Team:UC Berkeley/GatewayOverview

From 2008.igem.org

Why Use Gateway?

The first step of the layered assembly scheme involves the transfer of biobrick parts from an entry vector to a double antibiotic assembly vector. Traditionally, this would require a fairly work-intensive protocol requiring digestion, gel purification, ligation, transformation, and plasmid isolation. In addition to being more time-consuming, the aforementioned procedure is also suboptimal because it is difficult to scale-up.

The Gateway Cloning approach developed by [http://www.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/Products-and-Services/Applications/Cloning/Gateway-Cloning.html Invitrogen] offers a more efficient and convenient alternative for parts transfer. Their procedure involves the enzyme-catalyzed exchange of parts flanked by specific recombination sites. Experimentally, it is a one-pot, room-temperature reaction where the plasmids, buffer, water and enzymes are added together. After the addition of another enzyme and a short incubation period to terminate the reaction, the entire mixture can be transformed directly. This one-pot approach with a fewer steps is much more suitable for large-scale experimentation.

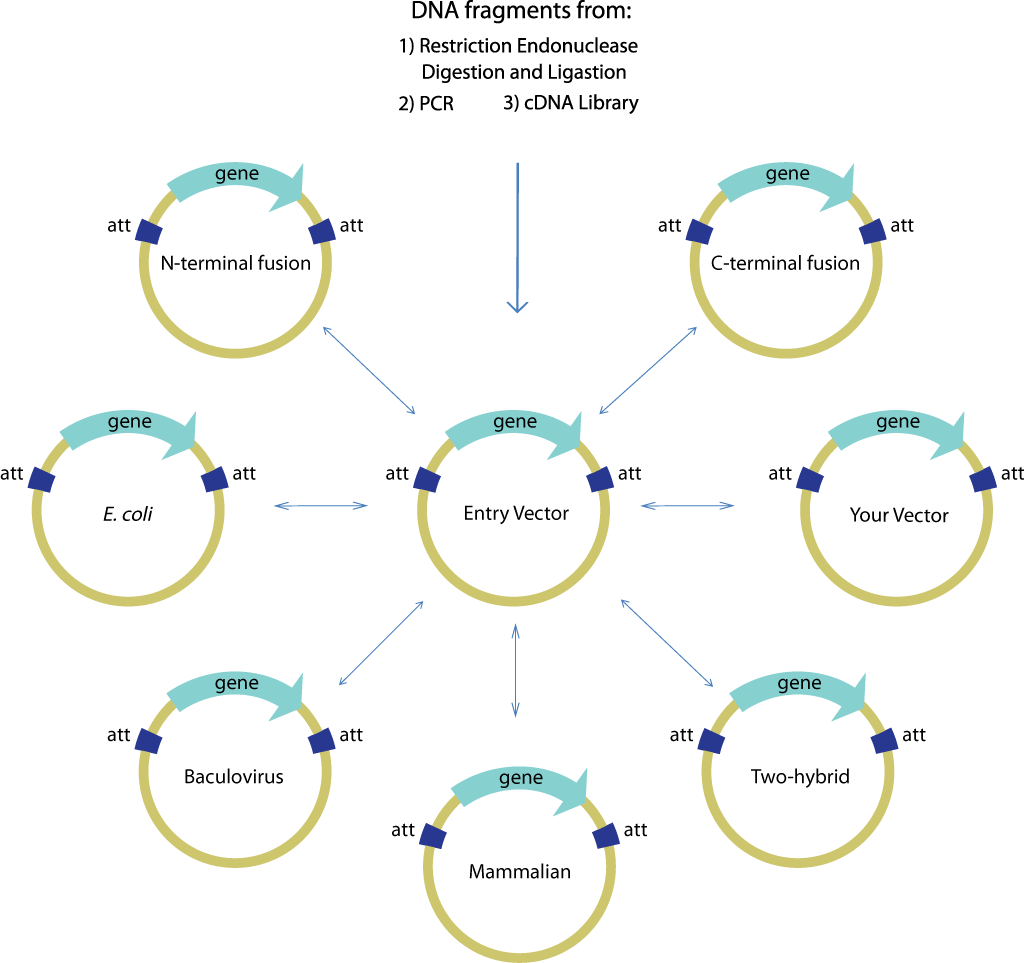

Gateway is commonly used to facilitate the transfer of a single gene of interest from an entry clone to multiple destination vectors, as shown below. The efficiency and robustness of the Gateway mechanism are ideal for this application because once the gene of interest is cloned and confirmed in the entry vector, subsequent transfers using Gateway need not be confirmed again. Thus, it is ideal for use in the first step of layered assembly where a part may be transferred to one or more of the double antibiotic vectors required for the subsequent assembly steps assembly.

Image source:https://commerce.invitrogen.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=iProtocol.unitSectionTree&treeNodeId=290D0521B5FFA1B782C62C0AB62FD7BC

