Team:Heidelberg/Human Practice/Open Day

From 2008.igem.org

(New page: __NOTOC__ <html> <link rel='stylesheet' href='http://igem-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/Wiki/Heidelberg2.css' type='text/css' /> <link rel="stylesheet" href="http://igem-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/...) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | + | _NOTOC__ | |

<html> | <html> | ||

<link rel='stylesheet' href='http://igem-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/Wiki/Heidelberg2.css' type='text/css' /> | <link rel='stylesheet' href='http://igem-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/Wiki/Heidelberg2.css' type='text/css' /> | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

| - | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/ | + | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Chemotaxis" style="color: white">Modeling<!--[if gt IE 6]><!--></a><!--<![endif]--> |

<!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | <!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | ||

<ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM3"> | <ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM3"> | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

| - | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Notebook/ | + | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Notebook/Sensing_Group/Notebook" style="color: white">Notebook<!--[if gt IE 6]><!--></a><!--<![endif]--> |

<!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | <!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | ||

<ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM5"> | <ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM5"> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li style="width: 160px"> | <li style="width: 160px"> | ||

| - | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/ | + | <a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/General_information" style="color: white">Human Practice<!--[if gt IE 6]><!--></a><!--<![endif]--> |

<!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | <!--[if lt IE 7]><table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tr><td><![endif]--> | ||

<ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM4"> | <ul class="DropDownMenu" id="MB1-DDM4"> | ||

| - | + | <li><a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/General_information"><span><span>Phips the Phage</span></span></a></li> | |

| - | + | <li><a href="https://2008.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/Science_Communication"><span><span>Scientific Communication</span></span></a></li> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

<!--[if lte IE 6]></td></tr></table></a><![endif]--> | <!--[if lte IE 6]></td></tr></table></a><![endif]--> | ||

| Line 122: | Line 117: | ||

</body> | </body> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Open Day''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the 27th of October, we will carry out an Open Day for school classes. We will present Synthetic Biology, iGEM and our project. We also let the pupils experience to do lab work on their own and therefore set up a little parcours to visualize, isolate and proof the existence of Biobricks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ... we will soon report on it in detail | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Material to carry out an Open Day on Synthetic Biology''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | We provide the idea and the material needed to carry out an open day for a school class, presenting synthetic biology (and optionally iGEM). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Number of visitors: 20 pupils | ||

| + | |||

| + | Time needed: 5 hours | ||

| + | |||

| + | Schedule: | ||

| + | • Introduction and Presentation on iGEM, Synthetic Biology and your project | ||

| + | • Explaining the idea of BioBricks and the labwork in greater detail | ||

| + | • Lab parcour including the stations: Microscopy, Miniprep, Gel electrophoresis | ||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Minipreparation''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | After being given a theoritcal introduction, the pupils carry out a plasmid minipreparation using a standard kit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Theoritcal background:''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | All synthetic biologists in the lab need plasmids as very important tools for their work. You can find them in bacterial cells – either naturally, or put in there by scientists. The bacteria amplify the plasmids in their cells (they replicate them, meaning they make identical copies) and of course they multiply the total amount of plasmids by growing – more bacteria means more plasmids on the whole. If we want to work with these plasmids, like checking whether they are the right ones or engineering them, we need to get them out of the bacteria. Therefore we need plasmid preparation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The procedure is simple, but honestly, it is not very convenient for the bacteria: We need to destroy them; scientists say to lyse them, to set the plasmids free together with the other contents of the cell. Then you will have a mixture of DNA (chromosome and plasmids), RNA, proteins and others cell components. But you only need the plasmid DNA in this case, everything else has to be separated from it, because the rest can have a negative effect on further applications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The method we mostly use in the laboratory to isolate plasmids is called alkaline lysis. This classical method is today standardized. Like the name implicates, you need alkaline agents for the lysis of the cell. Additionally, you use detergents, to break the cell wall and lyse the cells. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Miniprep_eng.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''1. Lysis''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can, for example, also find detergents in washing agents. There they help to remove grease spots. This works as follows: Detergents have a very similar structure to lipids. They therefore can mix with them and loose their connection to fibres of the clothes. In Bacteria, they act in a very similar way: They mix with the lipids that form the bilayer of the plasma membrane and destroy there ordered structure. This is how they make holes in the plasma membrane, which leads to the lysis of the cell. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2. Precipitation and separation of proteins and chromosomal DNA''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we come to the alkaline part of this procedure: In adding sodium hydroxide (NaOH) to the solution, the pH is increased from roughly 7 to 12. Because this is a huge contrast to the normal physiological pH, proteins and DNA denature and change their conformation. RNA is degraded. Proteins and DNA, which are denatured cannot be soluted any more and precipitate. You all know the phenomenon of denatured proteins from making fried eggs: The egg changes its consistency if you heat it and gets hard – this is due to the denaturising proteins. The same effect as heat, have acids or bases (like NaOH). In denatured DNA, the two strands get separated from each other. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The trick the alkaline method uses, to separate the plasmid DNA from the chromosomal DNA and the proteins, is to lower the pH again by adding acid (for example potassium acetate) to the solution. If the pH approximates the physiological one, the plasmids are able to renature first, because they are small and the two DNA strands find each other with a much higher possibility than the ones of the big chromosome. Therefore if you keep the renaturising step short, only the plasmids are able to build double helices and solute again. The chromosomal DNA and the proteins stay precipitated. They can be separated from the plasmids by centrifugation. | ||

