Team:BCCS-Bristol/Modeling

From 2008.igem.org

Tgorochowski (Talk | contribs) (→Software) |

(→Bacteria to Particle Adhesion) |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

==Results== | ==Results== | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | [ | + | === Gene Regulatory Network === |

| + | ==== Sender ==== | ||

| + | To assess the sender GRN we were interested in how the strength of the response regulator C<sub>pMax</sub> affects the overall dynamics and the final output of AHL. For a C<sub>pMax</sub> range of [0.1, 100] the qualitative behaviour of the GRN was the same, shown in Figure 1a for a C<sub>pMax</sub> value of 5 molecules per cell. Both GFP and LuxI proteins rise rapidly in the first hour, while CpxR and LuxI mRNA reaches a maximum after 60 minutes. The final LuxI mRNA concentration is low, causing the rate of increase in LuxI protein to slow towards the end of the simulation. In | ||

| + | contrast, both mRNA and protein concentrations of GFP continue to increase rapidly for the duration. | ||

| - | + | Figure 1b shows how the initial C<sub>pMax</sub> value effects AHL output over time. The behaviour is seen to be asymptotic, tending to a final concentration after approximately 400 minutes. The relationship between C<sub>pMax</sub> and AHL appears to be non-linear, with a rapid increase seen between 0.1 and 1. After this point the rate seems to slows, reaching a maximum near 4300. The huge variability in output AHL, even when the initial C<sub>pMax</sub> value is only varied by a small amount, makes it difficult to estimate a realistic output for a single cell. Experimental | |

| - | + | techniques would need to be used to refine the accuracy of these results and allow for an appropriate CpMax value to be chosen. Overall, the GRN exhibits the correct dynamics, giving a sizeable AHL production in the presence of a CpxR response. | |

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-SenderGRNGraph.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 1a: Sender GRN Dynamics''' - Plots showing the mRNA and protein variation when C<sub>pMax</sub> = 5. All states were given initial values of 0]] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-AHL_Variation.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 1b: AHL Output''' - Each line represents a different C<sub>pMax</sub> value.]] | ||

| + | ==== Transport ==== | ||

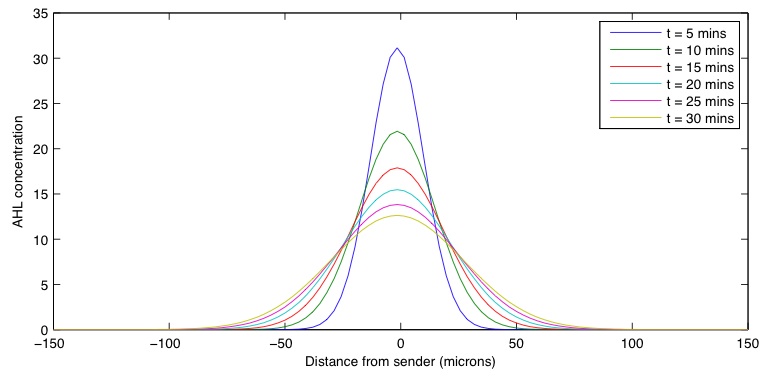

| + | For the transport aspect of the system we investigated how the concentration distribution varied | ||

| + | over time. A delta input of size 50 was used and the concentration distribution calculated over | ||

| + | a 30 minute period. Figure 2 shows the distribution at 5 minute intervals. A value of 0.23 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | was selected for the diffusion co-efficient. | ||

| + | As we do not know the maximal expression level C<sub>pMax</sub> of the response regulator CpxR it | ||

| + | was difficult to estimate the rate that an individual cell would produce AHL. For this reason | ||

| + | we attempted to concentrate on understanding the distance over which a threshold value was | ||

| + | exceeded. The receiver GRN has been shown to be sensitive to low levels of AHL, see previous section, and so we assumed a large response would occur at concentrations of 3 and greater. | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-Transport.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 2: Transport Results''' - Concentration distribution over a 30 min period for an initial delta function input at 0 of 50]] | ||

