Team:Peking University/Project

From 2008.igem.org

FeatherMount (Talk | contribs) (→The Results) |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | <div align="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/ | + | <div align="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/f/fb/Sub_page_retry.jpg" align="center" width="900" height="219" border="0" /></div> |

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | |||

{| style="color:#ba0145;background-color:#dda303;" cellpadding="3" cellspacing="1" border="1" bordercolor="#fff" width="95%" align="center" | {| style="color:#ba0145;background-color:#dda303;" cellpadding="3" cellspacing="1" border="1" bordercolor="#fff" width="95%" align="center" | ||

| Line 50: | Line 51: | ||

Inspired by this work, we hope to engineer a genetic circuit in yeast that will govern the directed evolution process from mutation to selection. Compared to human B-cells, yeast is cheap and reproduces incredibly fast. Moreover, yeast is a very well characterized eukaryotic model with many of the post-translational abilities found in human cells, allowing us to do in vivo analysis of protein function without having to extract and purify. Our system allows for a wide variety of substrates, essentially any intermolecular interaction that involves proteins. | Inspired by this work, we hope to engineer a genetic circuit in yeast that will govern the directed evolution process from mutation to selection. Compared to human B-cells, yeast is cheap and reproduces incredibly fast. Moreover, yeast is a very well characterized eukaryotic model with many of the post-translational abilities found in human cells, allowing us to do in vivo analysis of protein function without having to extract and purify. Our system allows for a wide variety of substrates, essentially any intermolecular interaction that involves proteins. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

[http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/IGEM:Peking_University/2008/Related_Papers Learn More...] | [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/IGEM:Peking_University/2008/Related_Papers Learn More...] | ||

| Line 67: | Line 65: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | + | As a proof-of-concept experiment, here we present one very simple example in yeast one hybrid: a mutated Gal4 gene is inserted in the target cassette. The selector cassette contains UAS to drive expression of His3, LacZ and LacI. All three plasmids are transfected or knock-in-ed into gal4-, his3- yeast strain with proper selection tags. Initially, we culture the yeast in complete YPD medium. Defect Gal4 product cannot bind to UAS, hence hAID-LexA is constitutively expressed, recruited to LexO sites of the target, and mutates the Gal4 conding sequence. Once Gal4 mutation is reversed, it binds to UAS to drive LacI expression, which represses hAID-LexA. We plate the yeast into Trp-, His-, Leu-, 3AT+, XGal+ plate and select for the large, blue colonies. Sequencing the colonies then gives us the activated Gal4 gene sequences. | |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 83: | Line 81: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

//Last modified: ZY 20080704 | //Last modified: ZY 20080704 | ||

| - | |||

=== The Experiments === | === The Experiments === | ||

| Line 103: | Line 100: | ||

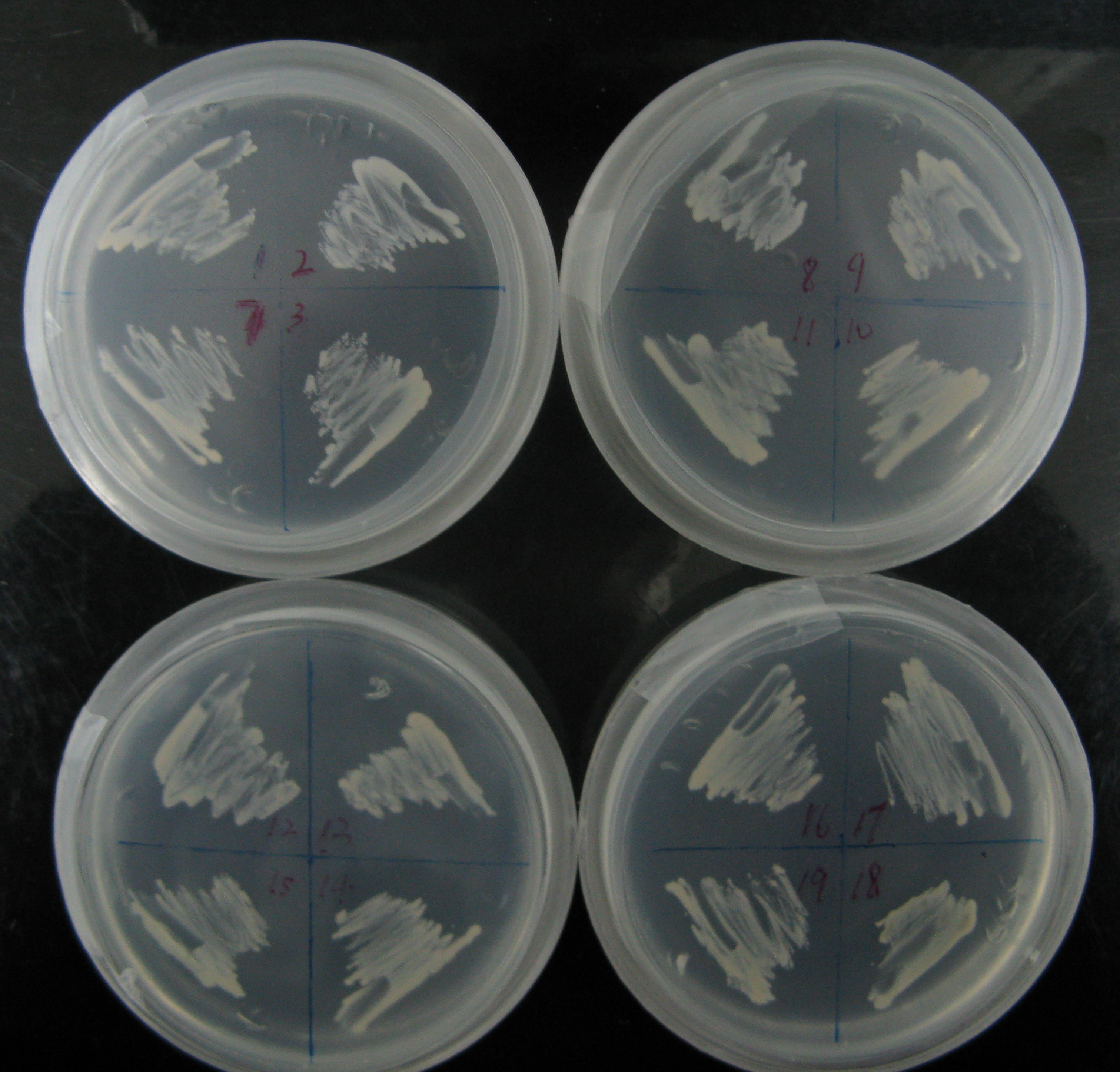

====Yeast Strains Preparation==== | ====Yeast Strains Preparation==== | ||

| - | Among more than 50 plasmids we have constructed, we have chosen the above 16 groups for the following yeast screening task. For the AID construct which is on pGREG504, we have pGREG-lacS (note: lacS is one type of pADH-lac promoters) as a negative control and those with lac1, another pADH-lac promoter. A set of four linkers were tested in order to mostly maintain the original activity of hAID. For the GAL4 constructs, many spot mutations were triggered in order to disrupt function of wildtype GAL4 but only a spot mutation at 77-position (C77T) was selected to carry out the further yeast screening process. GAL4(C77T) is not in the hot spot as predicted previously (See Modeling Part), high rate and successful muatation of this mutant to functional one will to a great extent suggest that in our system the hAID can | + | Among more than 50 plasmids we have constructed, we have chosen the above 16 groups for the following yeast screening task. For the AID construct which is on pGREG504, we have pGREG-lacS (note: lacS is one type of pADH-lac promoters) as a negative control and those with lac1, another pADH-lac promoter. A set of four linkers were tested in order to mostly maintain the original activity of hAID. For the GAL4 constructs, many spot mutations were triggered in order to disrupt function of wildtype GAL4 but only a spot mutation at 77-position (C77T) was selected to carry out the further yeast screening process. GAL4(C77T) is not in the hot spot as predicted previously (See Modeling Part), high rate and successful muatation of this mutant to functional one will to a great extent suggest that in our system the hAID can generate novel, gain-of-function mutations in the targeted gene. Wildtype ''gal4'' in pGREG505 and plasmids without ''gal4'' gene were also used as positive and negative controls. |

{| | {| | ||

| Line 110: | Line 107: | ||

As the above table listed out, 16 strains of yeast were constructed via co-transformation with AID construct and GAL4 construct. | As the above table listed out, 16 strains of yeast were constructed via co-transformation with AID construct and GAL4 construct. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Schematic Overview of Results == | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 09.jpg|700px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''Crystal structure of APO2 which is supposed to have similar structure of hAID.''' <br> | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 07.jpg|700px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''Schematic structure of hAID, showing the N-terminal as catalytic active domain and C-terminal as protein-protein interaction domain. We choosed to fuse the DNA binding domain to hAID C-terminal based on this structure-activity relationship.''' <br> | ||

| + | ''''' Jayanta Chaudhuri & Frederick W. Alt, Nature Reviews Immunology 4, 541-552 (July 2004)'''<br>'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 08.jpg|700px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''In mammalian immune cells, hAID acts in cooperation with many trans-acting factors, likely to be DNA binding protein partners in the active SHM protein complex. Our approach harnesses an alternative strategy by fusion of DNA binding domain to directly target hAID onto a specific DNA loci. '''<br> | ||

| + | '''''Valerie H. Odegard & David G. Schatz, Nature Reviews Immunology 6, 573-583 (August 2006)'''<br>'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 01.jpg|500px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''The dysfunctional Gal4(C77T) is under the control of pAct. The fusion protein hAID-lexA DBD specifically binds to the lexO region flanking the 3' of Gal4(C77T). With the facilitation of the linker, hAID is able to target to Gal4(C77T). '''<br> | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 02.jpg|500px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''The Gal4(C77T) has lost the of DNA binding activity, so it failed to induce the expression of lacI; when Gal4(C77T) is mutated until it has restored its original function, it activates the expression of lacI. '''<br> | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 03.jpg|500px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''The expression of hAID is regulated by LacI. When lacI is expressed, expression of hAID is attenuated. ''' <br> | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 04.jpg|500px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''The triad relationship between the three components of our genetic circuit.'''<br> | ||

