Team:Heidelberg/Project/Killing I

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction

Phages - Project Description

Antibiotics are a very powerful way to cure bacterial infections, but their power withers as more and more bacterial strains become resistant to different antibiotics. The great power of evolution leads to chromosomal mutations that not only make bacteria resistant to natural antibiotics, but also to newly developed synthetic ones [1]. Bacteria also have a very effective way to share those resistances with each other, not limited by species boundaries: the transfer of plasmids by conjugation (which will be investigated in more detail in the second part of the project). Multiresistant bacterial strains like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis hinder the usage of antibiotics against infectious diseases, because they cannot be killed by ordinary antibiotics and can give their plasmids to other pathogens, which then become resistant themselves.

Nevertheless, there are some alternatives to antibiotics, which are currently being investigated: bacterial toxins, probiotic bacteria and bacteriophages. Our project consisted in engineering a probiotic bacterium which uses either toxins or bacteriophages as a killing device.

Our sub-team is concerned with the strategy based on phages. Bacteriophages are a group of viruses whose natural hosts are bacteria, which can be human pathogens. There are two types of phages: virulent and temperate ones. Virulent phages infect a host cell and multiply by using the host resources and lyse the host to set themselves free. Temperate phages also can multiply inside a host cell and lyse it to get themselves free (lytic phase), but alternatively they can integrate into the host chromosome (lysogenic phase), remaining dormant until the host conditions get worse. Virulent, non-lysogenic phages are used for the treatment of infectious diseases caused by bacteria since the 1930s. Phage therapy was intensely used until the first antibiotics were discovered in the 1940s. Later, this technique was extensively investigated and used especially in the Soviet Union [2]. Since there are more and more multiresistant bacterial strains, phage therapy becomes interesting again [3].

The special quality of our approach is that we use bacteria as vectors for the phages. This will avoid the consequences of a systemic application of bacteriophages, because they are only released at the site of infection. Smaller amounts of phages are needed, because they are not spreading through the whole body.

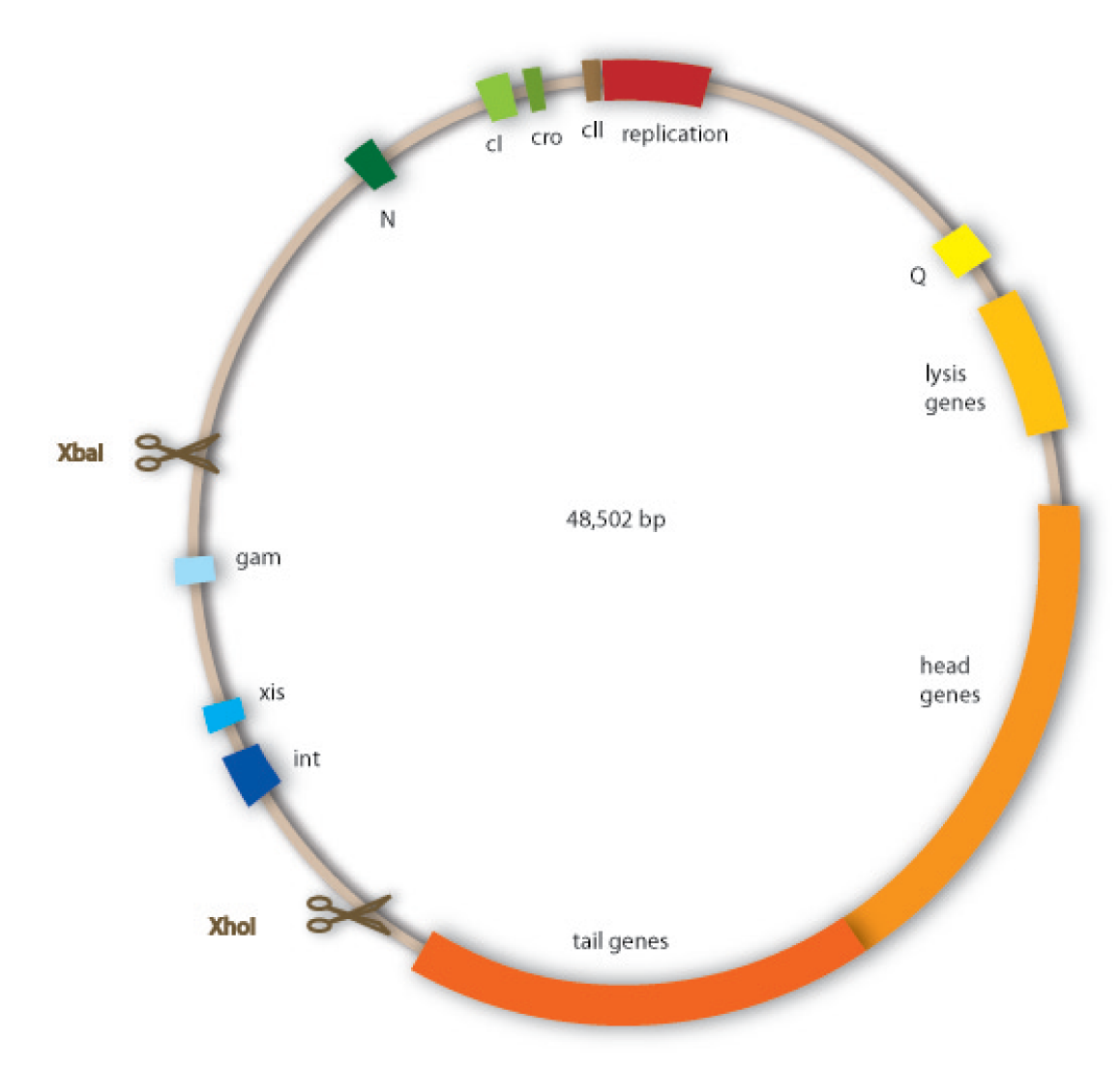

We have decided to use lambda phage for our project since it is an extensively investigated phage which should therefore be easier to handle than less studied ones. Lambda phages are a class of temperate bacteriophages with a 48,502 bp genome consisting of linear double stranded DNA. The genome has a highly mosaic, modular structure. Like for all viruses, there are distinct steps for lambda phage infection. The first step is adsorption. Lambda phages have receptors at their tail fibres, which bind specifically to mannose transporters of Escherichia coli. These receptors are not able to bind stably to structures on other bacteria strains and are therefore responsible for the host specificity of the lambda phage. After adsorption, the lambda phage injects its genome into the host cell. In the environment of the host, the linear DNA circularizes at the so called cos sites: these are 12 bp complementary overhangs at the ends of the genome.

As temperate phages, lambda phages are able to undergo either a lytic or a lysogenic cycle. When undergoing a lysogenic cycle, the phage integrates its genome into the host genome and stays there as a stable prophage. In this state it will be replicated passively with the host genome. It will not lyse the cell and multiply without an external trigger – for example if the host cell is stressed by DNA damage. If carrying out a lytic cycle, the lambda phage also injects its genome into the host cell. This will then be replicated autonomously, viral proteins will be produced, first for the formation of new phage particles, which are formed via self-assembly, and second for the lysis of the host cell, upon which the newly produced phages are released. The lambda phage has a very complex regulatory network that controls which cycle to carry out.

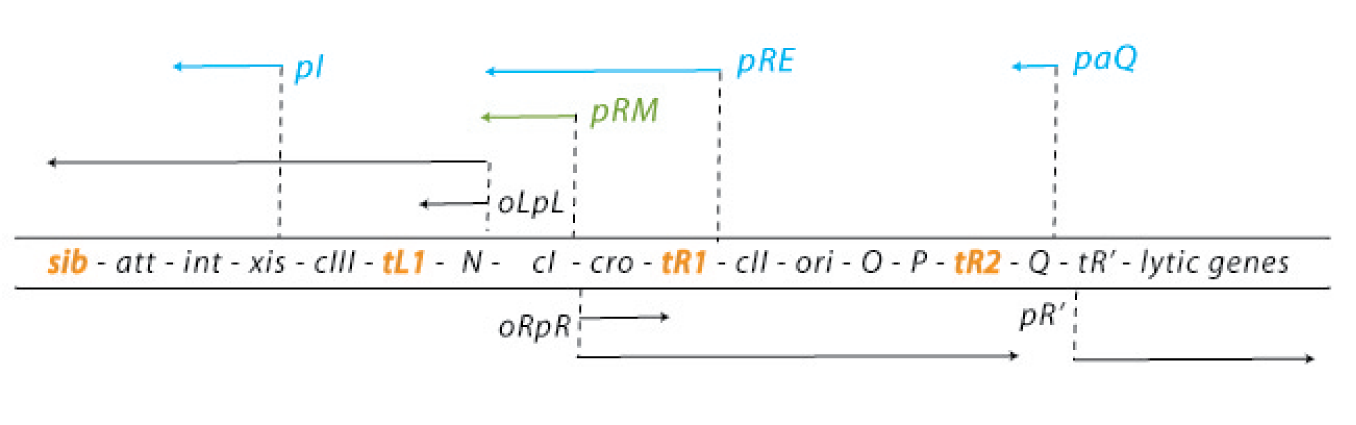

The default mode of this network is the lytic growth. This is carried out in three steps: 1. After the injection of the genome, transcription starts from the promoters pL and pR. This early transcription has two products - the regulators N and cro - and is attenuated at the terminators tL1 and tR1. Cro acts as a weak repressor for the pL and pR promoters, allows little but steady transcription from these promoters and thereby facilitates the lytic state (because cII concentrations are kept low – see below). N is an antiterminator that enables the RNA polymerase to overcome the tL1 and tR1 terminators and to read the DNA up to the sib and the tR2 terminator, respectively. 2. With the help of N, the delayed early genes are transcribed. The products are the lysogenic regulators cII and cIII as well as the lytic DNA replication functions O and P and the late gene regulator Q. (N is critical for the switch to the lytic state: cells carrying N on a plasmid and thereby expressing it strongly allow a very effective lytic mode of the phage – they from clear plaques!) 3. An accumulation of Q makes the RNA polymerase resistant to the tR’ terminator and thereby allows expression of the late genes, which are essential for the lytic cycle. They encode for the viral coat proteins and for lysis proteins. These late genes are expressed with a delay after the delayed early genes, which results from the threshold concentration of Q that has to be accumulated to overcome the tR’ terminator.

