Team:UC Berkeley/GatewayPlasmid

From 2008.igem.org

(→Gateway Device in Assembly Vector: Plasmid Details) |

(→Gateway Device in Assembly Vector: Plasmid Details) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

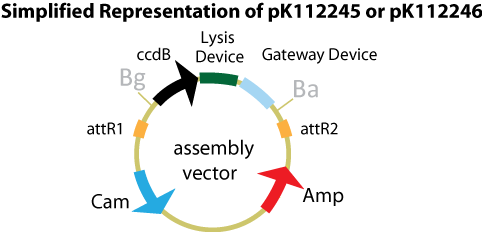

| - | '''Entry Vector:'''The entry vector used in both cases was pBca1256 | + | '''Entry Vector:'''The entry vector used in both cases was [https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2008/8/85/PBca_1256.png pBca1256].<br> |

| - | + | <br> | |

[[Image:simpof1256.png]] <br> | [[Image:simpof1256.png]] <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 03:06, 30 October 2008

Introduction

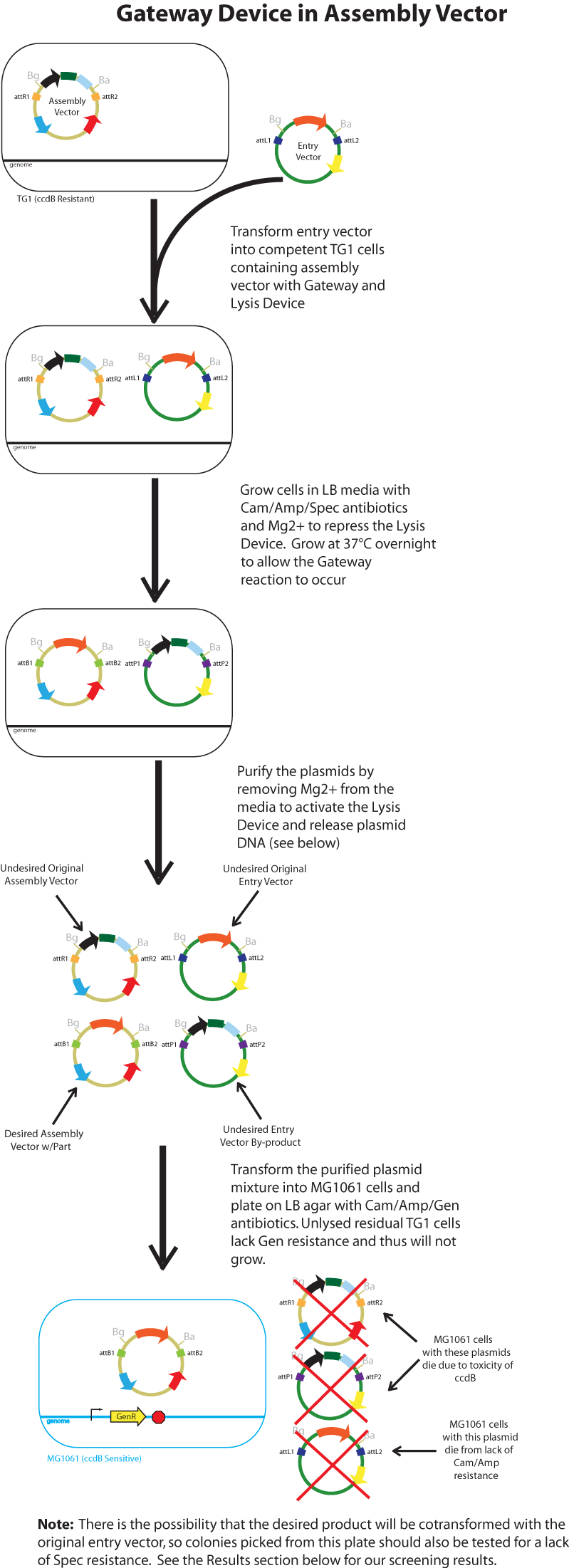

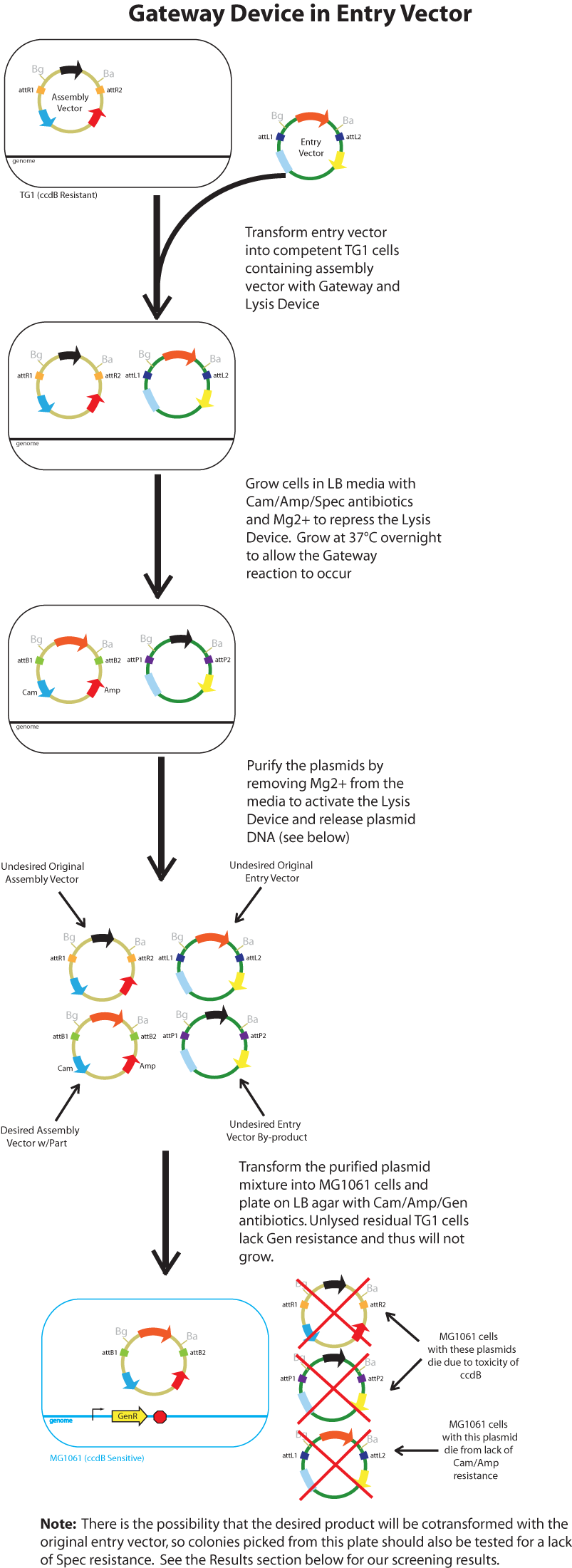

The current in vitro LR Gateway procedure for transferring one piece of DNA into another vector without restriction enzymes involves an expensive cocktail of purified plasmids, excisionase, integrase, ihfα and ihfβ. Both an assembly vector (containing the ccdB gene flanked by attR1 and attR2 sites for negative selection) and an entry vector (containing the part(s) desired to be transferred, flanked by attL1 and attL2 sites) are used as the substrates to which the reactants are added.

Inspired by such innovation, we seek to perform this task in vivo using E. coli to express the reactants necessary. Since E. coli naturally express ihfα/β in their genome, we first tried to integrate excisionase and integrase genes into the genomic DNA as well. However, this proved to be toxic to the cells, making them relatively unstable. Therefore, our next approach was to introduce the reagents into the substrate plasmids. In one case, the the assembly vectors received the Gateway device of the enzymes excisionase and integrase preceded by a temperature sensitive promoter, while in the other case it was introduced into the entry vectors. In both cases, we also explored the effects of additionally introducing the ihfα and ihfβ genes behind the Gateway device.

After careful analysis of our data, we introduced our Lysis device in order to eliminate the mini-prepping procedures and to thus make the entire process cheaper and more efficient.