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 05.jpg|500px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''For yeast screening process, two different reporters are used. His3 is used to report the viability of yeast strain. Functional Gal4 is able to induce the expression of His3 which enables the yeast strain to survive on the His- medium. Another reporter gene lacZ will enable us to use blue and white screening based on X-Gal plate.''' <br><br><br><br> | ||

== The Results == | == The Results == | ||

| - | [[Image:Yeast_Screening.gif]]<br> | + | [[Image:Yeast_Screening.gif]] <br> |

| - | The basic principle for our yeast screening is to test the viability of the 16 yeast strains. If our dysfunctional GAL4 is mutated to functional GAL4, this will lead to the further activation of HIS3 gene under the control of GAL1 promoter in yeast strain AH109. | + | As a proof-of-concept experiment, we firstly tested whether overexpression hAID-LexA DBD fusion protein would enhance targetted mutagenesis efficiency without LacI repressor. The basic principle for our yeast screening is to test the viability of the 16 yeast strains. If our dysfunctional GAL4 is mutated to functional GAL4, this will lead to the further activation of HIS3 gene under the control of GAL1 promoter in yeast strain AH109. We choosed to use the Gal4(C77T) mutant because it is a null mutant but not of a hotspot of traditional hAID SHM, which means additional gain-of-function novel mutation is needed to revert the phenotype. |

| - | On the first day of screening, we have observed that the GAL4(C77T) is | + | |

| + | [[Image:3 component-3 10.jpg|960px]]<br> | ||

| + | '''Detailed view of P26 region of Gal4 in a Gal4-DNA complex structure. P26 is the outmost amino acid in the turning region of Gal4 helix DNA binding domain, and is essential for maintaining the structural motif needed to form coordination bond with Zn2+ ion (the yellow particle). Further more, the five-element ring structure of this proline has critical role to stablize the structure of Zinc finger domain. Replacing the proline to leucine drastically alters the structure and nullifies DNA binding function of Gal4. This structure-based theoretical prediction is consistent with our experiment result -- yeast strains containing Gal4(C77T) but without hAID or its fusion protein failed to grow on histidine free medium. '''<br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | All strains were inoculated into liquid medium in which the concentration of histidine gradually reduced during the week’s long screening. Then, cells were plated on agar plates containing NO His to test their viability ([[Media:Yeast Screening Model Plate.JPG|See figure]]). The culturing of the yeast and the plating used the following protocols. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On the first day of screening, we have observed that the GAL4(C77T) is dysfunctional. AH109 cells transfected with UAS-Gal4(C77T) plated on the histidine free medium grew aberrantly and could not form dense lawn of cells (Fig.1A), whilst the positive control groups containing UAS-Gal4(wt), grew rapidly on histidine free medium(Fig.1B). | ||

[[Image:Figure 1.gif|400px]] | [[Image:Figure 1.gif|400px]] | ||

[[Image:Figure 2.gif|500px]]<br> | [[Image:Figure 2.gif|500px]]<br> | ||

| - | + | On the first day of screening, we did not observe our experiment groups, those strains containing the deficiency GAL4 construct and the hAID gene, survive on the histidine free plate. | |

| + | |||

| + | On the second day of screening, we had luckily found that our strains with lacS-hAID and mutant GAL4 could grow on the selective medium(Fig.2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then we want to further test the activity of the linkers between hAID and lexA DNA Binding Domain. A set of four linkers were tested using the same methods on the second day of screening. Yeast strains with linker 4, 6, 9 (See Plasmids Construction Section) show high viability than those with linker 8. This result indicates that linker length is critical in determining the hAID-linker-LexA DBD protein function, and hence implicates that DNA binding mediated by LexA DBD is crucial -- otherwise linker length would not play a role. | ||

| - | + | We continued our screening for the third day, and the experiment group as well as the negative control group both grew well on selective medium which suggests that background mutation also contributed to the evolution process. | |

| - | + | Some conclusions can be made through this round of screening. Under similar selection pressure, yeast strains with hAID-lexA DBD fusion protein evolve one day earlier than those without the mutator, suggesting a higher mutation rate in general. Specifically, the mutation rate to produce a revertant Gal4 phenotype is dependent on the linker length in between hAID and LexA DBD. This further suggests the mutagenesis efficiency of hAID-LexA DBD is dependent on LexA-mediated DNA binding. Our genetic circuits thus can increase the mutation rate of a target gene to a significant level as shown in the example of successful phenotypic reversion of GAL4(C77T). Though we have not yet been able to sequence all the mutants we obtained in the first round of screen, since C77T mutant is not within a traditional hAID SHM hotspot, it is unlikely that the mutation is a revertant. Hence, this finding suggests that the fusion protein hAID-LexA DBD enables novel gain-of-function mutagenesis in the target gene. | |

Latest revision as of 05:26, 30 October 2008

| Home | The Team | The Project | Parts | Modeling | Misc&Fun | [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/IGEM:Peking_University/2008 Our OWW] | [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/IGEM:Peking_University/2008/Notebook Notebook] |

|---|

Contents |

Project Abstract

A Genetic Circuit for Directed Evolution in vivo

Directed evolution is a powerful tool for answering scientific questions or constructing novel biological systems. Here we present a simple genetic circuit for in vivo directed evolution which comprises minimal elements for random mutation and artificial selection. We engineer yeast to generate the DNA mutator hAID, an essential protein in adaptive immunity, and target it specifically to a gene of interest. The target gene will be mutated and consequently promptly evolves. By linking the expression of hAID repressor LacI and favorite gene functionality, the mutation rate inversely correlates between the functionality of the desired gene and hAID. This circuit may be adopted for in vivo evolution in eukaryotic system on genetically encoded targets. It has a variety of potential applications in academic and industrial contexts, theoretically most inter-molecular interaction that involves proteins and RNAs.

Genetic Circuit

|

Project Background

Over millions of years, evolution has created finely tuned networks of proteins capable of producing incredible outputs because of their optimized interactions with each other. The early efforts of synthetic biologists to recreate these networks artificially has given us a new respect for just how well-optimized natural systems really are; our efforts have in general appeared clumsy next to natural examples.

However, natural evolution is a very slow process, governed by subtle selective pressures and long generation times. Therefore, scientists have developed several strategies for directed evolution in the lab, breaking it down into mutation (various PCR based techniques, shuffling, mutator strains) and selection (display technologies, etc.) These methods do cut down on time, and there have been some notable successes by researches using in-vitro directed evolution. Nevertheless, running the necessary high-throughput screens and mutagenesis protocols requires a great deal of manpower, expertise, and time.

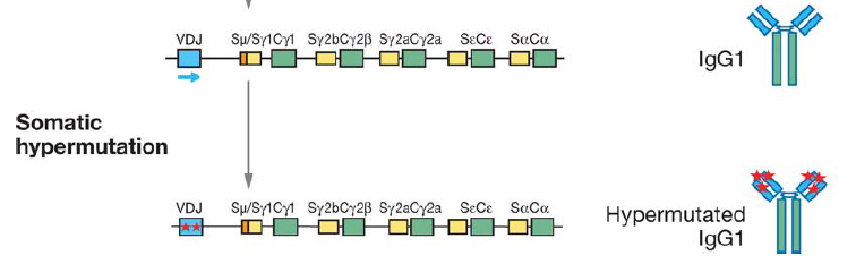

It would seem that nature has beaten us to the punch once again, however, as a natural mechanism for rapid evolution already exists: the immune system's adaptive immunity. It is well known that B-cells are capable of producing a large pool of diverse antibodies upon antigenic stimuli, a fact which underlies our own ability to survive infection. Recent work has revealed that an enzyme called AID (activation induced cytidine deaminase) is the workhorse behind this immune capacity. AID facilitates three processes crucial to antibody diversity: somatic hypermutation (SHM), class switch recombination (CSR), and gene conversion.

Briefly, AID converts cytidine to uracil by oxidizing the amino group to a carbonyl, resulting in a Watson-Crick mismatch. DNA repair pathways then are activated the remove the mismatch, resulting in a changed coding sequence of the hypervariable region that AID is targeted to. Because of its mutagenic properties, AID must be carefully targeted to avoid B-cell lymphocytoma.

AID has been shown to be functional in other cells besides human B-cells. In 2005, Youri Pavlov's group expressed human AID in yeast, and found that AID maintained a high mutation rate even in this heterologous host.

