Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory

From 2008.igem.org

(New page: {{:Team:KULeuven/Tools/Navigation_Bar}} == [https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/0/05/Memory.zip Memory] == Memory) |

m |

||

| (134 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | {{:Team:KULeuven/Tools/ | + | {{:Team:KULeuven/Tools/Styling}} |

| + | {{:Team:KULeuven/Tools/Scripting}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:KULeuven/Tools/Header}} | ||

| - | + | [[Image:pictogram_memory.png|120px|right]] | |

| - | [[Image:Memory.png| | + | == Memory == |

| + | |||

| + | === Position in the system === | ||

| + | |||

| + | This system must activate the cell death system after one light pulse. As long as there is no light, there is no P2ogr, no CIIP22 and a lot of antimRNA_LuxI. The antimRNA_LuxI blocks the cell death system. When light is turned on OmpF increases. This causes P2ogr and CIIP22 to increase and antimRNA_LuxI to decrease. This activates the system. When light is turned off, the P2ogr concentration is large enough to maintain itself. This way antimRNA doesn't increase. The system stays activated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Describing the system === | ||

| + | |||

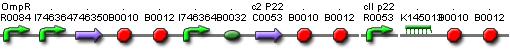

| + | [[Image:Memory_BioBrick.jpg|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== ODE's ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Parameters ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| width=80% style="border: 1px solid #003E81; background-color: #EEFFFF;" | ||

| + | |+ ''Parameter values (Memory)'' | ||

| + | ! width=15% | Name | ||

| + | ! width=15% | Value | ||

| + | ! width=40% | Comments | ||

| + | ! width=10% | Reference | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Degradation Rates | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>P2ogr</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.002265 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [1<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>RNA_P2ogr</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.002265 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [2<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>P22CII</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.002311 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | This value is too low. The correct value is used in the final model. | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>RNA_P22CII</sub> | ||

| + | | 0,0022651 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [2<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>antimRNA_luxI</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0045303 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [2<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Transcription Rates | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>P2ogr</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0125 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [4<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>P22CII</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0125 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [4<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>AntimRNA_LuxI</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0094 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [5<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Dissociation Constants | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | K<sub>P2ogr</sub> | ||

| + | | 4.2156 | ||

| + | | Used in two reactions for activator control at the transcription of P2ogr mRNA and CIIP22 mRNA | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [6<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | K<sub>R0053_P22CII</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.1099 | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Hill Cooperativity | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | n<sub></sub> | ||

| + | | 2 | ||

| + | | Used for all reactions throughout the memory submodel using Hill kinetics | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [1<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Models === | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== CellDesigner ([https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/4/49/Memory_CellDesigner.zip SBML file])==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Memory.png|600px|center|Memory]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Matlab ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Problem === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The OmpF promoter is not ideal. When there is no light the transcription rate is still 0.00005 s<sup>-1</sup>. This means that P2ogr will slowly build up, activating the system. In this case the memory is in 0-state when the stationary state isn't reached yet. The 1-state is the stationary state. So the system automatically ends up in state 1 after some time (300s). This can be seen in the figure below. | ||

| + | [[Image:mem_no_act.png|600px|center|mem_no_act]] | ||

| + | ::: '''Figure: CIIP22(purple), P2ogr(green), AntimRNA(pink). | ||

| + | The system can only stay in 0-state for 300 sec. This makes it completely useless. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Alternative === | ||

| + | In the previous system the 0-state isn't actively maintained. It's just 'not stationary state'. So we need to search mathematical system that has 2 stationary states. A possible solution is given below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Alt.png|500px|center|alt]] | ||

| + | ::::'''Figure: Part representation of alternative system''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | When this system starts Rep build up because Rep represses the Act promoter better then Act represses the Rep promoter. The Rep concentration stays high and the Act stays low. This is the 0-state. When there is light, the OmpF promoter is activated and the Act concentration is increased. This represses Rep promoter. The Rep concentration decreases and the Act promoter is activated. The Act concentration keeps increasing. When the light pulse ends the Act concentration is high enough to repress the Rep promoter, Act concentration stays high and Rep concentration stays low. This is the 1-state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | CellDesigner gives the following simulation when OmpF transcription rate changes from 0.0001 to 0.01 at t=6000 sec for 2000 sec. | ||

| + | [[Image:alt_CDplot.png|600px|center|alt_CDplot]] | ||

| + | :::'''Figure: Celldesigner simulation of the alterative system. Act(grey), Rep(yellow) ''' | ||

| + | The OmpF peak causes the Act concentration to rise and the Rep to decrease. The high Act concentration keeps the Rep concentration low. This causes the Act concentration to stay high. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === References === | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en"> | ||

