Team:TUDelft/Research Proposal

From 2008.igem.org

Contents |

Research Proposal

Background

The international Genetically Engineered Machines or iGEM competition is an initiative of the Massachusetts Institute for Technology (MIT). From 2005 on this competition in synthetic biology has been organized and grown from five participants in 2005 to 80 participants this year. Basically the iGEM competition likes to address the following question: "Can simple biological systems be built from standard, interchangeable parts and operated in living cells? Or is biology just too complicated to be engineered in this way?" The three main reasons to begin organizing iGEM were [1]:

1. To enable the systematic engineering of biology

2. To promote the open and transparent development of tools for engineering biology

3. To help construct a society that can productively apply biological technology

In practice, the first two reasons comprise constructing an open source library of standardized biological parts. These parts of standardized stretches of DNA are called BioBricks. These BioBricks can be used to make sensory systems, oscillators, or other applications that can be performed by bacteria. The standardization of the parts is achieved by placing a known standard sequence before and after each part (pre- and suffix) that is made. The prefix and suffix consist of three known restriction enzyme sites, this means every part can be cut and pasted if the right combination of restriction enzymes is used. Of course this requires the restriction sites to be absent in any of the stretches of DNA between pre- and suffix. At present, there are thousands of these BioBricks. These make up promoters, terminators, regulatory elements and protein coding sequences of different sorts are some examples of what the BioBricks are. Within this setting student teams from all over the world are challenged to build an applicable system and add parts to the BioBrick library. Participants are encouraged to pursue ambitious projects, although there are no real requirements other than that it has fit into the iGEM setting.

Our aim is to make Escherichia coli act as a thermometer, showing different colors when incubated at different temperatures. A micro sized thermometer can serve a number of purposes, e.g. creating surface temperature profiles in electronic and biological devices [2]. Also these thermometers can play a analytical role in industrial fermentation. Controlling the temperature within a large volume is a big issue in industrial fermentations. If the temperature should not come above (or below) a certain threshold temperature, one could add the thermometer bacteria to the fermentation. With these bacteria added, it is possible to see whether the temperature did exceed the threshold by looking at the color of the bacteria. Another application would be to deliver on demand temperature inducable gene expression. The designed RNA sequences could be used to produce any gene above a chosen threshold temperature. The advantage of this system is that it does not need a chemical for induction that potentially can interfere with cellular processes. Within the iGEM open source setting, these sequences would become available to everyone.

Goals

Our project comprises several research goals. The first goal is to construct an RNA thermometer [3] in vivo. Because it is probably not feasible to construct the whole system in the time available we will focus on several subgoals that would help create the RNA thermometer in future. These subgoals are: providing a sound theoretical basis for the functioning of an in vivo RNA thermometer, designing and testing temperature sensitive stretches of RNA and cloning protein coding sequences of enzymes involved in the color pathway. We will focus on standardizing all parts made during the project according to iGEM regulations. The second goal is to predict behavior of this system using computer models. The third goal of this project is to focus on ethical considerations of synthetic biology in general (on a macro scale) and the implications of using synthetic biology within the open source technology setting of iGEM (on a micro level).

For sensing temperature (input) we are focusing on RNA thermometers. From literature, we will take 5’ UTR RNA sequences from organisms that have temperature sensitive induced protein expression or synthetic RNA sequences that have been shown to be able to induce temperature sensitive translation. The sources of these 5’ UTR sequences are heat shock proteins from e.g. Bradirhizobium japonicum [4], transcription factors from pathogenic bacteria [5][6] and designed temperature sensitive sequences [8]. We will screen different varieties on the designed RNA thermometer sequences. Furthermore, we want to make an inducible system, so all influences except temperature can be kept constant. How an RNA thermometer works in vivo is depicted in figure 1.

