Team:Heidelberg/Project/Sensing

From 2008.igem.org

(→Introduction) |

(→Project - Sensing) |

||

| Line 483: | Line 483: | ||

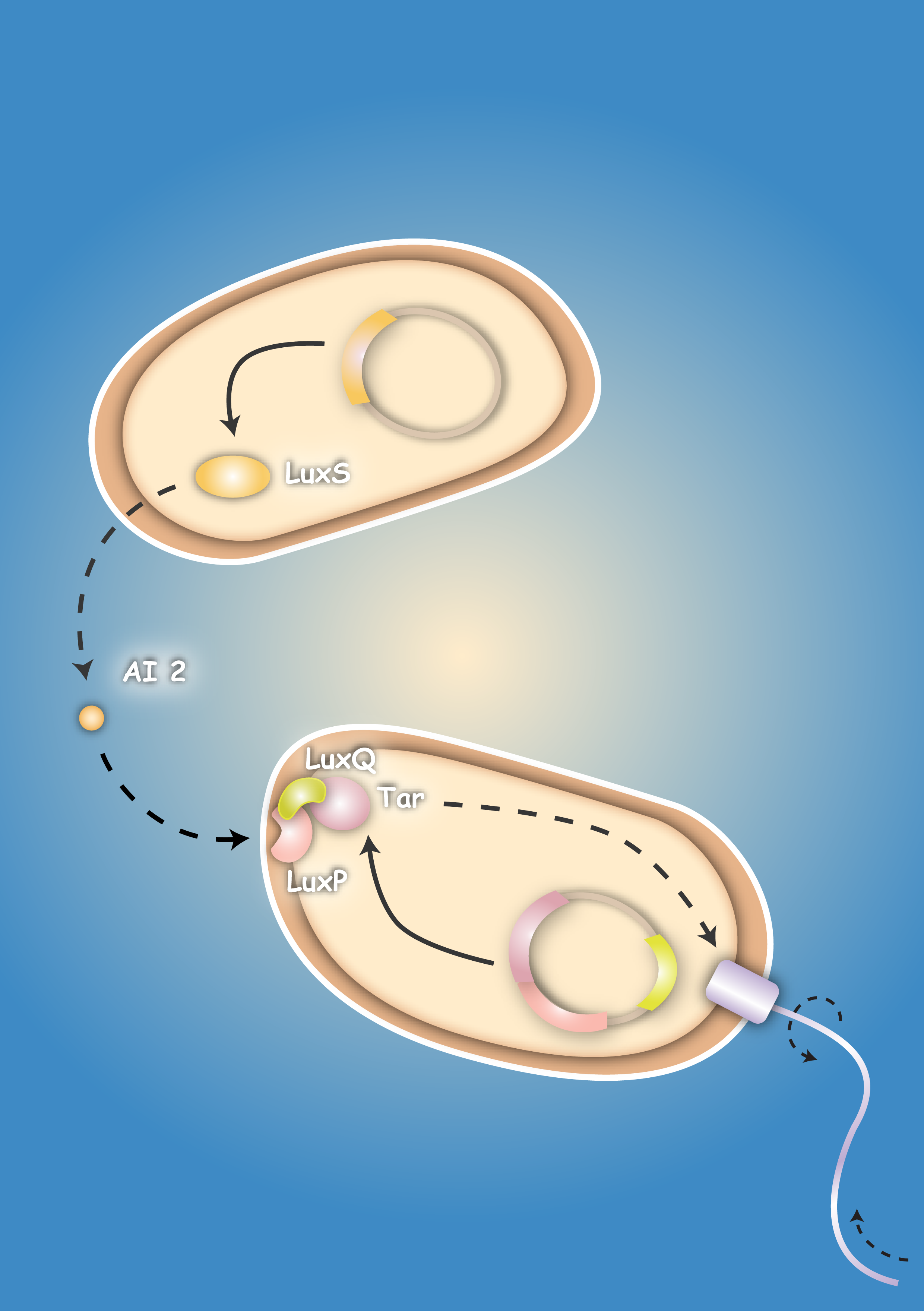

Many bacteria use a mechanism called quorum sensing for the coordination of their gene expression in a population according to cell density. This allows bacteria to synchronize their behavior and lets them act to a certain extend similar to multicellular organisms [Waters & Bassler, 2005; Vendeville, 2005]. | Many bacteria use a mechanism called quorum sensing for the coordination of their gene expression in a population according to cell density. This allows bacteria to synchronize their behavior and lets them act to a certain extend similar to multicellular organisms [Waters & Bassler, 2005; Vendeville, 2005]. | ||