| + | <head> | ||

| + | <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8"/> | ||

| + | <title>Bibliography</title> | ||

| + | </head> | ||

| + | <body> | ||

| + | <table style="border-collapse:collapse;line-height:1.1em;"> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[1]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“ETHZ/Parameters - IGEM07”; https://2007.igem.org/ETHZ/Parameters.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[2]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">J.A. Bernstein et al., “Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays,” <span style="font-style:italic;">Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America</span>, vol. 99, Jul. 2002, pp. 9697–9702. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Adoi/10.1073/pnas.112318199&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Global%20analysis%20of%20mRNA%20decay%20and%20abundance%20in%20Escherichia%20coli%20at%20single-gene%20resolution%20using%20two-color%20fluorescent%20DNA%20microarrays&rft.jtitle=Proceedings%20of%20the%20National%20Academy%20of%20Sciences%20of%20the%20United%20States%20of%20America&rft.stitle=Proc%20Natl%20Acad%20Sci%20U%20S%20A.%20&rft.volume=99&rft.issue=15&rft.aufirst=Jonathan%20A.&rft.aulast=Bernstein&rft.au=Jonathan%20A.%20Bernstein&rft.au=Arkady%20B.%20Khodursky&rft.au=Pei-Hsun%20Lin&rft.au=Sue%20Lin-Chao&rft.au=Stanley%20N.%20Cohen&rft.date=2002-07-23&rft.pages=9697%E2%80%939702"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[3]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">J. De Anda, A. Poteete, and R. Sauer, “P22 c2 repressor. Domain structure and function,” <span style="font-style:italic;">J. Biol. Chem.</span>, vol. 258, Sep. 1983, pp. 10536-10542. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=P22%20c2%20repressor.%20Domain%20structure%20and%20function&rft.jtitle=J.%20Biol.%20Chem.&rft.volume=258&rft.issue=17&rft.aufirst=J&rft.aulast=De%20Anda&rft.au=J%20De%20Anda&rft.au=AR%20Poteete&rft.au=RT%20Sauer&rft.date=1983-09-10&rft.pages=10536-10542"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[4]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa I746364 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746364.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[5]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa R0053 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0053.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[6]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">D. Kornitzer, S. Altuvia, and A.B. Oppenheim, “The activity of the CIII regulator of lambdoid bacteriophages resides within a 24-amino acid protein domain.,” <span style="font-style:italic;">Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America</span>, vol. 88, Jun. 1991, pp. 5217–5221. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=The%20activity%20of%20the%20CIII%20regulator%20of%20lambdoid%20bacteriophages%20resides%20within%20a%2024-amino%20acid%20protein%20domain.&rft.jtitle=Proceedings%20of%20the%20National%20Academy%20of%20Sciences%20of%20the%20United%20States%20of%20America&rft.stitle=Proc%20Natl%20Acad%20Sci%20U%20S%20A.%20&rft.volume=88&rft.issue=12&rft.aufirst=D.&rft.aulast=Kornitzer&rft.au=D.%20Kornitzer&rft.au=S.%20Altuvia&rft.au=A%20B%20Oppenheim&rft.date=1991-06-15&rft.pages=5217%E2%80%935221"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | </table></body> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Memory - episode 2== | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Position in the system === | ||

| + | |||

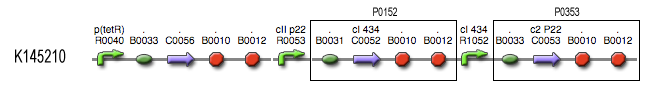

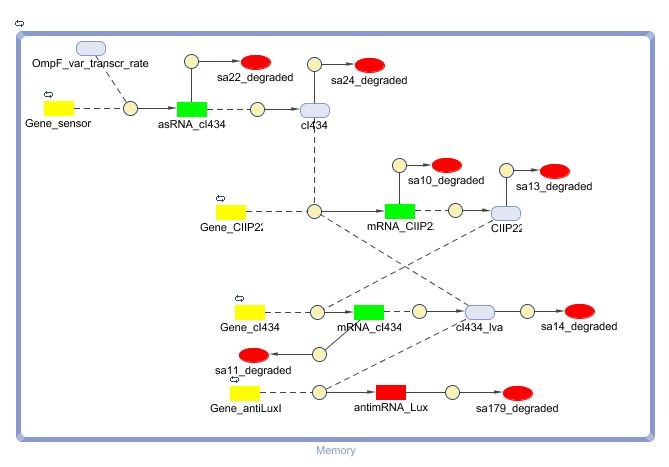

| + | The Memory must keep the [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Cell_Death Cell Death] inactivated untill a decent input signal has been received. When there is no input signal, c2 P22 will take control and repress cI 434 and [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Cell_Death Cell Death]. This is the OFF state in which the memory can remain indefinitely unless an input signal emerges. This causes production of cI 434 (without LVA tag) whih will repress c2 P22 production, allowing cI 434 production to start from the c2 P22 repressible promoter. cI 434 will also start repressing the antisense LuxI production, enabling the [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Inverter InverTimer] to do its work. After an input signal of about 1000 seconds, enough of the c2 P22 has disappeared in order to make the cI 434 production (LVA) self-sufficient. At this point, the memory has reached the ON state in which it will remain. For a more elaborate description of the Memory's biomolecular workings, please see the [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Project/Memory Project/Memory] page. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Describing the system === | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Alt2.png|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is the same figure as the alternative, but this time filled in for the new system. It conventiently shows that the system is based upon the alternative suggested above while laying out the workings and concretisations in the form of the different BioBricks implemented. Rep is now the c2 P22 repressor while Act is represented by cI 434. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:New_Mem_symbols.PNG|center]] | ||

| + | [[Image:New_Mem_symbols_output.PNG|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The output of this system is antisense RNA production that represses the LuxI translation. c2 P22 has also got a function in repressing [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Cell_Death Cell Death] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====ODE's==== | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <body> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/4/4c/MemoryODE.pdf"> | ||

| + | <img border="0" src="https://2008.igem.org/wiki/skins/common/images/icons/fileicon-pdf.png" width="65" height="60"> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </body> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Parameters ==== | ||

| + | {| width=80% style="border: 1px solid #003E81; background-color: #EEFFFF;" | ||

| + | |+ ''Parameter values (New Memory)'' | ||

| + | ! width=15% | Name | ||

| + | ! width=15% | Value | ||

| + | ! width=40% | Comments | ||

| + | ! width=10% | Reference | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Degradation Rates | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>cIIP22</sub> | ||

| + | | d<sub>LVA</sub> = 2.814E-4 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | LVA-tag reduces lifetime to 40 minutes | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [5<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>mRNA_cIIP22</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0023104906 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>cI434_LVA</sub> | ||

| + | | d<sub>LVA</sub> = 2.814E-4 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | LVA-tag reduces lifetime to 40 minutes | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [5<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>mRNA_cI434_LVA</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0023104906 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>cI434</sub> | ||

| + | | 9.627044174E-5 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | no LVA tag, so longer lifetime (t<sub>1/2</sub> = 2h) | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>mRNA_cI434</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0023104906 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>asRNA luxI</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.00462 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | d<sub>LuxI asRNA complex</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.00462 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [3<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | c2 P22 transcription (cI 434 regulated) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>transcr</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0125 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate of maximal transcription rate, strong promoter | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [10<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | K<sub>m</sub> (cI 434) | ||

| + | | 0.8708 | ||

| + | | Recalculated to remove [M] dimension from K<sub>m</sub>=2E-9 [M] | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [12<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | cI 434 transcription (c2 P22 regulated) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>transcr</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0040 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | estimate of maximal transcription rate, weak-medium promoter | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [11<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | K<sub>m</sub> (c2 P22) | ||