Gateway Chemistry

The Natural Lambda Phage Recombination system

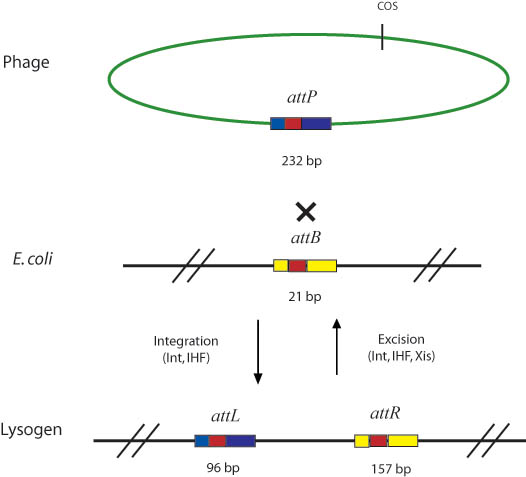

In general, Gateway reactions in the lab involve the attB, attP, attL, and attR recombination sites and the integrase (Int), excisionase (Xis), and integration host factor (IHF) enzymes. These enzymes were found in nature in the temperate bacteriophage lambda. Like all temperate bacteriophages, lambda utilizes a lysogenic infection life cycle, wherein its genome is incorporated into the genome of the E. coli host genome, to excise itself at a later time. Integrase (Int), excisionase (Xis), and integration host factor (IHF) are the enzymes that catalyze the integration and excision of the viral genome, at the previously mentioned att sites of the viral and host genomes.

Int cooperatively binds with IHF (which is composed of A and B subunits) in order to catalyze both the integration and excision reactions in the natural lambda phage system shown below. Although int can independently catalyze both reactions, IHF greatly improves int's binding affinity for the att recombination sites by bending the DNA [6]. Although int performs both the forward and reverse reactions, the equilibrium heavily favors the reaction of attB and attP to produce attL and attR sites. Xis binds to the attR sire and serves to shift the equilibrium so that it favors the reverse reaction [5].

Invitrogen's adaptation

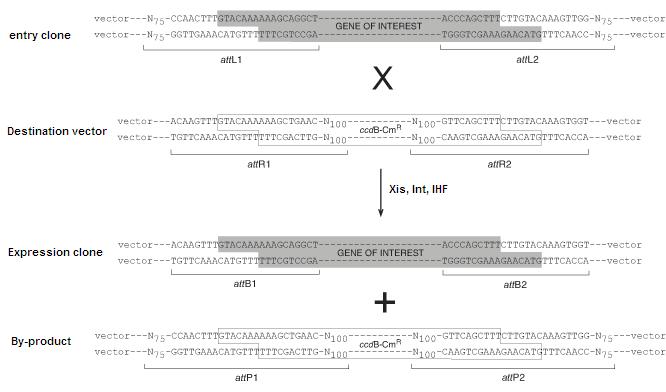

In the Invitrogen scheme, the recombination sites are found in pairs flanking sequences that are intended for transfer. The recombination pairs are directional and specificity is given by ten nucleotides in the core region of each site, as shown below. In addition, the lethal gene ccdB is incorporated in between the recombination sites in the destination vector to ensure that only the desired recombined product can be cloned.