(Neuberger, M.S., et al., Somatic hypermutation at A.T pairs: polymerase error versus dUTP incorporation. Nat Rev Immunol, 2005. 5(2): p. 171-8.[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15688043?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVMedline PubMed])

Inspired by this work, we hope to engineer a genetic circuit in yeast that will govern the directed evolution process from mutation to selection. Compared to human B-cells, yeast is cheap and reproduces incredibly fast. Moreover, yeast is a very well characterized eukaryotic model with many of the post-translational abilities found in human cells, allowing us to do in vivo analysis of protein function without having to extract and purify. Our system allows for a wide variety of substrates, essentially any intermolecular interaction that involves proteins.

[http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/IGEM:Peking_University/2008/Related_Papers Learn More...]

Project Details

Project Proposal

Evolution could be dissociated into two parallel processes: random mutation, and natural selection. Whilst its role in life history is well understood and accepted, evolution is also evident across individual life process. In particular, adaptive immunity system adopts evolution strategy to produce antibodies for novel antigens. Artificial evolution method could be a powerful tool for answering scientific questions or engineering novel biological systems. Via systems biology approach, here we present a simple genetic circuit consisting functional elements for random mutation and artificial selection. This circuit may perform in vivo evolution on virtually any genetically encoded targets, with potential applications in academic and industrial contexts.

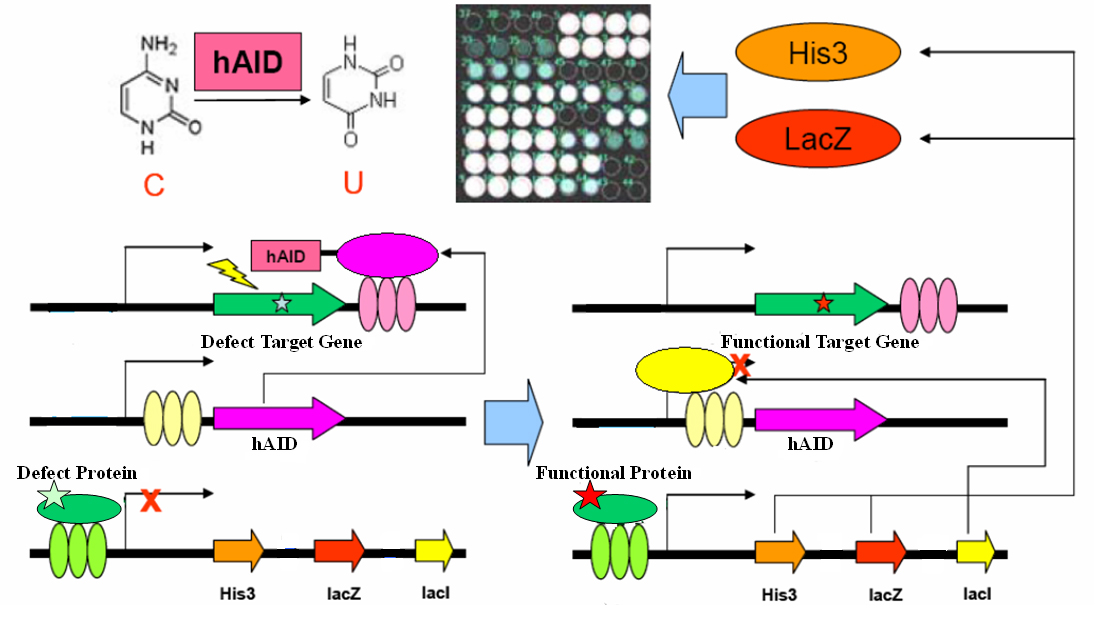

The gene encoding the core element in adaptive immunity, hAID, is fused with the LexA-DBD domain with flexible linker. The fusion gene hAID-LexA is inserted into a yeast ESC expression cassette at 3’ of tandem LacO elements. The target gene (your favorite gene, yfg) is inserted into a yeast ESC expression cassette, with its 3’UTR containing tandem LexO elements. An inducible promoter response to yfg activity drives expression of His3, LacZ and LacI in cistrone spanned by IRES. These three plasmids together form a genetic circuit for in vivo evolution.

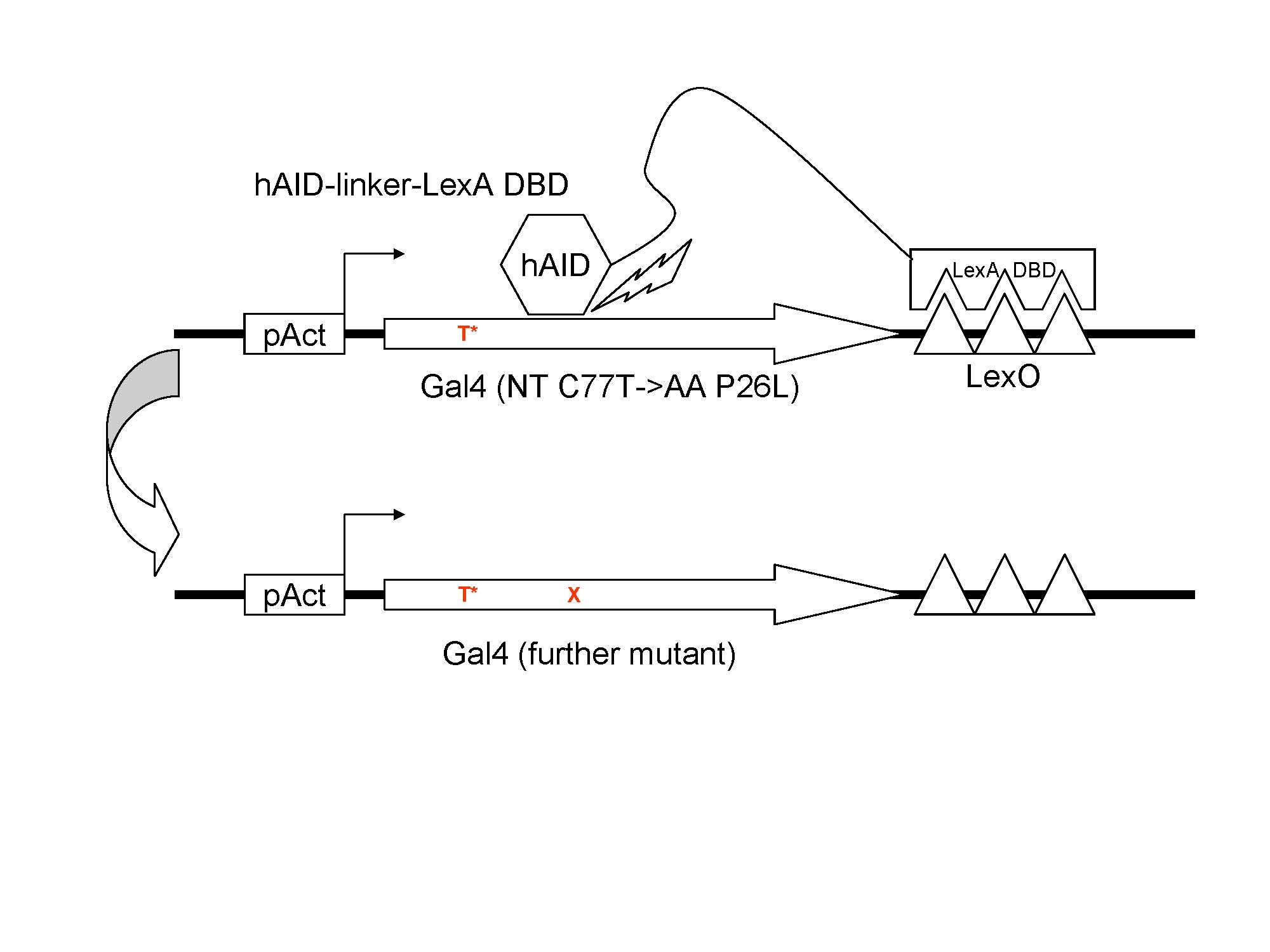

As a proof-of-concept experiment, here we present one very simple example in yeast one hybrid: a mutated Gal4 gene is inserted in the target cassette. The selector cassette contains UAS to drive expression of His3, LacZ and LacI. All three plasmids are transfected or knock-in-ed into gal4-, his3- yeast strain with proper selection tags. Initially, we culture the yeast in complete YPD medium. Defect Gal4 product cannot bind to UAS, hence hAID-LexA is constitutively expressed, recruited to LexO sites of the target, and mutates the Gal4 conding sequence. Once Gal4 mutation is reversed, it binds to UAS to drive LacI expression, which represses hAID-LexA. We plate the yeast into Trp-, His-, Leu-, 3AT+, XGal+ plate and select for the large, blue colonies. Sequencing the colonies then gives us the activated Gal4 gene sequences.

The power of this system could be best revealed in the above case: since selection is not required for initiation and attenuation of mutagenesis, there is virtually no need to perform selective pressure titration.

The system could be readily adopted to in vivo evolution of any kind of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interaction: for this we simply adopt a yeast two hybrid-like approach, evolving a functional protein linked to Gal4 AD which could bind to the "bait" protein linked to Gal4 DBD. We could also use the yeast three hybrid system to study RNA-protein interaction, or use yeast one hybrid to evolve specific protein that binds to given promotor.

Yeast shows several advantages in studying eukaryotic process, for it folds and modifies the eukaryotic protein accurately, whilst bacteria does not. Another advantage of yeast is that cell wall blocks intracellular communication between transmembrane proteins, and the selection happens completely within the cell, therefore blocking possible false positives. We plan to screen for extracellular activator of certain eukaryotic transmembrane protein, for example, novel peptidergic ligand for GPCR and antibody-antigen interaction.