In contrast, the lysogenic state is also initiated during the transcription of the early delayed genes: 1. Under lysogenic conditions, cII is able to accumulate over a threshold level. Then it can bind to the pI, pRM and paQ promoters, thereby initiating the expression of int, cI and repressing the expression of Q, respectively. The int gene encodes a protein called integrase, which integrated the phage genome into the host genome. 2. CI binds to the early operators oL and oR and represses transcription from pL and pR. Repression of transcription from pR inhibits the transcriptional activation of the ori of the lambda phage genome and thereby replication. So cI maintains the stable lysogenic state after cIi has switched the genetic cascade of the lambda phage in favour of lysogeny. 3. During the prophage state, cI is expressed continuously. If another phage injects its genome into the host cell of a prophage, cI binds to regulatory sequences on this second genome and prevents any transcription, thereby making the host immune to super infections.

Whether to undergo a lytic or a lysogenic mode depends on the multiplicity of infection and the physiological conditions of the bacterial cell. Many phages infecting a cell favour lysogeny. Rich nutrition of the bacterium favours the lytic state, because it increases N expression levels. Since lytic and lysogenic genes are under the control of the same promoters, the critical point for the decision of a state are the RNA and protein levels, influenced by the activity of degrading enzymes [4][5][6][7][8][9].

Our work focused on engineering a non-lysogenic phage, because we wanted to produce an efficient killing module for the probiotic bacterium. In preventing the phage from undergoing a lysogenic cycle, we assure that it will kill the target bacteria as fast as possible and without extern triggers. For this task we aimed at discarding the int gene from the phage genome, so that it would be incapable of integrating into the host genome.

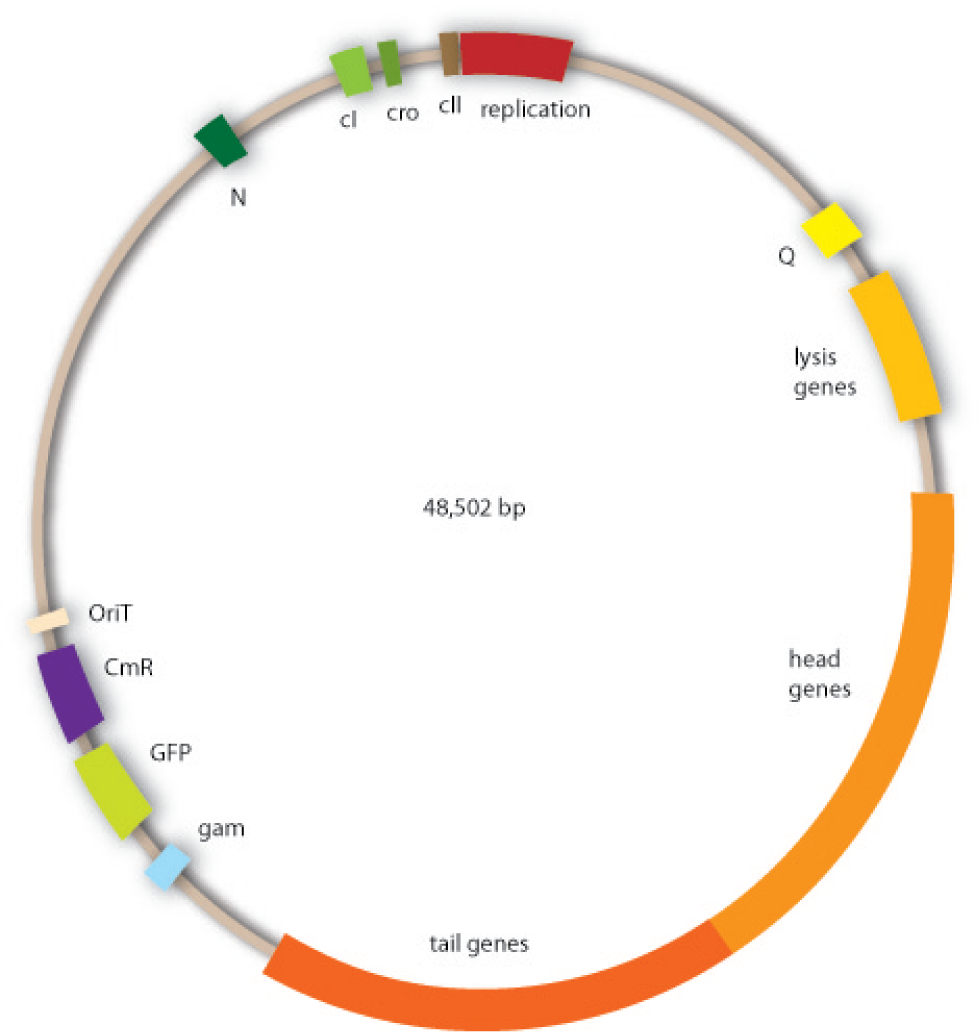

Cloning work with the lambda phage genome is tricky, because it contains few single-cutter restriction sites. Therefore we had to cut out one fragment containing the int, the xis and another gene, gam. Xis and int can and shall be discarded, but the gam gene codes for a protein that prevents the overhanging single strains at the cos sites from being degraded by host enzymes. So we would need the gam gene in our engineered phage. This is why we designed an insert for the phage to put in the remaining genome after cutting out the fragment containing xis, int and gam. This insert contains gam, and an antibiotic selection marker to be able to select those bacterial clones that contain the lambda genome.

We also added a GFP gene for visualizing and measurement purposes. To be able to later modify this phage insert again, we added special restriction sites to only cut out the non-phage genes.

