Team:ETH Zurich/Modeling/Genome Static Analysis

From 2008.igem.org

Restriction Enzyme AnalysisThis section presents the computational investigation we performed in order to understand which restriction enzymes cut the genome in fragments that most probably will lead to find the minimal genome in our reduction approach. It is important to note that this is a "statical" analysis: we do not include in the evaluation of the restriction enzyme optimality any prevision regarding the effects cutting patterns can have on cell physiology or cell system behavior. We address questions regarding the cell system response after genome reduction using more advanced modeling techniques (a genome scale model) in the Genome Scale Analysis section. We focus here only on the insights that can be obtained using three kinds of "statical" information:

Using computational tools and the above mentioned information we are interested in asking (and answering) the following questions:

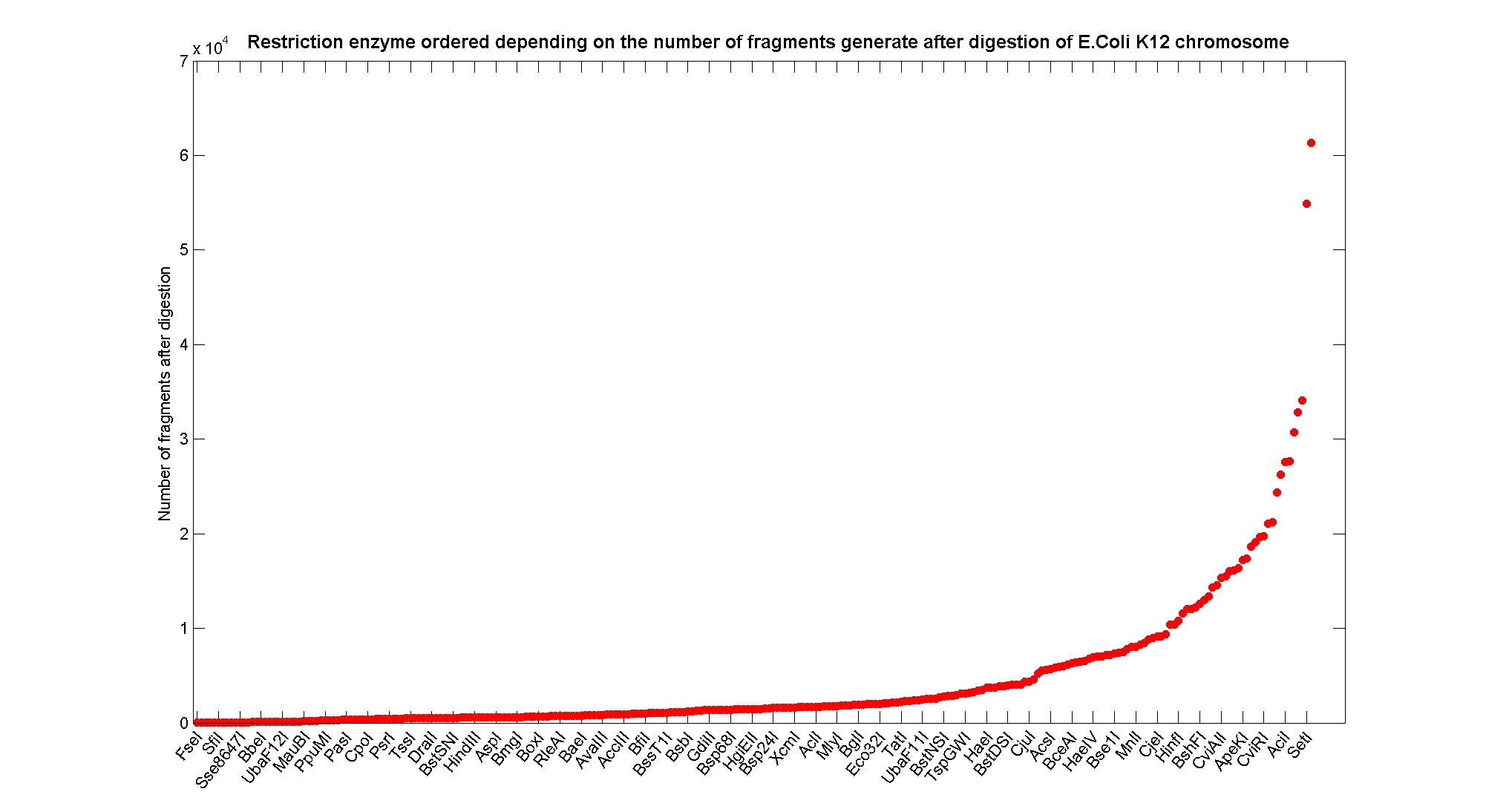

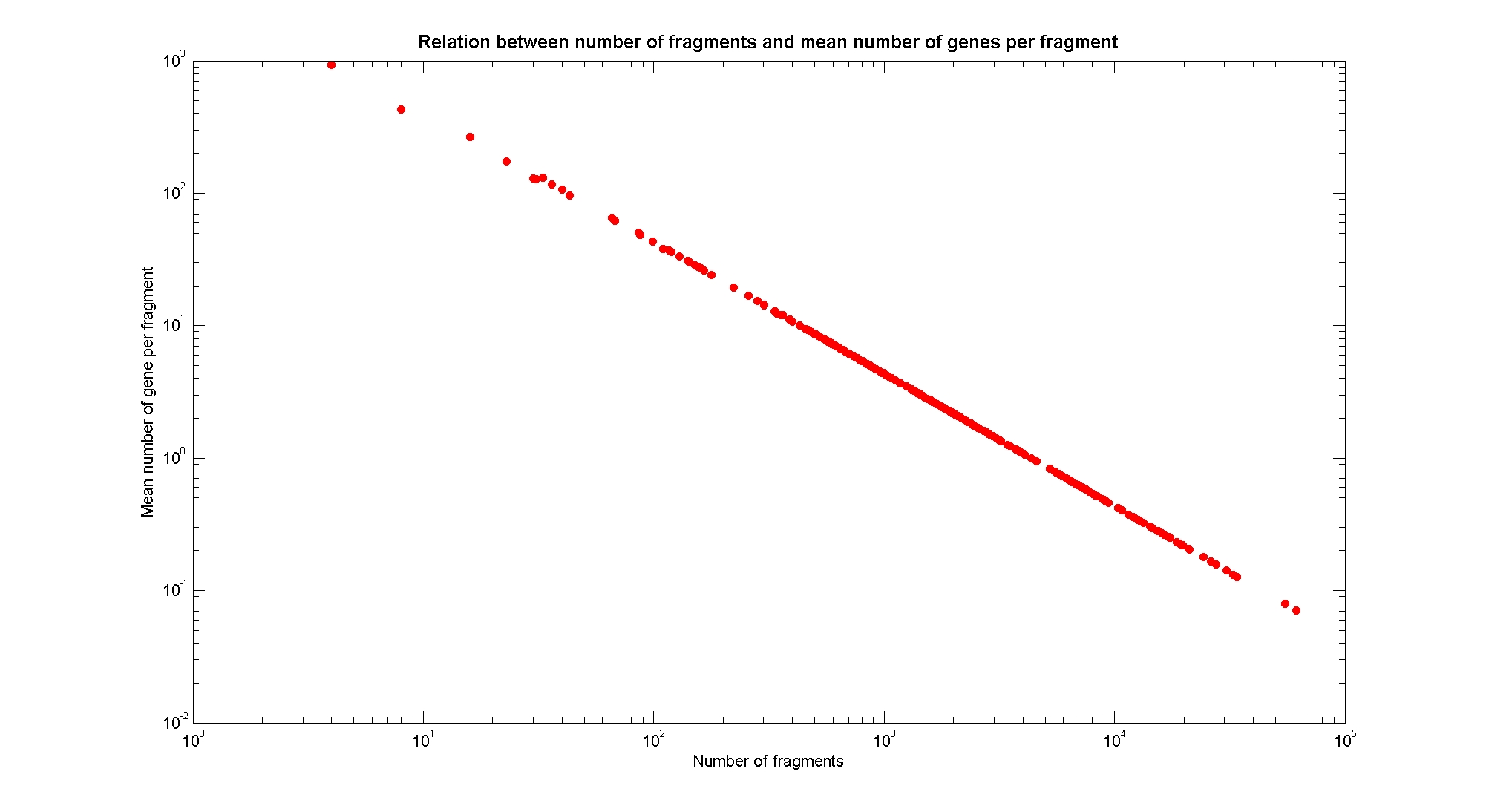

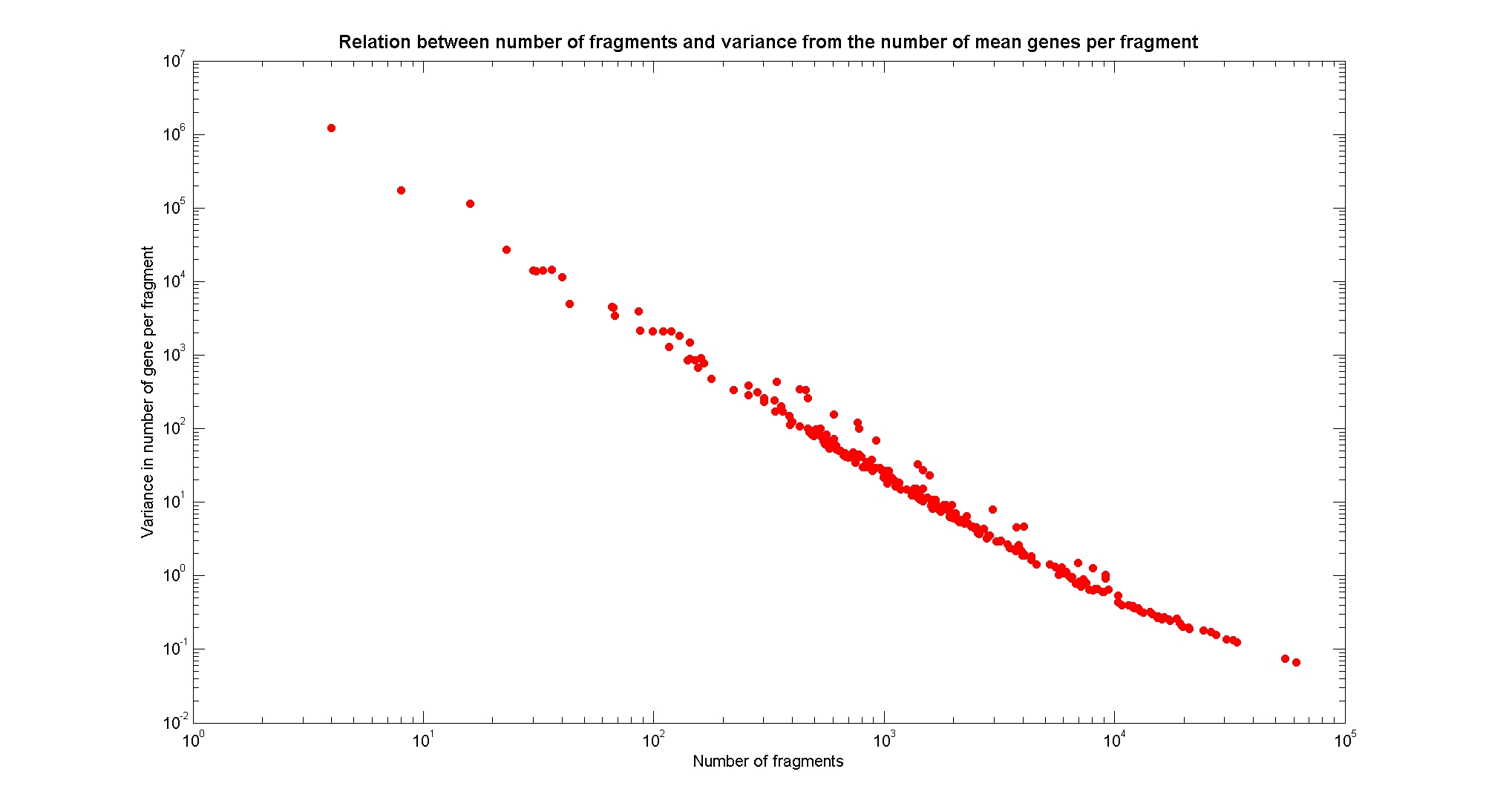

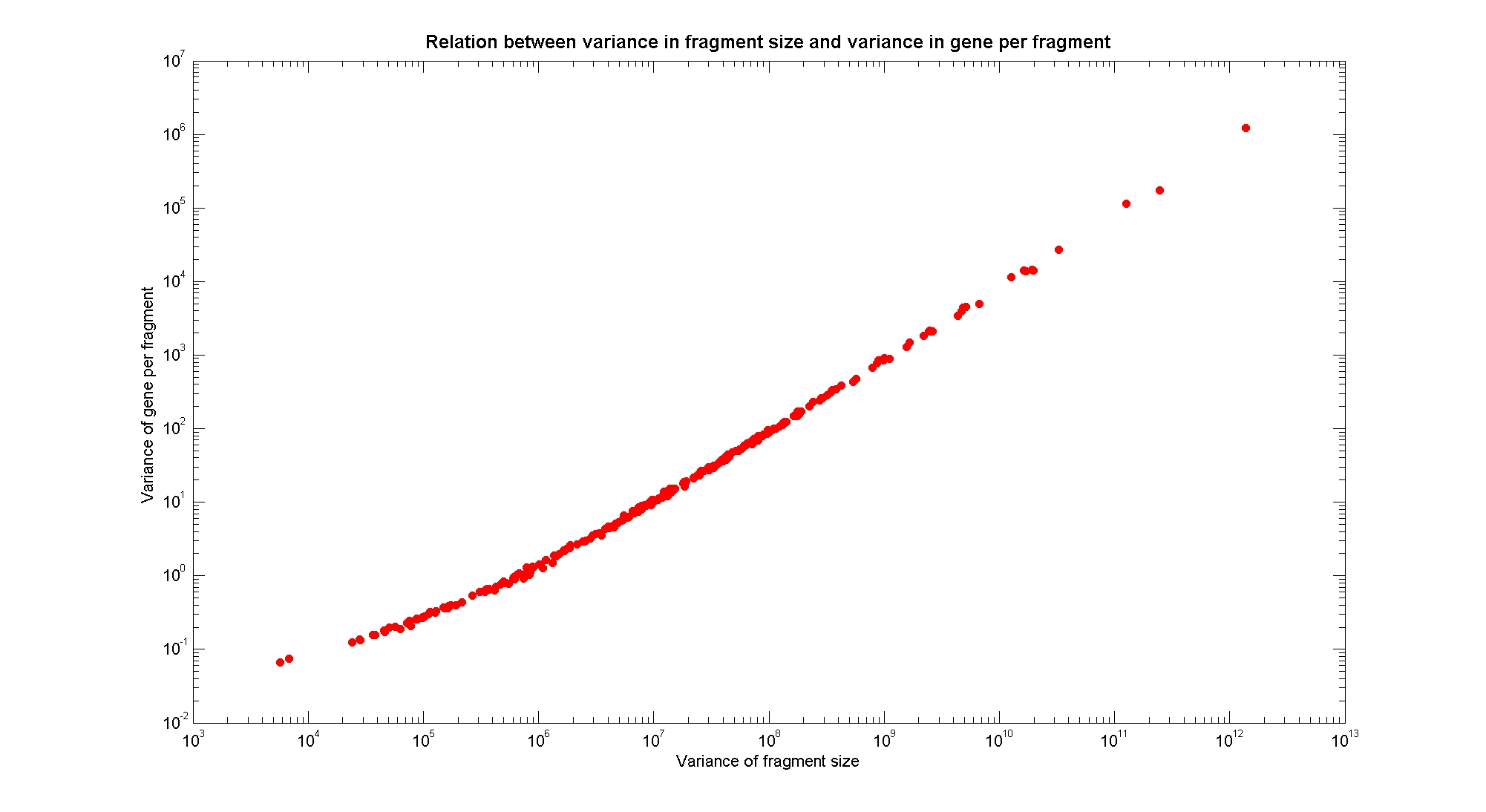

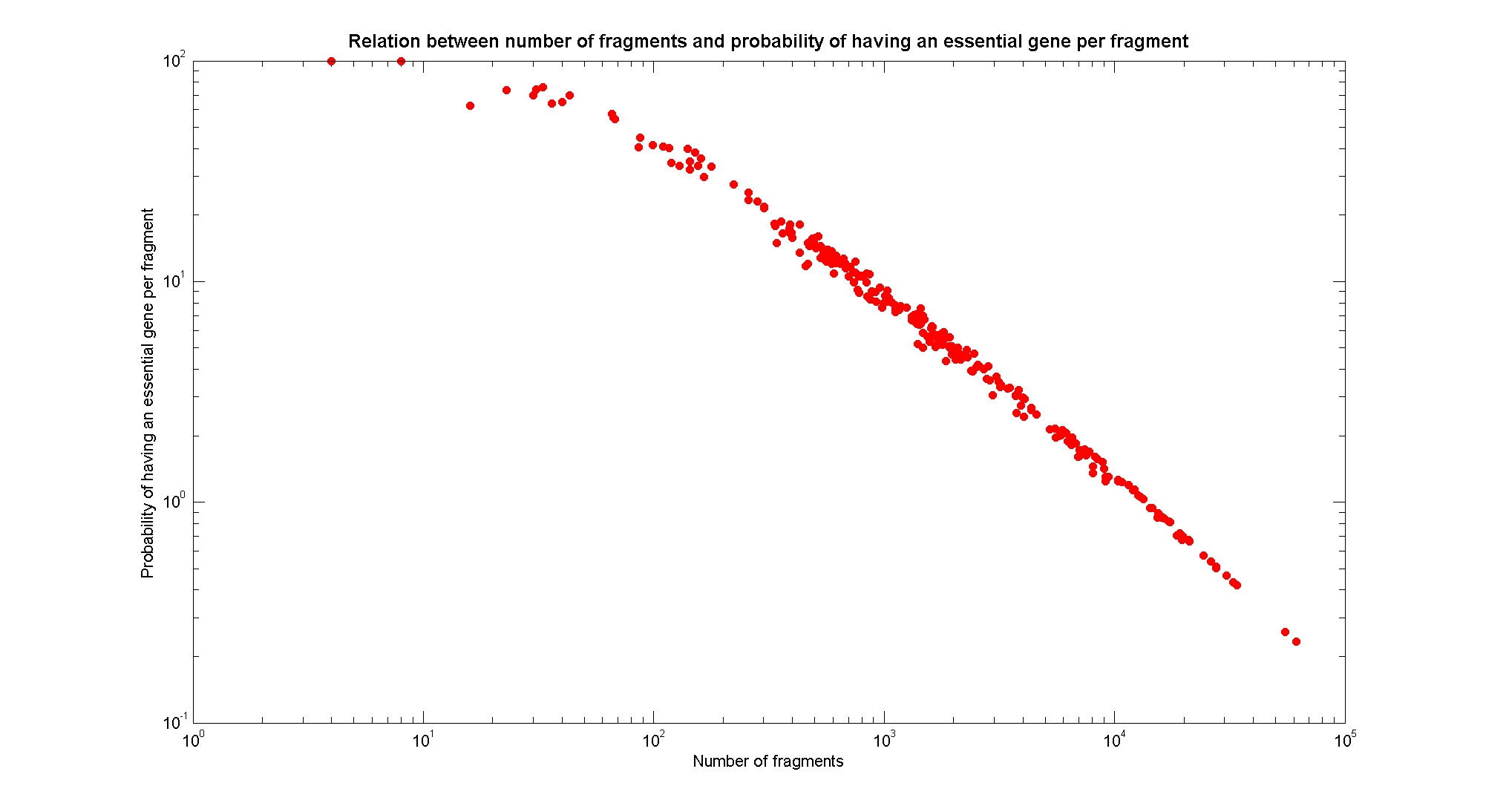

Available restriction enzymes and digestion simulationAs source for the restriction enzyme to consider, we used the [http://rebase.neb.com/rebase/rebase.html REBASE database] (2). We found 713 restriction enzymes that spawn from 4 up to 13 cutters, some with complete