| + | (The white solids on the tube after centrifugation are the precipitated proteins, DNA and other cell components. The plasmid DNA is soluted in the clear supernatant.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''3. Binding of DNA''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now how do we get the plasmids out of this salty solution (remember we put a lot of salts to the solution to first rise, then lower the pH) into a clear one that can be used for further applications? You could precipitate the plasmids like we did with the proteins before, but there is another possibility, which is widely used today: | ||

| + | You bind the DNA to a solid phase. This often consists of silica, which can be used in a bead like form, but in most cases, it is included in a column integrated in an eppendorf tube. The DNA can bind to the silica column, if the solution is very salty. If you centrifuge, the salty solution is drawn through the column into the tip of the tube and the DNA remains bound to the column. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''4. Eluation of the plasmids''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the last step, you eluate the DNA from the column, meaning you loosen the bonds between DNA and silica and solute the DNA again. This is possible with every solution containing low or no salt at all. You can take water, for example. You put it on the column, centrifuge again, but this time the DNA will also be drawn through the column into the tip of the tube together with the water. | ||

| + | You can then proceed to work with your purified plasmids: you can, for example, check, whether you have isolated the right one using agarose gel electrophoresis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Minipräparation (German)''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Eines der wichtigsten Arbeitsutensilien des Wissenschaftlers der Synthetischen Biologie sind Plasmide. Diese befinden sich in Bakterienzellen, beziehungsweise werden von Wissenschaftlern dort eingeschleust. Die Bakterien vermehren diese Plasmide in ihren Zellen; sie replizieren sie (fertigen identische Kopien an). Natürlich erhöhen sie die Gesamtanzahl an Plasmiden auch dadurch, dass sie sich teilen: mehr Bakterien produzieren entsprechend mehr Plasmide. Wenn wir nun mit diesen Plasmiden weiterarbeiten wollen, wenn wir sie zum Beispiel verändern möchten, oder auch nur schauen, ob die Bakterien tatsächlich die richtigen Plasmide besitzen, dann müssen wir die Plasmide wieder aus den Bakterien herausbekommen. Das machen wir mir Hilfe einer Plasmidpräparation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Das Verfahren ist einfach, wenn auch nicht angenehm für die Bakterien: Um die Plasmide zu isolieren, werden die Bakterien schlichtweg zerstört, man sagt auch: sie werden lysiert. Dabei wird der Inhalt der Bakterien freigesetzt und mit ihm auch die Plasmid-DNA. Diese muss in den folgenden Schritten gereinigt werden, sprich von den Resten der Bakterien befreit und von noch vorhandenen Proteinen getrennt werden, denn diese würden die folgenden Arbeitsschritte stören. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Miniprep.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Die Methode, die wir hierzu im Labor verwenden, und für die es auch standardisierte Verfahren zur Durchführung gibt (Kits und Automaten) ist die der alkalischen Lyse. Sie ist eine der klassischen Methoden zur Plasmidpräparation. | ||

