Team:Harvard/Hardware

From 2008.igem.org

m (→Software) |

(→Software) |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

==Motivation== | ==Motivation== | ||

| - | The broad goal of our project was to engineer | + | The broad goal of our project was to engineer ''S. Oneidensis'' to produce a detectable change in electric current in response to some environmental stimulus. In order to observe such a reaction, our first task was to design an environment capable of housing bacteria and measuring current production. |

==Solution - Microbial Fuel Cells== | ==Solution - Microbial Fuel Cells== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

===Background=== | ===Background=== | ||

| - | + | To measure the electric current production in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, we constructed microbial fuel cells (MFCs) to harvest the electricity produced. Traditional fuel cells convert chemical energy to electrical energy. MFCs are unique in that the fuel source used is microbially degradable organic matter (Lovley 2006). Such organic matter is a form of renewable energy and can come from materials in wastewater, sediments, or agricultural wastes (Cho et al. 2007). Compared to hydrogen- and methanol-driven fuel cells, MFCs are particular attractive due to their ease of operation and wide range of fuel sources available. They do not require expensive catalysts, high operating temperatures, nor explosive or toxic fuels (Lovley 2006). Indeed, we found the construction and operation of our microbial fuel cells to be relatively straightforward. | |

| - | [[Image: | + | |

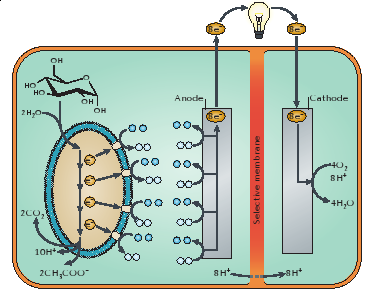

| + | MFCs operate using principles similar to normal fuel cells. MFCs require an anode and a cathode separated by a semi-permeable membrane (permeable to protons) (Lovley 2006). The anode compartment is generally anaerobic and is the site of oxidation of organic matter (Lovley 2006); the cathode transfers electrons to the electron acceptor (Lovley 2006). MFCs take advantage of the natural metabolism of microorganisms that break down organic matter by intercepting the electrons that would be donated to naturally occurring electron acceptors. Instead, these electrons are transferred from the anode to the cathode, usually along metal wires to which current readings can be taken. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A figure of a microbial fuel cell is shown below (NB: this is not what we used in our experiments). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[ Image: Snapshot1.png | 350px ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the anode side, glucose is being metabolized by the microorganism to yield electrons which are transferred to the cathode side where oxygen is reduced to water (Lovley 2006). | ||

===Context=== | ===Context=== | ||

| + | |||

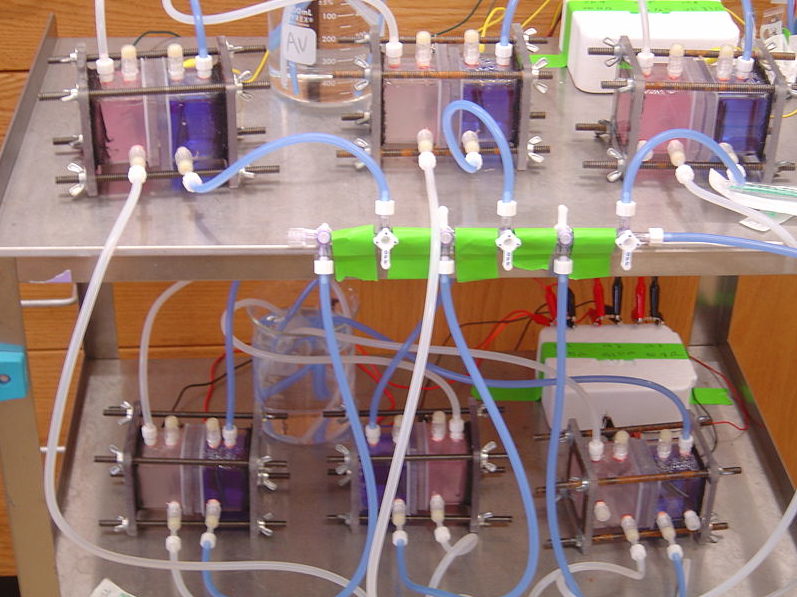

| + | Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is a suitable microorganism for a MFC. It is known to break down lactate (Bretschger et al. 2007), and in anaerobic conditions, S. oneidensis MR-1 produces nanowires that shuttle electrons to electron acceptors as its aerobic electron acceptor, oxygen, is unavailable (Gorby et al. 2006). Taking advantage of this, we designed our microbial fuel cell with an anaerobic anode where completion of the lactate reduction pathway must be completed by transferring electrons to the cathode side at which reduction of oxygen to water occurs. The anode chamber, besides housing our bacteria, was also the site of chemical injections. We provided S. oneidensis MR-1 with lactate as its sole carbon source and sought to induce the mtrB gene, thus “turning on” current production, with chemicals such as lactose and tetracycline. In addition, our heat tests were directed towards the anode chamber as well. Thus, the detection of electricity production of S. oneidensis MR-1 using MFCs serves as an innovative way to detect gene expression, combining both traditional molecular biology with renewable energy engineering. | ||

