Team:Heidelberg/Modeling/Phage

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Phage Dynamics Model

On this page you can find a brief summary of the whole modeling part of our team. If you are interested in more details such as mathematical modeling and analyzes, you can take a look at our detailed documentation "Modeling the Phage-induced Infection Dynamics of E. Coli".

Background

Interaction of bacterial populations is a challenging and difficult task for modelers. Bacterial strains respond to external chemicals, secrete their own signals for communication, and even produce killing factors for other bacterial species. Many of these processes are non-linear and proceed at different time and space scales.

Motivation

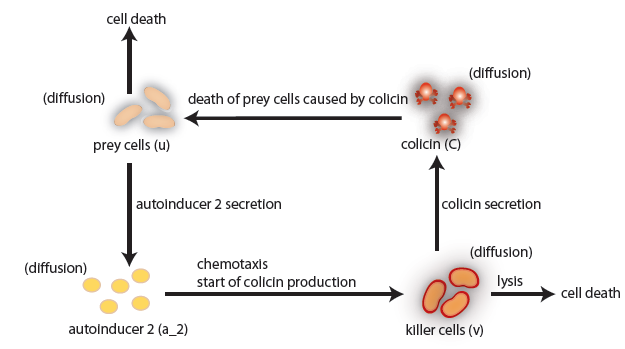

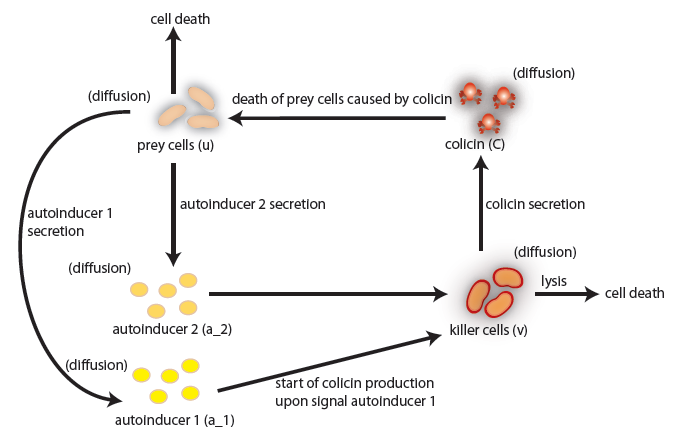

In our project we construct a system of two bacterial strains, in which one population (killer strain) chemotactically senses the chemical signal AI-2 emitted by another population (prey). The killer strain is able to swim towards the prey population using the gradient of AI-2. In the vicinity of prey, the killer strain eliminates the prey. We considered two alternative killing mechanisms: colicin secretion and lambda-phage infection.

Our achievements

We studied the system behavior in space and time using systems of non-linear Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). Systems of PDEs are widely used in science in a variety of problems, from tornadoes prediction to quantum mechanics.

Unlike ordinary differential equations (ODEs), PDEs enable simulation of spatial effects in time, taking into account diffusion effects and spatial fluxes. This is particularly important when the system is not homogeneous. In our case,

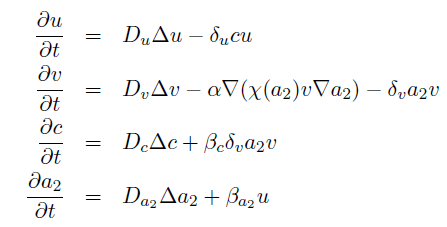

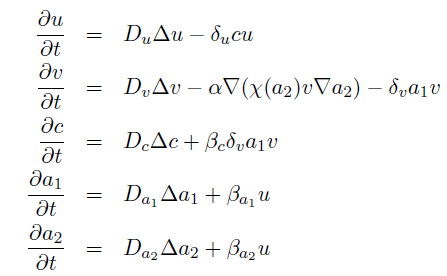

the killer population swims towards the prey population, and chemical signals require a certain time to diffuse through the medium. We designed a minimal system of four non-linear reaction-diffusion PDEs to simulate the chemotactic motility of the killer population towards the prey, and the colicin killing process (Fig. 1 (a), (c)). To simulate the system, we approximated the original system of four PDEs by a system of 10,000 ODEs (method of lines), and solved it numerically using custom-written Matlab code. In a more comprehensive PDE model, we added the fifth PDE to reflect the dynamics of AI-1 (Fig. 1 (b), (d)). AI-1 is secreted by the prey cells and adsorbed by the killer cells, in which it activates the production of the colicin and lysis proteins. The killer cells induced by AI-1 lyse and release the colicin into the surrounding media, resulting in the prey elimination. The extended model allowed us to reflect every key component of the system, and to simulate the interaction of the killer and prey populations at different initial spatial distribution and various system parameters.

