Team:Edinburgh/Plan/Cellulolysis

From 2008.igem.org

(→Cellulases) |

(→Cellulases) |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

* [https://2008.igem.org/Team:Edinburgh/cex '''''cex'''''] (exoglucanase) from ''C. fimi'' | * [https://2008.igem.org/Team:Edinburgh/cex '''''cex'''''] (exoglucanase) from ''C. fimi'' | ||

* [https://2008.igem.org/Team:Edinburgh/bglX '''''bglX'''''] (β-glucosidase) from ''Cytophaga hutchinsonii'', a member of Bacteroidetes | * [https://2008.igem.org/Team:Edinburgh/bglX '''''bglX'''''] (β-glucosidase) from ''Cytophaga hutchinsonii'', a member of Bacteroidetes | ||

| + | |||

| + | The genome sequence of ''C. hutchinsonii'' is available. We have prepared genomic DNA for ''C. fimi'' and submitted it to the School of Biological Sciences Sequencing Facility for de novo genome sequencing using the Solexa instrument, so that we can look for other cellulase genes in this organism, but unfortunately the queue is so long that we will not have any useful results before the Jamboree. | ||

=== A glucose-repressible promoter === | === A glucose-repressible promoter === | ||

Revision as of 20:18, 29 October 2008

Contents |

Cellulolysis

Cellulases must be synthesised and must be released into the growth medium, where they can digest cellulose into starch.

Genes

Cellulases

In order to digest cellulose into glucose 3 enzymes are needed: an endoglucanase (which nicks the long polysaccharide chains in cellulose), an exoglucanase (which releases cellobiose from the chain ends exposed by endoglucanase activity), and a β-glucosidase, to convert cellobiose to D-glucose.

We decided on the following genes (click the names for further information):

- cenA (endoglucanse) from Cellulomonas fimi, a member of the Actinobacteria

- cex (exoglucanase) from C. fimi

- bglX (β-glucosidase) from Cytophaga hutchinsonii, a member of Bacteroidetes

The genome sequence of C. hutchinsonii is available. We have prepared genomic DNA for C. fimi and submitted it to the School of Biological Sciences Sequencing Facility for de novo genome sequencing using the Solexa instrument, so that we can look for other cellulase genes in this organism, but unfortunately the queue is so long that we will not have any useful results before the Jamboree.