We have been working on further improvements of the mutation system, by improving the enzyme to archieve directed, "hotspot-less", and evenly distributed mutagenesis, by utilizing the overwhelming power of yeast genetics, and by harnessing novel protein chemistry.

//Last modified: ZY 20080704

The Experiments

Plasmids Construction

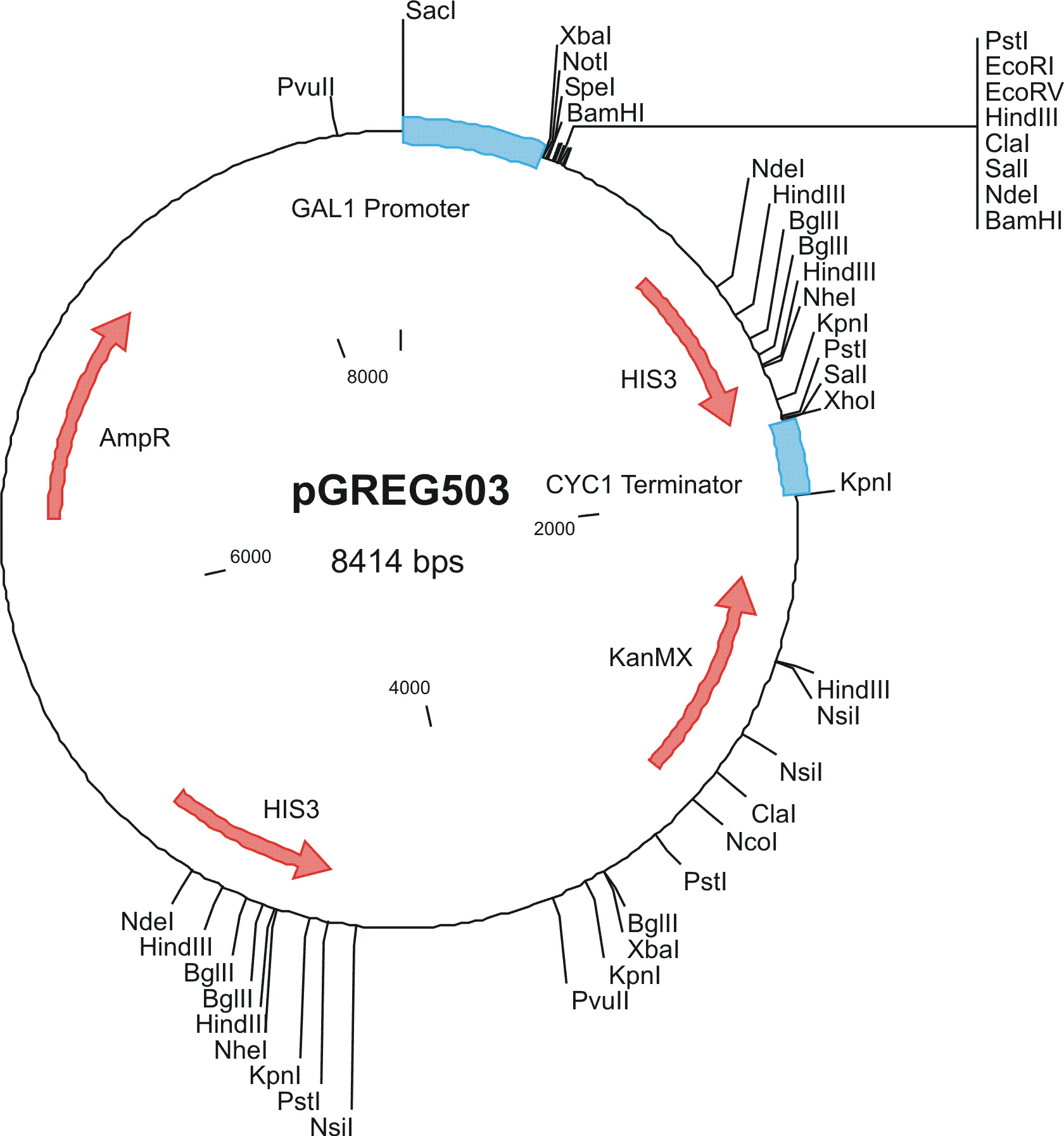

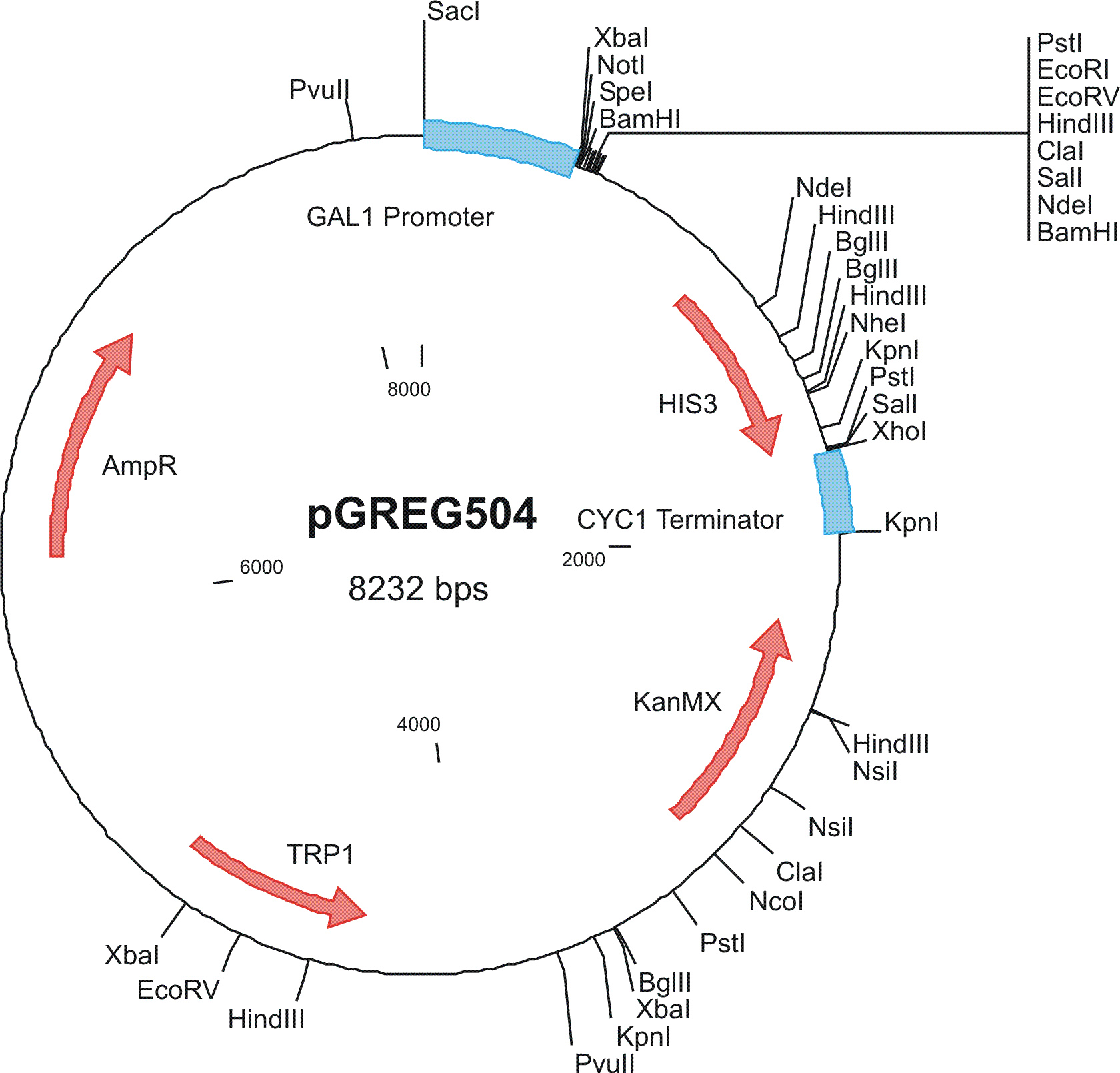

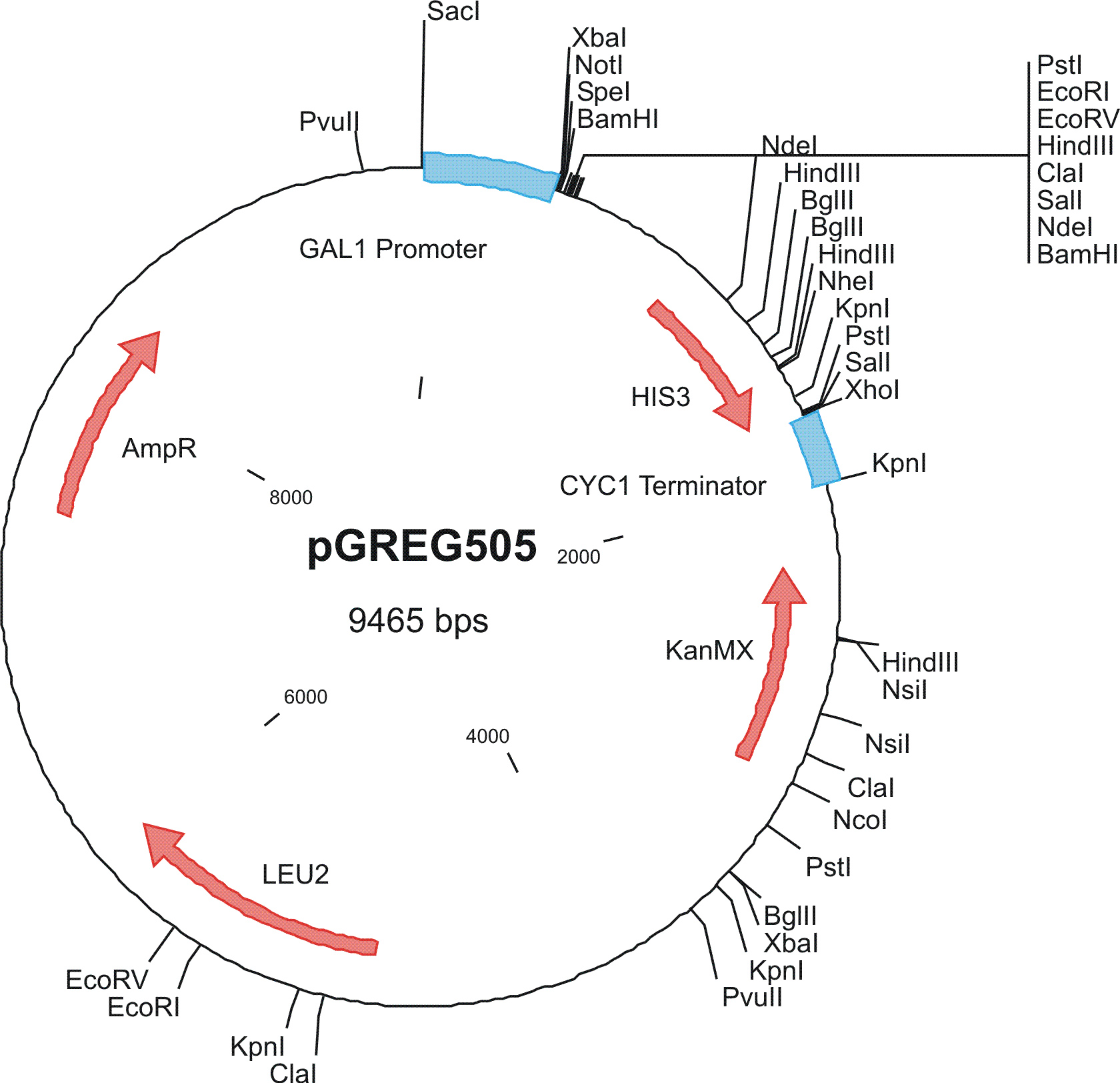

To construct the genetic circuits above, we have used the pGREG series of vectors which were hosted in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109. pGREG503, the expression plasmid with HIS3 auxotroph resistance was used to construct the UAS-lacI component. LacI was under the galactose inducible promoter GAL1. The promoters of pGREG504 and pGREG505 were replaced by pADH-lac and pACT respectively. pADH-lac is pADH based promoter which is sensitive to lacI, genes under this promoter will be inhibited by lacI. pACT is a constitutively expressing promoter derived from the promoter of actin in budding yeast. The construct hAID-linkers-lexA was under the pADH-lac promoter and the GAL4-lexO construct was engineered under the pACT promoter. Notably, our hAID sequence was yeast codon optimized kindly offered by Prof. Youri I Pavlov. A set of 12 linkers were synthesized to test the ability to maintain the activity of hAID and lexA DNA binding domain. Moreover, in the genome of the yeast strain AH109, it has GAL1-HIS3 and GAL1-lacZ constructs. PGREG504-hAID-linkers-lexA DBD was constructed via the following Figure.

|

|

|