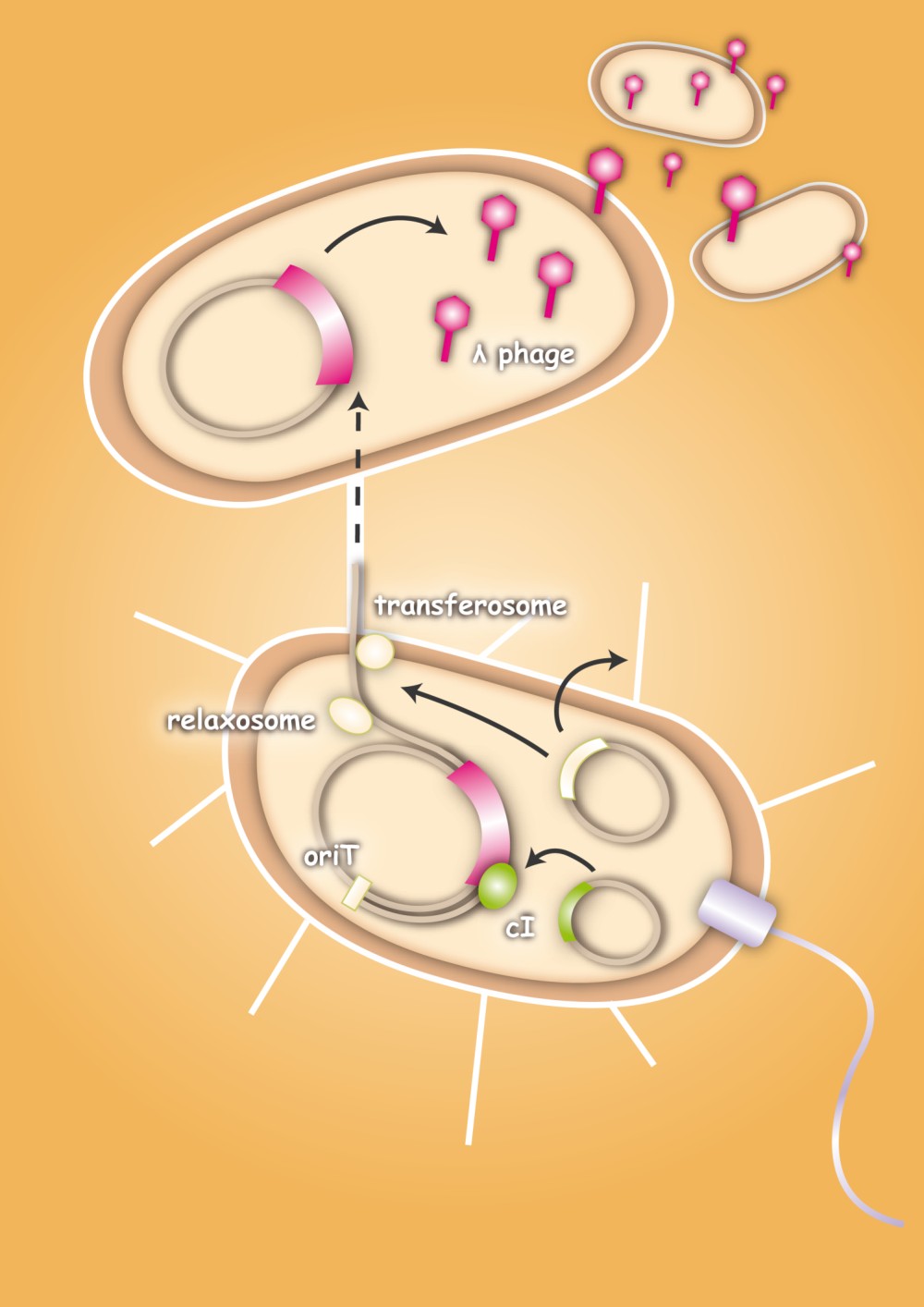

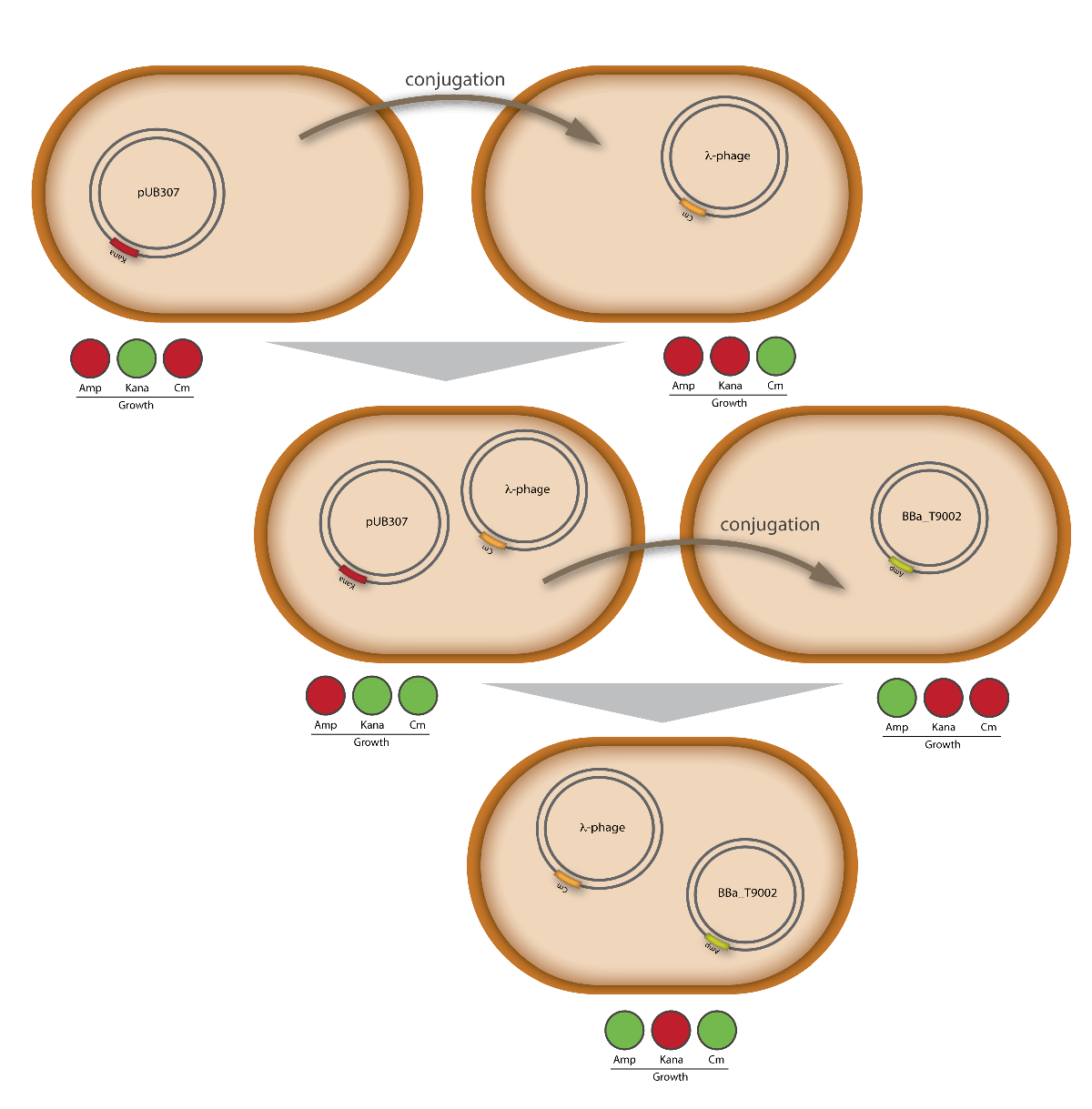

When designing the probiotic bacterium to kill pathogens, we had one problem to solve: the probiotic bacteria should not be lysed by the release of the phages, but the phages had to get into the target bacteria. Therefore we decided to use conjugation for this task. Conjugation is the most important bacterial tool to transfer genetic information between and across species. It enables them to adapt very fast to environmental conditions - antibiotic resistances are also spread via conjugation. Our project aims at fighting infectious diseases which cannot be treated with antibiotics any more because of these resistances. We decided to fight pathogens using their own weapon!

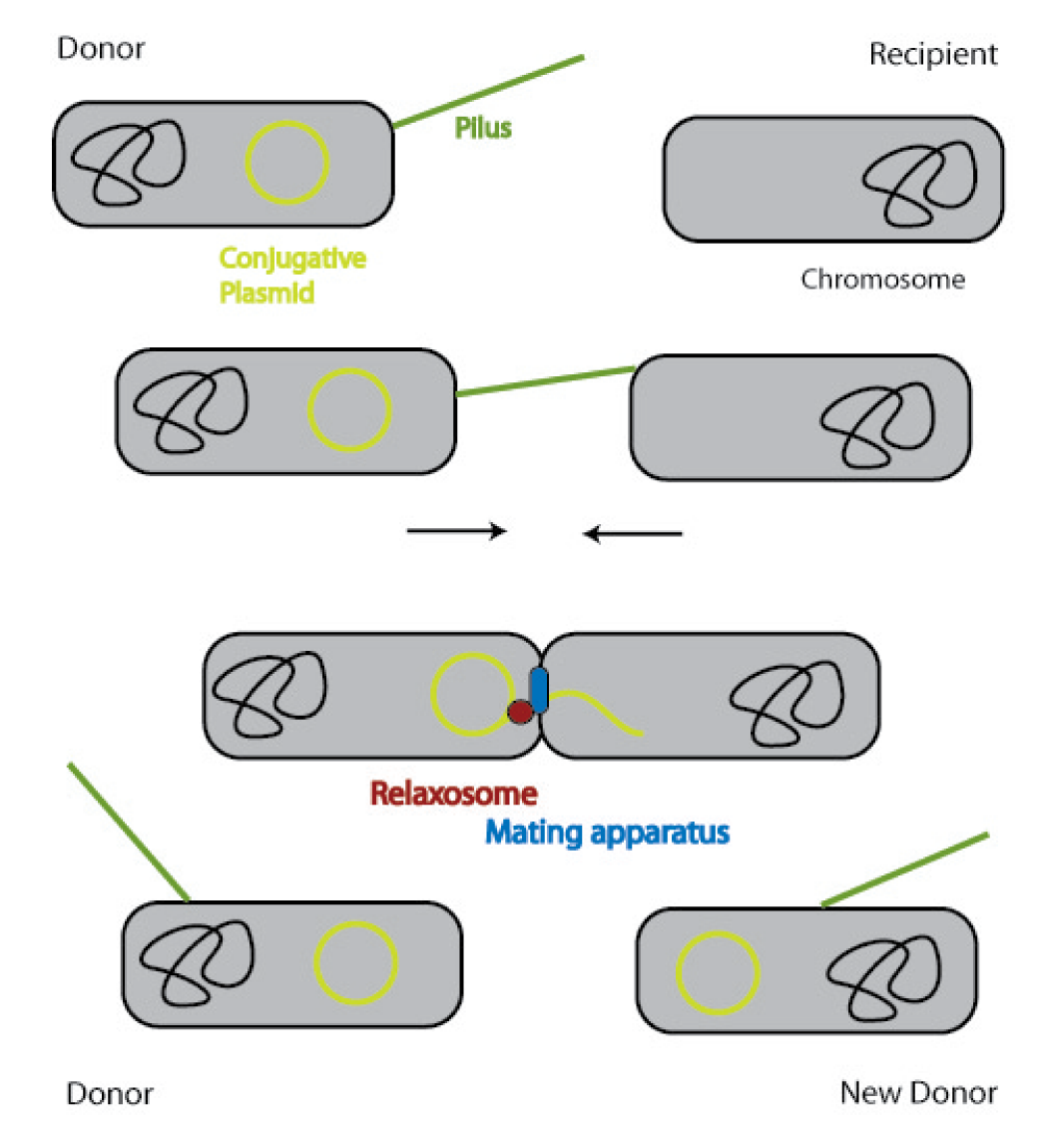

In general, conjugation is the unidirectional transfer of genetic information from a donor cell to a recipient. This genetic information can be a conjugative or mobilizable plasmid or a transposon. Normally, conjugation needs direct cell contact and the formation of a plasma bridge between the cells.

A conjugative plasmid of gram negative bacteria contains a characteristic set of genes and sequences. The tra locus includes the genes for the sex pili and for proteins that carry out synthesis, replication and transfer of the DNA during mating.

The sex pili are formed by pilin and regulatory proteins. These are polymeric structures that extend into the periphery from the surface of the donor cell and can attach to the surface of other bacteria and initiate conjugation. They do make the physical contact between the cells by retracting, but they do not form the channel, through which the DNA is shuttled.

After the initiation of conjugation, a relaxase creates a nick in one of the strands of the conjugation plasmid at the nic sequence of the origin of transfer (oriT) and unwinds the strand to be transferred (the T-strand). If the relaxase (TraI in IncP plasmids) works in complex of many proteins, this is called the relaxosome. The T-strand is unwound from the plasmid and transferred into the recipient in a 5’-to 3’ terminus direction. During this process, the relaxase protein stays bound to the 5’ end of the T-strand. The transfer is catalysed by an enzyme (called TraG in IncP plasmids), which possibly acts by connecting the relaxosome at the 5’ end of the T-strand with the mating complex (mating complex are all proteins that are important for the formation of the plasma bridge between the two cells). The remaining strand is replicated using rolling circle replication. The transferred strand is complemented in the recipient cell.

