Team:ESBS-Strasbourg/Modeling

From 2008.igem.org

(→Modeling) |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div id="header">{{Template:Team:ESBS-Strasbourg/Templates/Header}}</div> | <div id="header">{{Template:Team:ESBS-Strasbourg/Templates/Header}}</div> | ||

| - | <div id="maincontent" style="margin-top: | + | <div id="maincontent" style="margin-top:150px;"> |

| - | + | __notoc__ | |

| - | = | + | =Modeling= |

<br> | <br> | ||

From the very beginning of the development of our construct, modeling played a critical role to help us identifying necessary characteristics for a working system. We used Simulink that is very intuitive to handle (thanks to the Uni Karlsruhe for the support). The model never was sophisticated enough to reflect all aspects of a living system, but nevertheless should be sufficient to help finding rational solutions for basic problems. In the following, there is a short presentation of problems we solved thanks to information received from simulation assays. The tasks are presented in a chronological way, despite the fact that it was impossible to just concentrate on one problem isolated from other factors. The real process therefore was iterative for each question to deliver the best possible result in the context of the overall system. There are two main problems that are tightly linked to one another, but that shall be presented in a separate manner for the sake of clarity: | From the very beginning of the development of our construct, modeling played a critical role to help us identifying necessary characteristics for a working system. We used Simulink that is very intuitive to handle (thanks to the Uni Karlsruhe for the support). The model never was sophisticated enough to reflect all aspects of a living system, but nevertheless should be sufficient to help finding rational solutions for basic problems. In the following, there is a short presentation of problems we solved thanks to information received from simulation assays. The tasks are presented in a chronological way, despite the fact that it was impossible to just concentrate on one problem isolated from other factors. The real process therefore was iterative for each question to deliver the best possible result in the context of the overall system. There are two main problems that are tightly linked to one another, but that shall be presented in a separate manner for the sake of clarity: | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | =Problem N° 1: promoter construction | + | ==Problem N° 1: promoter construction== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | Given the basic design with self-activator (sA), repressor (R) and cross-activator (cA), there are always two transcription factor species regulating one promoter. The ratio of activator to repressor shall be critical for either activation or repression of the transcriptional activity of the module. It would be ideal to receive a switch-like behaviour with the system being either silent or showing maximal expression with a steep transition between the two states. This can be achieved by taking advantage of cooperativity in eucaryotic expression systems in general with the additional benefits of several operator repetitions. | + | Given the basic design with self-activator (sA), repressor (R) and cross-activator (cA), there are always two transcription factor species regulating one promoter. The ratio of activator to repressor shall be critical for either activation or repression of the transcriptional activity of the module. It would be ideal to receive a switch-like behaviour with the system being either silent or showing maximal expression with a steep transition between the two states. |

| + | This can be achieved by taking advantage of cooperativity in eucaryotic expression systems in general with the additional benefits of several operator repetitions. | ||

| + | This can be achieved by taking advantage of cooperativity effects that occur naturally in eucaryotic expression systems and that can be further enhanced by multiple operator repetitions. | ||

| - | Two different approaches came up by either using just one DNA-binding domain for activator and repressor acting on the same operator or using two distinct DNA-binding domains acting on | + | Two different approaches came up by either using just one DNA-binding domain for activator and repressor acting on the same operator or using two distinct DNA-binding domains acting on distinct operators. In the following we refer to these two approaches as One- and Two-operator system respectively. |

Characteristics with advantages and drawbacks: | Characteristics with advantages and drawbacks: | ||