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | ==== Reciever ==== |

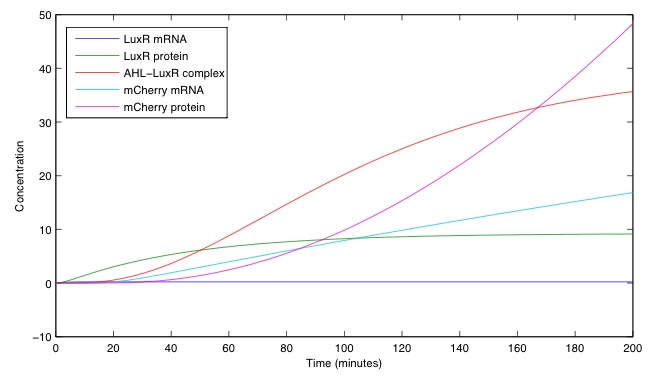

| + | For the receiver we wanted to understand how varying AHL concentration altered output of our | ||

| + | signalling protein mCherry. This relationship is shown in Figure 3b. Availability of any AHL | ||

| + | causes a large increase in mCherry output, however, the rate of increase decays exponentially. | ||

| + | Output increases very little once a concentration of 3 molecules per cell has been reached. | ||

| + | The internal dynamics of the receiver GRN is shown in Figure 3a for an input AHL | ||

| + | concentration of 3. From an initial starting condition with all other states at 0, the LuxR protein | ||

| + | can be seen to rise to a stable maximum concentration of 9 molecules per cell after 100 minutes. | ||

| + | The LuxR–AHL complex also appears to have asymptotic behaviour tending to a concentration | ||

| + | of approximately 40 molecules per cell. Production of mCherry protein occurs rapidly once | ||

| + | LuxR concentration reaches a suitable level after 30 minutes. As LuxR in a living cell would | ||

| + | be maintained at a high level due to the constitutive promoter, the response would normally | ||

| + | be much quicker. With microscopes able to register individual mCherry proteins, the large | ||

| + | response to small AHL increases means the GRN behaves as we require, producing a visible | ||

| + | signal quickly. | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-ReceiverGRN.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 3a: Reciever GRN Dynamics''' - All states were given initial values of 0, apart from AHL concentration which was set to 3 molecules per cell]] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-mCherryOutput.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 3b: mCherry Output''' - Each line represents a different AHL concentration in molecules per cell]] | ||

| - | + | === Stochastic Agent Based Model === | |

| + | ==== Basic Chemotaxis Model ==== | ||

| + | To assess that the chemotaxis model was producing bacteria movement in the correct direction, | ||

| + | a simulation was created where 1000 bacteria were placed uniformly at random in an area of | ||

| + | size (100, 300) centred at the origin. A static chemotatic gradient was generated increasing in | ||

| + | the x direction and all distances were analysed using the average x component from x = 0. Each | ||

| + | simulation lasted 5 minutes and was run 300 times to allow for the distribution of movement | ||

| + | speeds to be approximated. For comparison, a control was also produced using the same | ||

| + | configuration, however, without a chemotactic gradient. | ||

| + | A time series plot of the distance travelled up the chemotatic gradient can be seen in Figure | ||

| + | 4a. This perfectly illustrates that even though chemotaxis contains stochastic elements, the | ||

| + | bias in run length permits directed movement. Also, as we would expect the control shows an | ||

| + | average distance of 0 for the entire simulation. | ||

| + | To generate the probability distribution of movement speeds, each simulation run had a line | ||

| + | of best fit calculated using least squared error. This was taken to be approximately the speed of | ||

| + | movement up the gradient. These speeds were then plotted as a histogram to give the overall | ||

| + | distribution, shown in Figure 4b. Both histograms roughly show a normal distribution with | ||

| + | mean values of 1.2mms<sup>-1</sup> and 0mms<sup>-1</sup>, for with and without chemotatic gradient respectively. | ||

| + | The standard deviation of both is also similar, approximately 0.2mms<sup>-1</sup>. | ||

| + | These results confirm that our model is producing movement in the correct direction. To | ||

| + | further verify the accuracy of the movement speeds, it would have been useful to compare our | ||

| + | values to experimental results. The difficulty in measuring the individual locations of large | ||

| + | groups of bacteria made this task prohibitive, however, may be something that could be carried | ||

| + | out in the future. | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-Chemo_TS.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 4a: Average Distance Travelled''']] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-Chemo_Dist.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 4b: Average Speed Distribution''']] | ||

