Team:BrownTwo/Implementation/syntf

From 2008.igem.org

(→Synthetic transcription factors) |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

| - | [[image:Transcription_factor.png|thumb|center|550px|An example of a synthetic transcription factor, driven by the pGAL1 promoter and followed by a terminator]] | + | [[image:Transcription_factor.png|thumb|center|550px|An example of a synthetic transcription factor, driven by the pGAL1 promoter and followed by a terminator (Ajo-Frankling et al., 2007]] |

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

While our device was built to function solely on the level of transcription, one can easily imagine the opportunity for other modes of regulation. Our repressor for the gene of interest in the model can be replaced with a gene encoding for shRNA that targets the mRNA of gene G. In this case, our limiter would be tuned to interfere with translation. Alternatively, the repressor could be in the form of a protein that is not a transcription factor. Rather, this repressor protein could be designed to target the gene product of G, thus blocking its activity, or even the activator A by inhibiting its regulatory effects on gene G. Such regulation would thus occur on the level of protein-protein interactions. Along this train of thought, it is even possible to devise regulatory systems that affect gene G on multiple levels for enhanced regulation. | While our device was built to function solely on the level of transcription, one can easily imagine the opportunity for other modes of regulation. Our repressor for the gene of interest in the model can be replaced with a gene encoding for shRNA that targets the mRNA of gene G. In this case, our limiter would be tuned to interfere with translation. Alternatively, the repressor could be in the form of a protein that is not a transcription factor. Rather, this repressor protein could be designed to target the gene product of G, thus blocking its activity, or even the activator A by inhibiting its regulatory effects on gene G. Such regulation would thus occur on the level of protein-protein interactions. Along this train of thought, it is even possible to devise regulatory systems that affect gene G on multiple levels for enhanced regulation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =References= | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. Caroline M. Ajo-Franklin et al. Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. ''Genes & Dev.'' 2007 21: 2271-2276 | ||

Revision as of 03:20, 30 October 2008

|

The design of our limiter incorporates multiple transcription factors, each binding specifically to certain promoters, often in combination with others. To achieve this precise orchestration of our control elements, we employ a synthetic system of transcription factors, each binding to a distinct operator site which can be combined to create an enormous variety of transcriptional control