| + | [[Image:Chambers.jpg|600px]] | ||

==Design Goal== | ==Design Goal== | ||

| Line 83: | Line 93: | ||

* anaerobic/aerobic | * anaerobic/aerobic | ||

| - | + | S. oneidensis MR-1 only oxidizes substrates in anaerobic environments. The chambers housing the bacteria must be oxygen free and airtight. | |

* sterile | * sterile | ||

| Line 92: | Line 102: | ||

* accessible | * accessible | ||

| - | Experimenters must have access to the bacterial environment. | + | Experimenters must have access to the bacterial environment. |

| - | + | ||

==Approach== | ==Approach== | ||

| Line 104: | Line 113: | ||

====Fuel Cells==== | ====Fuel Cells==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fuel cells were constructed to provide an environment in which bacteria could live and produce electric current. After researching various microbial fuel cell designs, we concluded that a two chamber system would best suit our goals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The simple picture of our design was a hollow tube, sealed at both ends with endplates, and cut in half horizontally to allow for insertion of a semi-permeable membrane. The two halves would then be clamped back together to close the system. Ports needed to be drilled into the walls of the tube to allow for insertion of the anode and cathode, as well as to initially fill the sealed chambers with media and inject bacteria and food. Previous research suggested bubbling gasses into the chambers could improve performance. In the anode chamber, nitrogen was typically bubbled to purge the chamber of oxygen, keeping the bacteria in a controlled anaerobic environment. In the cathode chamber, air was typically bubbled to provide a continuous source of oxygen, ensuring an efficient reduction reaction. We decided to include ports for gas inlet and outlet as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Materials for the chamber were then selected. The central tube and endplates were made from polycarbonate. This is a clear, hard plastic that is easily bonded to itself with silicone glue. It has the added benefit of allowing visual monitoring of the chambers, it is easily milled, and it can be autoclaved. Silicone was used in glue form to bond the tubes to their endplates, and it was used in solidified from to construct gaskets which sealed the two chambers together when clamped. The clamping mechanism involved drilling holes through the overlap of the endplates, inserting iron threaded rods down the length of the chambers, and fastening the ends of the rods with wing nuts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The anode material was chosen to provide maximal surface area and attachment sites for bacteria. Carbon felt provided such a surface. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The cathode material needed to provide an efficient surface for the reduction reactions to take place. Platinum on carbon cloth acted as a catalyst for this reaction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Titanium wire was used to connect the cathode and anode surfaces to an external resistor as it cannot be oxidized, which would interfere with the reactions. | ||