| + | ==== Comparing Construction Rules ==== | ||

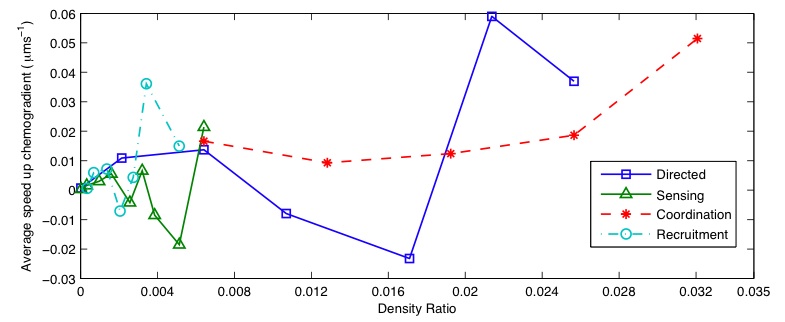

| + | To compare the efficiency of differing construction rules, we altered the bacteria density to see | ||

| + | how the average speed of particle movement was affected. Due to limited available time in running | ||

| + | the simulations, only 10 runs, of 10 minutes duration for each density could be performed | ||

| + | and the range of densities differed depending on the execution times of the simulations. For | ||

| + | example, some of the higher density directed movement simulations took 5 days to complete a | ||

| + | single run making multiple batches difficult. All densities were standardised by using the ratio | ||

| + | of bacteria and simulated environment areas. This allowed simulations with slightly differing | ||

| + | configurations to be compared without bias. Control simulations containing no chemotatic gradient for each rule type were also run and showed average speeds of approximately 0, even as bacteria density | ||

| + | increased. For this reason no further discussion of the control simulations will be made. | ||

| + | Averaged results for different densities and rules are shown in Figure 5a. Large amounts | ||

| + | of variation are present for each rule, with co-ordination the only one giving positive speeds | ||

| + | for all data points. Standard deviations of the results gave values of 0.0226 for directed movement, | ||

| + | 0.0203 for particle sensing, 0.0511 for co-ordination and 0.0140 for recruitment. Increased | ||

| + | variation is also present at lower densities. This is likely to have been caused by the number | ||

| + | of interactions between bacteria and particles being much less, allowing the random element of | ||

| + | bacteria chemotaxis to dominates the small bias in direction. | ||

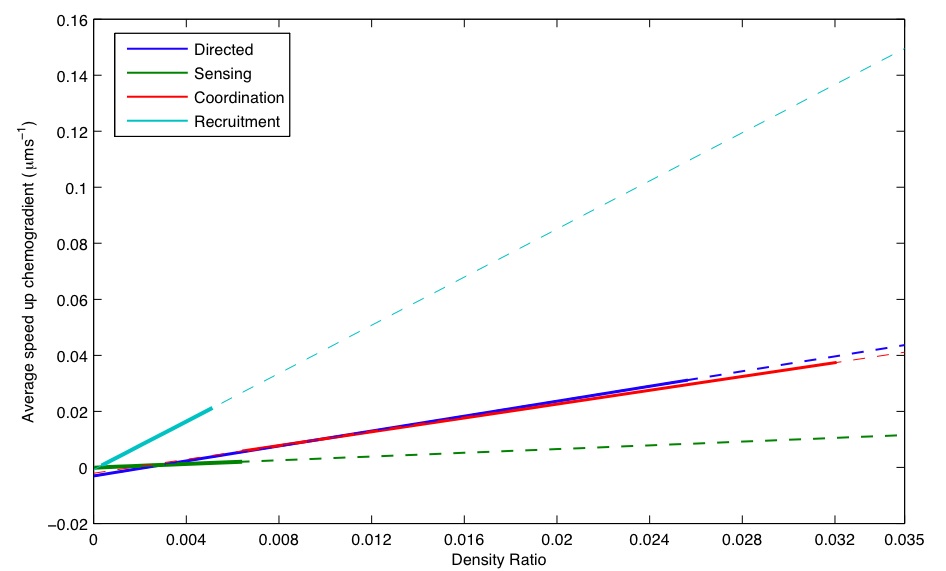

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | To perform a comparison of efficiency between rules, we considered the scaling characteristics, |

