Team:TUDelft/Temperature design

From 2008.igem.org

Bavandenberg (Talk | contribs) |

Bavandenberg (Talk | contribs) (→Phase II: Changing the temperature threshold of the RNA thermometer) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

Revision as of 09:59, 1 September 2008

>> work in progress

Contents |

Parts Design

Phase I: Introducing an RNA thermometer into e. Coli

The first phase will be used to test if known RNA thermometers can be turned into standard biobricks and incorporated, iGEM style, into e. coli. A literature study is done to find RNA thermometers that are tested and proven to be working RNA thermometers.

We selected three RNA thermometers (one per RNA thermometer family) that were retrieved from different organisms(3ref). A fourth working RNA thermometer attracted our attention because it was not an RNA thermometer retrieved from an organism, but a designed one(ref). Unfortunately, as would come true later, this RNA thermometer cannot be turned into a biobrick.

The three selected RNA thermometers

The first RNA thermometer is one of the ROSE family and is retrieved from the organism Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Repressor Of heat-Shock gene Expression (ROSE) is the (conserved) mRNA sequence found in front of some prokaryotic heat-shock proteins [1]. Turning this into a biobrick should give an RNA thermometer that is switched off at 30 °C and allow induction of translation by heating to 42 °C.

The second RNA thermometer is one of the FourU family and is retrieved from Salmonella. Various pathogenic microorganisms express virulence proteins only inside a host. It has been shown in the 90's this is induced by the increased temperature having effect on translation but not on transcription [2]. Examples of microorganisms using this temperature induced virulence are Salmonella [3] , Yersinia pestis or Listeria monocytogenes. Of course we won't work with these virulent genes, only with the regulating mRNA sequences in front of them or their TF. An induction temperature of 37 °C seems logical.

The third RNA thermometer is retrieved from the Listeria monocytogenes and belongs to the PrfA family. The switching temperature is at 37 degrees Celsius.

Properties of the 3 used DNA pieces...

Artificial RNA thermometer based on G-quadruplex

A fourth working RNA thermometer found in literature is an artificial one. It is based on a special tertiary (3D) structure in which an RNA stretch can fold. This structure also occludes the Shine Dalgarno region and thereby blocks the translation. Above a certain threshold temperature the structure becomes unstable and the Shine-Dalgarno becomes exposed, enabling the ribosome to bind to the RNA and initiate the translation process. Although this artificial RNA thermometer is very interesting, it turned out to be impossible make a biobrick out of it. As can be read in the design part (link) the scar (the result of the ligation of the RNA thermometer part with the protein coding part) has to be introduced in the RNA thermometer. Unfortunately the introduction of the scar changes the structure that makes the part temperature sensitive. Therefor this G-quadruplex RNA thermometer is not taken into account any further. Still it remains very interesting, because it shows that an artificial thermometer can be made using only the structure of the RNA.

Scar problem

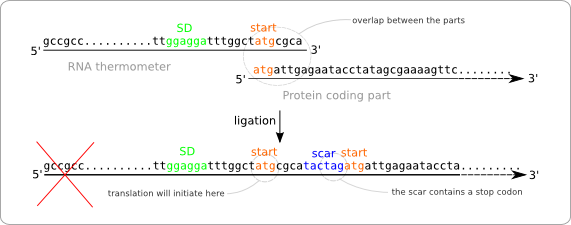

Turning the RNA thermometer sequences into standard biobricks is not as straightforward as adding a prefix and suffix to the found sequences. The reason for this is that the start codon of the protein coding part following the RNA thermometer is also part of the RNA thermometer sequence (figure ... sequences met atg overlap). The problem with this approach is that the ligation of the two parts results in a sequence containing two start codons with in between the scar (figure ... wrong situation sticking together two parts). The first of these start codon (the one on the RNA thermometer) will act as the initiation point for the translation, because of its distance to the Shine Dalgarno sequence. At first some extra amino acids will be added to the protein, but even worse, the protein will not be translated at all. This is because of the scar that contains a stop codon. So the translation will already end before the protein coding region is reached.

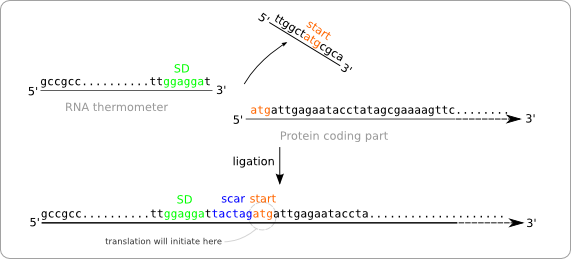

To solve this problem we have to alter the sequence of the RNA thermometer. Alteration of the protein coding part is of course no option because we are aiming for a standard part that can be combined with any other standardized protein coding part. So these parts, that always start with a start codon should be kept intact. The simple solution is to chop of the last part of the RNA thermometer sequence, which will be replaced by the scar and the start of the protein coding part after ligation (figure ... solution without scar adaption).

But this results in a new problem. The alteration of the RNA thermometer sequence also changes its secondary structure and that will also affect its function as temperature sensor (figure ... change of secondary structure). To resolve this we made some extra alteration in the RNA thermometer sequence at the opposite position of the scar in order to regain the original secondary structure.

We applied this procedure to three of the four RNA thermometers that we got from the literature. We used the Vienna RNAfold webserver to predict the secondary structure of the original RNA thermometer and the altered sequence. We regained the original secondary structure using a trial and error approach adding different nucleotides opposite of the added scar...

The fourth RNA thermometer, the artificial one based on the G-quadruplex structure, will loose its temperature sensitivity when the scar is introduced into the sequence. It happens to replace multiple G nucleotides that make up the G-quadruplex structure which is responsible for the temperature sensitivity.

Having designed sequences that have the same secondary structure does not guarantee the same functionality. The pairing nucleotides around the Shine Dalgarno region are changed, so the temperature needed to expose the Shine Dalgarno sequence will probably be changed. Tests will have to point out what the switching temperature of the RNA thermometer parts will be. This is of course if the parts work at all. There are probably a lot of factors (more than the predicted secondary structure can tell us) that play a role in the temperature sensing process, also many that we don't now of. Even one mutation can already lead ...

References

- ^ Chowdhurry S, Maris C, Allain F H T, Narberhaus F (2006). "Molecular basis for temperature sensing by an RNA thermometer". The EMBO Journal, 2006, 25, 2487–2497. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16710302 PMID:16710302]

- ^ Hoe N P, Goguen J D (1993). "Temperature sensing in Yersinia pestis: Translation of the LcrF activator protein is thermally regulated". J Bacteriol, 1993 December, 175(24), 7901-7909. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7504666 PMID:7504666]

- ^ Waldminghaus T, Heidrich N, Branti S, Narberhaus F (2007). "FourU: a novel type of RNA thermometer in Salmonella". Molecular Microbiology, Volume 65, Issue 2, 413-424. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17630972 PMID:17630972]

- ^ Wieland M, Hartig J (2007). "RNA Quadruplex-Based Modulation of Gene Expression". Chemistry & Biology, Volume 14, Issue 7, 757-763. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17656312 PMID:17656312]

"

"