Team:Heidelberg/Project/Sensing

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Project - Sensing

Abstract

Bacteria have the ability to sense gradients of chemoattractants in their environment by specific receptor molecules which are present in the outer bacteria membrane. Our aim was to make use of bacterial chemotaxis in order to generate a "killer" strain which is able to detect and finally kill a "prey" strain by chemotaxis induced movement towards it. For this purpose we cloned the LuxS gene of Vibrio harveyi in an expression plasmid. LuxS encodes the Autoinducer-2 synthase, an enzyme that is essential for the production of the chemoattractant Autoinducer-2 (AI-2). We wanted to transform the "prey" cells with this expression plasmid in order to establish a concentration gradient of AI-2, which can be sensed by the "killer" strain. To make the "killer" strain sensitive towards AI-2, we generated two different chimeric receptors consisting each of the periplasmic ligand-binding domain of LuxQ, the natural receptor for AI-2, and the cytoplasmic part of the chemotaxis receptor (Tar). To allow proper folding and signal transduction we included either the second transmembrane domain of the LuxQ receptor or the Tar receptor in the chimeric receptor sequence. In addition to the chimeric receptor sequence we wanted to co-express from the same plasmid also LuxP, a cofactor which is essential for AI-2 ligand binding of the LuxQ receptor. We were successful in the cloning of all constructs mentioned above. The chimeric receptors were expressed in transformed bacteria as controlled by receptor fusions to the yellow fluorescent protein YFP. To our surprise none of the chimeric receptor constructs showed a polarized localization as expected for chemotaxis receptors. We were also not able to detect chemotactic activity in the transformed bacteria. Future experiments with sequence optimized receptor fusions will have to show if AI-2 is able to induce Tar-based chemotaxis.

Introduction

The main component of the sensing system is chemotaxis to make the killer strain swim towards the prey cells. Chemotaxis of E. coli is one of the best studied systems for signal transduction. [Sourjik, 2004]. It is a classical two component system which usually contains membrane-bound receptors for detecting the gradient of a repellent or attractant, and an intracellular kinase which transfers the signal from the receptor to the end reactor – the flagella- the motion machine in the bacteria. Signal transduction is performed by phosphorylation of diffusible regulator proteins [Sourjik, 2004]. Quorum sensing is used in bacteria for cell-cell communication. Small diffusible molecules, called Autoinducers, are secreted and can be detected by other bacteria in order to sense cell density [Waters & Bassler, 2005]. Through the quorum-sensing system bacteria can synchronize certain behaviour [Waters & Bassler, 2005] and act as multicellular organisms [Vendeville, 2005]. Here, we have combined these two components. The quorum-sensing molecule, Autoinducer-2 (AI-2), serves as a chemoattractant, which can be detected by LuxQ. To make the killer cells sensitive to AI-2, a fusion receptor of LuxQ and the chemotactic receptor Tar has been generated.