Since a conjugation plasmid contains all the information necessary to transfer DNA, the recipient becomes a donor after conjugation [10].

There exist many variations of this classic system of conjugation. One is a two component system, consisting of a helper plasmid and a mobilizable plasmid. Most of the proteins needed for conjugation are trans acting elements, they do not have to be on the transferred plasmid, but can either be part of the chromosome or be on another plasmid, a so called helper plasmid. The only cis acting element needed for the transfer of a plasmid is the oriT sequence. It consists of the sequence, where the relaxase nicks the DNA, the nic, and some genes called mobilizable (mob) genes. Together they make about 500bp. The mob genes encode for example accessory proteins that bind to the DNA sequence at and around the nic sequence and assist the relaxase. If they are included in an arbitrary plasmid, it will be mobilized and conjugated by the helper plasmid. This two component system has some important advantages: You do not need to put the genetic information you want to transfer on a big conjugation plasmid like an F-plasmid or an RP-plasmid. This makes conjugation much faster and more effective, because the time and the effectivness of conjugation depend on the length of the plasmid to transfer. Additionally, you can use every kind of plasmid as a mobilizable plasmid. This makes it perfect for our purpose: We can use the lambda genome as a mobilizable plasmid in cloning an oriT into it and providing a suitable helper plasmid.

There are different groups of conjugative plasmids that can also function as helper plasmids in enterobacteria: the classic F-plasmid, RP4/RP1 among others. We decided to use an IncP (incompatibility group P) plasmid and a complementary oriT as our conjugation system, because they proofed to be very efficient [11]. These are plasmids with a broad host range that carry multiple antibiotic resistance genes. The plasmids of this group do not need host-chromosome encoded components for the mobilization of plasmids, like RSF1010 for example needs [12]. Therefore they have a very broad range of hosts and fit in very well in the modular concept of synthetic biology.

The prototype of InP plasmids is the RP4 plasmid, which is a close relative of the RP1 plasmid of which we use a derivative. The tra genes are organized in two operons, tra1 and tra2. Tra1 encodes for all of the DNA transfer and replication system, especially for the relaxosome, the complex, which initiates the transfer replication [14]. Tra2 encodes for proteins necessary for mating pair formation.

The plasmid we use is called pUB307 [15][16]. It is a derivate of RP1, which lacks the transposon Tn1 (Ampicillin resistance cassette) by spontaneous excision.

To avoid that our probiotic bacteria, which would contain and transfer the phage to the target pathogenic bacteria, would also be killed by the phage, we used the natural way to make them immune. Therefore we took the lambda cI gene and put it behind a constitutive promoter. The cI protein will then prevent the expression of the lambda genome in our bacteria and prevent them from being lysed. [back]

Cloning strategy

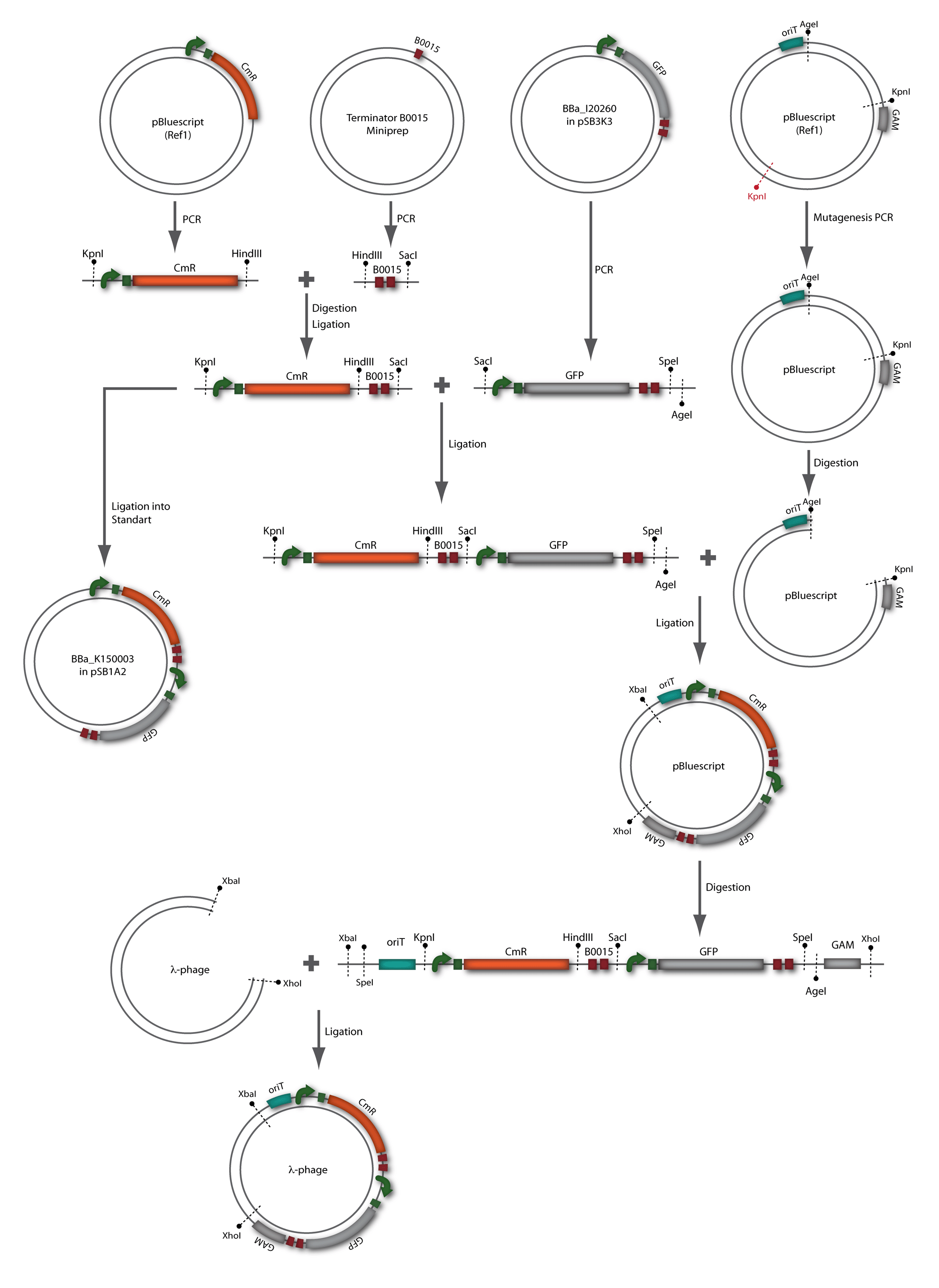

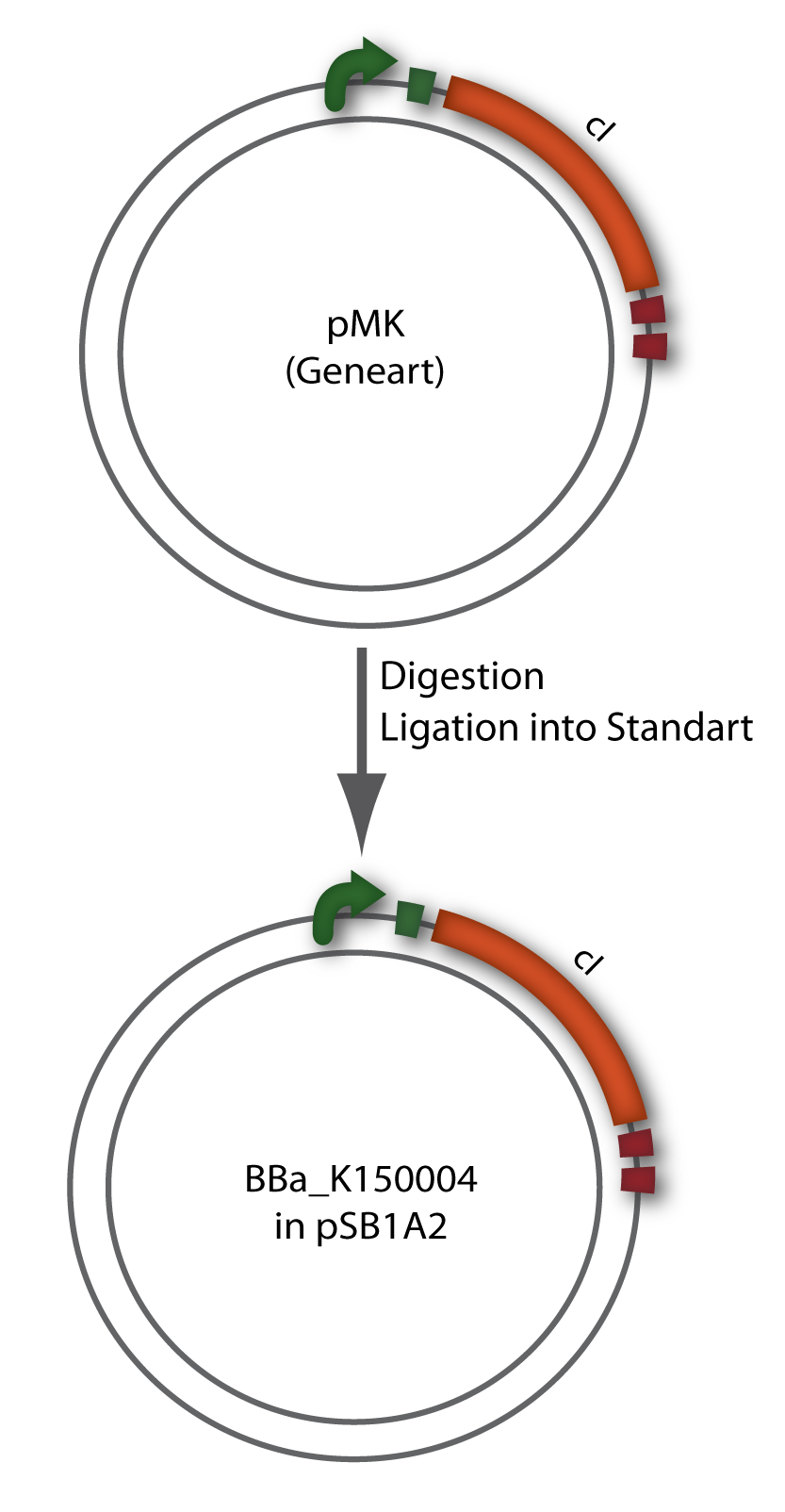

Our goal to clone a modified bacteriophage λ which can be transported by conjugation, allows the selection of infected cells through a chloamphenicol resistance and harbours GFP for visualization was designed in two strategies whereas strategy two builds on strategy one. A detailed description of the two strategies can be seen below (see figure 1.6 and 1.7). The used λ cI protein generator was synthesised by geneart and just transferred in a standard plasmid as it can be seen in figure 1.8.