| + | | 0.1099 | ||

| + | | Recalculated to remove [M]<sup>2</sup> dimension from K<sub>app</sub>=6.8E-20[M]<sup>2</sup> | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [6<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | TetR regulated promoter | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | TetR_var_transcr_rate | ||

| + | | p(TetR) dependent | ||

| + | | (RiboKey) between 5E-5 and 0.0125 s<sup>-1</sup> ~ [aTc] | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [4<html>]</html> [9<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Translation rates | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>transl_cI434</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0055555 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | translation rate for B0033 RBS (0.01 relative efficiency) | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [8<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>transl_cI434_lva</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0388889 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | translation rate for B0031 RBS (0.07 relative efficiency) | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [7<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k<sub>transl_cIIP22</sub> | ||

| + | | 0.0055555 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | translation rate for B0033 RBS (0.01 relative efficiency) | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [8<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Hill Cooperativity | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | n<sub></sub> | ||

| + | | 2 | ||

| + | | Used for all reactions throughout the memory submodel using Hill kinetics | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [2<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="4" style="border-bottom: 1px solid #003E81;" | Antisense LuxI | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | k_complex3 | ||

| + | | 0.00237 s<sup>-1</sup> | ||

| + | | rate constant for formation of asRNA - LuxI mRNA duplex | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [1<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | K<sub>mRNA_LuxI:antisense_mRNA</sub> | ||

| + | | 4.22E-14 [M] | ||

| + | | Dissociation constant for complex of LuxI mRNA with antisense mRNA | ||

| + | | [https://2008.igem.org/Team:KULeuven/Model/Memory#References [1<html>]</html>] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Models=== | ||

| + | ==== CellDesigner([https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/4/49/Memory_CellDesigner.zip SBML file])==== | ||

| + | [[Image:Memory_CellDesigner.png|600px|center|New Memory]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Matlab ([https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/1/1f/Memory_Matlab.zip SBML file])==== | ||

| + | [[Image:Memory_Matlab.jpg|600px|center|New Memory]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Simulations === | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Multiple simulations have been performed to see if the memory works. If we give a pulse of TetR from | ||

| + | 5E-5 to 0.0125 for 10000 sec, we see that the memory switches from its 0-state to its 1-state (left figure): | ||

| + | cIIP22 amount drops and the cI434 increases. The high cI434 amount will repress the RNA production. If the | ||

| + | pulse lasts for only 1000 sec, the memory remains in its 0-state (middle figure). Simulations show the | ||

| + | minimum time span needed to switch the memory is approximately 1300 sec. The right figure shows us that a sequence | ||

| + | of two pulses of only 1000 sec can also make the memory switch. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The graphs have amounts (number of molecules in the cell) plotted vs time, measured in seconds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <div class="noborder" style="overflow: auto; width: 800px; height: 420px;"> | ||

| + | <div class="noborder" style="width: 1250px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/8/80/Memory1.png" style="float: left; width: 400px; height: 400px; margin: 0 5px;" /> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/3/37/Memory2.png" style="float: left; width: 400px; height: 400px; margin: 0 5px;" /> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/b/bf/Memory3.png" style="float: left; width: 400px; height: 400px; margin: 0 5px;" /> | ||

| + | </div></div></div></html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Mathematical Analysis ([https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/8/87/Memory_Maple.zip Maple file])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The existence of the two stable states of the memory (cI434_LVA high and cIIP22 low / cI434_LVA low and cIIP22 high) can be mathematically proven. | ||

| + | |||

| + | First we define the equilibrium points of the following differential equation system: | ||

| + | [[Image:Differential.png|700px|center]] | ||

| + | The equilibrium points are defined as the points for which all the derivatives are zero. Solving this non-linear system for [OmpF] equal to 0.00005 results in finding the roots of the equation | ||

| + | [[Image:Equation.png|600px|center]] | ||

| + | This equation has three real zeros ([CI434_LVA = 0.002435815407], [CI434_LVA = 11.52604711], [CI434_LVA = 233.6410112]) and two conjugated imaginary zeros ([CI434_LVA = -8.242012862+11.11131953*I], [CI434_LVA = -8.242012862-11.11131953*I]) as can be seen in the following figure: | ||

| + | [[Image:Equation.jpg|300px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The real roots of the system for all the variables are: | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | ||

| + | |+Real Roots | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! !! Zero 1 !! Zero 2 !! Zero 3 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [CI434] | ||

| + | | 1.248827120|| 1.248827120|| 1.248827120 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [CI434-LVA] | ||

| + | | 0.002435815407|| 11.52604711|| 233.6410112 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [mRNA<sub>CI434-LVA</sub>] | ||

| + | | 0.00001804584283|| 0.08539121399|| 1.730939445 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [CIIP22] | ||

| + | | 34.03962262|| 0.4824866257 || 0.001433763049 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [mRNA<sub>CIIP22</sub>] | ||

| + | | 1.765288021 || 0.02502165991 || 0.00007435466497 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! [asRNA<sub>CI434</sub>] | ||

| + | | 0.02164042563 || 0.02164042563 || 0.02164042563 | ||

| + | |} | ||

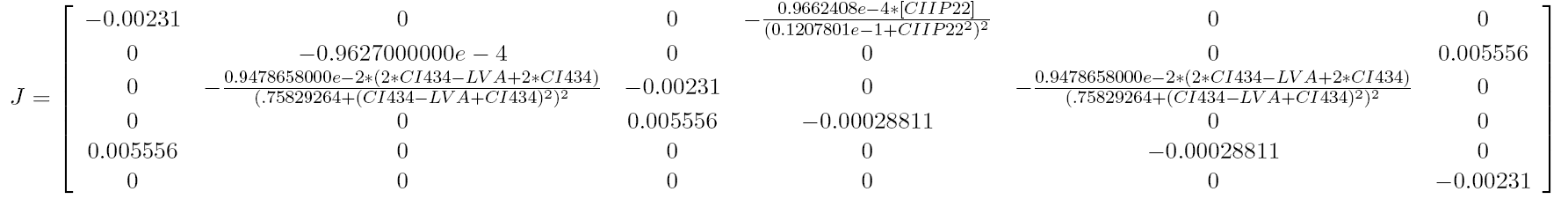

| + | The stability of the three real zeros is defined by the eigenvalues of the Jacobian of the differential equation system. This Jacobian equals | ||

| + | [[Image:Jacobian.png|800px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