Chemotaxis

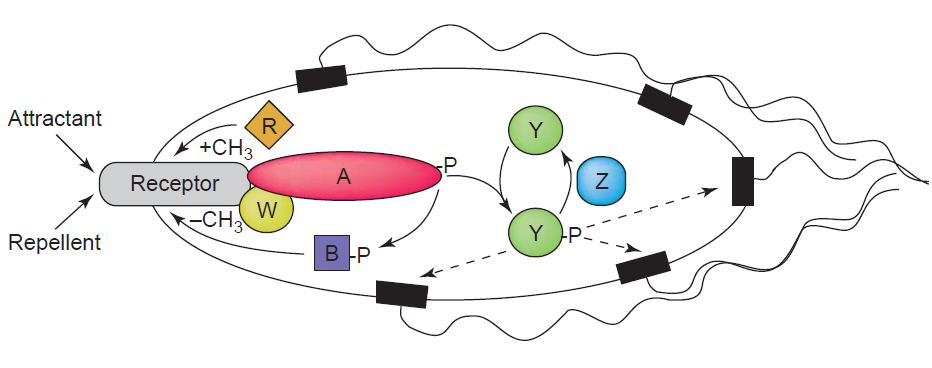

Bacteria sense chemical gradients in their environment and swim towards higher concentrations of chemoattractants or avoid repellents [Sourjik, 2004]. The chemical molecules are detected by specific transmembrane receptors and after a series of signal transduction events subsequently transduced to the flagella, the bacterial motor [Wadhams, 2004]. Most abundant receptors are Tar and Tsr [Sourjik, 2004]. Binding of an attractant results in counterclockwise (CCW) rotation of the flagellar and smooth swimming, while a repellent mediates clockwise rotation and tumbling of the bacteria [Sourjik, 2004]. The key player in signal transduction is CheA, a histidine kinase. Together with the adaptor protein CheW, CheA binds to the cytoplasmic domain of the chemotactic receptor. Its autophosphorylation activity is enhanced by repellents and inhibited by chemoattractants. CheA phosphorylates downstream CheY, which then diffuses to the flagellar and mediates a change in rotation from counterclockwise to clockwise and thus promotes tumbling of the cell. The phosphorylated form of CheY (CheY-P) is rapidly dephosphorylated by CheZ, which is necessary for quick re-adjustment of behavior [Sourjik, 2004].

The aspartate receptor Tar, which is used in this project as chemotaxis receptor, is a 60 kDa protein with about 2500 copies per cell. The smallest units of the receptor are dimers, but the major species in the membrane are tetramers. There is no evidence that Tar can form heterodimers with other methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP). The receptor has a very high helical content of about 80 %. The N-terminal cytoplasmic segment is very small (residues 1-6) and can be altered greatly without affecting the function very much [Mowbray, 1998]. The periplasmic region (residues 31-188) is responsible for ligand binding. In this part the sequence is very little conserved, allowing the binding of various chemoeffectors [Mowbray, 1998]. In the absence of a ligand the periplasmic part forms a symmetric dimer, with each subunit consisting of an antiparallel four-helix bundle. Two transmembrane regions are flanking the periplasmic domain: residues 7-30 (TM1) and residues 189-212 (TM2). Both transmembrane segments have a clear helix pattern. The cytoplasmic region (residued 213-553), which is responsible for signal transduction, has a size of about 37 kDa. It is the most conserved part, with sequence identity of ~70 % between Tar and Tsr. Residues 213-259 are referred to as the linker region and its integrity is crucially important for receptor function [Mowbray, 1998].

Quorum-Sensing

Results

Discussion

References

[Waters & Bassler, 2005] Christopher M. Waters, and Bonnie L. Bassler: Quorum Sensing: Cell-to-Cell Communication in Bacteria, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 319–346, 2005

[Sourjik, 2004] Victor Sourjik: Receptor clustering and signal processing in E. coli chemotaxis, Trends in Microbiology 12(12), 569–576, December 2004

[Vendeville, 2005] Agnes Vendeville, Klaus Winzer, Karin Heurlier, Christoph M. Tang, and Kim R. Hardie: Making sense of metabolism: Autoinducer-2, LuxS and pathogenic bacteria, Nature Reviews 3, 383–396, 2005

[Wadhams, 2004] George H. Wadhams, and Judith P. Armitage: Making Sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis, Molecular Cell Biology 5, 1024–1037, December 2004

[Mowbray, 1998] Sherry L. Mowbray, and Mats O. J. Sandgren: Chemotaxis Receptors: A progress report on structure and function, Journal of Structural Biology 124, 257–275, 1998

[DeKeersmaecker, 2006] Sigrid C. J. De Keersmaecker, Kathleen Sonck, and Jos Vanderleyden: Let LuxS speak up in AI-2 signaling, Trends in Microbiology 14(3), 114–119, 2006

[Sun, 2004] Jibin Sun, Rolf Daniel, Irene Wagner-Döbler, and An-Ping Zeng: Is autoinducer-2 a universal signal for interspecies communication: a comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of the synthesis and signal transduction pathways, BMC Evolutionary Biology 4(36), 2004

[Neiditch, 2005] Matthew B. Neiditch, Michael J. Federle, Stephan T. Miller, Bonnie L. Bassler, and Frederick M. Hughson: Regulation of LuxPQ Receptor Activity by the Quorum-Sensing Signal Autoinducer-2, Molecular Cell 18, 507–518, May 2005

"

"