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | assuming a linear relationship between bacteria density and average particle speed. Taking |

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | the results from each individual simulation run, we fitted a least squared error line of best fit |

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | and took the gradient of this as the approximate particle speed. Another line of best fit was |

| - | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling- | + | then calculated using these approximations, leading to the overall average scaling law shown |

| + | in Figure 5b. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ordering of efficiencies seems to match what intuition would lead to. Particle sensing | ||

| + | performs the worse, most likely due to fact that bacteria will initially be performing a random | ||

| + | walk, making it equally probable that they will hit any point on a particle. As only half the | ||

| + | particle surface can impart a force in the required direction, the small bias in movement can | ||

| + | only take effect in half all collision events, reducing overall efficiency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Both short range co-ordination and directed movement produce very similar efficiencies. | ||

| + | This can be accounted for due to directed movement being an extreme case of co-ordination, | ||

| + | where the range fills the entire simulated environment. The reason for the similarity is likely | ||

| + | caused by the range used in the co-ordination simulations being large enough that densities | ||

| + | of bacteria moving towards the goal attractant are similar around the particle in both cases. | ||

| + | Bacteria moving randomly further away therefore, have little effect on the overall movement | ||

| + | speed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Long range recruitment produces what seems to be a huge improvement in efficiency. This | ||

| + | may be due to the increased density it produces near particles, however, compared to the | ||

| + | other rules the results have been generated from a very narrow range of densities. This means | ||

| + | predictions have had to be made over much greater density ratios. The major outstanding | ||

| + | question of this method is if the increased density only has beneficial effects. For example, | ||

| + | there may be a point where bacteria with bacteria interactions start to become a large factor, | ||

| + | influencing chemotaxis in a negative way. Further tests would need to be carried out to verify | ||

| + | this hypothesis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to the large variability in the underlying data, it is difficult to place any confidence on | ||

| + | the predictions of rule efficiency. To improve the accuracy of these results it would be necessary | ||

| + | to run much large sets of simulations over a wider range of densities, to ensure that the statistical | ||

| + | space is fully sampled. Even so, these preliminary studies do provide support, showing that | ||

| + | co-ordination with recruitment is likely to enable more efficient use of any available resources. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-ComparisonRulesRawResults.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 5a: Simulation Results''']] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-Comparison_Eff.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 5b: Estimated Speeds''' - Lines of best fit using least squared error were generated from data of each individual run. Solid lines represent the range of values over which data was available and dotted lines show the predicted results.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Bacteria to Particle Adhesion ==== | ||

| + | To evaluate the effect particle adhesion would have on overall movement, simulations were generated with varying numbers of bacteria randomly adhered to a single particle. The number of bacteria ranged from 1 to 15 with a static chemotatic gradient increasing in the x direction. Each configuration was run 40 times to calculate average behaviour. A control was included which omitted the chemotatic gradient. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figures 6a & 6b displays results from these simulations in terms of movement up the chemotatic | ||

| + | gradient for differing numbers of adhered bacteria, and for standard and control scenarios. | ||

| + | With a chemotatic gradient present it is evident that the bacteria are still able to carry out | ||

| + | chemotaxis, moving the particle in the correct direction. As the number of bacteria increases | ||

| + | so to does the average distance travelled by the particle. The rate of this increase is rapid for 1 | ||

| + | to 5 bacteria, however, from 6 onwards the rate decreases significantly and ordering becoming | ||

| + | mixed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When investigating this feature, video output from the simulations was consulted. These | ||

| + | illustrated that as the number of bacteria increased, the movement of each bacterium became | ||

| + | further restricted. We speculate that this interference leads to a massive decrease in variability | ||

| + | of particle movement, with the resultant force becoming an average of the group and additional | ||

| + | bacteria having less of an impact on the total resultant force. This would lead to asymptotic type | ||

| + | behaviour as the number of bacteria increases and would account for the significant drop off in | ||

| + | particle movement. Figure 7 appears to support this showing the difference in average speed | ||

| + | reducing as number of bacteria increases. To verify this claim a much larger set of simulations | ||

| + | would need to be run to better understand the exact statistics of the systems. This was not | ||