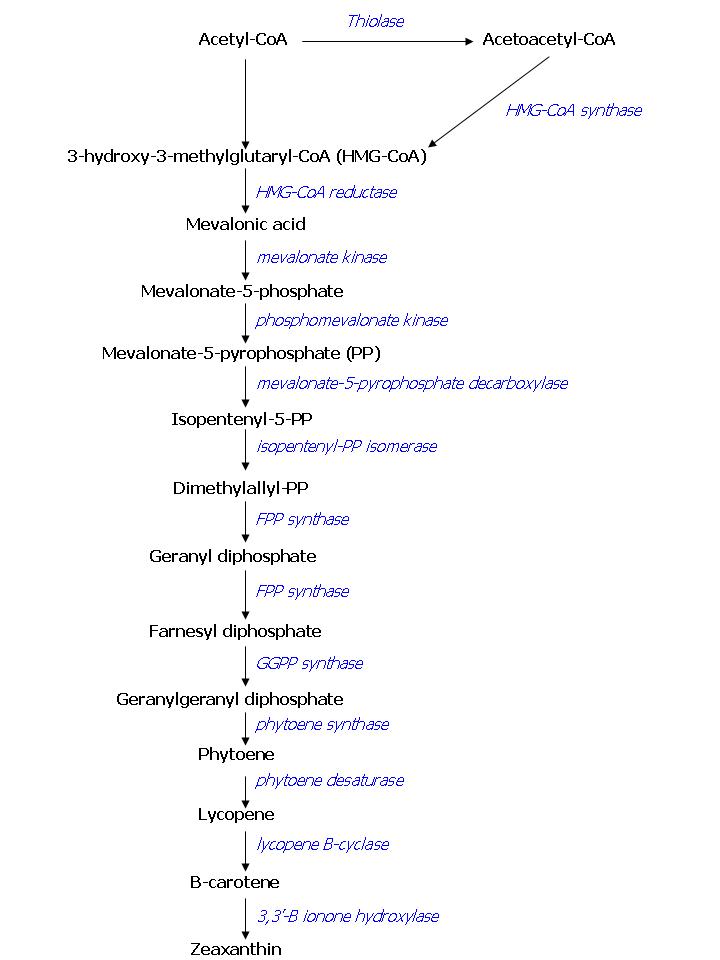

For the output on the system we want to obtain visibly colored E. coli colonies. To achieve this, we will introduce enzymes that originate from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and overexpress other E. coli enzymes in E. coli. These enzymes have been shown to be able to produce Farnesyl Pyrophosphate (FPP) in E. coli [7]. FPP is a precursor for pathways that lead to color production. When production of FPP in E. coli is achieved, the production of color will be the next goal. To obtain colored cells we could use the standardized pathway that is already made available by another iGEM-team (Edinburgh 2007).

Labwork

During this project we will work with E. coli K12 derived strains. For both the thermometer and the FPP pathway, E. coli will be transformed. In order to do this, vectors containing the relevant (c)DNA of the genes or temperature sensitive RNAs will be cloned into vectors provided by iGEM. Protocols available on the OpenWetWare (OWW) website will be followed in the laboratory. If no protocols are available on the OWW website, supplier’s protocol will be followed or we will make our own protocols.

An inducible system will be made in order to keep environmental conditions as equal as possible in all tests. All cells will be grown at 37oC, induced, and placed at different temperatures to investigate the temperature sensitive RNA structures. The lac operon will be in place before the RNA structures and after that the luciferase protein.

The lac operon can be induced by the presence of Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), a molecular mimic of allolactose, a metabolite of lactose. By spraying IPTG on dishes, a concentration between 100 µM and 1.5 mM of IPTG should be reached in order to induce the system effectively.

The inducible temperature sensitive RNA structures will be tested by luciferase assays. Luciferase will be expressed under control of a standard promoter and temperature sensitive RNA. Luciferase is a 62 kDa protein obtained from the firefly. Luciferase catalyzes (in the presence of Mg2+) the bioluminescent reaction (1):

luceferin + ATP + O2 --> oxyluceferin + AMP + PPi + CO2 + light (1)

The amount of light produced by this reaction can be measured and gives as a clue about the relative amount of luciferase present. The amount of luciferase present correlates with promoter strength and the effect of the temperature sensitive RNA present. As long as cells from the same bacterial colony (i.e. cells with the same amount of plasmids present and the same RNA temperature sensitive part and promoter) are handled, relative expression of luciferase induced at different temperatures can be compared. For creating variations in the riboswitch structures, we intend to introduce small (One or two mutations in the sequence) alterations in the DNA. We can achieve this, for example, by performing error-prone Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Screening of the resulting RNA sequence library could again be performed by LacZ screening at different induction temperatures. This way, we might be able to create RNA thermometers sensitive to different temperatures.

As has been stated before, FPP overproduction is needed to produce colored E.coli. In E. coli there is endogenous expression of FPP, it is produced by the DXP pathway. Simply overexpressing this pathway has led to only small increases in FPP production, as there are enzymes involved with very limited capacity. This is why we seek to overproduce FPP in another way. The color pathway we want to introduce consists of endogenous E. coli enzymes combined with enzymes ‘borrowed’ from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, some of the mevalonate pathway. It has been shown that this combination of enzymes is a more potent producer of FPP than the endogenous DXP pathway [7]. An overview of the compounds involved in the color pathway with names of the enzymes can be found in figure 1. To investigate the presence of the enzymes of the FPP pathway in transformed E. coli, we will screen for the products of the pathway in the transformed cells and compare them to wild type E. coli. This screening will be performed using gas chromatography or mass spectrometry analysis. Overexpressing FPP in E. coli bears a potential risk to the cells while FPP is toxic to E. coli if present in high concentration [7]. One way to prevent a concentration buildup of FPP within the cell is by draining the FPP pool by expressing a colorant, as we plan to do. However, it will be important to tune FPP production: there should be enough to produce a visible color, but not more than the enzymes that produce the color can handle.