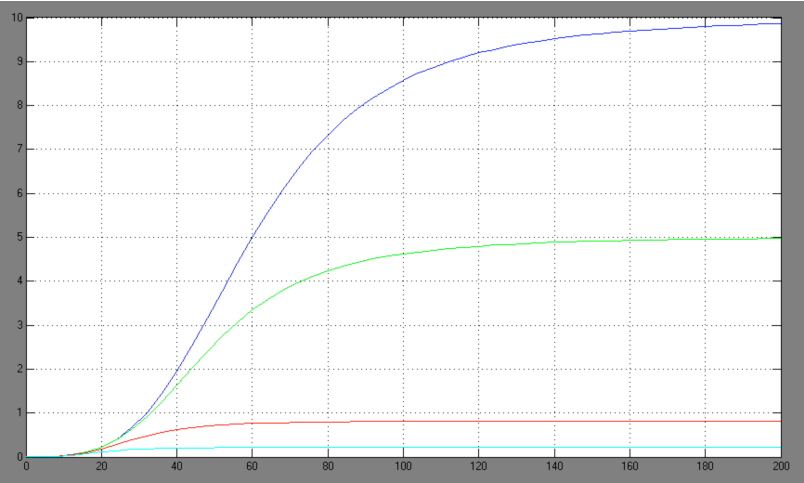

| - | [[Image:Comp_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px|Hill adapted competitive inhibition equation]] | + | [[Image:Comp_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px|Hill adapted competitive inhibition equation <br> blue: Act/Rep=1/0; green: Act/Rep=1/1; red: Act/Rep=1/2, cyan: Act/Rep=1/3]] |

One-operator system: | One-operator system: | ||

*activator and repressor bind to the same operator -> same DNA-binding domains; simplified promoter construction | *activator and repressor bind to the same operator -> same DNA-binding domains; simplified promoter construction | ||

*passive repression by competition for operator binding site | *passive repression by competition for operator binding site | ||

*active repression by repression domain | *active repression by repression domain | ||

| - | *problem of heterodimer formation as dimerisation domain is part of DNA-binding domain | + | *problem of heterodimer formation (an activator monomer bound to a repressor monomer) as dimerisation domain is part of DNA-binding domain |

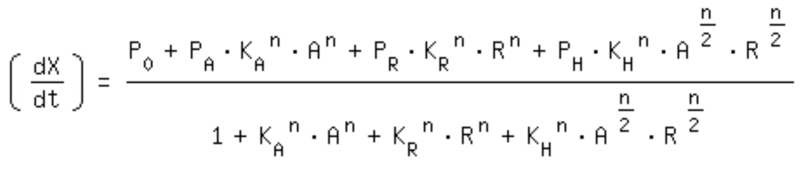

*-> competitive inhibition equation for passive repression effect, active repression effect and heterodimer influence primarily neglected: | *-> competitive inhibition equation for passive repression effect, active repression effect and heterodimer influence primarily neglected: | ||

[[Image:Comp_equa.jpg|250px]]<br> | [[Image:Comp_equa.jpg|250px]]<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

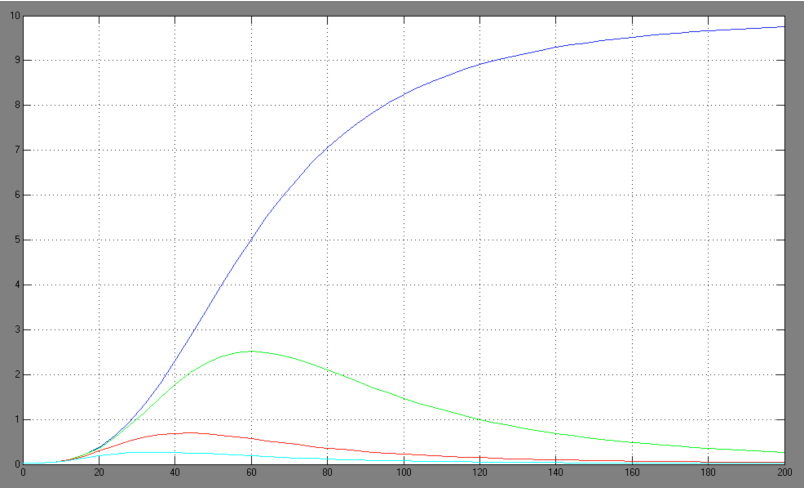

| - | [[Image:Comb_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px|Hill adapted combined activation/repression equation]] | + | [[Image:Comb_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px|Hill adapted combined activation/repression equation <br> blue: Act/Rep=1/0; green: Act/Rep=1/1; red: Act/Rep=1/2, cyan: Act/Rep=1/3]] |