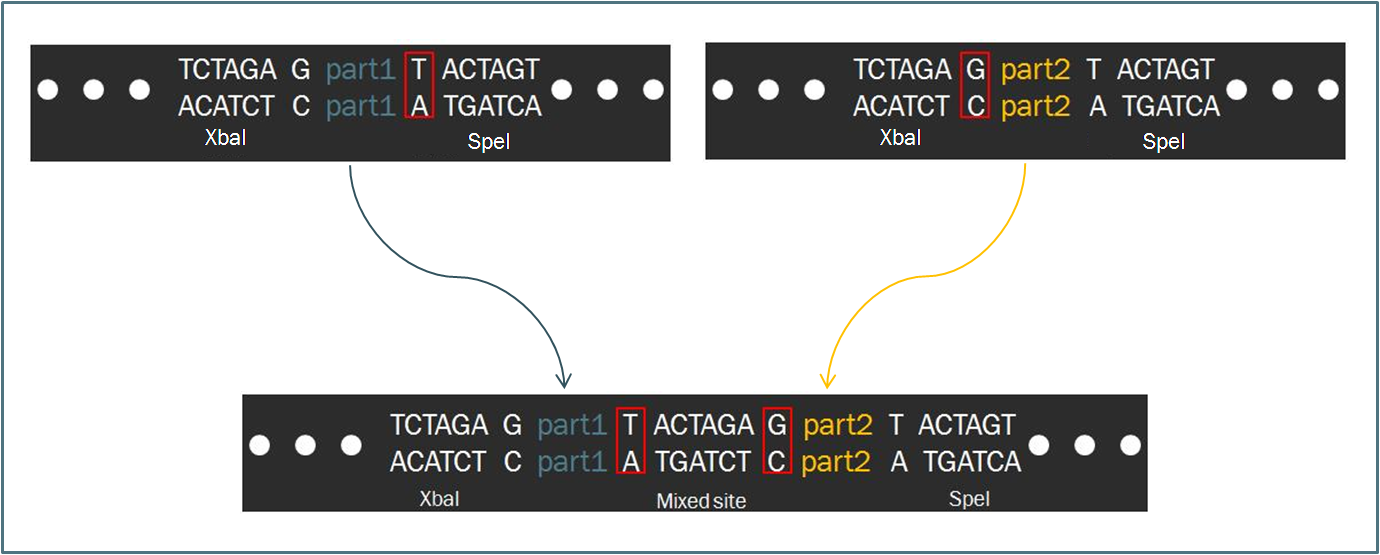

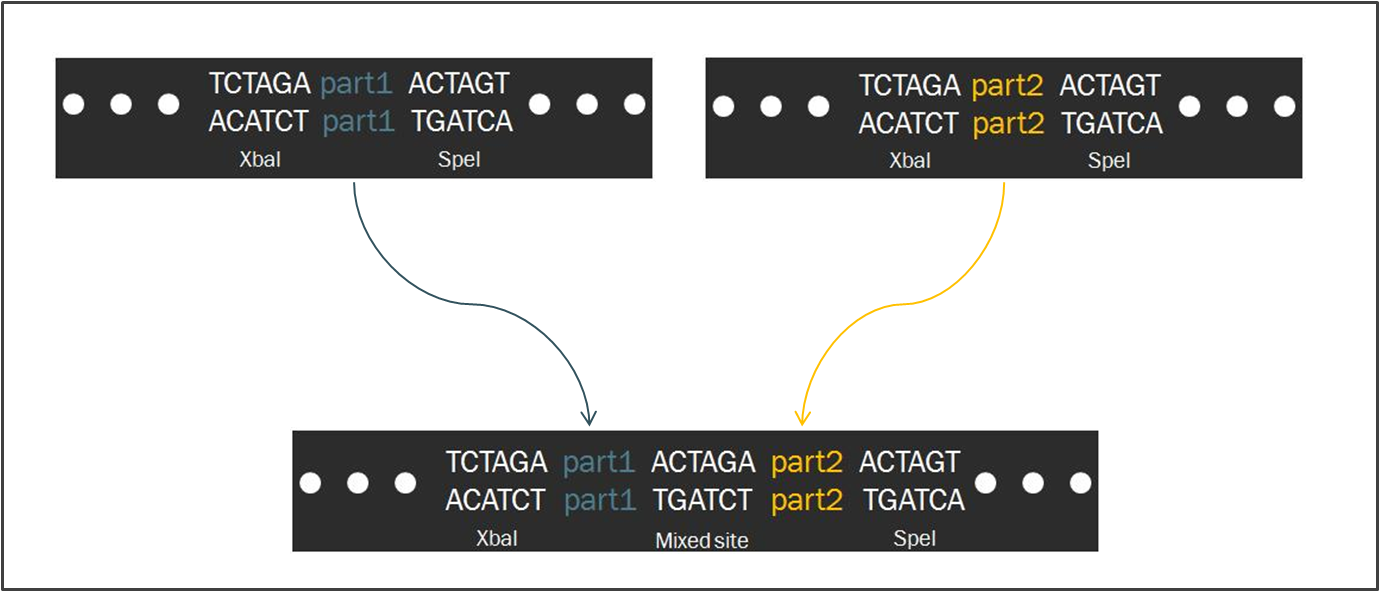

The Power of Standardized ModularityTo make the engineering of biology easier, synthetic biologists devote considerable attention towards the standardization of parts and of practice. The inspiration for such a focus stems from similar concepts in engineering, which depends upon well-characterized components for the design of complex systems with predictable and reliable behavior. As such, the iGEM competition makes use of the Biobrick standard, an idempotent approach to cloning recombinant DNA. The Biobrick standard constitutes a conserved sequence of four restriction enzyme cut sites that envelop a genetic part, whether it be a coding gene, a promoter, or some other functional piece of DNA. According to the process of Standard Assembly, one can then ligate two such parts together after following a formulaic scheme of restriction digest reactions. The end result is a linking of two two genetic parts bounded by the same four restriction sites in a reproducible fashion. Such a system facilitates the pairing of two parts, allowing for the creation of endless combinations while constructing a device.