To construct plasmid on pGREG503, we have used the versatile PCR-based homologous recombination system: the PCR product of lacI was directly co-transformed with pGREG503 and it was automatically recombined to the site flanking the 3’ of the promoter. Other constructs were accomplished with standard protocols. //Written by Zhou Zhou

Yeast Strains Preparation

Among more than 50 plasmids we have constructed, we have chosen the above 16 groups for the following yeast screening task. For the AID construct which is on pGREG504, we have pGREG-lacS (note: lacS is one type of pADH-lac promoters) as a negative control and those with lac1, another pADH-lac promoter. A set of four linkers were tested in order to mostly maintain the original activity of hAID. For the GAL4 constructs, many spot mutations were triggered in order to disrupt function of wildtype GAL4 but only a spot mutation at 77-position (C77T) was selected to carry out the further yeast screening process. GAL4(C77T) is not in the hot spot as predicted previously (See Modeling Part), high rate and successful muatation of this mutant to functional one will to a great extent suggest that in our system the hAID can generate novel, gain-of-function mutations in the targeted gene. Wildtype gal4 in pGREG505 and plasmids without gal4 gene were also used as positive and negative controls.

As the above table listed out, 16 strains of yeast were constructed via co-transformation with AID construct and GAL4 construct.

Schematic Overview of Results

Crystal structure of APO2 which is supposed to have similar structure of hAID.

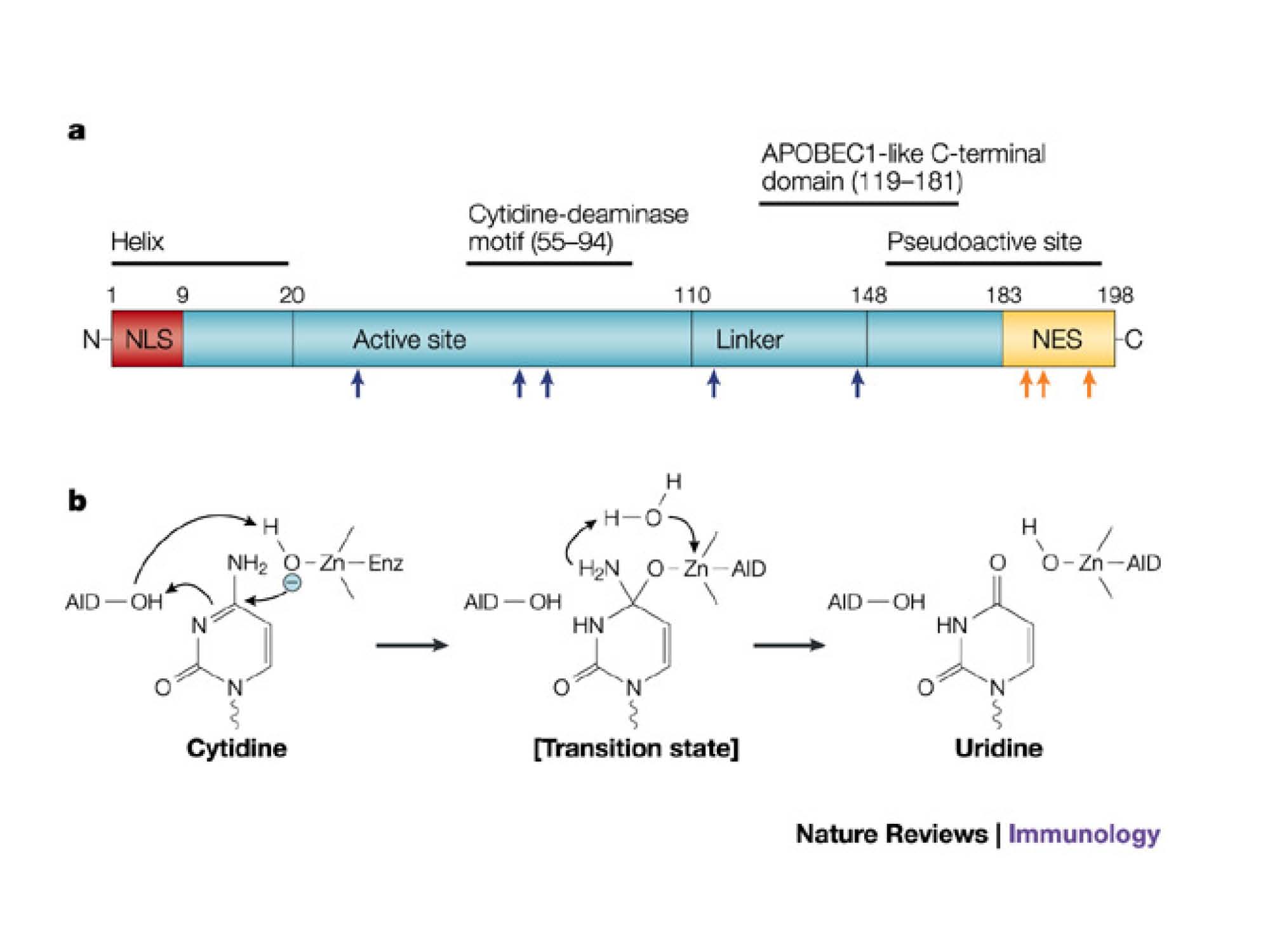

Schematic structure of hAID, showing the N-terminal as catalytic active domain and C-terminal as protein-protein interaction domain. We choosed to fuse the DNA binding domain to hAID C-terminal based on this structure-activity relationship.