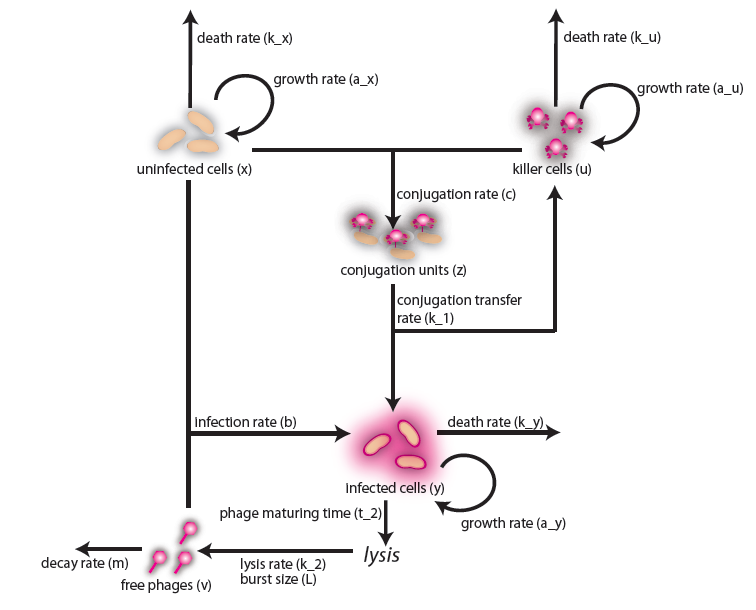

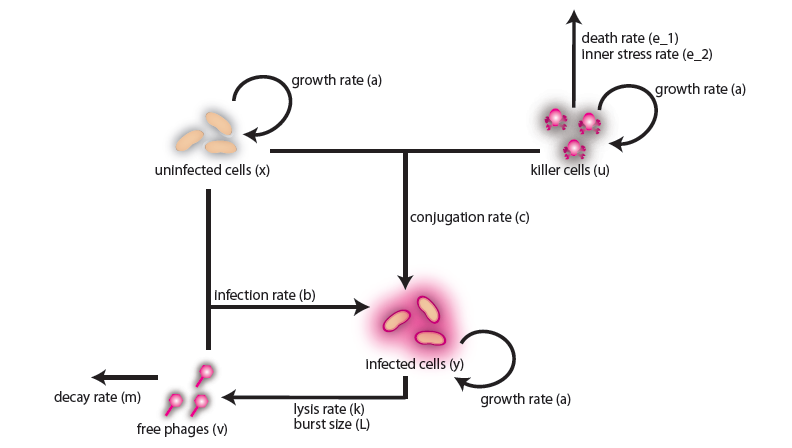

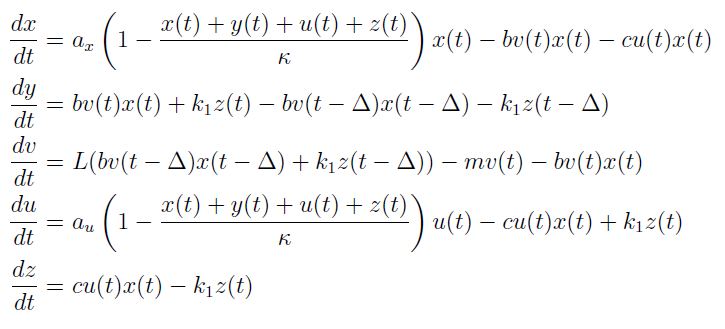

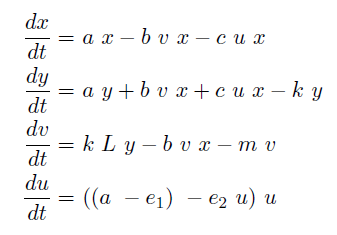

In the case when both populations are well mixed in spatially homogeneous conditions, we modeled another possible killing mechanism – the infection by lambda-phages. Here the prey cells can become infected either by conjugation with killer cells or by free phages, which in both cases leads to lysis of the prey cells and to a release of multiple new phages, initiating a snowball effect. The assumption of spatial homogeneity allowed us to better resolve the temporal behavior of this complex system. To model the lambda-phage infection, we used a system of delay differential equations (DDEs) (Fig. 2 (a), (c)). Unlike ordinary differential equations (ODEs), DDEs allow the temporal change in concentration to depend on concentrations at earlier time points. In our system, we used this method to reflect the fact that phage maturing cannot be arbitrary fast, but takes a certain time to develop. A careful model verification enabled us to simulate the infection dynamics in detail, including the formation of conjugation complexes and the snowball killing effect. To perform a detailed mathematical analysis, we reduced the full model to a simpler ODE version (Fig. 2 (b), (d)). For the ODE system, we determined its steady states with the linear stability analysis and investigated their stability with the initial values analysis, enabling to predict different system regimes upon given parameters and initial conditions.

"

"