specific recognition sites and some with unspecific site properties. Since some of the restriction enzymes present the same recognition site sequence, we grouped them together as a single entity to be tested (216 groups). We downloaded the genome and annotation information regarding E.Coli K12 MG1655 from the GenBank® database. We then simulated the digestion of E.Coli chromosome sequentially for each group of restriction enzymes and performed statistical analysis on the fragment patterns obtained. The following pictures summarize the distribution of the available enzymes regarding their frequency of cutting (number of fragments after digestion): It is possible to note that there is a huge number of restriction enzymes that digest the chromosome in few to high number of fragments (up to 10,000 fragments) and relatively fewer which generate a very high number of fragments. Please note that on the x axis, some of the enzyme groups have been omitted because of space problems and only one of each five has been reported. Analysing the gene content of the fragmentsIn order to understand if there are restriction enzymes that have particular properties (for example the ability to target on the same fragments several essential genes, in order to reduce the probability of causing cell death) we performed some statistical analysis, calculating indexes such as: the mean and variance for fragment lengths, the mean and variance for gene numbers per fragment, the probability of one fragment to contain an essential gene. Here we show the graphs obtained by plotting these indexes.

Result table on chromosomal digestion simulationsUsing our digestion simulation code (that can be downloaded from our download page) we produced a table with the statistic data for each and all the restriction enzyme. The complete table can be consulted here. References(1) "Experimental Determination and System-Level Analysis of Essential Genes in E. coli MG1655", Gerdes et al.,Journal of Bacteriology, 2003 (2) "REBASE: restriction enzymes and methyltransferases", Richard J. Roberts, Tamas Vincze, Janos Posfai, and Dana Macelis, Nucleic Acids Res. 2003 January 1; 31(1): 418–420. |

"

"