| + | Wie es der Name schon sagt, werden hierzu alkalische Substanzen verwendet, zusammen mit einem Detergenz (zum Beispiel Sodium Dodecylsulfat – SDS), um die Zellwand der Bakterien aufzubrechen, und diese so zu lysieren. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''1. Lyse''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Detergenzien findet man auch in Waschmitteln. Dort helfen sie, Fettflecken zu lösen, indem sie sich mit den Lipiden mischen und sie von den Fasern der Kleidungsstücke ablösen. Wenn man Detergenzien zu Bakterienzellen gibt, mischen sich sich unter die Lipide, die die Biomembranen des Bakteriums aufbauen und zerstören deren Ordnung. So entstehen Löcher in der Plasmamembran der Bakterien und sie lysieren. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2. Fällung und Abtrennen von Proteinen und chromosomaler DNA''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nun kommen wir zu dem Schritt, der der ganzen Methode den Namen gibt: Durch Zugabe von Natriumhydroxid (NaOH), einer Lauge, wird der pH der Lösung bis auf 12 erhöht. Da dieser sich sehr stark vom normalen pH in Zellen unterscheidet (pH 7,4), denaturieren unter diesen Bedingungen DNA und Proteine. RNA wird abgebaut (auch von extra hinzugegebenen Enzymen). Die denaturierte DNA und Proteinmoleküle sind in der Lösung nicht mehr stabil und fallen aus. Das Phänomen denaturierender Proteine kennt wohl jeder von Spiegeleiern: Erhitzt man die Eier verändert sich ihre Konsistenz und sie werden hart, weil durch die Hitze die Proteine denaturieren. Einen ähnlichen Effekt auf Proteine haben Säuren und Laugen. Beim Denaturieren von DNA trennen sich die beiden Stränge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Der Trick der alkalische Lyse ist nun, die Plasmid-DNA von der restlichen DNA und den Proteinen zu trennen, indem durch Zugabe von Säure die Lösung wieder neutral(er) gemacht wird. Die kleine Plasmid-DNA kann als erstes wieder renaturieren und in Lösung gehen, wenn der pH-Wert sinkt, indem die beiden Partnerstränge sich finden und wieder eine Doppelhelix ausbilden. Dies geschieht wesentlich leichter und schneller als bei den großen chromosomalen DNA-Strängen. Lässt man die DNA also nur kurz bei neutralem pH, renaturiert nur die Plasmid-DNA und kann dadurch wieder gelöst werden. | ||

| + | Die Proteine, genauso wie die DNA des Bakterienchromosoms können nicht wieder in Lösung gehen. Sie können von den Plasmiden getrennt werden, indem man das Ganze zentrifugiert. Die weißen Überbleibsel am Eppi sind die denaturierten Bestandteile der Lösung, im klaren Überstand sind die Plasmide gelöst. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''3. Binden von DNA an eine Säule''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nun hätte man die Plasmide isoliert in Lösung vorliegen. Ein Problem ist aber, dass die Lösung sehr hohe Konzentrationen an Salz hat, welches zur pH-Veränderung zugegeben wurde. Hohe Salzkonzentrationen stören aber viele Folgeanwendungen der Plasmide, wie Restriktionsverdaue oder Sequenzierungen. Daher muss die DNA aus der salzigen Lösung in eine weniger salzige überführt werden. | ||

| + | Eine Möglichkeit, das zu erreichen, wäre die Plasmide, ähnlich wie die Proteine zuvor, auszufällen und in Wasser neu zu lösen. Wir verwenden in der Regel jedoch eine andere Technik: | ||