Phage cloning strategy one

Phage cloning strategy two

Bacteriophage λ cI cloning strategy

Results

phage cloning strategy one

cloning

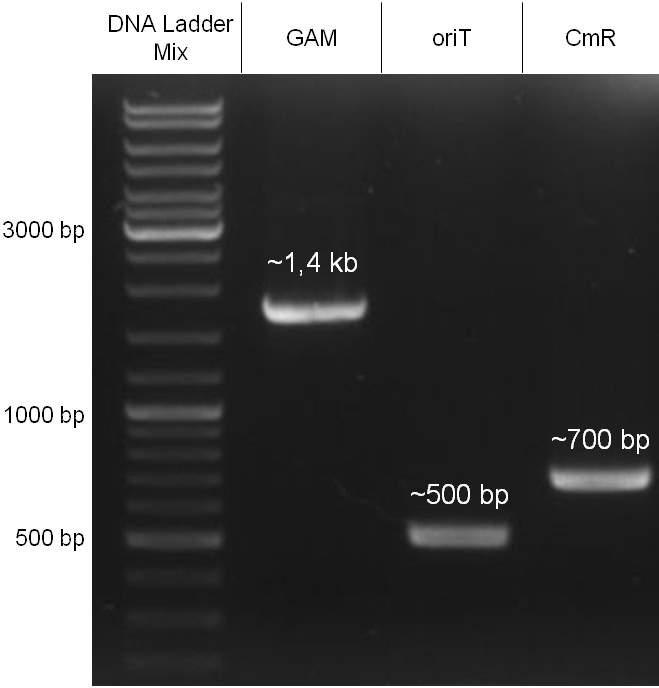

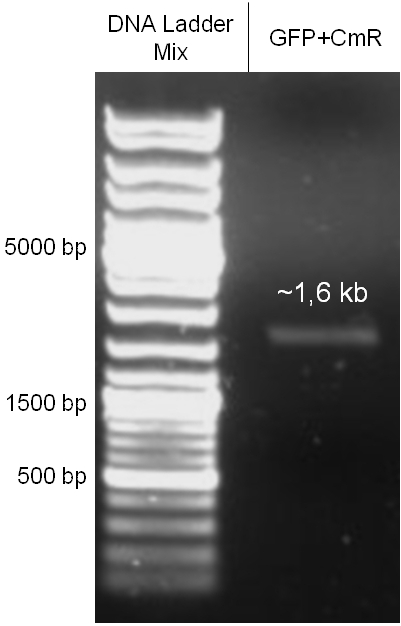

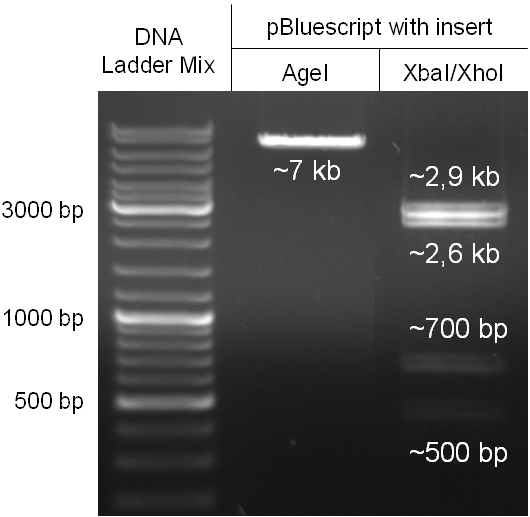

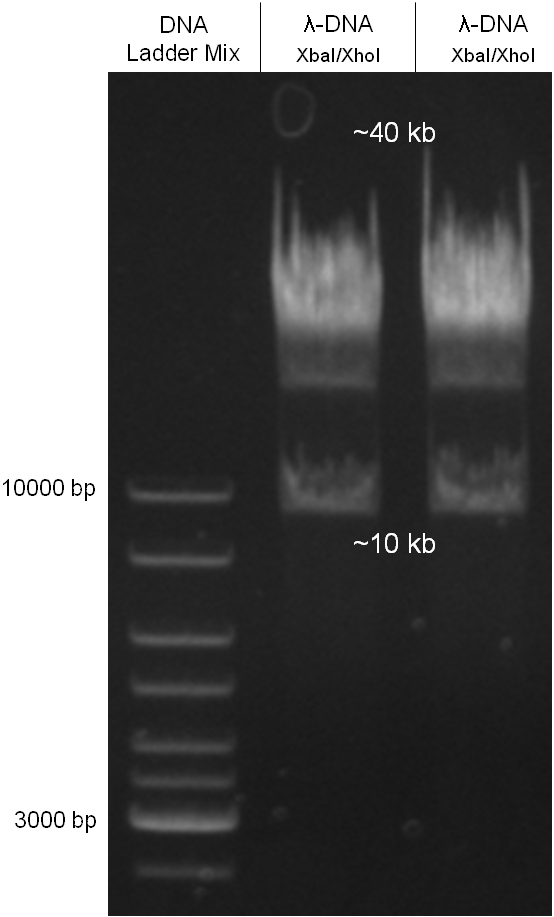

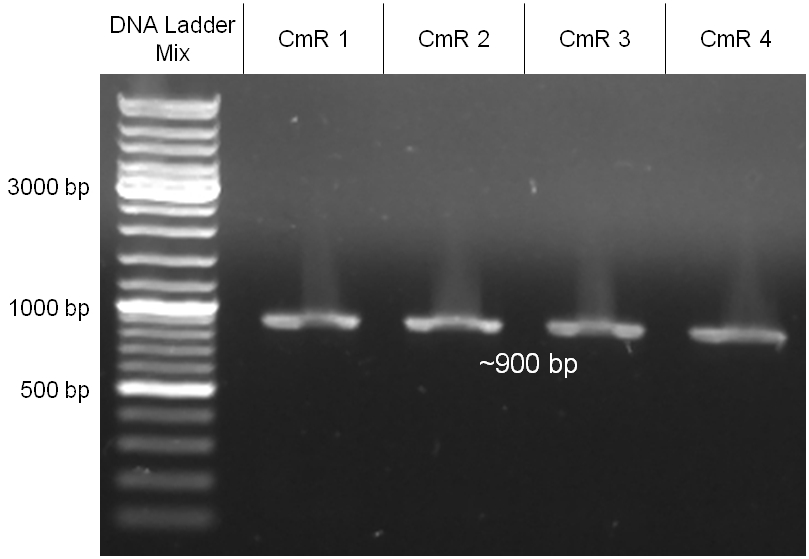

In our strategy, four fragments had to be ligated into the bacteriophage λ. We decided to first ligate the four fragments into a standard high-copy cloning vector (pBluescript SK II), to better control the ligation success and to amplify the insert to be ligated in the phage. The four parts making up the insert were: the λ phage GAM fragment, a chloramphenicol resistance cassette (CmR) for selection of successfully modified phages, a GFP cassette for visualization of the phage and an E. coli oriT (R), which allows the conjugation of the harboring plasmid, provided the cell contains also the so called helper plasmid (pUB307, a RP4 derivate). The GAM fragment was obtained from the λ phage, the oriT from pMMB863, a plasmid bearing the RP4 oriT - kind gift of Prof. Bagdasarian (MSU). Both fragments were amplified by PCR, which allowed us to flank our insert with desired restriction sites simply by designing appropriate primers (see figure 2.1.1). The CmR was amplified by PCR from pDEST15; at this stage we introduced a Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) at the end of the coding region of the chloramphenicol resistance gene, since we wanted to express the cmr and the gfp genes from a bi-cistronic operon (see figure 2.1.1). For this purpose, we cut the registry part BBa_I20260 (into pSB3K3) with ScaI, to obtain blunt ends inside the GFP cassette between the RBS and the start codon of the GFP. The CmR coding region plus the RBS at the end of it was then blunt-end cloned into the ScaI-digested BBa_I20260. This new part was then again amplified by PCR introducing new specific sticky ends on the primers (KpnI/AgeI) (see figure 2.1.2) and cloned together with the oriT (XbaI/KpnI) and the GAM fragment (AgeI/XhoI) in one ligation into pBluescript SKII digested with XbaI/XhoI. In this state (see figure 2.1.3) the insert could be sequenced completely and unwanted XbaI restriction sites were removed by mutagenesis PCR (see figure 2.1.4) before it was transferred into the XbaI/XhoI digested λ phage (figure 2.1.5). The success of this ligation could be proven by growth of infected cells on chloramphenicol but not on ampicillin which is granted by the pBluescript vector and by conjugation of this chloramphenicol resistance. Unfortunately the used λ phage contained a mutation (Sam7) which made it impossible for the phage to lyse its host. Therefore the strategy should be repeated using another λ phage. Nevertheless it could be shown that our strategy in principle worked