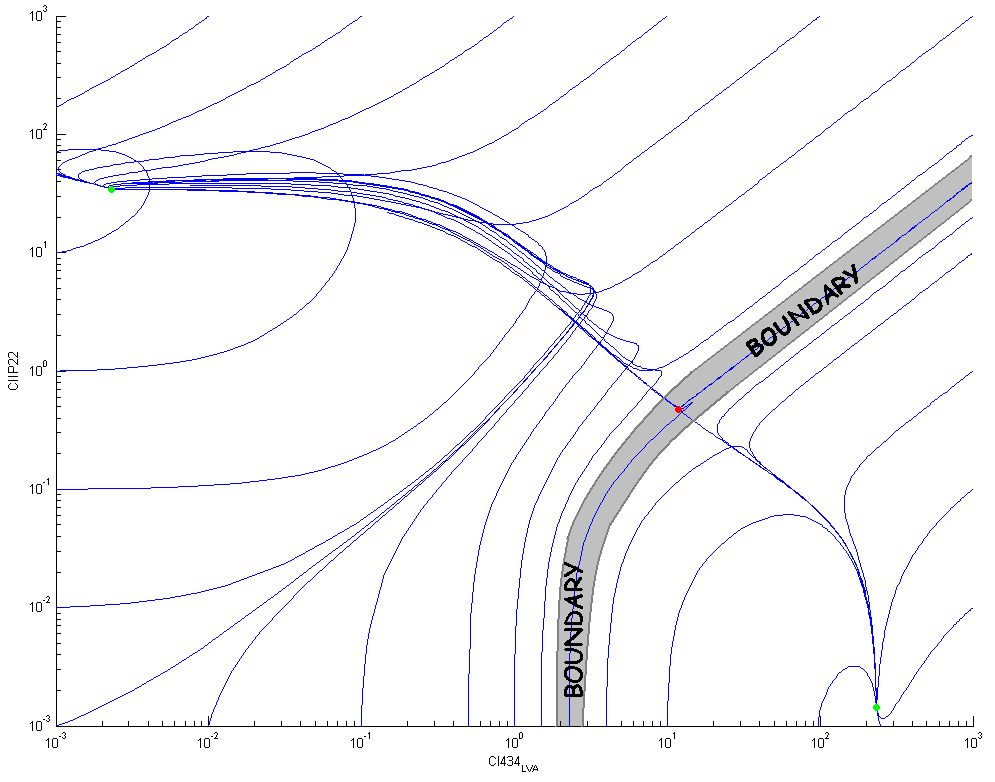

| + | The eigenvalues for '''Zero 1''' are all negative (-0.2334056227e-2, -0.2286362516e-2, -0.3122380843e-3, -0.2645443732e-3, -0.9627000000e-4, -0.2310490600e-2). This is also the case for '''Zero 3''' (-0.2319019326e-2, -0.2301889325e-2, -0.2795812737e-3, -0.2967112750e-3, -0.9627000000e-4, -0.2310490600e-2). These two zero's represent the two stable states of the memory system. '''Zero 2''' has one positive eigenvalue (0.0002015903724) and is therefore unstable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following figure shows some trajectories in the phase plane ([CIIP22],[CI434-LVA]): there is a clear boundary between the two stable equilibrium points (the green dots) that goes through the unstable equilibrium point (the red dot). This boundary divides the two dimensional phase plane in two separate basins of attraction. | ||

| + | [[Image:Memory_PhasePlot.png|600px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === References === | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en"> | ||