Two-operator system: | Two-operator system: | ||

| - | * | + | *activator and repressor bind to distinct operators -> different DNA-binding domains |

*active repression by repression domain, but no passive effect | *active repression by repression domain, but no passive effect | ||

*system repressed at high repressor concentration independently of activator/repressor ratio | *system repressed at high repressor concentration independently of activator/repressor ratio | ||

| Line 36: | Line 38: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

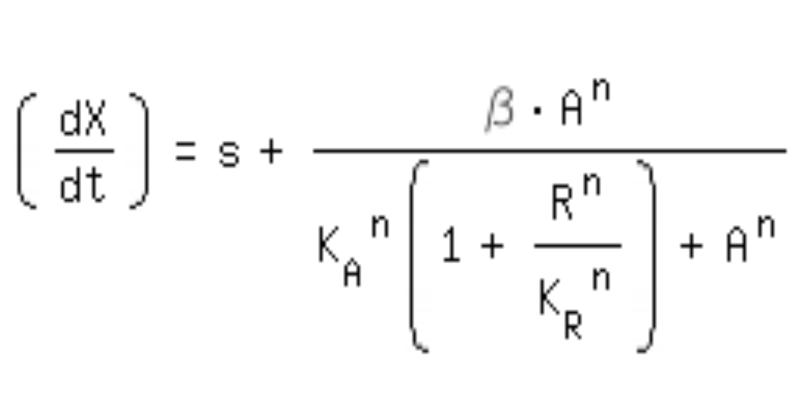

| - | [[Image:Spec_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px| | + | [[Image:Spec_graph.jpg|right|thumb|440px|Adaption from saturation equation of allosteric enzymes <br> blue: Act/Rep=1/0; green: Act/Rep=1/1; red: Act/Rep=1/2, cyan: Act/Rep=1/3]] |

| - | The One-operator system is the simpler construction and also delivers better results with a broader range of TF concentrations for a successfully switching system. Nevertheless, the equation for the | + | The One-operator system is the simpler construction and also delivers better results with a broader range of TF concentrations for a successfully switching system. Nevertheless, the equation for the One-operator system needs further adaptations concerning the active repression effect and the heterodimer influence to describe gene expression. It is unclear if the repressing effect of the repressor domain is stronger than the activating effect of the activator domain. There are few examples in literature where the two domains act in different concentrations on the same promoter. Furthermore, the impact of the heterodimers remains unclear as there might be preferences in homodimer formation. The position of the attached activator or repressor or homodimer in regard to the TATA-box might also play a critical role. Simplifying these problems, we considered an equation that is derived from the specific activation equation of allosteric enzymes as possible compromise: |

[[Image:Spec_equa.jpg|470px]]<br> | [[Image:Spec_equa.jpg|470px]]<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

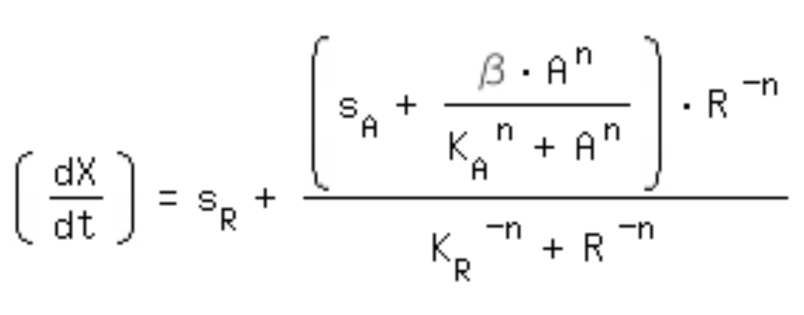

| - | =Problem N° 2: | + | ==Problem N° 2: activator/repressor impact== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | Expression of R and cA shall result in repression of the competing module | + | Expression of R and cA shall result in repression of the competing module. The graph of the equation of allosteric enzymes shows around 10% expression at higher activator to repressor concentrations of one to one. We therefor need to implement a mechanism that makes the repressing effect stronger than the effect of the cross-activator. This problem can be solved in several ways or through combinations of them: |

*reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA compared to R | *reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA compared to R | ||

*limiting the expression amount of cA compared to R | *limiting the expression amount of cA compared to R | ||

*taking advantage of the localisation effects with cell-cycle dependent NLS | *taking advantage of the localisation effects with cell-cycle dependent NLS | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | Depending on the choice of expression equation, the effect of reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA shows the same or similar result as a lower expression rate. The lower expression rate bears the advantage of a better standardisation between the two modules and also for further bits. Affinity mutations are different for each DNA-binding domain whereas differences in expression amount should always deliver the same concentration ratios. There are again two different ways to obtain different expression levels: one could either express the two genes from one single promoter | + | Depending on the choice of expression equation, the effect of reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA shows the same or similar result as a lower expression rate. The lower expression rate bears the advantage of a better standardisation between the two modules and also for further bits. Affinity mutations are different for each DNA-binding domain whereas differences in expression amount should always deliver the same concentration ratios. There are again two different ways to obtain different expression levels: one could either express the two genes from one single promoter seperated by an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) or from two different promoters comprising the same operator motif but different TATA box mutations. Taking advantage of cell-cycle dependent NLS would also be a very elegant method, but it is complicated to implement and also shows a narrow regulation window in several simulation assays. |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ==Switching systems== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

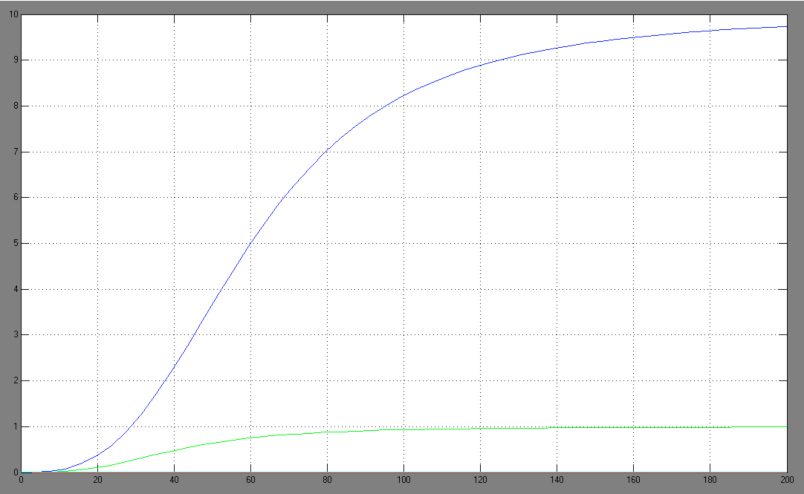

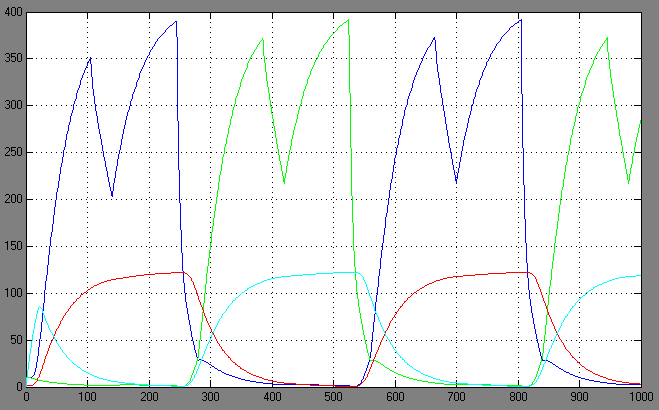

| + | [[Image:1.bit expr.PNG|left|thumb|450px|1st bit: expression pattern <br> blue: 0-module expression; green: 1-module expression]] | ||