| + | possible due to time constraints on the project. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In both figures the control simulations, as expected, showed random movement about the | ||

| + | origin with average speed remaining near 0. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the interesting side effects of adhesion is the increase in efficiency of particle movement | ||

| + | speed. With each bacterium exerting a force for a longer period, when compared to | ||

| + | collision events alone, the average speed is much greater. For example, the average speed of | ||

| + | movement with adhesion remains above 0.2mms<sup>-1</sup> even with only a single bacterium adhered, | ||

| + | while our recruitment method only reaches 0.14mms<sup>-1</sup> for a density where 30% of the area | ||

| + | is bacteria. By combining adhesion with our existing construction rules it may be possible to | ||

| + | improve performance even further. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-AdhesionTS_Control.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 6a: Average Distance Travelled by Particle Time Series - Control (Without Chemotactic Gradient)''']] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-AdhesionTS_Std.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 6b: Average Distance Travelled by Particle Time Series - With Chemotactic Gradient''']] | ||

| + | [[Image:BCCS-Modelling-Adhesion.jpg|center|thumb|400px|'''Figure 7: Average Speed Comparison''' - Average particle speeds for varying numbers of adhered bacteria. Lines of best fit, using least squared error, have been used to give the overall trend]] | ||

==Simulation Movies== | ==Simulation Movies== | ||

| - | All simulation movies have been exported from BSim and require [http://www.apple.com/quicktime Quicktime] in order to be viewed. | + | All simulation movies have been exported from BSim and require [http://www.apple.com/quicktime Quicktime] in order to be viewed. They have each been compressed to reduce their size, however, please be patient when downloading as some are still quite large. |

| - | # [ | + | # [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Basic_Chemotaxis.mov '''Basic Chemotaxis'''] - Demonstrates bacteria performing chemotaxis towards a chemoattractant (increasing to the right). The trace displays the average position of all bacteria. This can be seen to move in a random manner with a bias towards the chemoattractant. |

| - | # [ | + | # [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Direct_Movement.mov '''Directed Movement'''] - Shows a particle placed in a swarm of bacteria following the chemotactic gradient. Collisions between bacteria and the particle result in a net movement up the chemotactic gradient. |

| - | # [ | + | # [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Coordination.mov '''Short Range Co-ordination'''] - Bacteria are initially not responsive to the chemoattractant. On coming into contact with the particle, a bacterium's chemotactic response is switched on. At the same time a quorum based signal is produced by the bacteria that are in contact with the particle. Neighbouring bacteria switch from a random walk to a chemotactic response on sensing the quorum based signal. |

| - | # [ | + | # [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Recruitment.mov '''Long Range Recruitment'''] - The bacteria act as above but on contact with the particle also produce a long range chemotactic based signal, recruiting distant bacteria towards the particle. |

| - | # [ | + | # [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Adhesion.mov '''Bacteria to Particle Adhesion'''] - Bacteria are adhered to the particle and follow a chemotactic gradient. |

| - | == Software == | + | == Software Download == |

| - | [ | + | To download both compiled versions of BSim and the source code for both BSim and the MATLAB GRN models see our [[Team:BCCS-Bristol/Modeling-Software|'''Software Download Page''']]. |

== Modelling Notebook == | == Modelling Notebook == | ||

Latest revision as of 15:01, 22 October 2008

|

Approach

Due to the nature of this project, a wide range of modelling techniques are required to help understand ideas and guide experimentation in the wet lab. The reason for this is that in addition to the creation of synthetic genetic circuits to regulate the internal state of a cell, we require the cell to physically interact with the environment in such a way that by bringing a large number of them together, all following to same rules, emergent behaviours are exhibited - the ultimate outcome of the project. To do this it is necessary to take into consideration the movement (chemotaxis) and physical force exerted between large numbers of cells in an environment as well as other aspects such as chemical diffusion, fluid dynamics and individual cell states.

For these reasons we will be developing two types of model, an internal representation of a single bacterium using differential equations, and a external representation of the system as a whole using computerised stochastic agents. This will allow us to gain a better understanding of the different aspects of the project in a manageable way. Once these models have been completed, in an attempt to combine the advantages of each, both will be combined to give a holistic view of the modelling from a single cell to the whole population.