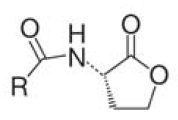

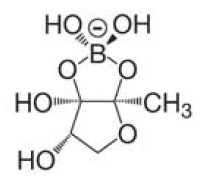

A major role in this process play small diffusible molecules, called Autoinducers (AI), which are secreted by the cells and can be detected by other bacteria to sense cell density. There are two major signaling molecules involved in quorum-sensing, AI-1 and AI-2. AI-1 is a acyl-homoserine lactone and AI- 2 is a furanosyl-borate-diester [Sun, 2004]. For the chemical structure of these molecules see figure 3 and 4.[[Image:HD AHL.png|right|thumb|150px|'''Fig.3''': Core structure of AI-1 [Waters & Bassler, 2005]]][[Image:HD AI-2.png|right|thumb|150px|'''Fig. 4''': Structure of AI-2 from V. harveyi. [Waters & Bassler, 2005]]] While AI-1 was found to be responsible for the intraspecies communication, i.e. within one species, AI-2 which is shared by both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, allows cross-talk among different species (interspecies communication)[DeKeersmaecker, 2006]. | A major role in this process play small diffusible molecules, called Autoinducers (AI), which are secreted by the cells and can be detected by other bacteria to sense cell density. There are two major signaling molecules involved in quorum-sensing, AI-1 and AI-2. AI-1 is a acyl-homoserine lactone and AI- 2 is a furanosyl-borate-diester [Sun, 2004]. For the chemical structure of these molecules see figure 3 and 4.[[Image:HD AHL.png|right|thumb|150px|'''Fig.3''': Core structure of AI-1 [Waters & Bassler, 2005]]][[Image:HD AI-2.png|right|thumb|150px|'''Fig. 4''': Structure of AI-2 from V. harveyi. [Waters & Bassler, 2005]]] While AI-1 was found to be responsible for the intraspecies communication, i.e. within one species, AI-2 which is shared by both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, allows cross-talk among different species (interspecies communication)[DeKeersmaecker, 2006]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| Line 490: | Line 488: | ||

To ensure the proper folding and chemotactic activity of our chimeric receptors we will engineer two different fusion sequences: | To ensure the proper folding and chemotactic activity of our chimeric receptors we will engineer two different fusion sequences: | ||

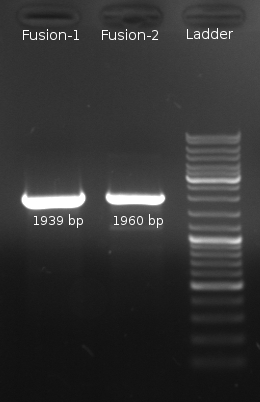

| - | The first one (Fusion 1) will contain the complete N-terminal part of the LuxQ receptor until the end of its second transmembrane domain fused to the cytoplasmic domain (a.a. 213-553) of the Tar receptor. The second (Fusion 2) will consist of the first transmembrane domain and the periplasmic ligand binding domain of LuxQ followed by the second transmembrane (a.a.189-212) and the cytoplasmic domain of the Tar receptor (for illustration of chimeric receptors see [[Team:Heidelberg/Notebook/Sensing_Group/Cloning | cloning strategy]]) | + | The first one (Fusion 1) will contain the complete N-terminal part of the LuxQ receptor until the end of its second transmembrane domain fused to the cytoplasmic domain (a.a. 213-553) of the Tar receptor. The second (Fusion 2) will consist of the first transmembrane domain and the periplasmic ligand binding domain of LuxQ followed by the second transmembrane (a.a.189-212) and the cytoplasmic domain of the Tar receptor (for illustration of chimeric receptors see [[Team:Heidelberg/Notebook/Sensing_Group/Cloning | cloning strategy]]). |