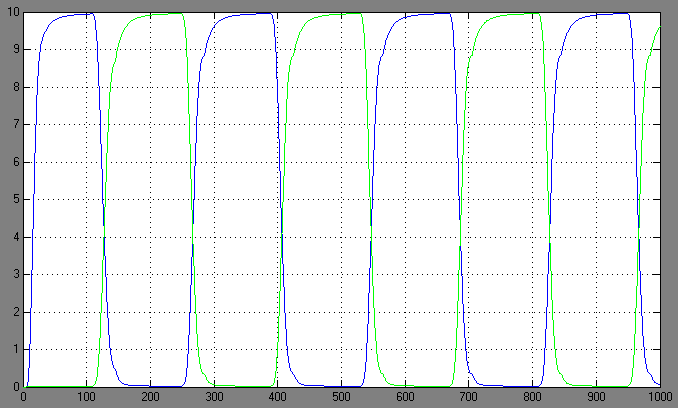

| + | [[Image:1.bit conc.PNG|right|thumb|450px|1st bit: transcription factor concentrations <br> blue: R0; green: R1; red: cA0; cyan: cA1]] | ||

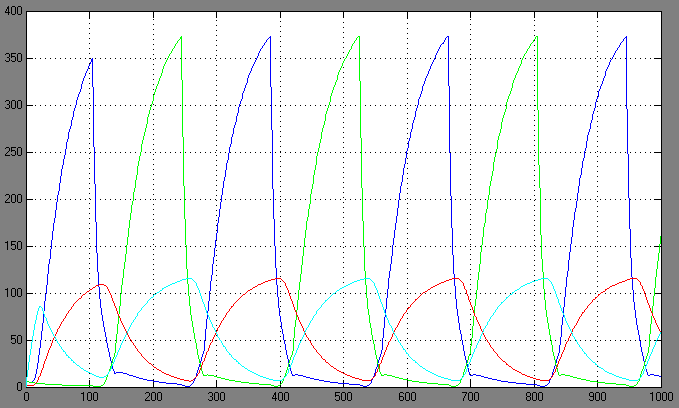

| + | [[Image:2.bit expr.PNG|left|thumb|450px|2nd bit: expression pattern <br> blue: 0-module expression; green: 1-module expression]] | ||

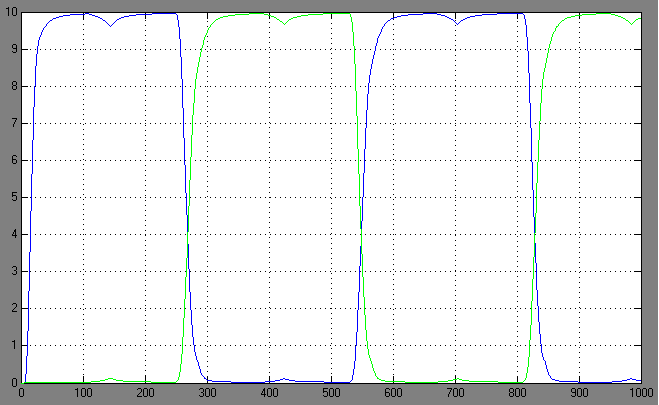

| + | [[Image:2.bit conc.PNG|right|thumb|450px|2nd bit: transcription factor concentrations <br> blue: R0; green: R1; red: cA0; cyan: cA1]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:12, 29 October 2008