Gateway Device in Assembly Vector: Plasmid Details

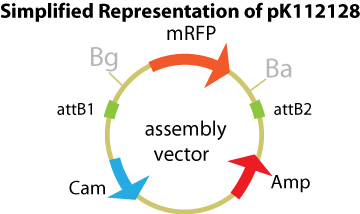

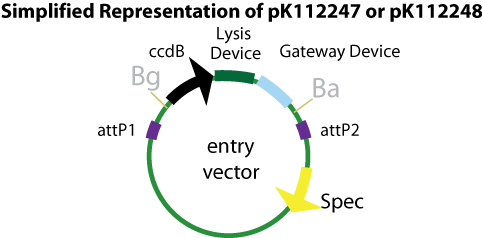

Assembly Vectors:Two different variations of the pK112128 assembly vector were created: one with {promoter.xis.int!} and one with {promoter.xis.int!}{rbs.ihfα!}{rbs.ihfβ!} between the ccdB site and the attR2 site. These plasmids are named pK112245 and pK112246 respectively. A simplified version of the two variants along with the Lysis Device is shown below.

Entry Vector:The entry vector used in both cases was pBca1256.

Gateway Device in Entry Vector: Plasmid Details

Assembly Vector:The assembly vector used for each of the following entry vector variations is pK112128.

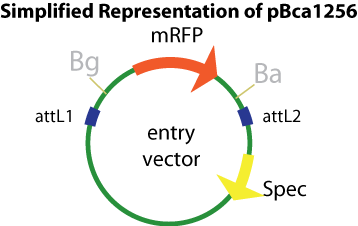

Entry Vectors: Two different variations of the pBca1256 entry vector were created: one with {promoter.xis.int!} and one with {promoter.xis.int!}{rbs.ihfα!}{rbs.ihfβ!} just before the attL1 site. These plasmids are named pK112247 and pK112248 respectively (see links below).

General Procedure

Below is a flowchart of the general plasmid based Gateway procedure. Due to various combinations of assembly and entry vectors explored, the "Gateway Device" was created to represent the {promoter.xis.int!} sequence with or without the adjoining {rbs.ihfα!}{rbs.ihfβ!} sequence. The "Lysis Device" sequence (which was only tested in the pK112245 assembly vector) was similarly simplified.

The major combinations of assembly + entry vectors are: pK112245 + pBca1256, pK112246 + pBca1256, pK112128 + pK112247, and pK112128 + pK112248. Additionally, pBca1256 with five different sized parts replacing the original mRFP part was also tested with each assembly vector to show the Gateway reaction can be done with parts of all sizes, although this is not shown in the diagram below.

Results

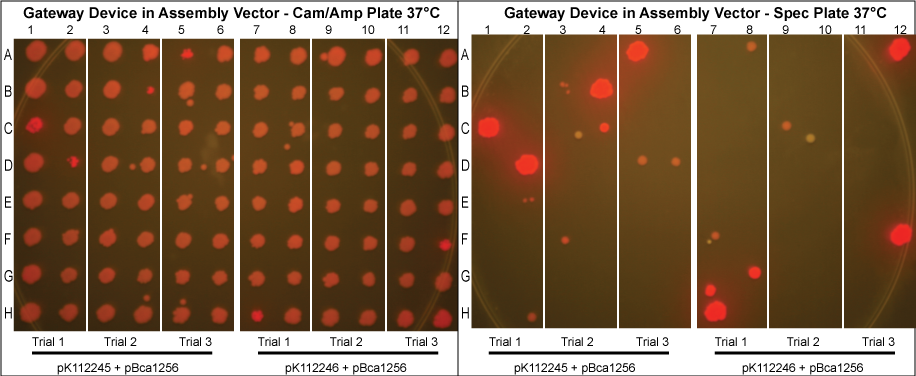

Gateway Device in Assembly Vector

- Control done at 30°C.

- As can be seen above, there is a relatively high rate of cotransformation as seen by the growth of colonies on the Spec plates. The trials done at 30°C had a higher rate of cotransformation likely because there were fewer plasmids resulting from the Gateway reaction.