Revision as of 22:51, 29 October 2008

Contents |

Project - Sensing

Abstract

Bacteria have the ability to sense gradients of chemoeffectors in their environment by specific receptor molecules which are present in the bacteria membrane. Our aim was to take advantage of bacterial chemotaxis in order to generate a "killer" strain which is able to detect and finally kill a "prey" strain by chemotaxis induced movement towards it. For this purpose we cloned the LuxS gene of Vibrio harveyi in an expression plasmid. LuxS encodes the Autoinducer-2 synthase, an enzyme that is essential for the production of the chemoattractant Autoinducer-2 (AI-2). We wanted to transform the "prey" cells with this expression plasmid in order to establish a concentration gradient of AI-2, which can be sensed by the "killer" strain. To make the "killer" strain sensitive towards AI-2, we generated two different chimeric receptors consisting each of the periplasmic ligand-binding domain of LuxQ, the natural receptor for AI-2, and the cytoplasmic part of the chemotaxis receptor (Tar). To allow proper folding and signal transduction we included either the second transmembrane domain of the LuxQ receptor or the Tar receptor in the chimeric receptor sequence. In addition to the chimeric receptor sequence we wanted to co-express from the same plasmid also LuxP, a cofactor which is essential for AI-2 ligand binding of the LuxQ receptor. We were successful in the cloning of all constructs mentioned above. The chimeric receptors were expressed in transformed bacteria as controlled by receptor fusions to the yellow fluorescent protein YFP. To our surprise none of the chimeric receptor constructs showed a polarized localization as expected for chemotaxis receptors. We were also not able to detect chemotactic activity in the transformed bacteria. Future experiments with sequence optimized receptor fusions will have to show if AI-2 is able to induce Tar-based chemotaxis. [back]

Introduction

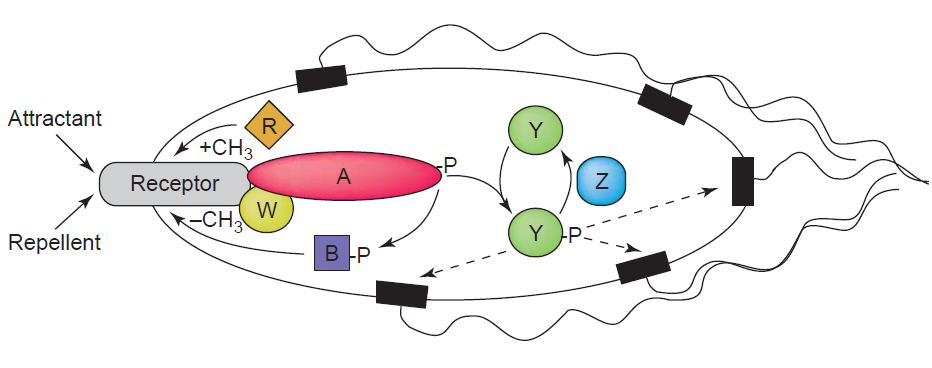

Chemotaxis enables bacteria to swim towards or away from a concentration gradient of chemoeffector molecules, which can be either chemoattractants or repellants. The best understood and characterized model for the investigation of chemotaxis is that of E.coli. It is known that the presence of an attractant can cause E.coli to swim (run) towards the source by the flagellar rotation in a counterclockwise manner. This swimming is interupted by short phases of tumbling caused by the clockwise rotation of the flagellar motor. The swimming direction is chosen randomly, but swimming towards the attractanct source leads to the shortening of the tumbling periods thereby resulting in a positive movement towards the attractant. The Tar receptor which is also used in our studies represents one of the most abundant chemotaxis receptor molecules of E. coli. It usually can be activated by aspartate binding. The receptor activation leads to the induction of signaling events that involve as in all signal transduction systems the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of regulatory target proteins. In case of the Tar receptor, upon ligand binding the adaptor protein CheW and CheA, a histidine kinase, are recruited to the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor. While attractants inhibit the autophosphorylation of the effector protein CheA, the presence of repellants promote this process and cause the rapid transfer of the phosphoryl group to the protein CheY. Phosphorylated CheY then initiates after diffusion to the flagellar motor the change in flagellar motion orientation leading to bacteria tumbling due to a clockwise flagellar motion. Reajustment of the system is efficiently controlled by the phosphatase CheZ which can quickly remove the phosphoryl group from CheY. Adaptation of the system is mediated by two proteins called CheR and CheB (Sourjik, 2004). For a schematic presentation of the chemotaxis signaling in E.coli see figure 1.