| + | Wir binden die Plasmide an ein festes Trägermaterial, und trennen sie so von ihrem Lösungsmittel. Der Träger ist häufig Silikat. Es wird in Form von Säulen verwendet, die sich in einem Eppendorf-Tube befinden. Daran kann die DNA binden, solange sehr viel Salz in der umgebenden Flüssigkeit ist. Das Prinzip dieser Säulentechnik ist es, die DNA an die Säule unter Hochsalzbedingungen zu binden (wir erinnern uns, dass nach der Abtrennung der Proteine sehr viel Salz in der Lösung vorhanden ist). Gibt man also die Lösung aus dem vorherigen Schritt auf die Säule und zentrifugiert, bleibt die DNA an der Säule haften, das Lösungsmittel mit den Salzen und andere Verunreinigungen werden durch die Säule gezogen und können verworfen werden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''4. Eluieren der DNA''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gibt man auf die Säule mit der DNA eine Lösung ohne / mit wenig Salz, zum Beispiel Wasser, und zentrifugiert erneut, löst sich die DNA im Wasser und wird mit diesem durch die Säule gezogen. Man erhält in dem Säulendurchfluss (Eluat) eine Lösung mit der reinen DNA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Von der gereinigten DNA kann man anschließend die Konzentration bestimmen, um zu sehen, wie viel isoliert wurde. Man kann dann mittels Agarose Gelelektrophorese überprüfen, ob auch die gewünschte DNA isoliert wurde, und nicht etwa irgendetwas anderes. | ||

Revision as of 01:04, 26 October 2008

_NOTOC__

Contents |

Open Day

On the 27th of October, we will carry out an Open Day for school classes. We will present Synthetic Biology, iGEM and our project. We also let the pupils experience to do lab work on their own and therefore set up a little parcours to visualize, isolate and proof the existence of Biobricks.

... we will soon report on it in detail

Material to carry out an Open Day on Synthetic Biology

We provide the idea and the material needed to carry out an open day for a school class, presenting synthetic biology (and optionally iGEM).

Number of visitors: 20 pupils

Time needed: 5 hours

Schedule: • Introduction and Presentation on iGEM, Synthetic Biology and your project • Explaining the idea of BioBricks and the labwork in greater detail • Lab parcour including the stations: Microscopy, Miniprep, Gel electrophoresis

Minipreparation

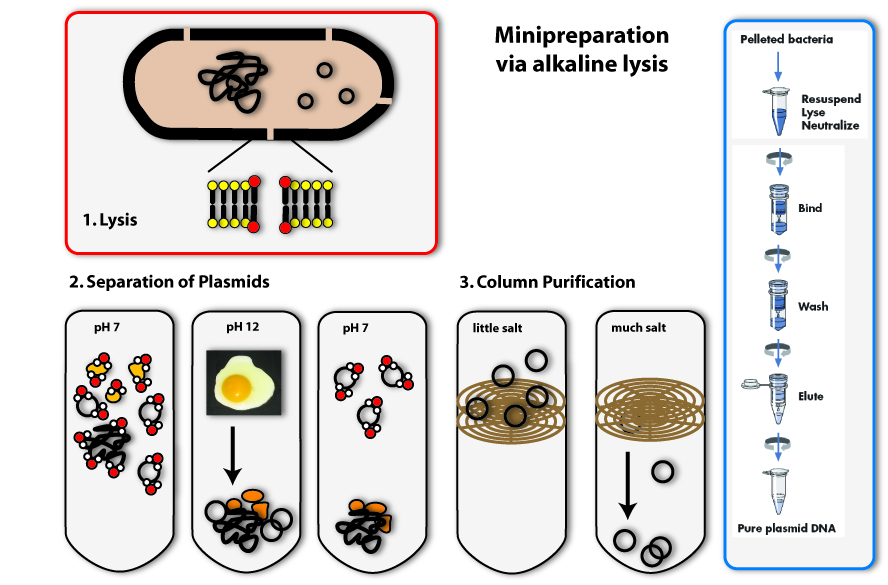

After being given a theoritcal introduction, the pupils carry out a plasmid minipreparation using a standard kit.