Both types of model will make heavy use of computing resources. We are looking to utilise MATLAB for tasks such as numerical integration and statistical analysis and Java for the development of a stochastic agent based framework that will allow us to simulate bacterial chemotaxis, physical interactions between bacteria/particles and chemical fields exhibiting diffusion. The simulation environment will form the majority of the modelling work and once we can incorporate the GRN dynamics within each bacterium (agent) we hope to be able to perform virtual experiments that mimic those in the wet lab.

The major limitiation of this approach is that the simulation of huge numbers of bacteria requires huge amounts of computing power. This means that for any reasonably sized simulations we will have to seriously consider optimising our code to make most efficient use of local resources (e.g. multi-threading for multiple processor/core machines) and for larger simulations allow for execution on distributed computing architectures. With this in mind we are aiming to gain access to the [http://www.acrc.bris.ac.uk/acrc/hpc.htm Blue Crystal] high performance computing cluster at the university to attempt some large scale simulations.

Models

|  |  |

| | | |

| To understand the dynamics of genetic networks that we design, differental equations are used to model the changes in concentration of mRNA and proteins. | With the project requiring global behaviour to emerge via the physical en masse movement of bacteria, stochastic agent based simulations are used to investigate the viability and limits of different approaches. | With the aim of improving simulation accuracy this model integrates the intercellular GRN dynamics with the extra-cellular interactions of the stochastic agent based simulation. |

Results

Gene Regulatory Network

Sender

To assess the sender GRN we were interested in how the strength of the response regulator CpMax affects the overall dynamics and the final output of AHL. For a CpMax range of [0.1, 100] the qualitative behaviour of the GRN was the same, shown in Figure 1a for a CpMax value of 5 molecules per cell. Both GFP and LuxI proteins rise rapidly in the first hour, while CpxR and LuxI mRNA reaches a maximum after 60 minutes. The final LuxI mRNA concentration is low, causing the rate of increase in LuxI protein to slow towards the end of the simulation. In contrast, both mRNA and protein concentrations of GFP continue to increase rapidly for the duration.

Figure 1b shows how the initial CpMax value effects AHL output over time. The behaviour is seen to be asymptotic, tending to a final concentration after approximately 400 minutes. The relationship between CpMax and AHL appears to be non-linear, with a rapid increase seen between 0.1 and 1. After this point the rate seems to slows, reaching a maximum near 4300. The huge variability in output AHL, even when the initial CpMax value is only varied by a small amount, makes it difficult to estimate a realistic output for a single cell. Experimental techniques would need to be used to refine the accuracy of these results and allow for an appropriate CpMax value to be chosen. Overall, the GRN exhibits the correct dynamics, giving a sizeable AHL production in the presence of a CpxR response.

Transport

For the transport aspect of the system we investigated how the concentration distribution varied over time. A delta input of size 50 was used and the concentration distribution calculated over a 30 minute period. Figure 2 shows the distribution at 5 minute intervals. A value of 0.23 s-1 was selected for the diffusion co-efficient. As we do not know the maximal expression level CpMax of the response regulator CpxR it was difficult to estimate the rate that an individual cell would produce AHL. For this reason we attempted to concentrate on understanding the distance over which a threshold value was exceeded. The receiver GRN has been shown to be sensitive to low levels of AHL, see previous section, and so we assumed a large response would occur at concentrations of 3 and greater.

Reciever

For the receiver we wanted to understand how varying AHL concentration altered output of our signalling protein mCherry. This relationship is shown in Figure 3b. Availability of any AHL causes a large increase in mCherry output, however, the rate of increase decays exponentially. Output increases very little once a concentration of 3 molecules per cell has been reached. The internal dynamics of the receiver GRN is shown in Figure 3a for an input AHL concentration of 3. From an initial starting condition with all other states at 0, the LuxR protein can be seen to rise to a stable maximum concentration of 9 molecules per cell after 100 minutes. The LuxR–AHL complex also appears to have asymptotic behaviour tending to a concentration of approximately 40 molecules per cell. Production of mCherry protein occurs rapidly once LuxR concentration reaches a suitable level after 30 minutes. As LuxR in a living cell would be maintained at a high level due to the constitutive promoter, the response would normally be much quicker. With microscopes able to register individual mCherry proteins, the large response to small AHL increases means the GRN behaves as we require, producing a visible signal quickly.