[back]

Many bacteria use a mechanism called quorum sensing for the coordination of their gene expression in a population according to cell density. This allows bacteria to synchronize their behavior and lets them act to a certain extend similar to multicellular organisms [Waters & Bassler, 2005; Vendeville, 2005].

A major role in this process play small diffusible molecules, called Autoinducers (AI), which are secreted by the cells and can be detected by other bacteria to sense cell density. There are two major signaling molecules involved in quorum-sensing, AI-1 and AI-2. AI-1 is a acyl-homoserine lactone and AI- 2 is a furanosyl-borate-diester [Sun, 2004]. For the chemical structure of these molecules see figure 3 and 4. While AI-1 was found to be responsible for the intraspecies communication, i.e. within one species, AI-2 which is shared by both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, allows cross-talk among different species (interspecies communication)[DeKeersmaecker, 2006].

The main objective of our project is to engineer a so called killer strain of E.coli which would be able to swim by chemotaxis towards a “prey” strain which secretes a specific chemoattractant. We want to link quorum sensing features of receptor molecules to chemotactic activity of bacteria. In more detail, we want to generate chimeric receptors composed of the ligand binding domain of LuxQ, a receptor involved in quorum sensing via Autoinducer-2 (AI-2) in Vibrio bacteria fused to the cytoplasmic domain of the chemotaxis receptor Tar. Both receptors share structural similarities: a very small cytoplasmic domain is followed by the first transmembrane domain, TM1, and the periplasmic domain, which is a less conserved region responsible for ligand binding. This domain is followed by a second transmembrane domain, TM2 and finally the cytoplasmic domain to which interacting proteins are recruited.

To ensure the proper folding and chemotactic activity of our chimeric receptors we will engineer two different fusion sequences: The first one (Fusion 1) will contain the complete N-terminal part of the LuxQ receptor until the end of its second transmembrane domain fused to the cytoplasmic domain (a.a. 213-553) of the Tar receptor. The second (Fusion 2) will consist of the first transmembrane domain and the periplasmic ligand binding domain of LuxQ followed by the second transmembrane (a.a.189-212) and the cytoplasmic domain of the Tar receptor (for illustration of chimeric receptors see cloning strategy).

These chimeric receptors will then be expressed in our “killer” cells together with LuxP, a protein which is needed for the proper binding of AI-2 to the receptor. The LuxP gene will be cloned from the Vibrio harveji genome. The presence of the chimeric receptors will allow the killer cells to sense concentration gradients of AI-2 established by the “prey” cells. In this context the “prey” cells will be transformed with an expression plasmid encoding LuxS, an the Autoinducer-2 synthase essential for the synthesis of AI-2. We will analyse the correct receptor localization by the expression of fusions of the two different chimeric receptors to a fluorescent protein. In this context we will also analyse the receptor functionality. In parallel we want to test the functionality of our "prey-killer" system by swarm assays. Once we have established this system, we will perform 4D microscopy to quantitatively characterize our "prey-killer" system in a time resolved manner.

[back]

Results

We successfully cloned both chimeric constructs, F1 and F1, into our expression plasmid pDK48 in HCB33 or pBAD33 in UU1250 strain. In addition to our chimeric receptor sequence this plasmid encoded also LuxP, the protein which is essential for AI-2 binding of the LuxQ receptor. In order to verify the expression of the chimeric receptor proteins and to control the correct localization of the receptor molecules in our prey cells, we transfomed DH5α cells with the chimera constructs fused to the yellow fluorescent protein YFP. Expression of this construct was verified by a detectable fluorecence signal in the transformed cells. However, when tested in swarm assays the transformed bacteria showed no chemotactic activity. This was observed for both the UU1250 strain and the HCB33 strain. That the chimeric receptors did not show any chemotactic activity was further confirmed by polarisation tests. Therefore we coexpressed the unlabeled receptors in UU1250 cells together with YFP-CheA. The CheA fusion was thereby expected to localize to the cytoplasmic part of the receptors and subsequently fluorescent signals should be visible at the cell membrane [Bourret, 1993; Morrison & Parkinson]. Nevertheless, no membrane localization of fluorescence could be detected. The reason remains unclear, but we assume that either the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor was not able to bind YFP-CheA properly or the receptor did not localize to the membrane at all. We have further performed kinase-activity tests, but these also did not show any positive results. [back]