Theoritcal background:

All synthetic biologists in the lab need plasmids as very important tools for their work. You can find them in bacterial cells – either naturally, or put in there by scientists. The bacteria amplify the plasmids in their cells (they replicate them, meaning they make identical copies) and of course they multiply the total amount of plasmids by growing – more bacteria means more plasmids on the whole. If we want to work with these plasmids, like checking whether they are the right ones or engineering them, we need to get them out of the bacteria. Therefore we need plasmid preparation.

The procedure is simple, but honestly, it is not very convenient for the bacteria: We need to destroy them; scientists say to lyse them, to set the plasmids free together with the other contents of the cell. Then you will have a mixture of DNA (chromosome and plasmids), RNA, proteins and others cell components. But you only need the plasmid DNA in this case, everything else has to be separated from it, because the rest can have a negative effect on further applications.

The method we mostly use in the laboratory to isolate plasmids is called alkaline lysis. This classical method is today standardized. Like the name implicates, you need alkaline agents for the lysis of the cell. Additionally, you use detergents, to break the cell wall and lyse the cells.

1. Lysis

You can, for example, also find detergents in washing agents. There they help to remove grease spots. This works as follows: Detergents have a very similar structure to lipids. They therefore can mix with them and loose their connection to fibres of the clothes. In Bacteria, they act in a very similar way: They mix with the lipids that form the bilayer of the plasma membrane and destroy there ordered structure. This is how they make holes in the plasma membrane, which leads to the lysis of the cell.

2. Precipitation and separation of proteins and chromosomal DNA

Now we come to the alkaline part of this procedure: In adding sodium hydroxide (NaOH) to the solution, the pH is increased from roughly 7 to 12. Because this is a huge contrast to the normal physiological pH, proteins and DNA denature and change their conformation. RNA is degraded. Proteins and DNA, which are denatured cannot be soluted any more and precipitate. You all know the phenomenon of denatured proteins from making fried eggs: The egg changes its consistency if you heat it and gets hard – this is due to the denaturising proteins. The same effect as heat, have acids or bases (like NaOH). In denatured DNA, the two strands get separated from each other.

The trick the alkaline method uses, to separate the plasmid DNA from the chromosomal DNA and the proteins, is to lower the pH again by adding acid (for example potassium acetate) to the solution. If the pH approximates the physiological one, the plasmids are able to renature first, because they are small and the two DNA strands find each other with a much higher possibility than the ones of the big chromosome. Therefore if you keep the renaturising step short, only the plasmids are able to build double helices and solute again. The chromosomal DNA and the proteins stay precipitated. They can be separated from the plasmids by centrifugation. (The white solids on the tube after centrifugation are the precipitated proteins, DNA and other cell components. The plasmid DNA is soluted in the clear supernatant.)

3. Binding of DNA

Now how do we get the plasmids out of this salty solution (remember we put a lot of salts to the solution to first rise, then lower the pH) into a clear one that can be used for further applications? You could precipitate the plasmids like we did with the proteins before, but there is another possibility, which is widely used today: You bind the DNA to a solid phase. This often consists of silica, which can be used in a bead like form, but in most cases, it is included in a column integrated in an eppendorf tube. The DNA can bind to the silica column, if the solution is very salty. If you centrifuge, the salty solution is drawn through the column into the tip of the tube and the DNA remains bound to the column.

4. Eluation of the plasmids

In the last step, you eluate the DNA from the column, meaning you loosen the bonds between DNA and silica and solute the DNA again. This is possible with every solution containing low or no salt at all. You can take water, for example. You put it on the column, centrifuge again, but this time the DNA will also be drawn through the column into the tip of the tube together with the water. You can then proceed to work with your purified plasmids: you can, for example, check, whether you have isolated the right one using agarose gel electrophoresis.