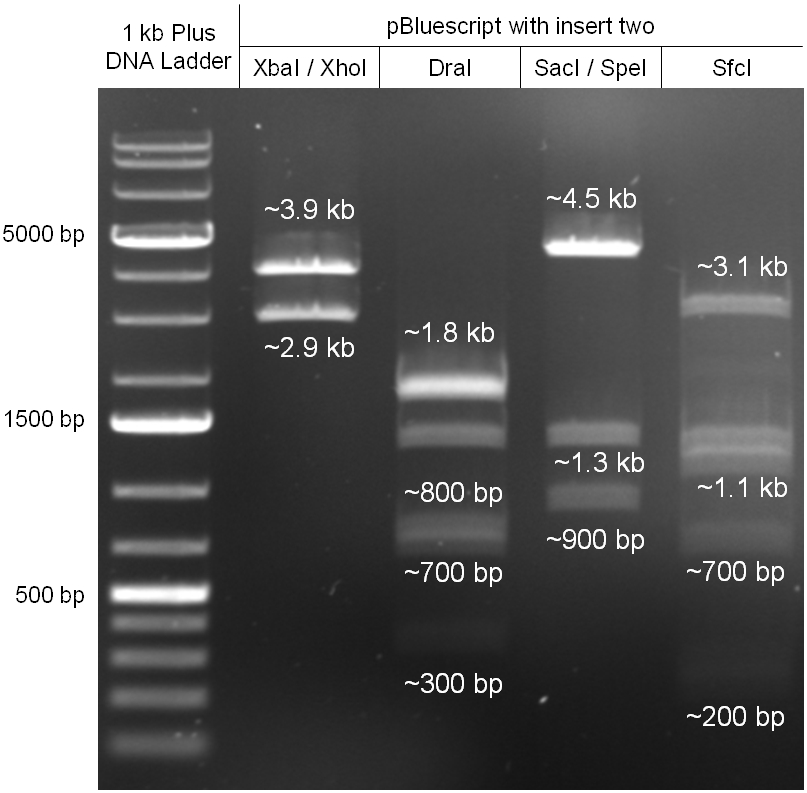

Figure 2.1.3: Restriction digestions of the complete insert containing oriT, CmR, GFP and the GAM fragment in pBluescript II with indicated restriction enzymes. Note that our insert still contained unwanted XbaI restriction sites. Lanes were merged on the computer to remove lanes that are not interesting for this project. |

|

proof of conjugation

For this test E. coli Top10 cells harboring our helper plasmid pUB307 which were not able to grow on ampicillin or chloramphenicol were used to conjugate this plasmid in E. coli Top10 infected with our modified phage which therefore were able to grow on chloramphenicol. The culture of cells infected with the phage did only grow in chloramphenicol but not in ampicillin or kanamycin what proofs that our insert was introduced in the λ phage and did not still exist in its cloning vector pBluescript SK II since this one should also provide the cells with a resistance to ampicillin. The conjugation leads to cells able to grow on kanamycin and chloramphenicol but not on ampicillin. In another conjugation step it could be shown that the λ phage can be transported by conjugation in E. coli Top10 harboring the part BBa_T9002 on pSB1A3 since the resulting bacteria were able to grow on chloramphenicol and ampicillin. Summarizing we could proof that our modified λ phage can be transported by conjugation in presence of the helper plasmid pUB307.

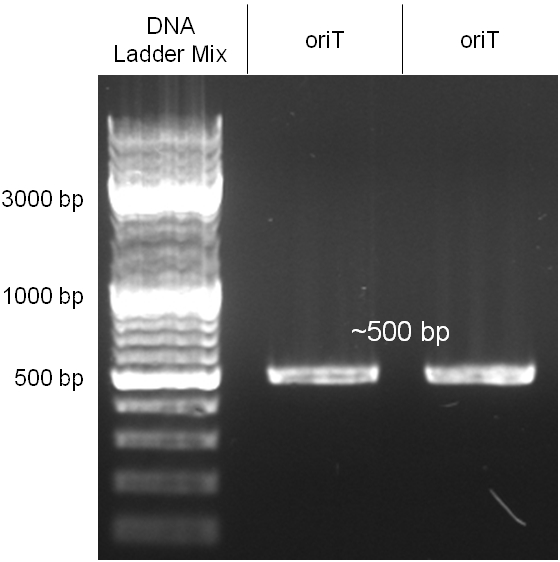

oriT

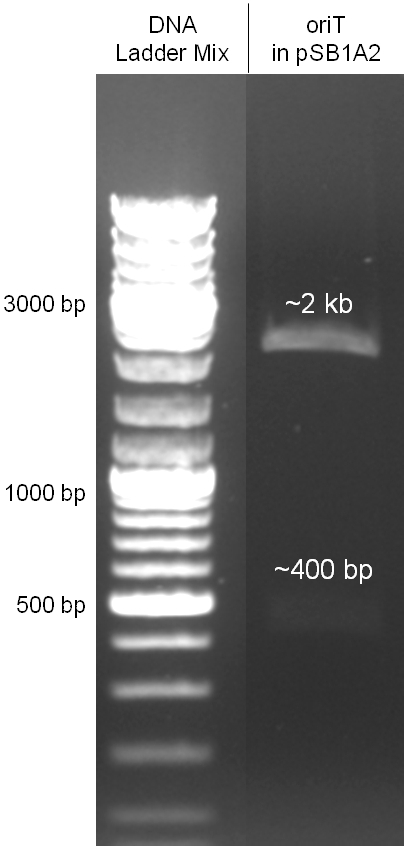

The oriT we received from Prof. Bagdasarian (Michigan State University) was amplified by PCR using pMMB863 as template, which is a cloning plasmid containing the RP4 oriT. During this amplification standard prefix and suffix were added and finally this part cloned into the standard plasmid pSB1A2 using the restriction enzymes PstI and EcoRI. The PCR product can be seen in figure 2.2.1, the successful control digestion of the final product in figure 2.2.2. The sequencing with the VF2 and VR primer showed, that our standardized oriT has exactly the same sequence as the BioBrick BBa_J01003, an oriT that is already in the registry.

[back]