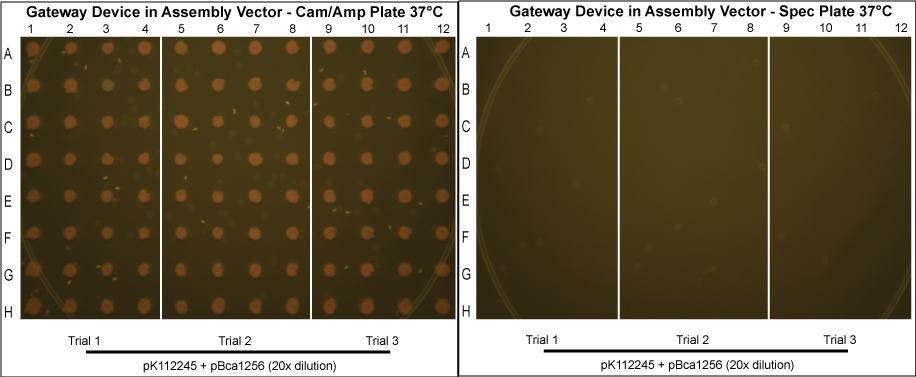

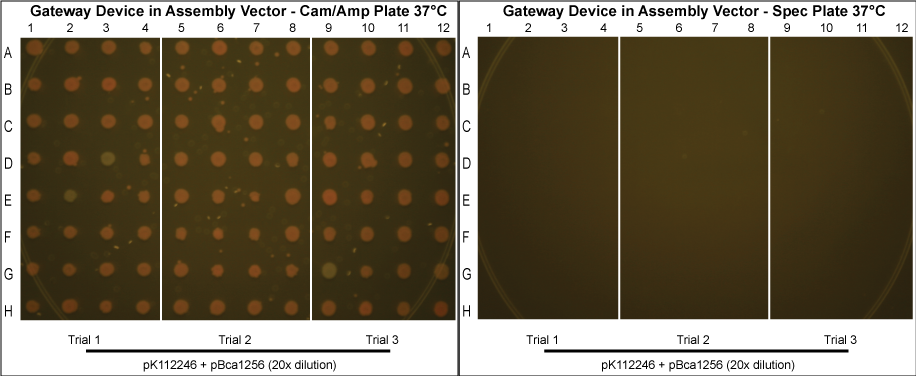

- In an attempt to reduce cotransformation rates in those grown normally at 37°C, we repeated these experiments, picking more colonies and diluting the purified protein mixture 20x before transformation into MG1061 cells. The results are shown below.

- Although these plates have not been allowed to grow as long and thus are not as bright in color, it can clearly be seen that cotransformation has been successfully eliminated.

The Lysis Device

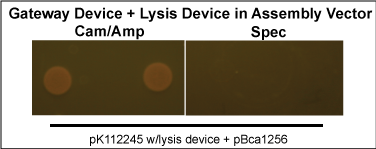

- The lysis device was inserted into the pK112245, and the experiment repeated. However, only 2 colonies grew, although both were free of cotransformation.