Modeling

From the very beginning of the development of our construct, modeling played a critical role to help us identifying necessary characteristics for a working system. We used Simulink that is very intuitive to handle (thanks to the Uni Karlsruhe for the support). The model never was sophisticated enough to reflect all aspects of a living system, but nevertheless should be sufficient to help finding rational solutions for basic problems. In the following, there is a short presentation of problems we solved thanks to information received from simulation assays. The tasks are presented in a chronological way, despite the fact that it was impossible to just concentrate on one problem isolated from other factors. The real process therefore was iterative for each question to deliver the best possible result in the context of the overall system. There are two main problems that are tightly linked to one another, but that shall be presented in a separate manner for the sake of clarity:

Problem N° 1: promoter construction

Given the basic design with self-activator (sA), repressor (R) and cross-activator (cA), there are always two transcription factor species regulating one promoter. The ratio of activator to repressor shall be critical for either activation or repression of the transcriptional activity of the module. It would be ideal to receive a switch-like behaviour with the system being either silent or showing maximal expression with a steep transition between the two states.

This can be achieved by taking advantage of cooperativity in eucaryotic expression systems in general with the additional benefits of several operator repetitions.

This can be achieved by taking advantage of cooperativity effects that occur naturally in eucaryotic expression systems and that can be further enhanced by multiple operator repetitions.

Two different approaches came up by either using just one DNA-binding domain for activator and repressor acting on the same operator or using two distinct DNA-binding domains acting on distinct operators. In the following we refer to these two approaches as One- and Two-operator system respectively.

Characteristics with advantages and drawbacks:

One-operator system:

- activator and repressor bind to the same operator -> same DNA-binding domains; simplified promoter construction

- passive repression by competition for operator binding site

- active repression by repression domain

- problem of heterodimer formation (an activator monomer bound to a repressor monomer) as dimerisation domain is part of DNA-binding domain

- -> competitive inhibition equation for passive repression effect, active repression effect and heterodimer influence primarily neglected:

Two-operator system:

- activator and repressor bind to distinct operators -> different DNA-binding domains

- active repression by repression domain, but no passive effect

- system repressed at high repressor concentration independently of activator/repressor ratio

- only what is activated can also be repressed

- -> activation equation as maximal expression rate within the repression equation:

The One-operator system is the simpler construction and also delivers better results with a broader range of TF concentrations for a successfully switching system. Nevertheless, the equation for the One-operator system needs further adaptations concerning the active repression effect and the heterodimer influence to describe gene expression. It is unclear if the repressing effect of the repressor domain is stronger than the activating effect of the activator domain. There are few examples in literature where the two domains act in different concentrations on the same promoter. Furthermore, the impact of the heterodimers remains unclear as there might be preferences in homodimer formation. The position of the attached activator or repressor or homodimer in regard to the TATA-box might also play a critical role. Simplifying these problems, we considered an equation that is derived from the specific activation equation of allosteric enzymes as possible compromise:

Problem N° 2: activator/repressor impact

Expression of R and cA shall result in repression of the competing module. The graph of the equation of allosteric enzymes shows around 10% expression at higher activator to repressor concentrations of one to one. We therefor need to implement a mechanism that makes the repressing effect stronger than the effect of the cross-activator. This problem can be solved in several ways or through combinations of them:

- reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA compared to R

- limiting the expression amount of cA compared to R

- taking advantage of the localisation effects with cell-cycle dependent NLS

Depending on the choice of expression equation, the effect of reducing the affinity of the DNA-binding domain of cA shows the same or similar result as a lower expression rate. The lower expression rate bears the advantage of a better standardisation between the two modules and also for further bits. Affinity mutations are different for each DNA-binding domain whereas differences in expression amount should always deliver the same concentration ratios. There are again two different ways to obtain different expression levels: one could either express the two genes from one single promoter seperated by an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) or from two different promoters comprising the same operator motif but different TATA box mutations. Taking advantage of cell-cycle dependent NLS would also be a very elegant method, but it is complicated to implement and also shows a narrow regulation window in several simulation assays.

Switching systems

"

"