Discussion

Our aim was to generate a new chemotactic receptor chimera consisting of parts of the LuxQ receptor and the well studied Tar receptor. This kind of receptor would allow bacteria to sense gradients of the autoinducer molecule AI-2 and swim towards the gradient due to the Tar receptor part. In order to allow the correct folding and activation of the tar receptor in the cytoplasm we included either the second transmembrane domain of the LuxQ receptor or the Tar receptor. We could conclude from our expression tests in different bacteria that both chimeric receptors were expressed from the transformed plasmids. Nevertheless none of the chimeras showed a polarization at one pole of the bacteria cells. This finding was confirmed by our swarm assays where the transformed bacteria did not show any chemotactic movement towards the source of AI-2 while control bacteria did. We can only speculate that our chimeric receptor is not correctly inserted and located within the bacteria membrane due to the presence of the periplasmic domain of LuxQ. We plan to insert flexible linker sequences of different sizes between the LuxQ sensing domain and the Tar receptor transmembrane part, which would allow a correct folding of the receptor molecules. If we are thereby able to ensure the proper localization of the chimeric receptor molecules, the next step would be to mutate the linker region of the Tar receptor randomly in order to optimize its signal transduction properties. [back]

References

[Waters & Bassler, 2005] Christopher M. Waters, and Bonnie L. Bassler: Quorum Sensing: Cell-to-Cell Communication in Bacteria, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 319–346, 2005

[Sourjik, 2004] Victor Sourjik: Receptor clustering and signal processing in E. coli chemotaxis, Trends in Microbiology 12(12), 569–576, December 2004

[Vendeville, 2005] Agnes Vendeville, Klaus Winzer, Karin Heurlier, Christoph M. Tang, and Kim R. Hardie: Making sense of metabolism: Autoinducer-2, LuxS and pathogenic bacteria, Nature Reviews 3, 383–396, 2005

[Wadhams, 2004] George H. Wadhams, and Judith P. Armitage: Making Sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis, Molecular Cell Biology 5, 1024–1037, December 2004

[Mowbray, 1998] Sherry L. Mowbray, and Mats O. J. Sandgren: Chemotaxis Receptors: A progress report on structure and function, Journal of Structural Biology 124, 257–275, 1998

[DeKeersmaecker, 2006] Sigrid C. J. De Keersmaecker, Kathleen Sonck, and Jos Vanderleyden: Let LuxS speak up in AI-2 signaling, Trends in Microbiology 14(3), 114–119, 2006

[Sun, 2004] Jibin Sun, Rolf Daniel, Irene Wagner-Döbler, and An-Ping Zeng: Is autoinducer-2 a universal signal for interspecies communication: a comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of the synthesis and signal transduction pathways, BMC Evolutionary Biology 4(36), 2004

[Neiditch, 2005] Matthew B. Neiditch, Michael J. Federle, Stephan T. Miller, Bonnie L. Bassler, and Frederick M. Hughson: Regulation of LuxPQ Receptor Activity by the Quorum-Sensing Signal Autoinducer-2, Molecular Cell 18, 507–518, May 2005

[Bourret, 1993] R B Bourret, J Davagnino, and M I Simon: The carboxy-terminal portion of the CheA kinase mediates regulation of autophosphorylation by transducer and CheW, Journal of Bacteriology 175, 2097–2101, 1993

[Morrison & Parkinson] TB Morrison, and JS Parkinson: A fragment liberated from the Escherichia coli CheA kinase that blocks stimulatory, but not inhibitory, chemoreceptor signaling, Journal of Bacteriology 179, 5543–5550, 1997 [back]

"

"