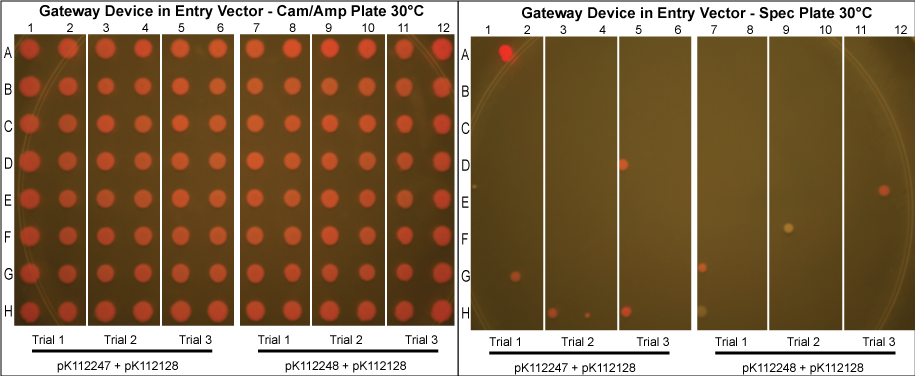

Gateway Device in Entry Vector

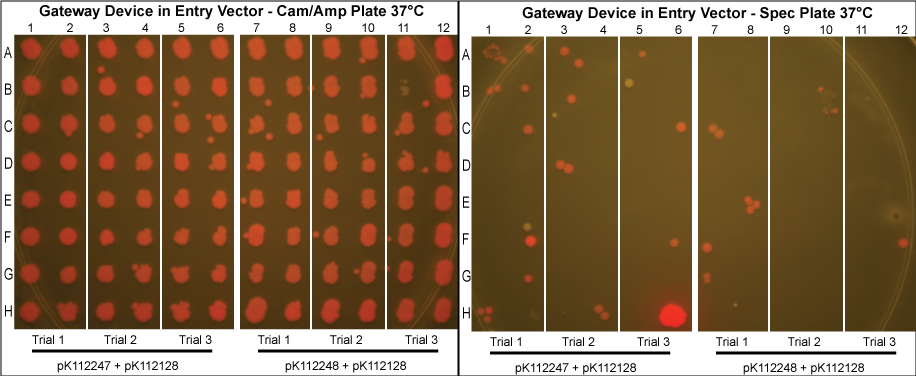

- As can been seen above, the Gateway reaction worked with much more efficiency as evidenced by the low rates of cotransformation.

Materials & Methods

We first prepared competent TG1 cells (resistant to ccdB) with the given assembly vector. The assembly vector was transformed into competent TG1 cells and were grown in liquid LB media with Cam/Amp antibiotics (and 50mM Mg+2 if the lysis device is included) at 30°C overnight. The following day, 20 ul of the saturated culture was taken out, and was grown under the same conditions to mid-log. About 1 ml of culture was pelleted, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in 10 ul KCM plus 90 ul TSS on ice.

Using these new competent cells, the given entry vector was tranformed into them. They were grown in liquid LB media with Cam/Amp/Spec antibiotics (and 50mM Mg+2 if the lysis device is included) at 37°C overnight to ensure the cells contain both plasmids and that the temperature sensitive promoter of the gateway device would turn on. A control in which the cells were instead kept at 30°C was conducted to compare our results with those in which the gateway device was theoretically off.

The following day, the plasmid from about 2 ml of saturated culture was purified. When there was no lysis device in the assembly vector, plasmid purification was achieved with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit. In the case where the lysis device is integrated into the assembly plasmid, the culture was pelleted, the supernatant removed, resuspended in 1 ml PBS, pelleted, the supernatant removed, and finally resuspended again in 100 ul PBS.

The purified plasmids were next transformed into MG1061 cells (sensitive to ccdB). These were plated on LB agar plates with Cam/Amp antibiotics and grown overnight at 37°C. The next day, 16 colonies were picked from each plate, spotted on a Cam/Amp antibiotic plate, as well as Spec antibiotic plate to test for cotransformance of the entry vector with the desired product.

The above procedure were conducted in parallel with different combinations of assembly and entry vectors. The following combinations of assembly and entry vectors were done: pK112245 + pBca1256, pK112246 + pBca1256, pK112128 + pK112247, and pK112128 + pK112248. Each combination included a control in which the Gateway device was not turned on during the allotted time for the reaction to occur (i.e. they were grown at 30°C, when the temperature sensitive promoter is off). In addition to this, three trials of each were conducted. Finally, in order to see if gateway could be performed on parts of different sizes, five different parts in pBca1256 were chosen (Bca1117, Bca1133, Bca1270, Bca1252, and Bca1168) and tested with the assembly vector pK112245, as well as with pK112245. One colony from each was sequenced to ensure gateway had occurred by identification of attB1 and attB2 sites as well as the parts in the assembly vectors.

After data analysis, we suspected that higher efficiency could be achieved for the schemes in which the Gateway Device was in the assembly vector if less plasmid was used to transform into MG1061 cells. Therefore, we took the post-reaction purified plasmid mixtures from the trials involving pK112245 + pBca1256 and pK112246 + pBca1256 and diluted each 20 times. Three trials for each in which the 20x dilution of the purified plasmid was transformed into MG1061 cells was performed under the same conditions, and 32 colonies from each plate were picked the following day.

Other controls were also performed. Each assembly vector used was also transformed into into MG1061 cells which were put on Cam/Amp antibiotic LB agar plates to make sure ccdB was sufficient for negative selection. Only a very few number of white colonies grew for each, which was expected since it is known that ccdB is prone to mutation and weakening. The entry vectors were also each individually transformed into MC1061 cells and plated on Cam/Amp antibiotic plates. No colonies appeared, proving that the entry vector did not contain Cam/Amp resistance.