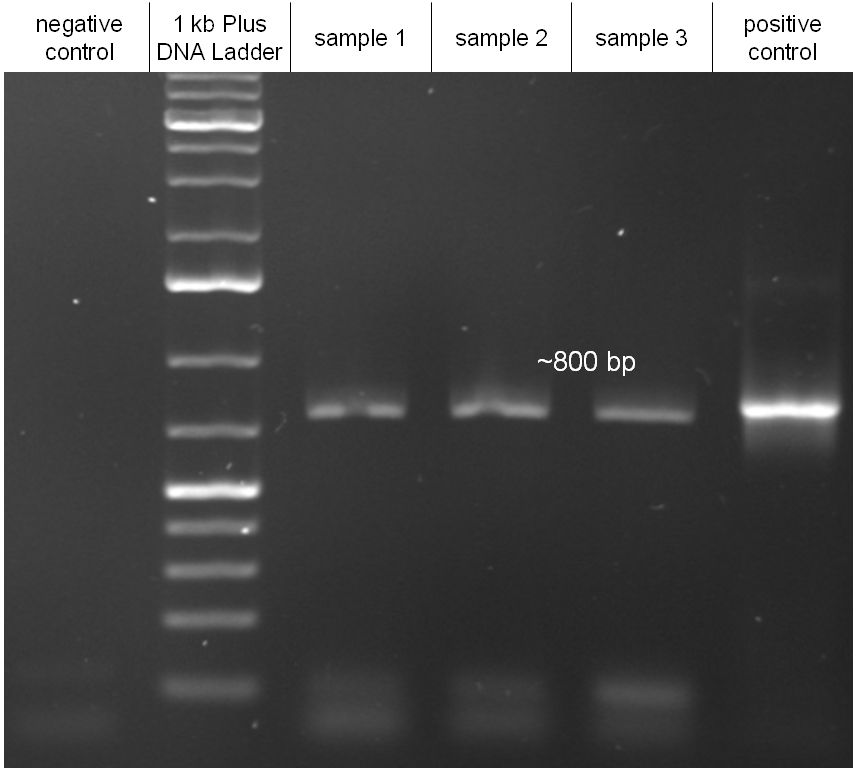

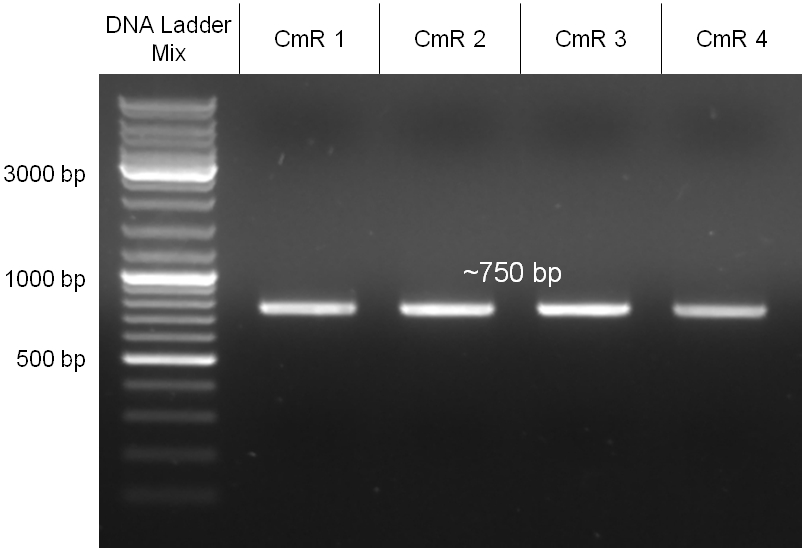

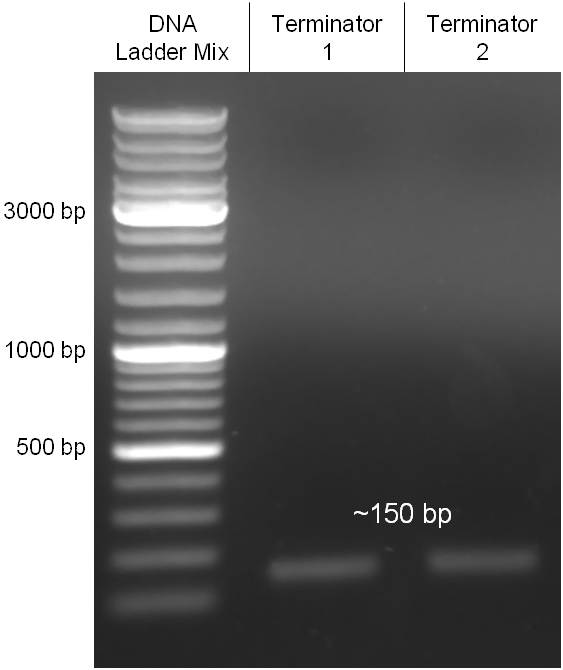

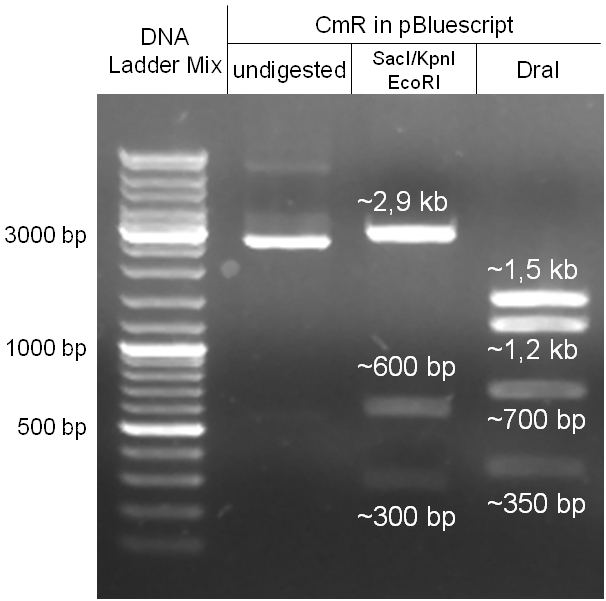

Chloramphenicol resistance cassette

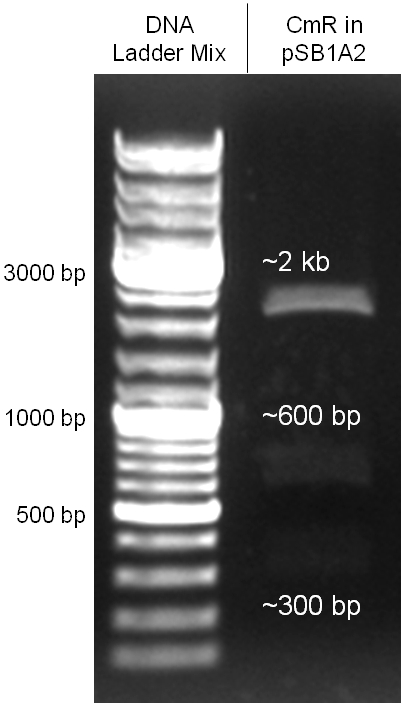

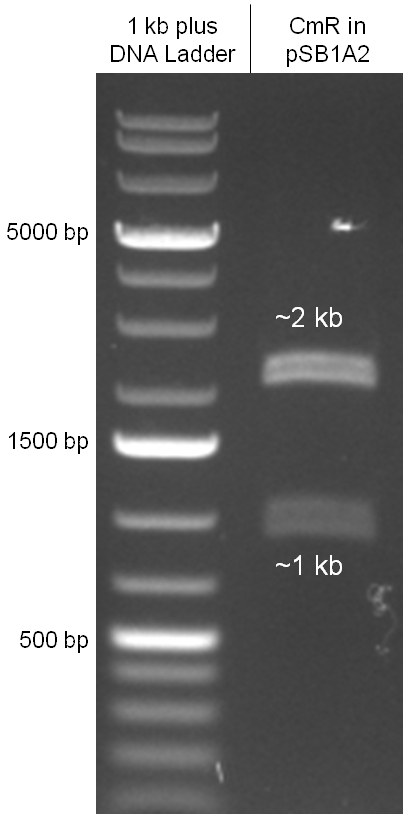

The coding chloramphenicol resistance sequence together with its promotor and ribosome binding site was amplified by PCR out of the pBluescript plasmid with the complete insert from the first phage cloning strategy (see figure 2.3.1). The terminator BBa_B0015 was amplified by PCR out of its standard plasmid pSB1AK3 as well (see figure 2.3.2). Because of the overhangs added by PCR the chloramphenicol resistance could be digested with KpnI/HindIII and the terminator with HindIII/SacI to generate sticky ends, necessary to ligate these two fragments in pBluescript digested with KpnI/SacI. A control digestion showed, that this ligation was successful (see figure 2.3.3). In the next step, the whole chloramphenicol resistance cassette was amplified by PCR out of pBluescript (see figure 2.3.4) in order to add the standard prefix and suffix to ligate it finally in the standard plasmid pSB1A2. A control digestion can be seen in figure 2.3.5. Finally, the EcoRI restriction site within the chloramphenicol resistance cassette, which isn’t allowed by the BioBrick standard, was removed by mutagenesis PCR. The finished part was confirmed by sequencing (using VF2 and VR) and a control digestion (see figure 2.3.6).

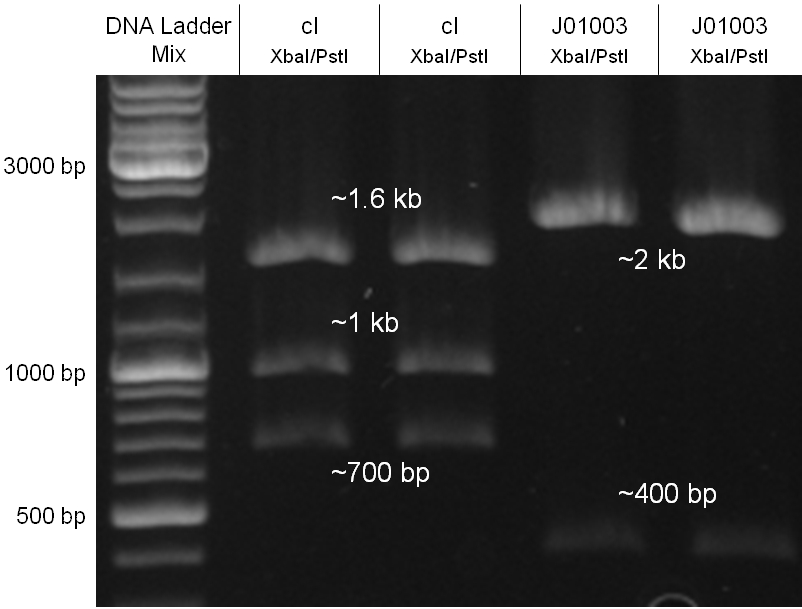

Figure 2.3.5: Control digestion of the complete unmutated chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the standard plasmid pSB1A2 with EcoRI and PstI. An EcoRI restriction site within the cassette, which isn't allowed by BioBrick standard, yields to three instead of the two expected bands. The 2 kb band represents the pSB1A2 backbone. |

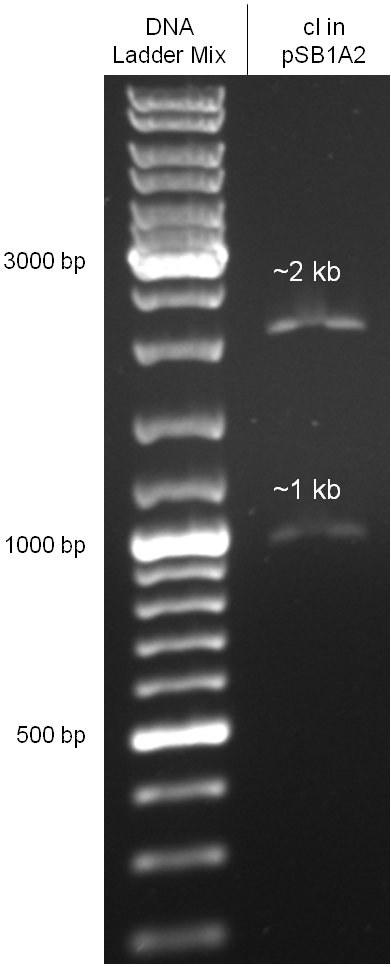

Figure 2.3.6: Control digestion of the complete mutated chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the standard plasmid pSB1A2 with EcoRI and PstI. The EcoRI restricition site, led to the unwanted third band in figure 2.3.5 was removed by mutagenesis PCR. The sizes of the insert (~1kb) as well as the pSB1A2 backbone (~2kb) are correct. |