| + | <head> | ||

| + | <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8"/> | ||

| + | <title>Bibliography</title> | ||

| + | </head> | ||

| + | <body> | ||

| + | <table style="border-collapse:collapse;line-height:1.1em;"> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[1]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">A. E G H Wagner and R W Simons, “Antisense RNA Control in Bacteria, Phages, and Plasmids,” Nov. 2003; http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003433.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[2]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“ETHZ/Parameters - IGEM07”; https://2007.igem.org/ETHZ/Parameters.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[3]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">J.A. Bernstein et al., “Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays,” <span style="font-style:italic;">Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America</span>, vol. 99, Jul. 2002, pp. 9697–9702. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Adoi/10.1073/pnas.112318199&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Global%20analysis%20of%20mRNA%20decay%20and%20abundance%20in%20Escherichia%20coli%20at%20single-gene%20resolution%20using%20two-color%20fluorescent%20DNA%20microarrays&rft.jtitle=Proceedings%20of%20the%20National%20Academy%20of%20Sciences%20of%20the%20United%20States%20of%20America&rft.stitle=Proc%20Natl%20Acad%20Sci%20U%20S%20A.%20&rft.volume=99&rft.issue=15&rft.aufirst=Jonathan%20A.&rft.aulast=Bernstein&rft.au=Jonathan%20A.%20Bernstein&rft.au=Arkady%20B.%20Khodursky&rft.au=Pei-Hsun%20Lin&rft.au=Sue%20Lin-Chao&rft.au=Stanley%20N.%20Cohen&rft.date=2002-07-23&rft.pages=9697%E2%80%939702"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[4]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">M. Bon, S.J. McGowan, and P.R. Cook, “Many expressed genes in bacteria and yeast are transcribed only once per cell cycle,” <span style="font-style:italic;">FASEB J.</span>, vol. 20, Aug. 2006, pp. 1721-1723. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Adoi/10.1096/fj.06-6087fje&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Many%20expressed%20genes%20in%20bacteria%20and%20yeast%20are%20transcribed%20only%20once%20per%20cell%20cycle&rft.jtitle=FASEB%20J.&rft.volume=20&rft.issue=10&rft.aufirst=Michael&rft.aulast=Bon&rft.au=Michael%20Bon&rft.au=Simon%20J.%20McGowan&rft.au=Peter%20R.%20Cook&rft.date=2006-08-01&rft.pages=1721-1723"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[5]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">J.B. Andersen et al., “New Unstable Variants of Green Fluorescent Protein for Studies of Transient Gene Expression in Bacteria,” <span style="font-style:italic;">Applied and Environmental Microbiology</span>, vol. 64, Jun. 1998, pp. 2240–2246. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=New%20Unstable%20Variants%20of%20Green%20Fluorescent%20Protein%20for%20Studies%20of%20Transient%20Gene%20Expression%20in%20Bacteria&rft.jtitle=Applied%20and%20Environmental%20Microbiology&rft.stitle=Appl%20Environ%20Microbiol.%20&rft.volume=64&rft.issue=6&rft.aufirst=Jens%20Bo&rft.aulast=Andersen&rft.au=Jens%20Bo%20Andersen&rft.au=Claus%20Sternberg&rft.au=Lars%20Kongsbak%20Poulsen&rft.au=Sara%20Petersen%20Bj%C3%B8rn&rft.au=Michael%20Givskov&rft.au=S%C3%B8ren%20Molin&rft.date=1998-06&rft.pages=2240%E2%80%932246"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[6]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">J. De Anda, A. Poteete, and R. Sauer, “P22 c2 repressor. Domain structure and function,” <span style="font-style:italic;">J. Biol. Chem.</span>, vol. 258, Sep. 1983, pp. 10536-10542. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=P22%20c2%20repressor.%20Domain%20structure%20and%20function&rft.jtitle=J.%20Biol.%20Chem.&rft.volume=258&rft.issue=17&rft.aufirst=J&rft.aulast=De%20Anda&rft.au=J%20De%20Anda&rft.au=AR%20Poteete&rft.au=RT%20Sauer&rft.date=1983-09-10&rft.pages=10536-10542"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[7]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa B0031 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_B0031.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[8]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa B0033 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0033.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[9]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa R0040 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040.</td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[10]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa R0052 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0052.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[11]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">“Part:BBa R0053 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0053.</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr style="vertical-align:top;"><td>[12]</td><td style="padding-left:4pt;">B.C. McCabe, D.R. Pawlowski, and G.B. Koudelka, “The Bacteriophage 434 Repressor Dimer Preferentially Undergoes Autoproteolysis by an Intramolecular Mechanism,” <span style="font-style:italic;">J. Bacteriol.</span>, vol. 187, Aug. 2005, pp. 5624-5630. <span class="Z3988" title="url_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Adoi/10.1128/JB.187.16.5624-5630.2005&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=The%20Bacteriophage%20434%20Repressor%20Dimer%20Preferentially%20Undergoes%20Autoproteolysis%20by%20an%20Intramolecular%20Mechanism&rft.jtitle=J.%20Bacteriol.&rft.volume=187&rft.issue=16&rft.aufirst=Barbara%20C.&rft.aulast=McCabe&rft.au=Barbara%20C.%20McCabe&rft.au=David%20R.%20Pawlowski&rft.au=Gerald%20B.%20Koudelka&rft.date=2005-08-15&rft.pages=5624-5630"></span></td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td colspan="2"> </td></tr> | ||

| + | </table></body> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 23:24, 29 October 2008

Contents |

Memory

Position in the system

This system must activate the cell death system after one light pulse. As long as there is no light, there is no P2ogr, no CIIP22 and a lot of antimRNA_LuxI. The antimRNA_LuxI blocks the cell death system. When light is turned on OmpF increases. This causes P2ogr and CIIP22 to increase and antimRNA_LuxI to decrease. This activates the system. When light is turned off, the P2ogr concentration is large enough to maintain itself. This way antimRNA doesn't increase. The system stays activated.

Describing the system

ODE's

Parameters

| Name | Value | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degradation Rates | |||

| dP2ogr | 0.002265 s-1 | [1] | |

| dRNA_P2ogr | 0.002265 s-1 | [2] | |

| dP22CII | 0.002311 s-1 | This value is too low. The correct value is used in the final model. | [3] |

| dRNA_P22CII | 0,0022651 s-1 | [2] | |

| dantimRNA_luxI | 0.0045303 s-1 | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | [2] |

| Transcription Rates | |||

| kP2ogr | 0.0125 s-1 | estimate | [4] |

| kP22CII | 0.0125 s-1 | estimate | [4] |

| kAntimRNA_LuxI | 0.0094 s-1 | estimate | [5] |

| Dissociation Constants | |||

| KP2ogr | 4.2156 | Used in two reactions for activator control at the transcription of P2ogr mRNA and CIIP22 mRNA | [6] |

| KR0053_P22CII | 0.1099 | [3] | |

| Hill Cooperativity | |||

| n | 2 | Used for all reactions throughout the memory submodel using Hill kinetics | [1] |

Models

CellDesigner (SBML file)

Matlab

Problem

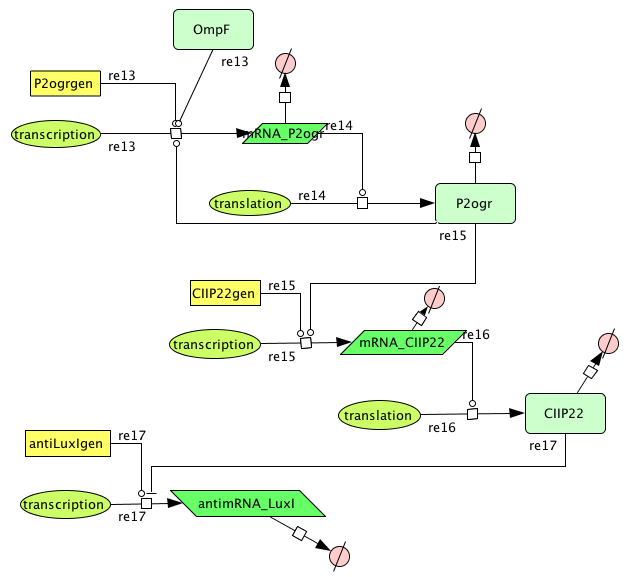

The OmpF promoter is not ideal. When there is no light the transcription rate is still 0.00005 s-1. This means that P2ogr will slowly build up, activating the system. In this case the memory is in 0-state when the stationary state isn't reached yet. The 1-state is the stationary state. So the system automatically ends up in state 1 after some time (300s). This can be seen in the figure below.