Modeling

Part of the project will be focused on building models to predict the dynamic behavior of mRNA and proteins in the cell taking into account the effects of temperature on translation. The software used to model the metabolic activities in the cell is CellDesignerTM and/or MATLAB. The goal of setting up a mathematical model of the biological processes is to avoid pitfalls that can be predicted beforehand.

Furthermore, the modeling of the system is in itself a goal: results from the laboratory can be used to test the model. Using the results, the model could be changed or optimized by fitting the parameters using experimental data. We aim to be able to predict at what temperature these RNA thermometers will allow translation using mathematical models.

Besides these models we will investigate in silico how to alter the temperature sensitivity of the 5' UTR by mutating the RNA sequence. Alteration of this sequence will change the stability of the RNA secondary structure occluding the ribosome binding site (RBS). More stable structures will denaturate at higher temperatures while less stable structures will denaturate at lower temperatures. This way we aim to design temperature sensitive sequences that act at different temperatures. We will use mfold [9] and the Vienna RNA package [10] to predict the secondary structures and their stability.

Ethical considerations on macro and micro level

Synthetic biology can generally comprise several goals. Some would say the goal is to make biology an engineering science, designing with biology. Others may state that building with biology can be used to further understand life. At the least, one may state that both the bottom-up, constructing part and the top-down, deconstructing aspects of synthetic biology rely on the principle of using more or less biological systems in a more or less natural way. This new approach of biology brings about new applications, but also new risks and new ethical considerations. The question is to what extent the participants in the iGEM competition realize this. We are interested in what these new ethical considerations as proposed by ethicists in the field of synthetic biology actually mean for the participants in iGEM. On an individual level, which ethical questions play a role for the TU Delft iGEM team? How do the team members work with or around these issues? These are the topics that are investigated in this study.

Before these individual team member analyses can be carried out, a road-map of the ethical considerations that are associated with synthetic biology need to be investigated. Therefore, a literature survey is carried out, exploring the general, "macro" ethical sides of synthetic biology. With this road map, a framework for a questionnaire has been developed, by which the ethical considerations on the individual "micro" level will be analyzed.

Predicted results from practical work

When input and output come together, a bio- thermometer could be created that changes color (or smells differently) at defined temperatures. A possible application of this project (temperature induced color production) can be to produce heat maps of surfaces on a microbial scale. A different application for the temperature sensitivity is to use this system for triggering bi-stable genetic switches or detection of temperature variations in cultivations. Furthermore, we hope the lab results will yield results to confirm or improve mathematical models based on the structure variations introduced in the temperature switch parts.

The modeling part itself could result in a predictive temperature sensitivity algorithm of RNA. Also, it could give insight in the enzymatic reactions that happen in the color pathway.

Finally, the ethics will provide us with a better insight of what iGEM participants know and think of developments in synthetic biology.

References

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IGEM

- ^ J. Lee & N.A. Kotov. Thermometer design at the nanoscale. Nano Today, 2(1):48-51, 2007. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1748-0132(07)70019-1 doi:10.1016/S1748-0132(07)70019-1]

- ^ F. Narberhaus, T. Waldminghaus & S. Chowdhury. RNA thermometers. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 30(1):3-16, 2006. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16438677 PMID:16438677]

- ^ Saheli Chowdhury, Christophe Maris, Frédéric H-T Allain, and Franz Narberhaus. Molecular basis for temperature sensing by an RNA thermometer. The EMBO Journal, 25:2487–2497, 2006. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16710302 PMID:16710302]

- ^ Torsten Waldminghaus, Nadja Heidrich, Sabine Brantl, and Franz Narberhaus. FourU: a novel type of RNA thermometer in Salmonella. Molecular Microbiology, 65(2):413-424, 2007. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17630972 PMID:17630972]

- ^ J . Johansson, P . Mandin, A . Renzoni, C . Chiaruttini, M . Springer, and P . Cossart. An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulance genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell , 110(5):551-561, 2002. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12230973 PMID:12230973]

- ^ V. Martin, D. Pitera, S. Withers, J. Newman and J. Keasling. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nature Biotechnology. 21(7):796-801, 2003. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12778056 PMID:12778056]

- ^ M. Wieland and J.S. Hartig. RNA Quadruplex-Based Modulation of Gene Expression. Chemistry & Biology, 14(7):757–763, 2007. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17656312 PMID:17656312]

- ^ http://mfold.bioinfo.rpi.edu/

- ^ http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at

"

"