Stochastic Agent Based Model

Basic Chemotaxis Model

To assess that the chemotaxis model was producing bacteria movement in the correct direction, a simulation was created where 1000 bacteria were placed uniformly at random in an area of size (100, 300) centred at the origin. A static chemotatic gradient was generated increasing in the x direction and all distances were analysed using the average x component from x = 0. Each simulation lasted 5 minutes and was run 300 times to allow for the distribution of movement speeds to be approximated. For comparison, a control was also produced using the same configuration, however, without a chemotactic gradient. A time series plot of the distance travelled up the chemotatic gradient can be seen in Figure 4a. This perfectly illustrates that even though chemotaxis contains stochastic elements, the bias in run length permits directed movement. Also, as we would expect the control shows an average distance of 0 for the entire simulation. To generate the probability distribution of movement speeds, each simulation run had a line of best fit calculated using least squared error. This was taken to be approximately the speed of movement up the gradient. These speeds were then plotted as a histogram to give the overall distribution, shown in Figure 4b. Both histograms roughly show a normal distribution with mean values of 1.2mms-1 and 0mms-1, for with and without chemotatic gradient respectively. The standard deviation of both is also similar, approximately 0.2mms-1. These results confirm that our model is producing movement in the correct direction. To further verify the accuracy of the movement speeds, it would have been useful to compare our values to experimental results. The difficulty in measuring the individual locations of large groups of bacteria made this task prohibitive, however, may be something that could be carried out in the future.

Comparing Construction Rules

To compare the efficiency of differing construction rules, we altered the bacteria density to see how the average speed of particle movement was affected. Due to limited available time in running the simulations, only 10 runs, of 10 minutes duration for each density could be performed and the range of densities differed depending on the execution times of the simulations. For example, some of the higher density directed movement simulations took 5 days to complete a single run making multiple batches difficult. All densities were standardised by using the ratio of bacteria and simulated environment areas. This allowed simulations with slightly differing configurations to be compared without bias. Control simulations containing no chemotatic gradient for each rule type were also run and showed average speeds of approximately 0, even as bacteria density increased. For this reason no further discussion of the control simulations will be made.

Averaged results for different densities and rules are shown in Figure 5a. Large amounts of variation are present for each rule, with co-ordination the only one giving positive speeds for all data points. Standard deviations of the results gave values of 0.0226 for directed movement, 0.0203 for particle sensing, 0.0511 for co-ordination and 0.0140 for recruitment. Increased variation is also present at lower densities. This is likely to have been caused by the number of interactions between bacteria and particles being much less, allowing the random element of bacteria chemotaxis to dominates the small bias in direction.

To perform a comparison of efficiency between rules, we considered the scaling characteristics, assuming a linear relationship between bacteria density and average particle speed. Taking the results from each individual simulation run, we fitted a least squared error line of best fit and took the gradient of this as the approximate particle speed. Another line of best fit was then calculated using these approximations, leading to the overall average scaling law shown in Figure 5b.

The ordering of efficiencies seems to match what intuition would lead to. Particle sensing performs the worse, most likely due to fact that bacteria will initially be performing a random walk, making it equally probable that they will hit any point on a particle. As only half the particle surface can impart a force in the required direction, the small bias in movement can only take effect in half all collision events, reducing overall efficiency.

Both short range co-ordination and directed movement produce very similar efficiencies. This can be accounted for due to directed movement being an extreme case of co-ordination, where the range fills the entire simulated environment. The reason for the similarity is likely caused by the range used in the co-ordination simulations being large enough that densities of bacteria moving towards the goal attractant are similar around the particle in both cases. Bacteria moving randomly further away therefore, have little effect on the overall movement speed.

Long range recruitment produces what seems to be a huge improvement in efficiency. This may be due to the increased density it produces near particles, however, compared to the other rules the results have been generated from a very narrow range of densities. This means predictions have had to be made over much greater density ratios. The major outstanding question of this method is if the increased density only has beneficial effects. For example, there may be a point where bacteria with bacteria interactions start to become a large factor, influencing chemotaxis in a negative way. Further tests would need to be carried out to verify this hypothesis.