Minipräparation (German)

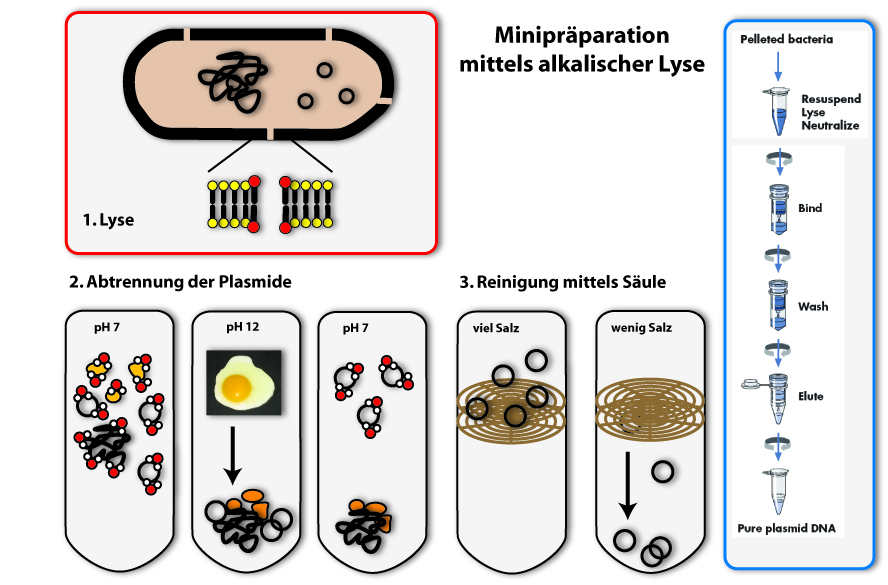

Eines der wichtigsten Arbeitsutensilien des Wissenschaftlers der Synthetischen Biologie sind Plasmide. Diese befinden sich in Bakterienzellen, beziehungsweise werden von Wissenschaftlern dort eingeschleust. Die Bakterien vermehren diese Plasmide in ihren Zellen; sie replizieren sie (fertigen identische Kopien an). Natürlich erhöhen sie die Gesamtanzahl an Plasmiden auch dadurch, dass sie sich teilen: mehr Bakterien produzieren entsprechend mehr Plasmide. Wenn wir nun mit diesen Plasmiden weiterarbeiten wollen, wenn wir sie zum Beispiel verändern möchten, oder auch nur schauen, ob die Bakterien tatsächlich die richtigen Plasmide besitzen, dann müssen wir die Plasmide wieder aus den Bakterien herausbekommen. Das machen wir mir Hilfe einer Plasmidpräparation.

Das Verfahren ist einfach, wenn auch nicht angenehm für die Bakterien: Um die Plasmide zu isolieren, werden die Bakterien schlichtweg zerstört, man sagt auch: sie werden lysiert. Dabei wird der Inhalt der Bakterien freigesetzt und mit ihm auch die Plasmid-DNA. Diese muss in den folgenden Schritten gereinigt werden, sprich von den Resten der Bakterien befreit und von noch vorhandenen Proteinen getrennt werden, denn diese würden die folgenden Arbeitsschritte stören.

Die Methode, die wir hierzu im Labor verwenden, und für die es auch standardisierte Verfahren zur Durchführung gibt (Kits und Automaten) ist die der alkalischen Lyse. Sie ist eine der klassischen Methoden zur Plasmidpräparation. Wie es der Name schon sagt, werden hierzu alkalische Substanzen verwendet, zusammen mit einem Detergenz (zum Beispiel Sodium Dodecylsulfat – SDS), um die Zellwand der Bakterien aufzubrechen, und diese so zu lysieren.

1. Lyse

Detergenzien findet man auch in Waschmitteln. Dort helfen sie, Fettflecken zu lösen, indem sie sich mit den Lipiden mischen und sie von den Fasern der Kleidungsstücke ablösen. Wenn man Detergenzien zu Bakterienzellen gibt, mischen sich sich unter die Lipide, die die Biomembranen des Bakteriums aufbauen und zerstören deren Ordnung. So entstehen Löcher in der Plasmamembran der Bakterien und sie lysieren.