Jayanta Chaudhuri & Frederick W. Alt, Nature Reviews Immunology 4, 541-552 (July 2004)

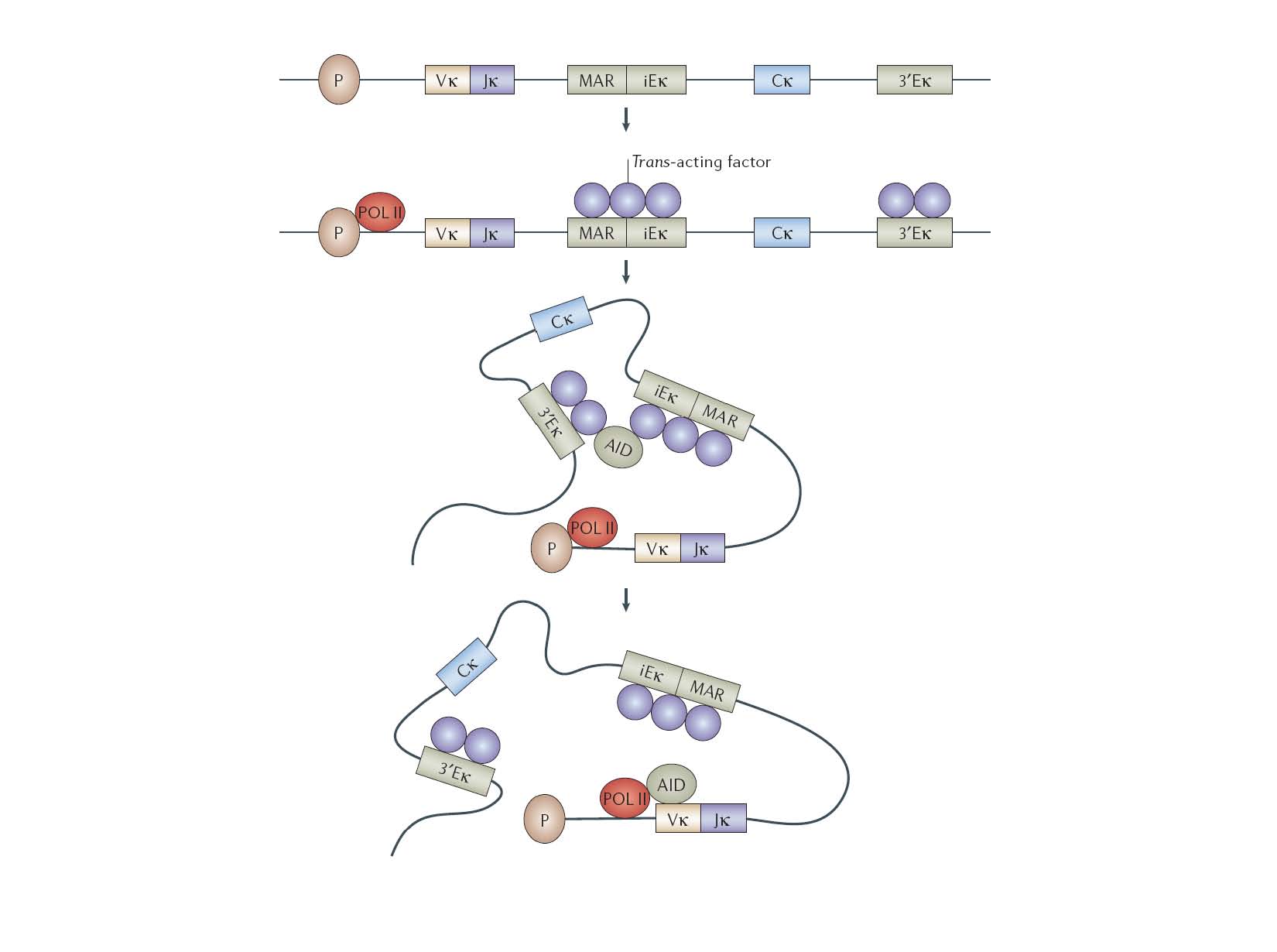

In mammalian immune cells, hAID acts in cooperation with many trans-acting factors, likely to be DNA binding protein partners in the active SHM protein complex. Our approach harnesses an alternative strategy by fusion of DNA binding domain to directly target hAID onto a specific DNA loci.

Valerie H. Odegard & David G. Schatz, Nature Reviews Immunology 6, 573-583 (August 2006)

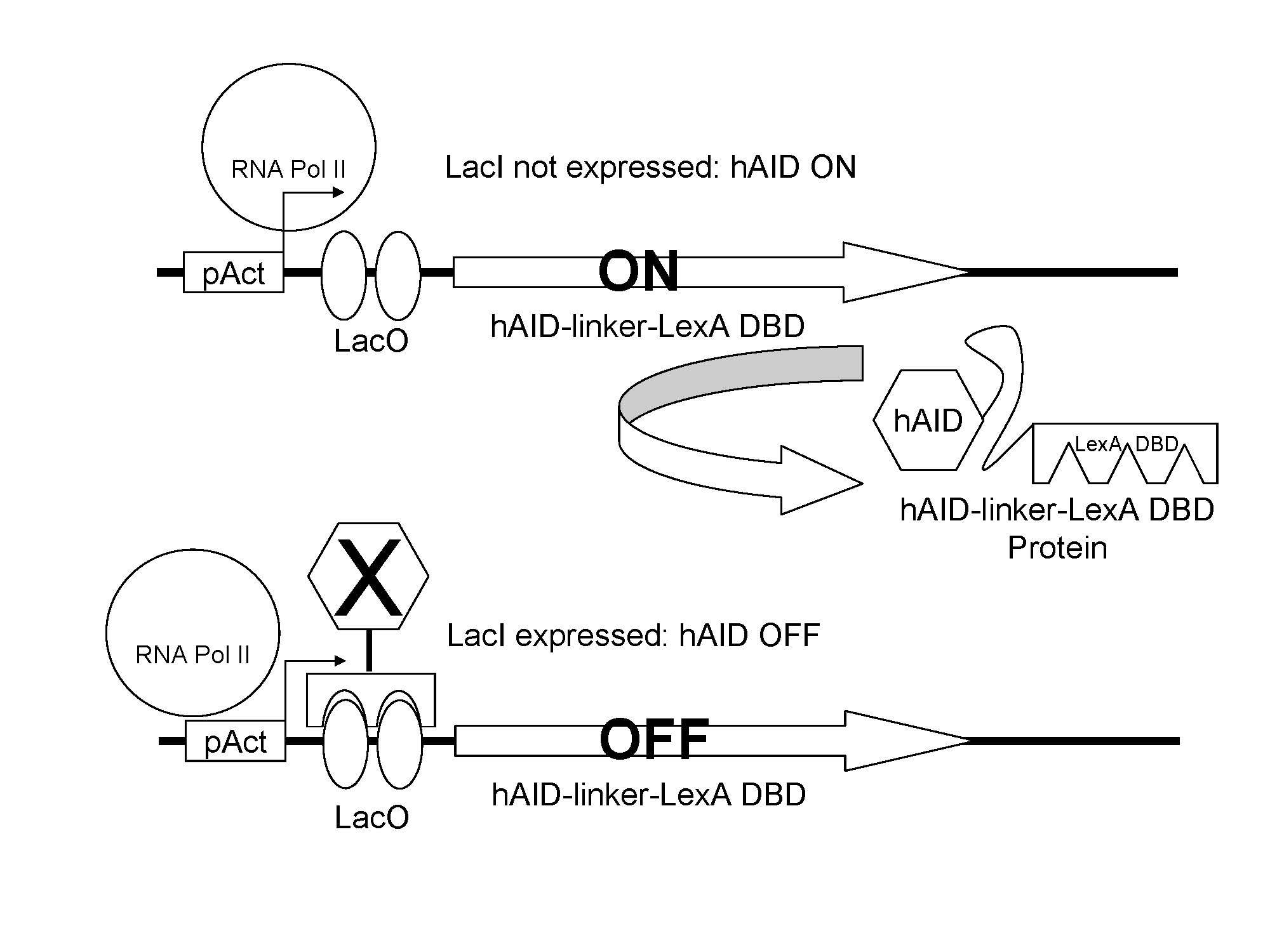

The dysfunctional Gal4(C77T) is under the control of pAct. The fusion protein hAID-lexA DBD specifically binds to the lexO region flanking the 3' of Gal4(C77T). With the facilitation of the linker, hAID is able to target to Gal4(C77T).

