression of T4 ligase; | |

| - | + | c) .. pulse generators that produce pulses of protein expression of variable length terminated by induction with a second compound can be devised both on the transcriptional as well as on the translational level; | |

| - | + | d) .. cells with optimized growth and reproduction can be selected by competition inside chemostat cultures. | |

| - | + | Please visit the [[Team:ETH Zurich/Project/Background|background]] and the [[Team:ETH Zurich/Project/Approach|approach]] sections for more details. | |

| - | + | == References == | |

| - | + | (1) Mizoguchi, H. et al. (2007) Minireview Escherichia coli minimum genome factory. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46 | |

| - | + | (2) Blattner, F. R. et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277, 1453-74. | |

| + | (3) Riley, M. et al. (2006) Escherichia coli K-12: a cooperatively developed annotation snapshot--2005. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 1-9. | ||

| + | (4) Baba, T.et al. (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2, 2006 0008. | ||

| + | (5) Posfai, G.et al. (2006) Emergent properties of reduced-genome Escherichia coli. Science 312, 1044-6. | ||

Latest revision as of 09:57, 30 October 2008

Why in this case simpler is better ...Building new functions into cells is the goal of synthetic biology. To achieve this, circuits encoding the desired behavior have to be inserted into an existing network of already considerable complexity where many of the interactions are not completely understood. By reducing the complexity of the target organism, these interdependencies can be reduced and more predictable results can be obtained. One of the main engineering goals in this field is to make the design of new circuits more deterministic, allowing for predictive mathematical models and for simulations of new functions before these are implemented in vivo. Cross-talk between the different pathways in the organism and the additionally implemented circuits can lead to interferences, making the behavior difficult to predict. In such cases "debugging" of the inserted circuit can be circuit can be extremely cumbersome. A minimal cell would arguably provide a more predictable chassis when used as an engineering fundament. Engineering chassisOur main motivation is to develop a method to reduce the complexity of the target organism dramatically. This will allow to characterize the biochemical reactions that are necessary to sustain life, eliminating all the "ballast" that may interfere with the inserted functions. The result of this work work would be a "cell factory" with more predictable and controllable behavior, allowing for a more deterministic approach to metabolic engineering. Many groups have been working on this field [1]. Using organisms as varied as obligate parasites like Mycoplasma genitalium (580 kbp), Escherichia coli (4.6 Mbp) to Sacharomices cerevisiae (6Mbp). In all cases, the goal is to obtain a laboratory strain that can be used as a platform in synthetic biology. While the genomic sequence of E. coli has been determined (2, 3) and single-knockout libraries exist (4), we still are just beginning to understand E. coli as a whole system. Therefore, it is very difficult to decide based on genetic and biochemical information which genes should be deleted. In addition, it can be expected that disrupted biosynthetic pathways reroute and form novel pathways that can not be predicted based on the data available to date. By reducing the complexity of the organism, we are trying to move from a network with a large number of (unknown) interactions like this: to a well characterized system, in which a complete characterization of possible interactions can be obtained. The result of this effort should provide us with something more in line with this:

Goal – self-optimizing E. coliWe postulate that random disruption of genes combined with an evolutionary approach in which growth speed determines fitness and survival would be a viable approach to obtain a cell that is perfectly adapted to laboratory growth conditions and has jettisoned all genes that are not contributing towards growth and reproduction under the specified growth conditions. Furthermore, the cell could be adapted rapidly to different conditions and – with appropriate experimental design - it could be rapidly optimized for recombinant expression of proteins. In order to prove the viability of the concept, we intend to demonstrate that .. a) .. excision of genomic sequences by restriction enzymes can be performed within the living cell; b) .. fragmented genomic DNA can be ligated inside the living cell by simultaneous expression of T4 ligase; c) .. pulse generators that produce pulses of protein expression of variable length terminated by induction with a second compound can be devised both on the transcriptional as well as on the translational level; d) .. cells with optimized growth and reproduction can be selected by competition inside chemostat cultures. Please visit the background and the approach sections for more details. References(1) Mizoguchi, H. et al. (2007) Minireview Escherichia coli minimum genome factory. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46 (2) Blattner, F. R. et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277, 1453-74. (3) Riley, M. et al. (2006) Escherichia coli K-12: a cooperatively developed annotation snapshot--2005. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 1-9. (4) Baba, T.et al. (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2, 2006 0008. (5) Posfai, G.et al. (2006) Emergent properties of reduced-genome Escherichia coli. Science 312, 1044-6.

|

"

"