- Figure: CIIP22(purple), P2ogr(green), AntimRNA(pink).

The system can only stay in 0-state for 300 sec. This makes it completely useless.

Alternative

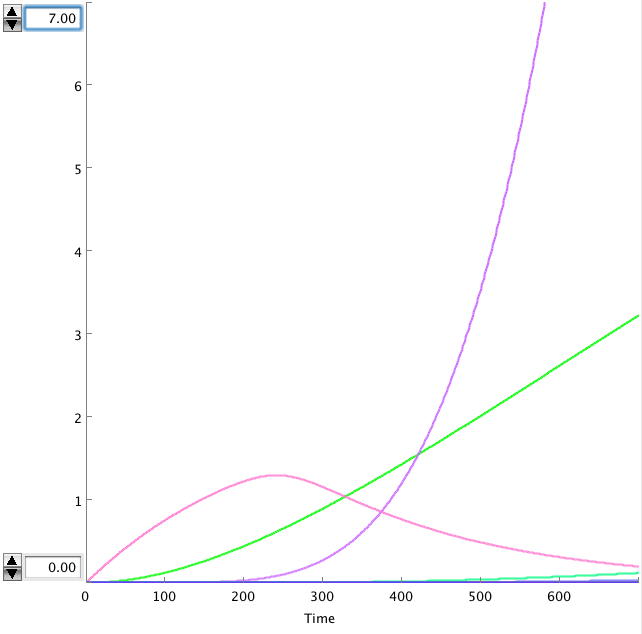

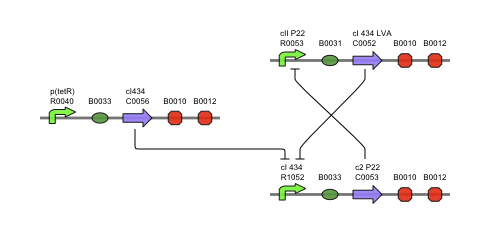

In the previous system the 0-state isn't actively maintained. It's just 'not stationary state'. So we need to search mathematical system that has 2 stationary states. A possible solution is given below.

- Figure: Part representation of alternative system

When this system starts Rep build up because Rep represses the Act promoter better then Act represses the Rep promoter. The Rep concentration stays high and the Act stays low. This is the 0-state. When there is light, the OmpF promoter is activated and the Act concentration is increased. This represses Rep promoter. The Rep concentration decreases and the Act promoter is activated. The Act concentration keeps increasing. When the light pulse ends the Act concentration is high enough to repress the Rep promoter, Act concentration stays high and Rep concentration stays low. This is the 1-state.

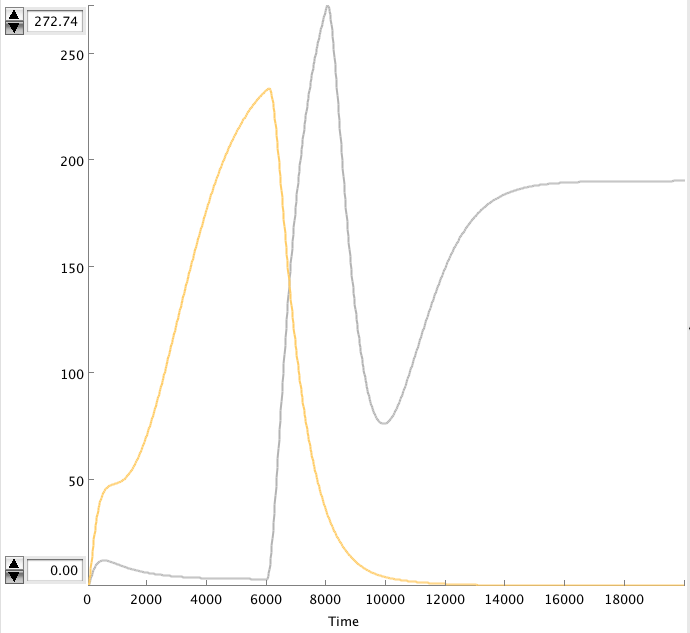

CellDesigner gives the following simulation when OmpF transcription rate changes from 0.0001 to 0.01 at t=6000 sec for 2000 sec.

- Figure: Celldesigner simulation of the alterative system. Act(grey), Rep(yellow)

The OmpF peak causes the Act concentration to rise and the Rep to decrease. The high Act concentration keeps the Rep concentration low. This causes the Act concentration to stay high.

References

| [1] | “ETHZ/Parameters - IGEM07”; https://2007.igem.org/ETHZ/Parameters. |

| [2] | J.A. Bernstein et al., “Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 99, Jul. 2002, pp. 9697–9702. |

| [3] | J. De Anda, A. Poteete, and R. Sauer, “P22 c2 repressor. Domain structure and function,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 258, Sep. 1983, pp. 10536-10542. |

| [4] | “Part:BBa I746364 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746364. |

| [5] | “Part:BBa R0053 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0053. |

| [6] | D. Kornitzer, S. Altuvia, and A.B. Oppenheim, “The activity of the CIII regulator of lambdoid bacteriophages resides within a 24-amino acid protein domain.,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 88, Jun. 1991, pp. 5217–5221. |

Memory - episode 2

Position in the system

The Memory must keep the Cell Death inactivated untill a decent input signal has been received. When there is no input signal, c2 P22 will take control and repress cI 434 and Cell Death. This is the OFF state in which the memory can remain indefinitely unless an input signal emerges. This causes production of cI 434 (without LVA tag) whih will repress c2 P22 production, allowing cI 434 production to start from the c2 P22 repressible promoter. cI 434 will also start repressing the antisense LuxI production, enabling the InverTimer to do its work. After an input signal of about 1000 seconds, enough of the c2 P22 has disappeared in order to make the cI 434 production (LVA) self-sufficient. At this point, the memory has reached the ON state in which it will remain. For a more elaborate description of the Memory's biomolecular workings, please see the Project/Memory page.