Due to the large variability in the underlying data, it is difficult to place any confidence on the predictions of rule efficiency. To improve the accuracy of these results it would be necessary to run much large sets of simulations over a wider range of densities, to ensure that the statistical space is fully sampled. Even so, these preliminary studies do provide support, showing that co-ordination with recruitment is likely to enable more efficient use of any available resources.

Bacteria to Particle Adhesion

To evaluate the effect particle adhesion would have on overall movement, simulations were generated with varying numbers of bacteria randomly adhered to a single particle. The number of bacteria ranged from 1 to 15 with a static chemotatic gradient increasing in the x direction. Each configuration was run 40 times to calculate average behaviour. A control was included which omitted the chemotatic gradient.

Figures 6a & 6b displays results from these simulations in terms of movement up the chemotatic gradient for differing numbers of adhered bacteria, and for standard and control scenarios. With a chemotatic gradient present it is evident that the bacteria are still able to carry out chemotaxis, moving the particle in the correct direction. As the number of bacteria increases so to does the average distance travelled by the particle. The rate of this increase is rapid for 1 to 5 bacteria, however, from 6 onwards the rate decreases significantly and ordering becoming mixed.

When investigating this feature, video output from the simulations was consulted. These illustrated that as the number of bacteria increased, the movement of each bacterium became further restricted. We speculate that this interference leads to a massive decrease in variability of particle movement, with the resultant force becoming an average of the group and additional bacteria having less of an impact on the total resultant force. This would lead to asymptotic type behaviour as the number of bacteria increases and would account for the significant drop off in particle movement. Figure 7 appears to support this showing the difference in average speed reducing as number of bacteria increases. To verify this claim a much larger set of simulations would need to be run to better understand the exact statistics of the systems. This was not possible due to time constraints on the project.

In both figures the control simulations, as expected, showed random movement about the origin with average speed remaining near 0.

One of the interesting side effects of adhesion is the increase in efficiency of particle movement speed. With each bacterium exerting a force for a longer period, when compared to collision events alone, the average speed is much greater. For example, the average speed of movement with adhesion remains above 0.2mms-1 even with only a single bacterium adhered, while our recruitment method only reaches 0.14mms-1 for a density where 30% of the area is bacteria. By combining adhesion with our existing construction rules it may be possible to improve performance even further.

Simulation Movies

All simulation movies have been exported from BSim and require [http://www.apple.com/quicktime Quicktime] in order to be viewed. They have each been compressed to reduce their size, however, please be patient when downloading as some are still quite large.

- [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Basic_Chemotaxis.mov Basic Chemotaxis] - Demonstrates bacteria performing chemotaxis towards a chemoattractant (increasing to the right). The trace displays the average position of all bacteria. This can be seen to move in a random manner with a bias towards the chemoattractant.

- [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Direct_Movement.mov Directed Movement] - Shows a particle placed in a swarm of bacteria following the chemotactic gradient. Collisions between bacteria and the particle result in a net movement up the chemotactic gradient.

- [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Coordination.mov Short Range Co-ordination] - Bacteria are initially not responsive to the chemoattractant. On coming into contact with the particle, a bacterium's chemotactic response is switched on. At the same time a quorum based signal is produced by the bacteria that are in contact with the particle. Neighbouring bacteria switch from a random walk to a chemotactic response on sensing the quorum based signal.

- [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Recruitment.mov Long Range Recruitment] - The bacteria act as above but on contact with the particle also produce a long range chemotactic based signal, recruiting distant bacteria towards the particle.

- [http://2008sw.igem.org/bccs_bristol/media/BCCS-Modelling-Adhesion.mov Bacteria to Particle Adhesion] - Bacteria are adhered to the particle and follow a chemotactic gradient.

Software Download

To download both compiled versions of BSim and the source code for both BSim and the MATLAB GRN models see our Software Download Page.

Modelling Notebook

- Progress Report - To track our progress see our weekly reports. These let you know what we have been up to, including comments on the reasons behind any important decisions that were made.

- Modelling Parameters - Full listings of all parameters investigated for the modelling part of the project, with values that have been chosen, reasons for their selection and references to the original sources.

- To Do List - List of items that need to be done on the modelling and simulation.

- Batch Simulations - Outline of all simulations we intend to run.

"

"