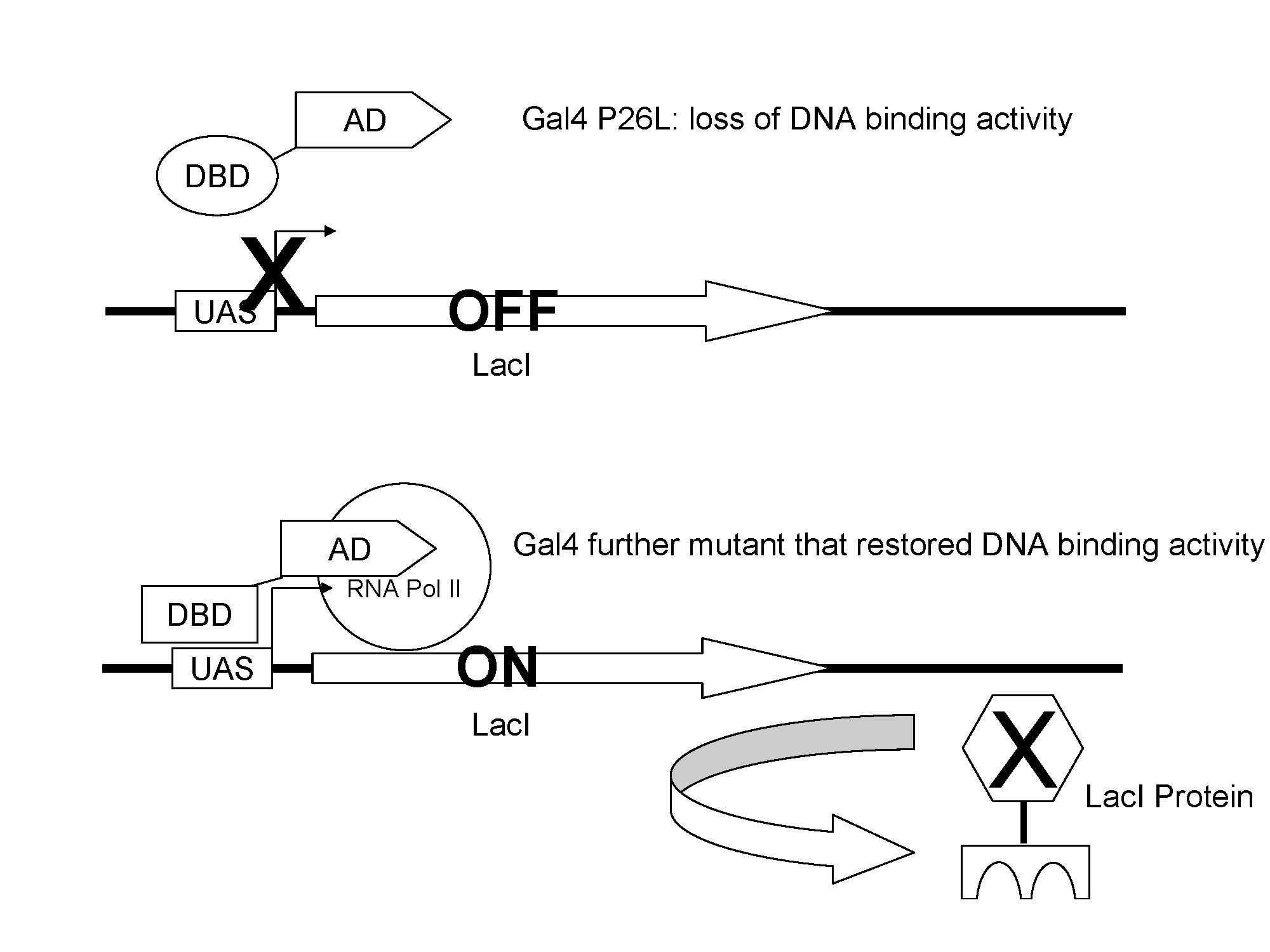

The Gal4(C77T) has lost the of DNA binding activity, so it failed to induce the expression of lacI; when Gal4(C77T) is mutated until it has restored its original function, it activates the expression of lacI.

The expression of hAID is regulated by LacI. When lacI is expressed, expression of hAID is attenuated.

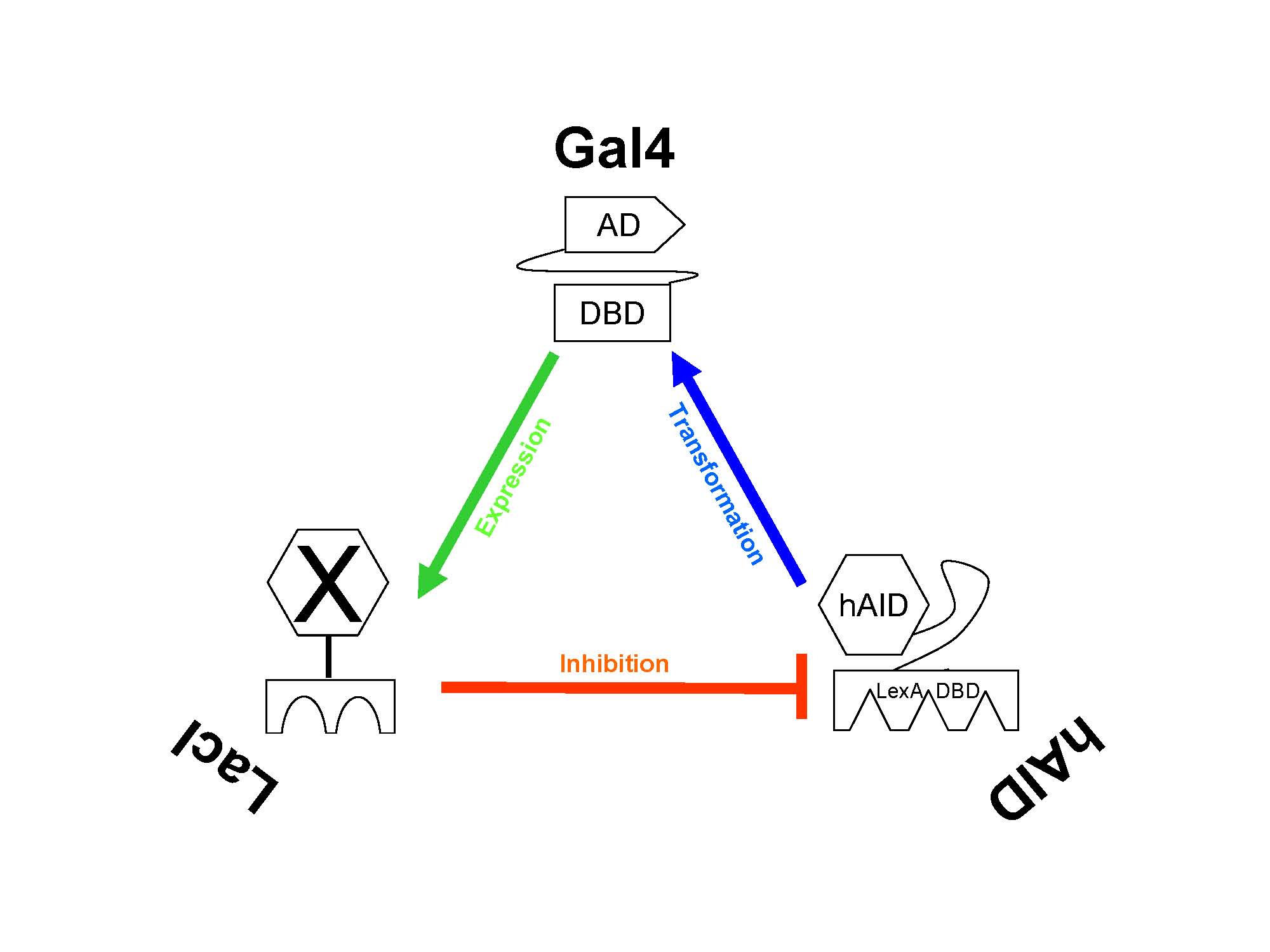

The triad relationship between the three components of our genetic circuit.

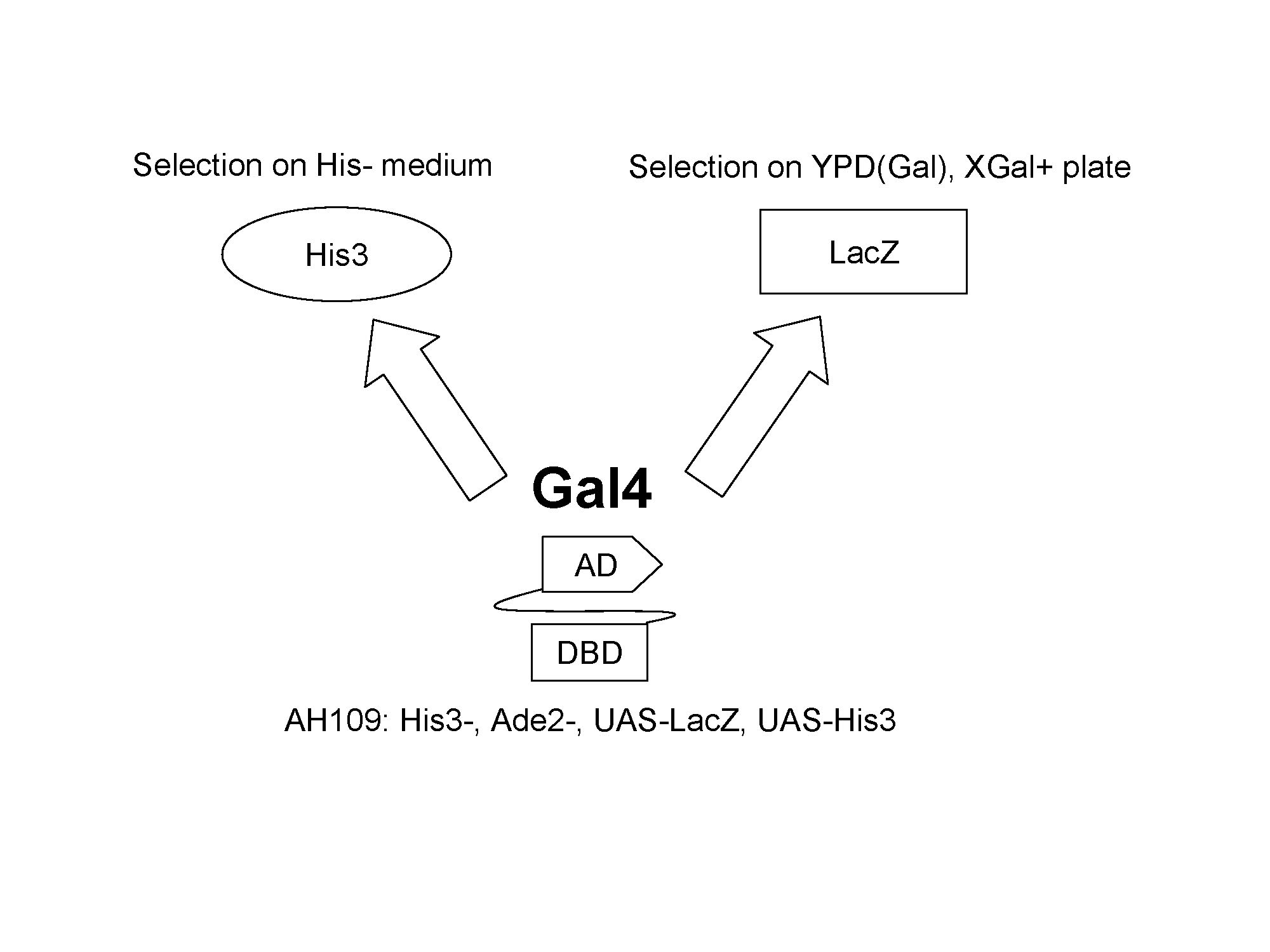

For yeast screening process, two different reporters are used. His3 is used to report the viability of yeast strain. Functional Gal4 is able to induce the expression of His3 which enables the yeast strain to survive on the His- medium. Another reporter gene lacZ will enable us to use blue and white screening based on X-Gal plate.