[back]

phage cloning strategy two

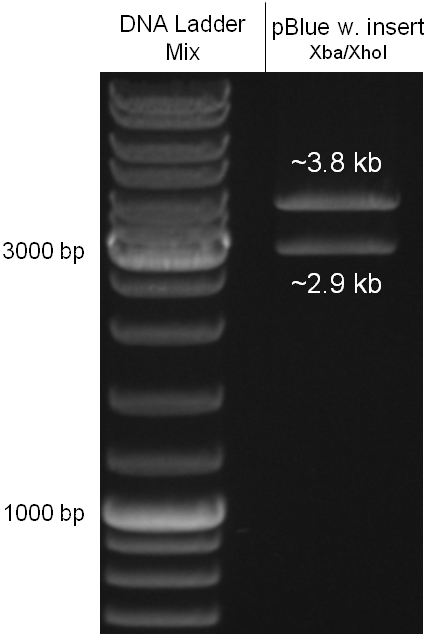

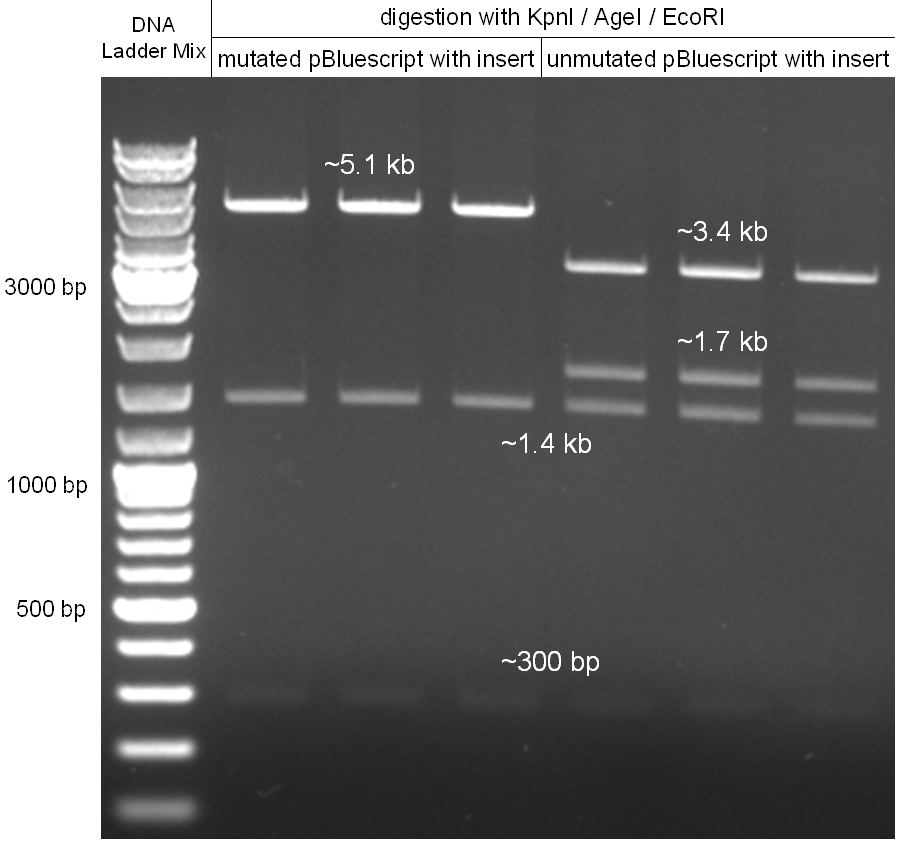

For this second strategy the end product of strategy one (the insert in pBluescript II, see 2.1) as well as the finalized chloramphenicol resistance cassette (CmR) (see 2.3) were used. The difference between cloning strategy one and two is the control of the CmR and GFP cassette. In strategy one these two parts are bicistronic under control of one promotor whereas in strategy two they are designed as two distinct protein generators. For succeeding in this strategy first one unwanted KpnI restriction site in the pBluescript vector including the insert from strategy one had to be removed by mutagenesis PCR. The success of this mutagenesis can be seen in figure 2.4.1. Afterwards the vector was cut with AgeI/KpnI, the bicistronic CmR and GFP cassettes removed and these two parts as distinct cassettes inserted into the vector still bearing the oriT and GAM fragment. Figure 2.4.2 shows the control digestion of pBluescript SK II with the new insert. This new insert which was again restricted by XbaI/XhoI was than planned to clone in the λ phage in the same way as described in 2.1. Unfortunately this could not be achieved due to a lack of time.

cI

Since the cI part BBa_J01101 has the wrong sequence and therefore isn’t functional, we decided produce a new bacteriophage λ cI repressor by ordering the cI sequence including a promotor (BBa_J23101), RBS (BBa_B0032) and terminator (BBa_B0015) from geneart. The sequence, which we got from NCBI, was optimized for high expression levels in E. coli using Geneart’s GeneOptimizer technology. Although the amino acid sequence remained the same, an unwanted EcoRI restriction site was introduced, which had to been removed by mutagenesis PCR. Since the standard prefix and suffix were already included in the sequence ordered from geneart, the cI cassette could easily be cloned in the standard plasmid pSB1A2 using the restriction enzymes XbaI and PstI (see figure 2.5.1). The finished part was confirmed by sequencing (using VF2 and VR) and a control digestion (see figure 2.5.2) and then used for characterisation.

[back]

Outlook

Our strategy to infect and kill bacteria with bacteriophages by conjugation, keeping the killer strain immune to such infection, in our opinion worked very well. We could show that our modified λ phage can be passed from the killer strain onto a recipient strain by conjugation. Using a λ phage which undergoes solely the lytic phase (since it lacks the cI) we showed that the killer strain is immune to infection thanks to the high levels of the cI protein, expressed from our construct BBa_K150004. Furthermore, we could show that the oriT we used can transport the plasmid on which is found in a very fast and efficient way, even between different strains. If the λ phage we genetically modified were able to lyse cells, we would have successfully completed our project!

The conjugation system may allow a broader application of our system in terms of species, since the RP-plasmids are broad host range plasmids and can therefore transfer genetic information to a variety of gram negative and gram positive bacteria. There is also evidence for conjugative transfer between bacteria and yeast cells [17]. If one could use this system to transfer genetic information into eukaryotic cells, this could be an application to cure plant diseases or even human diseases by injecting for example antisense RNA to silence viral replication or oncogenes. [back]

Acknowledgements

We would heartily like to extend our thanks to Prof. M. Bagdasarian from Michigan State University, to Prof. K. M. Derbyshire from Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health and Prof. E. Lanka from Bundesinstitute für Risikobewertung (BfR), Berlin for their precious and unconditional help by giving us a lot of information about conjugation and sending us the plasmids timely. They were all extremely helpful and even if in the end we couldn’t use all of their provided materials we profited from our correspondence to all of them.

We would also like to thank Dr. A. Trendl-Kern, Dr. P. Prior and Dr. W. Reiser at the Practical Laboratory, Zentrum für Molekularbiologie Heidelberg (ZMBH) for their aspiring support throughout our work, who shared their knowledge with us and provided us with different λ phages and materials.

We would also like to thank Sabine Aschenbrenner for helping us with technical assistance.

We can’t imagine realizing our project without their helps. Thank you very much!

References

[1] Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, de Crécy-Lagard V, Craig WA, Romesberg FE (2005). "Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance". PLoS Biol. 3 (6): e176

[2] N Chanishvili, T Chanishvili, M. Tediashvili, P.A. Barrow (2001). "Phages and their application against drug-resistant bacteria". J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol.) 76: 689–699

[3] Weber-Dabrowska B, Mulczyk M, Górski A (Jun 2003). "Bacteriophages as an efficient therapy for antibiotic-resistant septicemia in man". Transplant. Proc. 35 (4): 1385–6

[4] SWITCHES IN BACTERIOPHAGE LAMBDA DEVELOPMENT

Amos B. Oppenheim, Oren Kobiler, Joel Stavans, Donald L. Court, Sankar Adhya

Annual Review of Genetics, December 2005, Vol. 39, Pages 409-429

[5] Brussow, H. and Hendrix, R.W. 2002 "Small is beautiful.", Cell, 108, 13-16

[6] Dodd, J.B. Shearwin, K.E. and Egan, J.B. 2005 "Revisited gene regulation in phage lambda.", Curr Opin Genet Dev, 15, 145-152

[7] Friedman, D.I. and Court, D.L. 2001 "Bacteriophage lambda; alive and well and still doing its thing.", Current Opinion in Microbiology, 4, 201-207

[8] Court, D.L. et al. (2007): A new look at bacteriophage lambda genetic networks. In: J. Bacteriol. Bd. 189, 298-304

[9] Gottesman, M.E. & Weisberg, R.A. (2004): Little lambda, who made thee? In: Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. Bd. 68, S. 796-813

[10] Holmes RK, Jobling MG (1996). Genetics: Conjugation. in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al, eds.), 4th ed., Univ of Texas Medical Branch

[11] Introduction of DNA into Actinomycetes by bacterial conjugation from E. coli—An evaluation of various transfer systems, F. Blaesing, A. Mühlenweg, S. Vierling, G. Ziegelin, S. Pelzer, E. Lanka, Journal of Biotechnology 120 (2005) 146–161

[12] Lanka E, Wilkins BN (1995) DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu Rev Biochem 64:141-169

[13] Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncP a plasmids, E. Lanka et a., J. Mol. Biol., (1994), 239, 623-663

[14] Lessl M, Balzer D, Weyrauch K, Lanka E (1993) The mating pair formation system of plasmid RP4 desined by RSF1010 mobilization and donor speci®c phage propagation. J Bacteriol 175:6415-6425

[15] Target Choice and Orientation Preference of the Insertion Sequence IS903

Wen-Yuan Hu and Keith M. Derbyshire, J Bacteriol, June 1998, p. 3039-3048, Vol. 180, No. 12

[16] Transposition of TnA Does Not Generate Deletions, Peter M. Bennett, John Grinsted, Mark H. Richmond, Molec. gen. Genet. 154, 205-211 (1977)

[17] Lessl M, Lanka E (1994) Common mechanisms in bacterial conjugation and Ti-mediated T-DNA transfer to plant cells. Cell 77:1-20

[back]

"

"