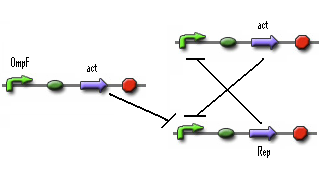

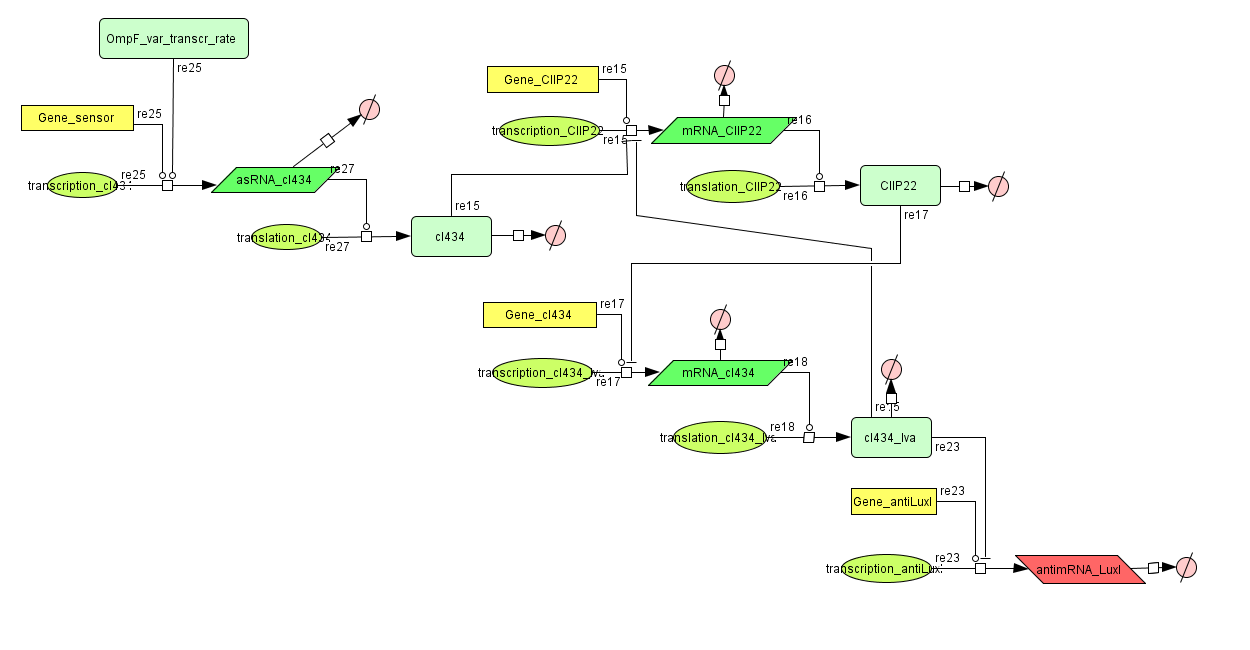

Describing the system

This is the same figure as the alternative, but this time filled in for the new system. It conventiently shows that the system is based upon the alternative suggested above while laying out the workings and concretisations in the form of the different BioBricks implemented. Rep is now the c2 P22 repressor while Act is represented by cI 434.

The output of this system is antisense RNA production that represses the LuxI translation. c2 P22 has also got a function in repressing Cell Death

ODE's

Parameters

| Name | Value | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degradation Rates | |||

| dcIIP22 | dLVA = 2.814E-4 s-1 | LVA-tag reduces lifetime to 40 minutes | [5] |

| dmRNA_cIIP22 | 0.0023104906 s-1 | [3] | |

| dcI434_LVA | dLVA = 2.814E-4 s-1 | LVA-tag reduces lifetime to 40 minutes | [5] |

| dmRNA_cI434_LVA | 0.0023104906 s-1 | [3] | |

| dcI434 | 9.627044174E-5 s-1 | no LVA tag, so longer lifetime (t1/2 = 2h) | |

| dmRNA_cI434 | 0.0023104906 s-1 | [3] | |

| dasRNA luxI | 0.00462 s-1 | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | [3] |

| dLuxI asRNA complex | 0.00462 s-1 | estimate: because this RNA isn't translated, it degrades faster | [3] |

| c2 P22 transcription (cI 434 regulated) | |||

| ktranscr | 0.0125 s-1 | estimate of maximal transcription rate, strong promoter | [10] |

| Km (cI 434) | 0.8708 | Recalculated to remove [M] dimension from Km=2E-9 [M] | [12] |

| cI 434 transcription (c2 P22 regulated) | |||

| ktranscr | 0.0040 s-1 | estimate of maximal transcription rate, weak-medium promoter | [11] |

| Km (c2 P22) | 0.1099 | Recalculated to remove [M]2 dimension from Kapp=6.8E-20[M]2 | [6] |

| TetR regulated promoter | |||

| TetR_var_transcr_rate | p(TetR) dependent | (RiboKey) between 5E-5 and 0.0125 s-1 ~ [aTc] | [4] [9] |

| Translation rates | |||

| ktransl_cI434 | 0.0055555 s-1 | translation rate for B0033 RBS (0.01 relative efficiency) | [8] |

| ktransl_cI434_lva | 0.0388889 s-1 | translation rate for B0031 RBS (0.07 relative efficiency) | [7] |

| ktransl_cIIP22 | 0.0055555 s-1 | translation rate for B0033 RBS (0.01 relative efficiency) | [8] |

| Hill Cooperativity | |||

| n | 2 | Used for all reactions throughout the memory submodel using Hill kinetics | [2] |

| Antisense LuxI | |||

| k_complex3 | 0.00237 s-1 | rate constant for formation of asRNA - LuxI mRNA duplex | [1] |

| KmRNA_LuxI:antisense_mRNA | 4.22E-14 [M] | Dissociation constant for complex of LuxI mRNA with antisense mRNA | [1] |

Models

CellDesigner(SBML file)

Matlab (SBML file)

Simulations

Multiple simulations have been performed to see if the memory works. If we give a pulse of TetR from 5E-5 to 0.0125 for 10000 sec, we see that the memory switches from its 0-state to its 1-state (left figure): cIIP22 amount drops and the cI434 increases. The high cI434 amount will repress the RNA production. If the pulse lasts for only 1000 sec, the memory remains in its 0-state (middle figure). Simulations show the minimum time span needed to switch the memory is approximately 1300 sec. The right figure shows us that a sequence of two pulses of only 1000 sec can also make the memory switch.