The Results

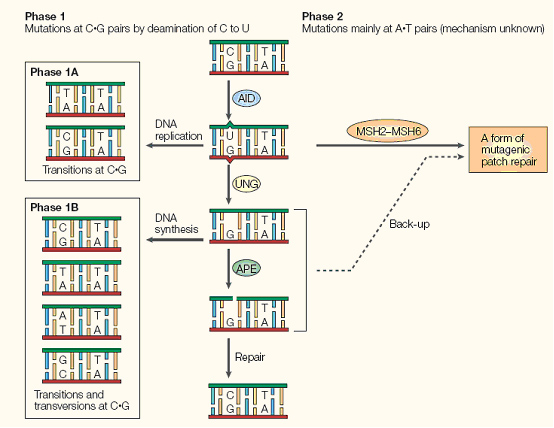

As a proof-of-concept experiment, we firstly tested whether overexpression hAID-LexA DBD fusion protein would enhance targetted mutagenesis efficiency without LacI repressor. The basic principle for our yeast screening is to test the viability of the 16 yeast strains. If our dysfunctional GAL4 is mutated to functional GAL4, this will lead to the further activation of HIS3 gene under the control of GAL1 promoter in yeast strain AH109. We choosed to use the Gal4(C77T) mutant because it is a null mutant but not of a hotspot of traditional hAID SHM, which means additional gain-of-function novel mutation is needed to revert the phenotype.

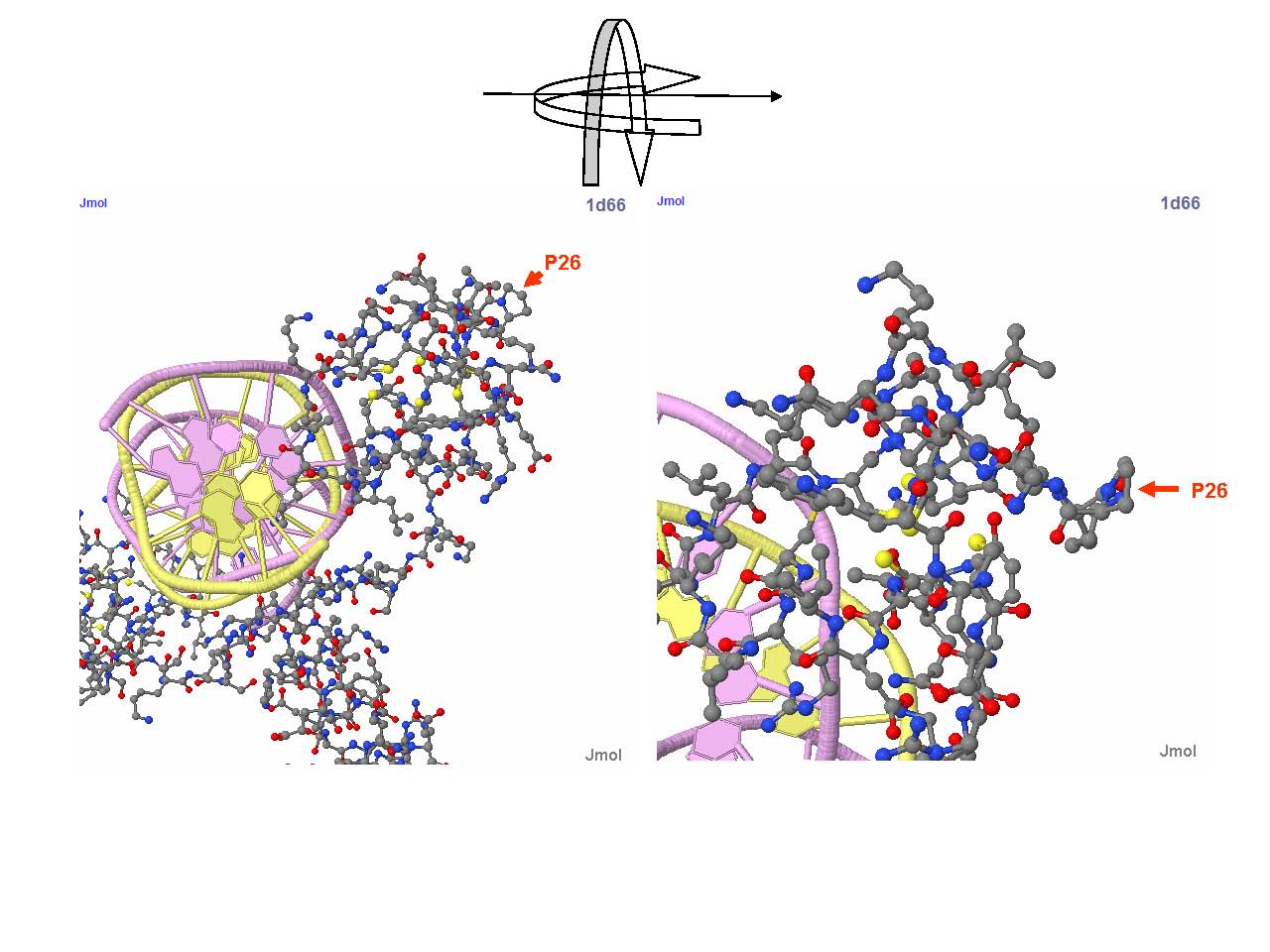

Detailed view of P26 region of Gal4 in a Gal4-DNA complex structure. P26 is the outmost amino acid in the turning region of Gal4 helix DNA binding domain, and is essential for maintaining the structural motif needed to form coordination bond with Zn2+ ion (the yellow particle). Further more, the five-element ring structure of this proline has critical role to stablize the structure of Zinc finger domain. Replacing the proline to leucine drastically alters the structure and nullifies DNA binding function of Gal4. This structure-based theoretical prediction is consistent with our experiment result -- yeast strains containing Gal4(C77T) but without hAID or its fusion protein failed to grow on histidine free medium.

All strains were inoculated into liquid medium in which the concentration of histidine gradually reduced during the week’s long screening. Then, cells were plated on agar plates containing NO His to test their viability (See figure). The culturing of the yeast and the plating used the following protocols.

On the first day of screening, we have observed that the GAL4(C77T) is dysfunctional. AH109 cells transfected with UAS-Gal4(C77T) plated on the histidine free medium grew aberrantly and could not form dense lawn of cells (Fig.1A), whilst the positive control groups containing UAS-Gal4(wt), grew rapidly on histidine free medium(Fig.1B).

On the first day of screening, we did not observe our experiment groups, those strains containing the deficiency GAL4 construct and the hAID gene, survive on the histidine free plate.

On the second day of screening, we had luckily found that our strains with lacS-hAID and mutant GAL4 could grow on the selective medium(Fig.2).

Then we want to further test the activity of the linkers between hAID and lexA DNA Binding Domain. A set of four linkers were tested using the same methods on the second day of screening. Yeast strains with linker 4, 6, 9 (See Plasmids Construction Section) show high viability than those with linker 8. This result indicates that linker length is critical in determining the hAID-linker-LexA DBD protein function, and hence implicates that DNA binding mediated by LexA DBD is crucial -- otherwise linker length would not play a role.

We continued our screening for the third day, and the experiment group as well as the negative control group both grew well on selective medium which suggests that background mutation also contributed to the evolution process.

Some conclusions can be made through this round of screening. Under similar selection pressure, yeast strains with hAID-lexA DBD fusion protein evolve one day earlier than those without the mutator, suggesting a higher mutation rate in general. Specifically, the mutation rate to produce a revertant Gal4 phenotype is dependent on the linker length in between hAID and LexA DBD. This further suggests the mutagenesis efficiency of hAID-LexA DBD is dependent on LexA-mediated DNA binding. Our genetic circuits thus can increase the mutation rate of a target gene to a significant level as shown in the example of successful phenotypic reversion of GAL4(C77T). Though we have not yet been able to sequence all the mutants we obtained in the first round of screen, since C77T mutant is not within a traditional hAID SHM hotspot, it is unlikely that the mutation is a revertant. Hence, this finding suggests that the fusion protein hAID-LexA DBD enables novel gain-of-function mutagenesis in the target gene.

"

"