Image source:https://commerce.invitrogen.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=iProtocol.unitSectionTree&treeNodeId=290D0521B5FFA1B782C62C0AB62FD7BC

The schematic below depicts the LR reaction, during which the attL sites recombine with attR to yield attB and attP sites. The BP reaction proceeds in the opposite direction yielding attL and attR sites.

Image source:https://commerce.invitrogen.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=iProtocol.unitSectionTree&treeNodeId=290D0521B5FFA1B782C62C0AB62FD7BC

Selection for Correct Clones

The above scheme employs both ccdB negative selection and antibiotic selection in order to yield >90% of colonies containing the desired expression clone. The entry and destination vectors contain different antibiotic resistances, so plating on the desired antibiotic (Ampicillin in case shown above) eliminates clones containing the entry vector or the by-product of the reaction. In addition, ccdB is a lethal gene, thereby eliminating colonies containing the destination vector, which would otherwise survive on the antibiotic plate.

Animation source: http://www.bio.davidson.edu/courses/Molbio/MolStudents/spring2000/patton/gateway.htm

Gateway in vivo

Plasmid Based Gateway

We applied our ideas for facilitating the automation of synthetic biology to the first step of layered assembly--the LR gateway reaction used to move the gene of interest into one or more of the double-antibiotic assembly vectors. We began by attempting to reproduce a plasmid based Gateway reaction, which was similar to that of Invitrogen's Gateway scheme. Although we were successful in having a completely in vivo version of the Gateway reaction, there were two major drawbacks: we had not eliminated the need for laborious and expensive mini-preps and we had relatively high background from ccdB mutations (the ccdB gene is relatively unstable because of its toxicity).

We addressed the first drawback by creating a self-lysis device which allows the cell's contents, including the desired product, to be released when arabinose is added. This device was inserted into either the entry or assembly plasmid to facilitate the isolation of the reaction products.

The second issue was more complex and was resolved by using positive selection methods rather than ccdB negative selection. Efforts to incorporate positive selection for Gateway led to the development of the Genomic Based Gateway scheme.

Genomic Based Gateway

The Genomic Based Gateway scheme involves placement of the assembly vector in the genome. The gene of interest from the entry vector can recombine with the genome to yield the desired product. Both the entry vector and assembly vector have conditional origins of replication which serve as mechanisms for positive selection. Although this is a viable scheme for Gateway and can readily incorporate the lysis device in place of mini-preps, it still requires transformation of the lysate in order to select for the desired product. In an effort to further optimize our Gateway scheme by eliminating the need for transformation, we developed a Phagemid Based Gateway scheme.

Phagemid Based Gateway

The Phagemid Based Gateway utilizes a plasmid that can be packaged in a phage when a lysogenic cell is induced with arabinose. The assembly vector in this scheme contains a phagemid device, which allows the product to be packaged and transferred to another cell without mini-preps or transformation. In addition to simplifying the transfer of the product, the phagemid device serves as a positive selection mechanism and can isolate the desired product when paired with another positive selector, such as an inducible origin of replication.

References

- http://tools.invitrogen.com/downloads/gateway-the-basics-seminar.html

- http://www.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/Products-and-Services/Applications/Cloning/Gateway-Cloning.html|Gateway

- https://commerce.invitrogen.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=iProtocol.unitSectionTree&treeNodeId=290D0521B5FFA1B782C62C0AB62FD7BC

- Cho, E et al. Interactions between Integrase and Excisionase in the Phage Lambda Excisive Nucleoprotein Complex. Journal of Bacteriology. September 2002; 184(18): 5200–5203. Available Online: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=135313 (Accessed: 28 October 2008).

- Frumerie, C et al. Cooperative interactions between bacteriophage P2 integrase and its accessory factors IHF and Cox. Virology. 5 February 2005; 232(1):284-294. Available Online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WXR-4F29SN2-1&_user=4420&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=4420&md5=0f9e41ba422140f157a2b1f1fb60b140 (Accessed: 28 October 2008).

"

"