The graphs have amounts (number of molecules in the cell) plotted vs time, measured in seconds.

Mathematical Analysis (Maple file)

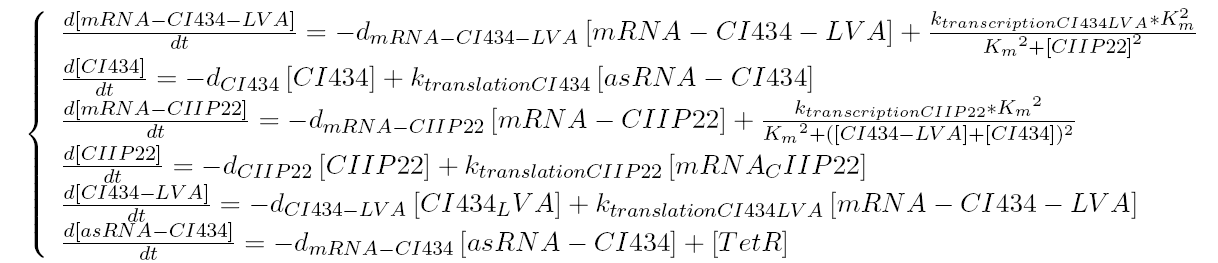

The existence of the two stable states of the memory (cI434_LVA high and cIIP22 low / cI434_LVA low and cIIP22 high) can be mathematically proven.

First we define the equilibrium points of the following differential equation system:

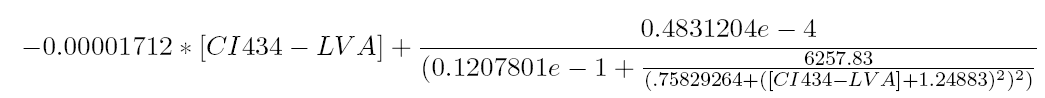

The equilibrium points are defined as the points for which all the derivatives are zero. Solving this non-linear system for [OmpF] equal to 0.00005 results in finding the roots of the equation

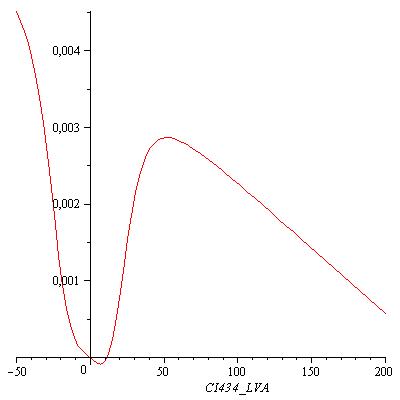

This equation has three real zeros ([CI434_LVA = 0.002435815407], [CI434_LVA = 11.52604711], [CI434_LVA = 233.6410112]) and two conjugated imaginary zeros ([CI434_LVA = -8.242012862+11.11131953*I], [CI434_LVA = -8.242012862-11.11131953*I]) as can be seen in the following figure:

The real roots of the system for all the variables are:

| Zero 1 | Zero 2 | Zero 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [CI434] | 1.248827120 | 1.248827120 | 1.248827120 |

| [CI434-LVA] | 0.002435815407 | 11.52604711 | 233.6410112 |

| [mRNACI434-LVA] | 0.00001804584283 | 0.08539121399 | 1.730939445 |

| [CIIP22] | 34.03962262 | 0.4824866257 | 0.001433763049 |

| [mRNACIIP22] | 1.765288021 | 0.02502165991 | 0.00007435466497 |

| [asRNACI434] | 0.02164042563 | 0.02164042563 | 0.02164042563 |

The stability of the three real zeros is defined by the eigenvalues of the Jacobian of the differential equation system. This Jacobian equals

The eigenvalues for Zero 1 are all negative (-0.2334056227e-2, -0.2286362516e-2, -0.3122380843e-3, -0.2645443732e-3, -0.9627000000e-4, -0.2310490600e-2). This is also the case for Zero 3 (-0.2319019326e-2, -0.2301889325e-2, -0.2795812737e-3, -0.2967112750e-3, -0.9627000000e-4, -0.2310490600e-2). These two zero's represent the two stable states of the memory system. Zero 2 has one positive eigenvalue (0.0002015903724) and is therefore unstable.

The following figure shows some trajectories in the phase plane ([CIIP22],[CI434-LVA]): there is a clear boundary between the two stable equilibrium points (the green dots) that goes through the unstable equilibrium point (the red dot). This boundary divides the two dimensional phase plane in two separate basins of attraction.

References

| [1] | A. E G H Wagner and R W Simons, “Antisense RNA Control in Bacteria, Phages, and Plasmids,” Nov. 2003; http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003433. |

| [2] | “ETHZ/Parameters - IGEM07”; https://2007.igem.org/ETHZ/Parameters. |

| [3] | J.A. Bernstein et al., “Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 99, Jul. 2002, pp. 9697–9702. |

| [4] | M. Bon, S.J. McGowan, and P.R. Cook, “Many expressed genes in bacteria and yeast are transcribed only once per cell cycle,” FASEB J., vol. 20, Aug. 2006, pp. 1721-1723. |

| [5] | J.B. Andersen et al., “New Unstable Variants of Green Fluorescent Protein for Studies of Transient Gene Expression in Bacteria,” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 64, Jun. 1998, pp. 2240–2246. |

| [6] | J. De Anda, A. Poteete, and R. Sauer, “P22 c2 repressor. Domain structure and function,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 258, Sep. 1983, pp. 10536-10542. |

| [7] | “Part:BBa B0031 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_B0031. |

| [8] | “Part:BBa B0033 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0033. |

| [9] | “Part:BBa R0040 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040. |

| [10] | “Part:BBa R0052 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0052. |

| [11] | “Part:BBa R0053 - partsregistry.org”; http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0053. |

| [12] | B.C. McCabe, D.R. Pawlowski, and G.B. Koudelka, “The Bacteriophage 434 Repressor Dimer Preferentially Undergoes Autoproteolysis by an Intramolecular Mechanism,” J. Bacteriol., vol. 187, Aug. 2005, pp. 5624-5630. |

"

"