2. Fällung und Abtrennen von Proteinen und chromosomaler DNA

Nun kommen wir zu dem Schritt, der der ganzen Methode den Namen gibt: Durch Zugabe von Natriumhydroxid (NaOH), einer Lauge, wird der pH der Lösung bis auf 12 erhöht. Da dieser sich sehr stark vom normalen pH in Zellen unterscheidet (pH 7,4), denaturieren unter diesen Bedingungen DNA und Proteine. RNA wird abgebaut (auch von extra hinzugegebenen Enzymen). Die denaturierte DNA und Proteinmoleküle sind in der Lösung nicht mehr stabil und fallen aus. Das Phänomen denaturierender Proteine kennt wohl jeder von Spiegeleiern: Erhitzt man die Eier verändert sich ihre Konsistenz und sie werden hart, weil durch die Hitze die Proteine denaturieren. Einen ähnlichen Effekt auf Proteine haben Säuren und Laugen. Beim Denaturieren von DNA trennen sich die beiden Stränge.

Der Trick der alkalische Lyse ist nun, die Plasmid-DNA von der restlichen DNA und den Proteinen zu trennen, indem durch Zugabe von Säure die Lösung wieder neutral(er) gemacht wird. Die kleine Plasmid-DNA kann als erstes wieder renaturieren und in Lösung gehen, wenn der pH-Wert sinkt, indem die beiden Partnerstränge sich finden und wieder eine Doppelhelix ausbilden. Dies geschieht wesentlich leichter und schneller als bei den großen chromosomalen DNA-Strängen. Lässt man die DNA also nur kurz bei neutralem pH, renaturiert nur die Plasmid-DNA und kann dadurch wieder gelöst werden. Die Proteine, genauso wie die DNA des Bakterienchromosoms können nicht wieder in Lösung gehen. Sie können von den Plasmiden getrennt werden, indem man das Ganze zentrifugiert. Die weißen Überbleibsel am Eppi sind die denaturierten Bestandteile der Lösung, im klaren Überstand sind die Plasmide gelöst.

3. Binden von DNA an eine Säule

Nun hätte man die Plasmide isoliert in Lösung vorliegen. Ein Problem ist aber, dass die Lösung sehr hohe Konzentrationen an Salz hat, welches zur pH-Veränderung zugegeben wurde. Hohe Salzkonzentrationen stören aber viele Folgeanwendungen der Plasmide, wie Restriktionsverdaue oder Sequenzierungen. Daher muss die DNA aus der salzigen Lösung in eine weniger salzige überführt werden. Eine Möglichkeit, das zu erreichen, wäre die Plasmide, ähnlich wie die Proteine zuvor, auszufällen und in Wasser neu zu lösen. Wir verwenden in der Regel jedoch eine andere Technik: Wir binden die Plasmide an ein festes Trägermaterial, und trennen sie so von ihrem Lösungsmittel. Der Träger ist häufig Silikat. Es wird in Form von Säulen verwendet, die sich in einem Eppendorf-Tube befinden. Daran kann die DNA binden, solange sehr viel Salz in der umgebenden Flüssigkeit ist. Das Prinzip dieser Säulentechnik ist es, die DNA an die Säule unter Hochsalzbedingungen zu binden (wir erinnern uns, dass nach der Abtrennung der Proteine sehr viel Salz in der Lösung vorhanden ist). Gibt man also die Lösung aus dem vorherigen Schritt auf die Säule und zentrifugiert, bleibt die DNA an der Säule haften, das Lösungsmittel mit den Salzen und andere Verunreinigungen werden durch die Säule gezogen und können verworfen werden.

4. Eluieren der DNA

Gibt man auf die Säule mit der DNA eine Lösung ohne / mit wenig Salz, zum Beispiel Wasser, und zentrifugiert erneut, löst sich die DNA im Wasser und wird mit diesem durch die Säule gezogen. Man erhält in dem Säulendurchfluss (Eluat) eine Lösung mit der reinen DNA.

Von der gereinigten DNA kann man anschließend die Konzentration bestimmen, um zu sehen, wie viel isoliert wurde. Man kann dann mittels Agarose Gelelektrophorese überprüfen, ob auch die gewünschte DNA isoliert wurde, und nicht etwa irgendetwas anderes.

"

"