Discussion

- Our desired product is a reacted assembly vector with the entry vector mRFP (or part) between attB1 and attB2 sites. Since the origin of replication in the assembly vectors is low-copy, the cells should appear light pink in color.

- Colonies that are bright pink, which grow on both Cam/Amp and Spec antibiotic plates, are cotransformed. This means that in addition to our desired assembly vector-with-part plasmid, one of the original, unreacted entry vectors has entered into the cell. These appear as bright pink because the origin of replication in the entry vector is high-copy.

- White colonies first appeared to be evidence of a mutation in the ccdB gene such that it inhibits its toxicity. Since ccdB is used to negatively select against the original, unreacted assembly vector containing ccdB flanked by attR1 and attR2, a mutation which weakens ccdB such that a strain sensitive to normal ccdB can grow in spite of the gene's presence and gives undesirable background products. However, after sequencing 4 different white colonies, we discovered that in each case the mRFP gene was indeed inserted into the assembly vector and was flanked by attB1 and attB2 sites (our desired product); the only problem was that there were deletions (24 or 25 bp in length) in the promoter of the part which was driving the expression of mRFP! Thus, the few white colonies seen are likely due to mutations in the original part rather than a mutation in ccdB.

- There are also some colonies that are very slightly pink. We predict that these are cells which contain the desired assembly vector-with-part plasmid, but that the part itself has sustained some sort of mutation (perhaps again in the promoter) that slightly weakens the expression of mRFP.

- Proportionally, the less background we receive at the end of the experiment, the more efficient the plasmid based Gateway reaction is.

- From our experimental results comparing the "Gateway Device" with and without ihfα/β, we conclude that the additional expression of ihfα/β is unnecessary and makes no difference in the plasmid based gateway reactions. However, based on the difficulty of previous attempts to join and clone ihfα and ihfβ, it has been concluded that these parts are unnecessary or even hazardous to cells, and thus will not be explored further in other Gateway schemes.

- Our data suggests that our procedure was most efficient when the Gateway Device was located in the entry vectors as opposed to the assembly vectors. This makes sense since the entry vector origin of replication is high copy, meaning the reagents necessary for the reaction to occur (excisionase, integrase, ihfα and ihfβ) will be expressed at much higher levels when the temperature sensitive promoter is turned on. More reagents produced increases the probability that the Gateway reaction will occur within a given cell, and that we will get our desired product with the greatest efficiency. However, from experience in creating and cloning the Gateway Device, we know that this composite part is somewhat toxic to the cell since there are att sites in the genomic DNA of E. coli. Thus, it is necessary to carefully control this device with, in this case, a temperature sensitive promoter. This also means that if the "part" in your entry vector is also somewhat toxic, the additional toxicity of the Gateway Device may make the entry vector difficult or even impossible to make in the first place.

- Therefore, it is most beneficial to put the Gateway Device into the assembly vector. In order to improve the efficiency and reduce the background in these cases, we diluted the post-reaction purified plasmid mixtures from the trials involving pK112245 + pBca1256 and pK112246 + pBca1256. Our results show a significant reduction in cotransformation and thus a higher rate of efficiency.

- The entry vectors with the various part lengths replacing mRFP in pBca1256 all sequenced correctly; the attB1 and attB2 sites were confirmed for all experiments. This suggests that the plasmid based gateway reaction with pK112245 and pK112246 assembly vectors works for parts as short as 250bp and as long as 3078bp.

- All in all, we were able to successfully conduct the Gateway reaction in vivo using assembly and entry plasmids with relatively high efficiency. Our problems with cotransformation seem to largely reduced upon diluting the purified plasmid before transformation. The white colony background due to mutated, weakened ccdB may be solved by replacing it with or adding on another more robust toxic protein, such as barnase, to aid in negative selection. Another possibility would be to use positive selection, for example by using conditional replication of an origin.

- Although the plasmid based Gateway scheme has proven to be successful, we have also tried other methods to achieve the Gateway reaction: see Phagemid Based Gateway and Genomic Based Gateway.

"

"