Intrinsic to the Biobrick standard is the placement of a single nucleotide between the part and each of its adjacent restriction sites, namely XbaI and SpeI. The nucleotides are intended to act as spacers to protect the part from enzyme cleavage. When two Biobrick parts are ligated together according to the Standard Assembly, exactly one spacer nucleotide from each Biobrick is maintained in the composite part. The result is a total of eight nucleotides that lie between the two parts, comprised of these two spacers plus the hybrid XbaI/SpeI site.

The difference in separation length between two DNA parts is significant with respect to translation. During protein synthesis, ribosomes recognize groups of three consecutive nucleotides known as codons and translate each codon into a particular amino acid. Should an additional nucleotide appear in the mRNA sequence, the the grouping of nucleotides into threes will be shifted, resulting in an entirely new and undesired sequence of amino acids.

Therefore, since the length of the sequence separating two Biobrick parts is not divisible by three, a frame shift occurs. If the second Biobrick happens to be a protein-coding sequence of DNA, it will not be translated correctly. Biofusion improves upon these constraints, enabling a synthetic biologist to append numerous protein-coding regions to one another.

By nature of their design, both Biobrick and Biofusion parts can be utilized in the design of modular devices. However, the Biofusion standard provides for even greater customization by allowing for the creation of fusion proteins, hybrid proteins formed by the fusion of protein domains to one another to generate a single functional protein with characteristics from its constitutive parts.

This modular scheme for protein design lies at the heart of our limiter device. Synthetic transcription factorsExcluding the case of our proof-of-principle design, our limiter device is composed entirely of synthetic transcription factors created according to the Biofusion standard. As described in Ajo-Franklin et al., Genes & Dev. 2007 21: 2271-2276, the laboratory of Dr. Pamela Silver at Harvard developed these synthetic transcription factors for the construction of a novel “memory device” in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. While the details of this device are not essential to understanding our own gene network, it is important to discuss the significance of these transcription factors to our design.

More so than the activation and repression domains, the binding domains define the ability to construct a complex synthetic network. It is possible to define which transcription factors act upon a given promoter simply by appending one of the short binding sites to that promoter. Conversely, one can select a promoter for a given transcription factor to affect by modifying the binding domain on the protein. This latter point describes an essential component of our limiter network, which aims to target an endogenous promoter. In theory, as long as the binding domain of any transcription factor for an endogenous promoter is known, it should be possible to create a synthetic transcription factor to act on that promoter. The Biofusion standard affords for considerable flexibility in this regard. Other parts of these synthetic transcription factors include a dimer of fluorescent tags and an SV40 nuclear localization sequence (NLS). We currently have three versions fluorescence: mCherryx2, YFPx2, and CFPx2. Note that all three of these fluorescent domains have been codon-optimized for yeast expression. The inherent fluorescence built into these transcription factors allows for a steady-state and even dynamic read-out of expression levels of the transcription factors. Furthermore, the double fluorescent tags provide an enhanced stability to the protein. Finally, the nuclear localization sequence, as the name implies, targets each transcription factor back into the yeast nucleus after translation, allowing the protein to regulate transcription. Other schemes of regulationWhile our device was built to function solely on the level of transcription, one can easily imagine the opportunity for other modes of regulation. Our repressor for the gene of interest in the model can be replaced with a gene encoding for shRNA that targets the mRNA of gene G. In this case, our limiter would be tuned to interfere with translation. Alternatively, the repressor could be in the form of a protein that is not a transcription factor. Rather, this repressor protein could be designed to target the gene product of G, thus blocking its activity, or even the activator A by inhibiting its regulatory effects on gene G. Such regulation would thus occur on the level of protein-protein interactions. Along this train of thought, it is even possible to devise regulatory systems that affect gene G on multiple levels for enhanced regulation. References1. Caroline M. Ajo-Franklin et al. Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. Genes & Dev. 2007 21: 2271-2276 |

"

"