A glucose-repressible promoter

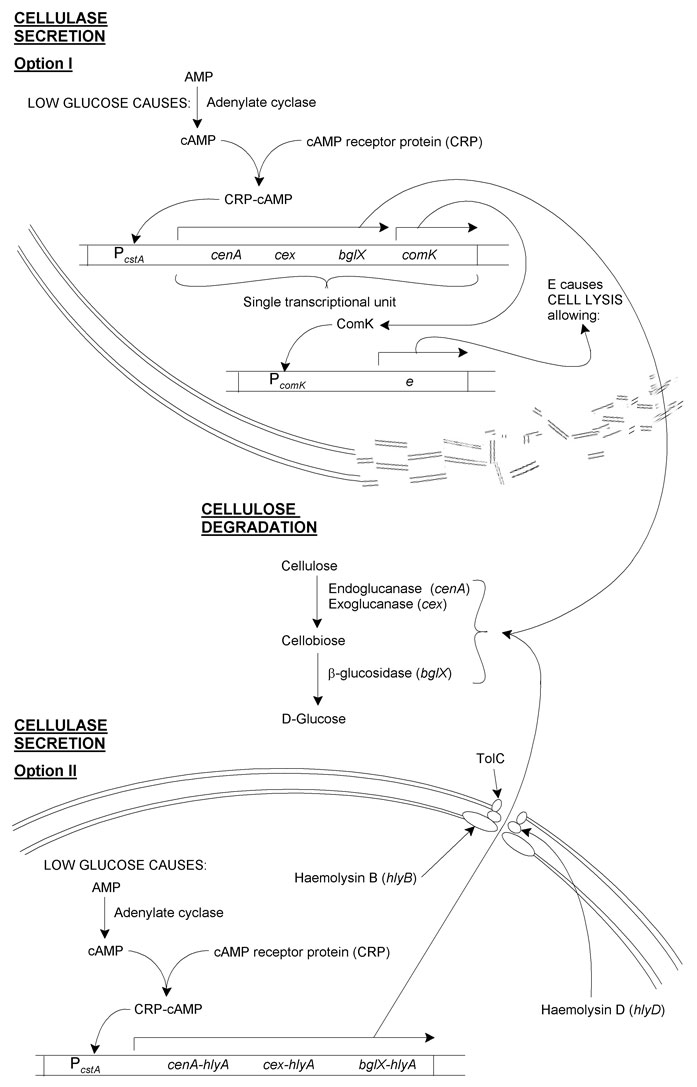

cenA, cex and bglX should be expressed as an operon under the control of PcstA. This is a glucose-sensitive promoter controlled by the cAMP receptor protein (CRP). (To summarise: low glucose concentration is detected by adenylate cyclase, which increases its activity converting AMP to cAMP. cAMP associates with CRP, and this cAMP-CRP complex associates with the glucose-sensitive promoter, in our case PcstA.)

A glucose-sensitive promoter seemed appropriate because it gives feedback to the system, whereby less of the downstream product of cellulysis (glucose) will leads to the production of enzymes which will ultimately lead to the creation of more glucose.

We decided on PcstA, because this has one of only a handful of glucose-sensitive operators to specifically bind CRP (i.e. no other transcription factors are known associate with it), so is easy to test. What's more, it is a rare example of a BioBrickTM promoter that can be turned off with the addition of a small molecule rather than being turned on by one.

Cellulase secretion

E. coli JM109 is not endowed with the type II secretory system (Main Terminal Branch of the General Secretory Pathway), and as such does not naturally secrete proteins. This left us with the problem of how to get our cellulase proteins from the bacterial cytoplasm into growth medium. We decided to design and model two systems to overcome this.

I. Induced cell lysis

This method involves having cells lyse after cellulases are produced, causing the release of these cellulases:

In addition to the cellulases, comK, a B. subtilis self-acting transcriptional activator would be placed at the end of the operon. This would then act on PcomK, which would be used as a promoter for e from phage φX174. E is a short peptide that causes E. coli cell lysis.

Thus, cellulases are made by cells in regions of local glucose depletion. Along with these is ComK. ComK then causes synthesis of E, resulting in lysis and the release of the cellulases into the medium. The cellulases then convert cellulose to glucose, increasing the local concentration of glucose for uptake by non-lysed cells.

At first glance it may seem superfluous to have production of ComK and E under the control of PcomK. (Why not just have e as part of the cellulase operon?) There are several reasons for this:

- Efficiency at each step is likely to be less than 100%, a culmination in the steps involved will reduce the efficiency as a product of the efficiency of each step. This will allow more cellulases to be produced prior to lysis.

- Using multiple steps also increases the time available for cellulase synthesis, again resulting in greater cellulase production.

- Having e under the control of a transgenic promoter should result in a lower basal level of transcription, something that we want to minimise. - Of course, this means that if the system were transferred to B. subtilis at a later stage, comK and PcomK would have to be changed.

II. An engineered α-haemolysin secretion system

As there may be some problem either with spontaneous or insufficient cell lysis occurring, genetic revertants or insufficient cellulases made, a secretory pathway was designed based on the type I secretory system:

The secretory apparatus used by E. coli 0157 in α-haemolysin secretion is made up of HlyB, HlyD and TolC. E. coli JM109 still expresses TolC, but to complete the apparatus would require insertion of hlyB and hlyD.

Reliable secretion from the cells requires that the proteins we want secreted contain a secretory-signal sequence. Unfortunately there seems to be no such consensus sequence for secretion of proteins from E. coli, secretion being based instead on the protein's tertiary structure. As such, we have hypothesised that producing fusion proteins with C-terminal domain of HlyA should result in the proteins being secreted.

"

"