====Measurement==== | ====Measurement==== | ||

| Line 120: | Line 141: | ||

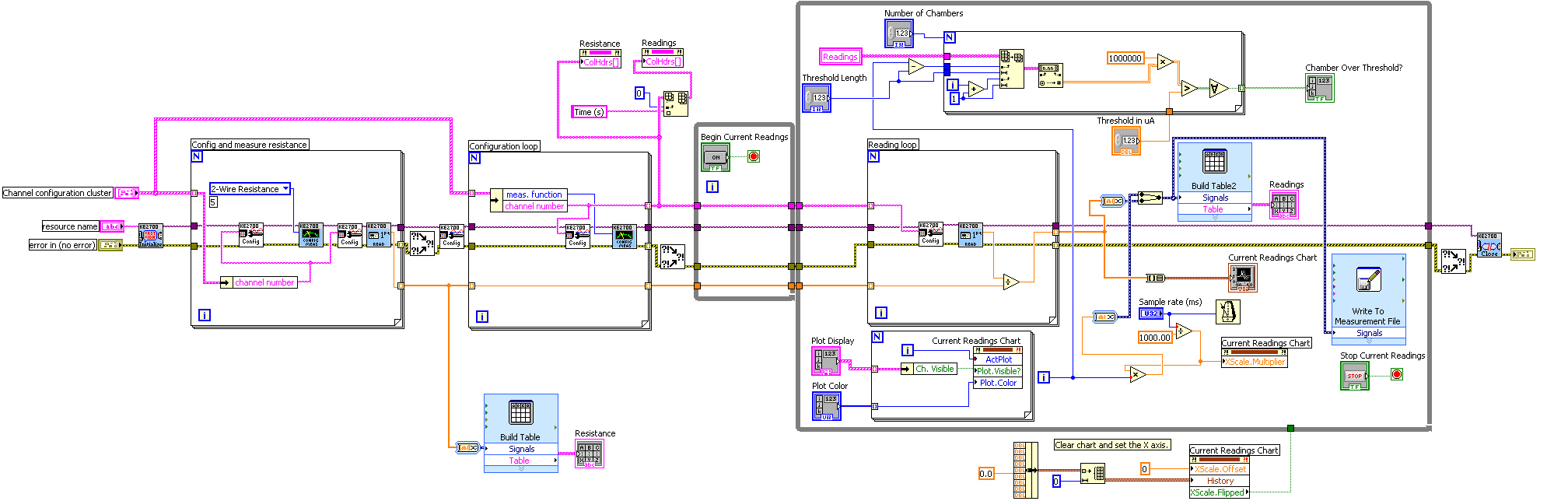

* In LabVIEW, a block diagram is used to visually write c code. Our block diagram is shown here. | * In LabVIEW, a block diagram is used to visually write c code. Our block diagram is shown here. | ||

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Labview.jpg|600px]] |

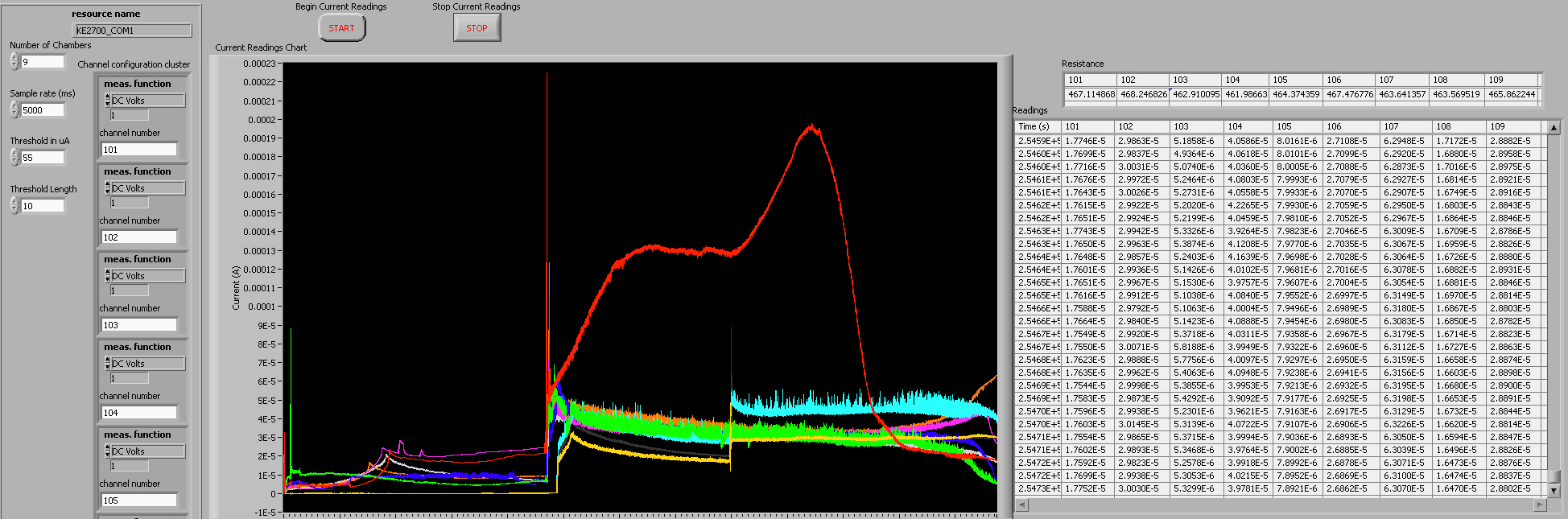

* In Labview, an instrument panel is used to allow users to specify inputs and to display the status of program variables. Our instrument panel is shown here. | * In Labview, an instrument panel is used to allow users to specify inputs and to display the status of program variables. Our instrument panel is shown here. | ||

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Labview2.jpg|600px]] |

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:12, 30 October 2008

|

|

"

"